Table of Contents

Chapter 19

Conclusion

1

Once the American YMCA gained access to prison camps and established a working relationship with the belligerent

governments through WPA organizations, the Association became instrumental in addressing diplomatic problems related

to war prisoners. Beyond the general treatment of POWs, the two major areas of concern were reprisal facilities and

propaganda camps, which belligerents developed for political objectives. In addition, as the YMCA proved its value in

POW relief operations, a symbiotic relationship grew between the Association and the American Diplomatic Corps. An

indirect result of YMCA WPA operations was the establishment and fostering of informal diplomatic relations between

belligerents during the war.

Once the American YMCA gained access to prison camps and established a working relationship with the belligerent

governments through WPA organizations, the Association became instrumental in addressing diplomatic problems related

to war prisoners. Beyond the general treatment of POWs, the two major areas of concern were reprisal facilities and

propaganda camps, which belligerents developed for political objectives. In addition, as the YMCA proved its value in

POW relief operations, a symbiotic relationship grew between the Association and the American Diplomatic Corps. An

indirect result of YMCA WPA operations was the establishment and fostering of informal diplomatic relations between

belligerents during the war.

2

The general Principle of Reciprocity remained the guiding dictum of Association diplomacy throughout the conflict.

The introduction of new social programs and access to new prison camps usually required reciprocal concessions in

enemy countries. Benefits to enemy prisoners could only be justified in domestic political terms if similar benefits

were to accrue to their nationals held captive by the enemy. Reciprocity required that the International Committee

increase WPA recruitment operations and exponentially increase the WPA budget. By February 1917, sixty-eight American

secretaries were working to provide POW relief services in Europe, including fifteen in Austria-Hungary, thirteen in

Germany, and one in Bulgaria. In addition, American secretaries served in Russia, France, Britain, Italy, and

Romania. Association prisoner relief work promoted a dialogue between the warring nations. Negotiations were

conducted between Britain and Germany in The Hague, and between Germany and Russia in Stockholm and Copenhagen on

a variety of POW issues, including the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, the general treatment of POWs, and

the obligations of neutral nations to interned enemy nationals. The Central Powers and the Allies signed a

number of important agreements before the Armistice to improve general POW conditions. Though American representatives

did not take an active part in these negotiations on an official level, members of the national WPA committees were

key negotiators, and the YMCA benefited from the new opportunities opened by these agreements.1

The general Principle of Reciprocity remained the guiding dictum of Association diplomacy throughout the conflict.

The introduction of new social programs and access to new prison camps usually required reciprocal concessions in

enemy countries. Benefits to enemy prisoners could only be justified in domestic political terms if similar benefits

were to accrue to their nationals held captive by the enemy. Reciprocity required that the International Committee

increase WPA recruitment operations and exponentially increase the WPA budget. By February 1917, sixty-eight American

secretaries were working to provide POW relief services in Europe, including fifteen in Austria-Hungary, thirteen in

Germany, and one in Bulgaria. In addition, American secretaries served in Russia, France, Britain, Italy, and

Romania. Association prisoner relief work promoted a dialogue between the warring nations. Negotiations were

conducted between Britain and Germany in The Hague, and between Germany and Russia in Stockholm and Copenhagen on

a variety of POW issues, including the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, the general treatment of POWs, and

the obligations of neutral nations to interned enemy nationals. The Central Powers and the Allies signed a

number of important agreements before the Armistice to improve general POW conditions. Though American representatives

did not take an active part in these negotiations on an official level, members of the national WPA committees were

key negotiators, and the YMCA benefited from the new opportunities opened by these agreements.1

3

The development of reprisal camps was one of the major atrocities of World War I. Because of the limited options

available to belligerents beyond the battlefield, the punishment of POWs became an attractive method to right a

perceived wrong perpetrated by the enemy or to force the enemy to refrain from the use of some "uncivilized"

weapon or policy. For example, insufficient or inaccurate information about conditions in German prison camps

led the English to prohibit the use of tobacco among German prisoners and reduce German officers' pay in British

prisons, because the Foreign Office believed the Germans had instituted similar policies in their camps. The Germans

retaliated against the British for the use of "hard labor camps," when the British sent German POWs from England

to work on the docks at Le Havre. To protest this act, the Germans sent four times as many British POWs to work in

Libau, in German-occupied Russia. In addition, Archibald Harte argued that the Russians abandoned their practice of

sending their Central Power prisoners to live in Siberian villages and instead adopted large-scale concentration

camps as retaliation against the German practice of incarcerating large numbers of Allied POWs in prison

compounds.2

The development of reprisal camps was one of the major atrocities of World War I. Because of the limited options

available to belligerents beyond the battlefield, the punishment of POWs became an attractive method to right a

perceived wrong perpetrated by the enemy or to force the enemy to refrain from the use of some "uncivilized"

weapon or policy. For example, insufficient or inaccurate information about conditions in German prison camps

led the English to prohibit the use of tobacco among German prisoners and reduce German officers' pay in British

prisons, because the Foreign Office believed the Germans had instituted similar policies in their camps. The Germans

retaliated against the British for the use of "hard labor camps," when the British sent German POWs from England

to work on the docks at Le Havre. To protest this act, the Germans sent four times as many British POWs to work in

Libau, in German-occupied Russia. In addition, Archibald Harte argued that the Russians abandoned their practice of

sending their Central Power prisoners to live in Siberian villages and instead adopted large-scale concentration

camps as retaliation against the German practice of incarcerating large numbers of Allied POWs in prison

compounds.2

4

Belligerents were also capable of using prisoners as hostages to prevent "inhumane" practices. In November 1914,

the Turkish Minister of War warned the American ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, that if England or Greece attacked

any unfortified Turkish towns the "Turks' only reprisal is to detain all English and French subjects." Probably

the most controversial case of prisoner reprisal involved submarine warfare. Winston Churchill, who had been First

Lord of the Admiralty since 1911, announced in 1915 that captured German U-Boat crews would no longer be recognized

as ordinary POWs but were to be considered "pirates" and treated accordingly. The German government retaliated by

seizing thirty-seven British officers, most from prominent British families, and putting them in solitary confinement

in prisons in Cologne, Magdeburg, and Burg.

Belligerents were also capable of using prisoners as hostages to prevent "inhumane" practices. In November 1914,

the Turkish Minister of War warned the American ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, that if England or Greece attacked

any unfortified Turkish towns the "Turks' only reprisal is to detain all English and French subjects." Probably

the most controversial case of prisoner reprisal involved submarine warfare. Winston Churchill, who had been First

Lord of the Admiralty since 1911, announced in 1915 that captured German U-Boat crews would no longer be recognized

as ordinary POWs but were to be considered "pirates" and treated accordingly. The German government retaliated by

seizing thirty-seven British officers, most from prominent British families, and putting them in solitary confinement

in prisons in Cologne, Magdeburg, and Burg.

After Churchill left the Admiralty several months later, his successor reversed the policy, releasing German

submarine crews into the general prison populations. Upon their assurance of the policy's reversal, the Germans

returned the British officers to military prison camps. After the German resumption of unrestricted submarine

warfare in January 1917, the French responded with POW reprisals. After a French hospital ship was torpedoed in

April, the French Navy began carrying German officers on hospital ships as hostages to deter further attacks.

In response, the Germans tripled the number of French POW officers employed on the firing lines of the Western

Front in Arbeitskommandos. The French and Germans eventually recognized that the reprisals had achieved

little, and both sides came to a tacit understanding that these policies should end.3

After Churchill left the Admiralty several months later, his successor reversed the policy, releasing German

submarine crews into the general prison populations. Upon their assurance of the policy's reversal, the Germans

returned the British officers to military prison camps. After the German resumption of unrestricted submarine

warfare in January 1917, the French responded with POW reprisals. After a French hospital ship was torpedoed in

April, the French Navy began carrying German officers on hospital ships as hostages to deter further attacks.

In response, the Germans tripled the number of French POW officers employed on the firing lines of the Western

Front in Arbeitskommandos. The French and Germans eventually recognized that the reprisals had achieved

little, and both sides came to a tacit understanding that these policies should end.3

5

The American YMCA undertook special efforts to prevent reprisals from occurring and offered its good offices to

reverse reprisal measures once they were implemented. The negative side of reciprocity included the reduction of

privileges to POWs if authorities believed the enemy planned to implement a similar reduction in benefits. The

YMCA served as a neutral source of information to confirm or deny planned or implemented punishment for all of

the belligerent nations. If the accusation was unfounded, the Association could preempt the reprisal; if true,

the YMCA worked to redress the original grievance to resecure the withdrawn privileges.

The American YMCA undertook special efforts to prevent reprisals from occurring and offered its good offices to

reverse reprisal measures once they were implemented. The negative side of reciprocity included the reduction of

privileges to POWs if authorities believed the enemy planned to implement a similar reduction in benefits. The

YMCA served as a neutral source of information to confirm or deny planned or implemented punishment for all of

the belligerent nations. If the accusation was unfounded, the Association could preempt the reprisal; if true,

the YMCA worked to redress the original grievance to resecure the withdrawn privileges.

6

American secretaries were able to prevent two serious threats of reprisals during the war. The first represented

a major reversal of YMCA diplomacy, due to the Italian government's delay in constructing Red Triangle huts for

Austro-Hungarian prisoners. In June 1915, the Italians agreed to allow the Association to erect a building in

Ancona, and gave permission for the construction of two additional huts in Avezzano and Padua in December 1916.

In the meantime, the Dual Monarchy permitted the American YMCA to begin relief operations for Italian prisoners

at Mauthausen. Italian procrastination in the construction of the YMCA buildings, due to insufficient funding and

incorrect building permits, forced Austro-Hungarian authorities to threaten to close down Red Triangle operations

for Italian prisoners. Darius A. Davis immediately responded to the crisis by contacting John R. Mott, and the

International Committee cabled $5,000 to finance the project. The Italians issued new permits, and a disaster

was narrowly avoided. Despite the prompt YMCA response, the construction proceeded slowly due to the scarcity

of building material, labor, and transportation, but the Dual Monarchy permitted the YMCA to pursue its programs

for Italian prisoners.4

American secretaries were able to prevent two serious threats of reprisals during the war. The first represented

a major reversal of YMCA diplomacy, due to the Italian government's delay in constructing Red Triangle huts for

Austro-Hungarian prisoners. In June 1915, the Italians agreed to allow the Association to erect a building in

Ancona, and gave permission for the construction of two additional huts in Avezzano and Padua in December 1916.

In the meantime, the Dual Monarchy permitted the American YMCA to begin relief operations for Italian prisoners

at Mauthausen. Italian procrastination in the construction of the YMCA buildings, due to insufficient funding and

incorrect building permits, forced Austro-Hungarian authorities to threaten to close down Red Triangle operations

for Italian prisoners. Darius A. Davis immediately responded to the crisis by contacting John R. Mott, and the

International Committee cabled $5,000 to finance the project. The Italians issued new permits, and a disaster

was narrowly avoided. Despite the prompt YMCA response, the construction proceeded slowly due to the scarcity

of building material, labor, and transportation, but the Dual Monarchy permitted the YMCA to pursue its programs

for Italian prisoners.4

7

The American YMCA played a key role in averting a Franco-German reprisal during the winter of 1916-1917. The

officers' prison camp at Fort Chateauneuf in France had received adverse publicity in Germany. The imperial

government announced that it would establish a reprisal camp in occupied Russia unless conditions improved radically

at Chateauneuf. The Germans demanded that an American embassy official inspect the camp, and Ambassador William

Graves Sharp sent two officials. They concluded their investigation and reported that conditions in Fort Chateauneuf

were excellent. The ranking POW officer also provided a statement to that effect, but added a request for an exercise

and social hall. The French were reluctant to construct a special barrack, but the Germans suggested that they

would cancel their reprisal camp notice if the French made improvements at Chateauneuf. At this point, Ambassador

Sharp officially asked the American YMCA to build a recreation hut in the French prison. The French government

granted immediate permission and offered to pay a portion of the construction costs. In return, the Germans rescinded

their reprisal camp orders.5

The American YMCA played a key role in averting a Franco-German reprisal during the winter of 1916-1917. The

officers' prison camp at Fort Chateauneuf in France had received adverse publicity in Germany. The imperial

government announced that it would establish a reprisal camp in occupied Russia unless conditions improved radically

at Chateauneuf. The Germans demanded that an American embassy official inspect the camp, and Ambassador William

Graves Sharp sent two officials. They concluded their investigation and reported that conditions in Fort Chateauneuf

were excellent. The ranking POW officer also provided a statement to that effect, but added a request for an exercise

and social hall. The French were reluctant to construct a special barrack, but the Germans suggested that they

would cancel their reprisal camp notice if the French made improvements at Chateauneuf. At this point, Ambassador

Sharp officially asked the American YMCA to build a recreation hut in the French prison. The French government

granted immediate permission and offered to pay a portion of the construction costs. In return, the Germans rescinded

their reprisal camp orders.5

8

The polar opposite of reprisal centers were propaganda camps. The YMCA encountered them in Germany, Austria-Hungary,

France, and, to a lesser extent, Russia. The special privileges extended by captors at these camps were designed

to recruit men from dissident minority nationalities, most from subjected colonial peoples, and persuade them to

switch their allegiance in pursuit of the captor's political goals. In the propaganda camps, captors made conditions

as comfortable as possible-they increased rations, loosened regulations, and offered various inducements to win over

prisoners. Many of these subject nationalities were politically sympathetic to their captors' overtures, since the

victory of their imperial masters meant their continued subjugation. Despite these material benefits, POWs in

propaganda camps faced unique problems that the YMCA made a special effort to alleviate.

The polar opposite of reprisal centers were propaganda camps. The YMCA encountered them in Germany, Austria-Hungary,

France, and, to a lesser extent, Russia. The special privileges extended by captors at these camps were designed

to recruit men from dissident minority nationalities, most from subjected colonial peoples, and persuade them to

switch their allegiance in pursuit of the captor's political goals. In the propaganda camps, captors made conditions

as comfortable as possible-they increased rations, loosened regulations, and offered various inducements to win over

prisoners. Many of these subject nationalities were politically sympathetic to their captors' overtures, since the

victory of their imperial masters meant their continued subjugation. Despite these material benefits, POWs in

propaganda camps faced unique problems that the YMCA made a special effort to alleviate.

9

Though the French aimed their regime de faveur at the Alsatians, Danes, and Poles in the German Army,

the primary focus of their propaganda program centered on the Slavic minorities (Polish, Czech, Serbian, Slovak,

Croatian, Dalmatian, and Romanian) of the Austro-Hungarian Army. The key group of these prisoners was made up of

the survivors of the Serbian retreat of December 1915. They were initially evacuated from Corfu to Sardinia, but

most were eventually transported to France to augment the labor force. Once in French hands, they received

special treatment, and the French permitted YMCA secretaries to work freely among them. Many Czechoslovakian and

Polish prisoners rallied to this call, and the French formed national military units which would become the nuclei

of the future Czech and Polish armed forces.

Though the French aimed their regime de faveur at the Alsatians, Danes, and Poles in the German Army,

the primary focus of their propaganda program centered on the Slavic minorities (Polish, Czech, Serbian, Slovak,

Croatian, Dalmatian, and Romanian) of the Austro-Hungarian Army. The key group of these prisoners was made up of

the survivors of the Serbian retreat of December 1915. They were initially evacuated from Corfu to Sardinia, but

most were eventually transported to France to augment the labor force. Once in French hands, they received

special treatment, and the French permitted YMCA secretaries to work freely among them. Many Czechoslovakian and

Polish prisoners rallied to this call, and the French formed national military units which would become the nuclei

of the future Czech and Polish armed forces.

These groups would also play an important role in post-war French foreign policy. The Russians also conducted a

limited propaganda program among the POWs under their control. The Provisional Government primarily recruited Czechoslovak POWs

and organized them into military units to fight against their former Dual Monarchy comrades. The Czech Legion would

later play an important role in the Russian Civil War as one of the few stable military forces in Siberia. The

Russian propaganda program was limited by two factors. First, because the Romanovs had created a polyglot empire with a

large number of subject peoples, the Russians had to limit their propaganda work to nationalities outside of the

tsarist realm. Second, Russian military and economic setbacks prevented the allocation of scarce resources to benefit

special prison populations.6

These groups would also play an important role in post-war French foreign policy. The Russians also conducted a

limited propaganda program among the POWs under their control. The Provisional Government primarily recruited Czechoslovak POWs

and organized them into military units to fight against their former Dual Monarchy comrades. The Czech Legion would

later play an important role in the Russian Civil War as one of the few stable military forces in Siberia. The

Russian propaganda program was limited by two factors. First, because the Romanovs had created a polyglot empire with a

large number of subject peoples, the Russians had to limit their propaganda work to nationalities outside of the

tsarist realm. Second, Russian military and economic setbacks prevented the allocation of scarce resources to benefit

special prison populations.6

10

As explained in earlier chapters, the Germans conducted the most extensive political program for POWs during

the war by attempting to enlist forces to promote political disorder behind enemy lines, to augment their allies'

military forces, and to prepare for future political domination through the formation of proxy forces in Eastern

Europe.

As explained in earlier chapters, the Germans conducted the most extensive political program for POWs during

the war by attempting to enlist forces to promote political disorder behind enemy lines, to augment their allies'

military forces, and to prepare for future political domination through the formation of proxy forces in Eastern

Europe.

To arouse nationalist sentiments in the Allied camp, the Germans focused their political indoctrination efforts

on Irish prisoners at Limburg. With the assistance of Sir Roger Casement, the Germans actively recruited Irish

volunteers to participate in the Easter Rebellion of 1916, but achieved limited success and attracted only a small

force of defectors who were willing to fight for Irish independence.

To arouse nationalist sentiments in the Allied camp, the Germans focused their political indoctrination efforts

on Irish prisoners at Limburg. With the assistance of Sir Roger Casement, the Germans actively recruited Irish

volunteers to participate in the Easter Rebellion of 1916, but achieved limited success and attracted only a small

force of defectors who were willing to fight for Irish independence.

The Germans were far more successful in recruiting British and French colonial troops (Indian Hindus, Asians, and

especially Muslims) for military service. Muslim prisoners (French North Africans, British Indians, and Russian

Central Asians) were concentrated at Zossen, where the Germans established an intensive propaganda program that included

the construction of an impressive mosque.

The Germans were far more successful in recruiting British and French colonial troops (Indian Hindus, Asians, and

especially Muslims) for military service. Muslim prisoners (French North Africans, British Indians, and Russian

Central Asians) were concentrated at Zossen, where the Germans established an intensive propaganda program that included

the construction of an impressive mosque.

Stressing the religious leadership of the Sultan in Constantinople, it is estimated that as many as fifteen thousand Muslim POWs defected to

serve in the Turkish Army and fought in Palestine, Mesopotamia, and Macedonia. In addition, the Germans concentrated their

propaganda activities among the Ukrainian, ethnic German-Russian, and Belorussian prisoners under their control,

forming them into military units. After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, the Germans

transported these troops to the Ukraine to bolster Germany's political influence in Eastern Europe.7

Stressing the religious leadership of the Sultan in Constantinople, it is estimated that as many as fifteen thousand Muslim POWs defected to

serve in the Turkish Army and fought in Palestine, Mesopotamia, and Macedonia. In addition, the Germans concentrated their

propaganda activities among the Ukrainian, ethnic German-Russian, and Belorussian prisoners under their control,

forming them into military units. After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, the Germans

transported these troops to the Ukraine to bolster Germany's political influence in Eastern Europe.7

11

Despite the superior conditions in propaganda camps, political prisoners suffered in other ways. They were branded

deserters, especially by Austria-Hungary, and were abandoned by their governments. Minority prisoners suffered

persecution as traitors by loyal fellow prisoners and lost access to material and financial support from their

homelands.

Despite the superior conditions in propaganda camps, political prisoners suffered in other ways. They were branded

deserters, especially by Austria-Hungary, and were abandoned by their governments. Minority prisoners suffered

persecution as traitors by loyal fellow prisoners and lost access to material and financial support from their

homelands.

For example, the Dual Monarchy outlawed the exportation of Slavic books to Allied POW camps, which contributed to

the shortage of literature among prisoners. Due to this rejection and neglect, YMCA secretaries made special

efforts to address these prisoners' needs. The Association provided native food supplements for Hindu and Muslim

prisoners in Germany to meet their dietary and religious requirements. Allied commentators later criticized these efforts

as promoting the German propaganda effort.

For example, the Dual Monarchy outlawed the exportation of Slavic books to Allied POW camps, which contributed to

the shortage of literature among prisoners. Due to this rejection and neglect, YMCA secretaries made special

efforts to address these prisoners' needs. The Association provided native food supplements for Hindu and Muslim

prisoners in Germany to meet their dietary and religious requirements. Allied commentators later criticized these efforts

as promoting the German propaganda effort.

The American YMCA and the Wilson Administration

12

The American YMCA and the United States government each became increasingly dependent on the resources of the

other to meet their respective policy objectives during the course of the war. President Woodrow Wilson

supported the YMCA's POW relief program from Mott's first trip to Europe in 1914, and acknowledged that the

work was an important component of American neutrality. American embassy staffs became critical assets in

support of Red Triangle diplomacy. The American ambassadors in Berlin, Vienna, Petrograd, Paris, London,

and Rome opened doors for the "Y" ambassadors, providing access to powerful officials, nobility, and clergy.

Though the YMCA had influential patrons in Europe, the Association's standing was clearly bolstered by

official American support.8

The American YMCA and the United States government each became increasingly dependent on the resources of the

other to meet their respective policy objectives during the course of the war. President Woodrow Wilson

supported the YMCA's POW relief program from Mott's first trip to Europe in 1914, and acknowledged that the

work was an important component of American neutrality. American embassy staffs became critical assets in

support of Red Triangle diplomacy. The American ambassadors in Berlin, Vienna, Petrograd, Paris, London,

and Rome opened doors for the "Y" ambassadors, providing access to powerful officials, nobility, and clergy.

Though the YMCA had influential patrons in Europe, the Association's standing was clearly bolstered by

official American support.8

13

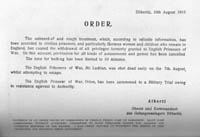

Second, the Wilson Administration assisted the YMCA by providing access to government communications channels

and intelligence. When the British disrupted business cables, secretaries maintained contact with New York

through American consulates. In addition, U.S. diplomats passed political information to secretaries in the

field. American secretaries were neutrals working in countries at war, and a sudden turn in political events

could result in their internment as enemy aliens. When the United States broke off diplomatic relations with

Germany on 7 February 1917, the American embassy arranged for American secretaries to leave on the ambassador's

special train. The embassy kept Conrad Hoffman fully informed about unfolding developments, allowing the Red

Triangle workers to conduct an orderly evacuation from Germany. Finally, the American government provided

financial support and material assistance for YMCA relief operations. The embassy in Constantinople rented

storage space for provisions destined for Allied POWs in Asia Minor, and the American government dispatched

food relief trains to Siberia for starving Central Power POWs through YMCA distribution systems.9

Second, the Wilson Administration assisted the YMCA by providing access to government communications channels

and intelligence. When the British disrupted business cables, secretaries maintained contact with New York

through American consulates. In addition, U.S. diplomats passed political information to secretaries in the

field. American secretaries were neutrals working in countries at war, and a sudden turn in political events

could result in their internment as enemy aliens. When the United States broke off diplomatic relations with

Germany on 7 February 1917, the American embassy arranged for American secretaries to leave on the ambassador's

special train. The embassy kept Conrad Hoffman fully informed about unfolding developments, allowing the Red

Triangle workers to conduct an orderly evacuation from Germany. Finally, the American government provided

financial support and material assistance for YMCA relief operations. The embassy in Constantinople rented

storage space for provisions destined for Allied POWs in Asia Minor, and the American government dispatched

food relief trains to Siberia for starving Central Power POWs through YMCA distribution systems.9

14

On the other hand, the American YMCA provided invaluable assistance to the U.S. government through its WPA

relief efforts. As a neutral power representing the interests of several belligerents, the United States was

legally bound under the Hague Conventions to provide assistance to war prisoners. Due to the government's

limited experience in welfare operations, and an overload of diplomatic priorities, the American Diplomatic

Corps was taxed to the limit. Red Triangle secretaries provided American officials with accurate reports on

camp conditions and the location of prisoners. Association visitations reduced the need for embassy officials

to leave their posts, and the wide range of YMCA operations provided the government with reports from camps that

were generally inaccessible to American officials. But Red Triangle secretaries did work in an unofficial capacity

as neutral welfare workers; although secretaries included political and social observations about their assigned

areas, their reports did not reflect "intelligence collection" activities for the U.S. government. Copies of

reports were also sent to the national WPA committees, the Foreign Office, and the International Committee in

New York.

On the other hand, the American YMCA provided invaluable assistance to the U.S. government through its WPA

relief efforts. As a neutral power representing the interests of several belligerents, the United States was

legally bound under the Hague Conventions to provide assistance to war prisoners. Due to the government's

limited experience in welfare operations, and an overload of diplomatic priorities, the American Diplomatic

Corps was taxed to the limit. Red Triangle secretaries provided American officials with accurate reports on

camp conditions and the location of prisoners. Association visitations reduced the need for embassy officials

to leave their posts, and the wide range of YMCA operations provided the government with reports from camps that

were generally inaccessible to American officials. But Red Triangle secretaries did work in an unofficial capacity

as neutral welfare workers; although secretaries included political and social observations about their assigned

areas, their reports did not reflect "intelligence collection" activities for the U.S. government. Copies of

reports were also sent to the national WPA committees, the Foreign Office, and the International Committee in

New York.

15

In addition, although the primary mission of the American YMCA did not include providing foodstuffs and medical

supplies to POWs, the well-developed infrastructure of the Association in Central and Eastern Europe made the

YMCA the only neutral welfare organization able to provide such aid. Due to the nature of the Association's work,

Red Triangle secretaries were the only Americans located deep inside belligerent territory, and they became the

logical distributors of American aid. As social and economic conditions deteriorated in Russia in the winter of

1916-1917, the American embassy sent trainloads of food and medicine to POWs in Eastern Siberia. The American

YMCA provided the facilities and personnel to distribute this aid to those prisoners in the greatest need.

In addition, although the primary mission of the American YMCA did not include providing foodstuffs and medical

supplies to POWs, the well-developed infrastructure of the Association in Central and Eastern Europe made the

YMCA the only neutral welfare organization able to provide such aid. Due to the nature of the Association's work,

Red Triangle secretaries were the only Americans located deep inside belligerent territory, and they became the

logical distributors of American aid. As social and economic conditions deteriorated in Russia in the winter of

1916-1917, the American embassy sent trainloads of food and medicine to POWs in Eastern Siberia. The American

YMCA provided the facilities and personnel to distribute this aid to those prisoners in the greatest need.

The Allied blockade created famine conditions in Central Europe, which had a tremendous impact on Allied prisoners.

The YMCA provided an important distribution network for food parcels from neutral countries and a chief source of

financial remittance to prisoners. The food situation had become so desperate by January 1917 that the American

YMCA, the American Red Cross, and the Rockefeller Commission agreed to set up the Council of Prisoners of War,

with the full approval of the U.S. State Department. This organization was to provide POWs with food, clothing,

and medicine to supplement their meager daily rations and help them survive their imprisonment. Planning

proceeded to the point where the German government accepted all of the British conditions to begin the service,

and shipping and distribution plans through neutral ports had been finalized. The relief plan, however,

collapsed when the British finally decided to enforce a strict blockade to force the Germans to surrender, even

though this meant starvation for Allied prisoners as well.10

The Allied blockade created famine conditions in Central Europe, which had a tremendous impact on Allied prisoners.

The YMCA provided an important distribution network for food parcels from neutral countries and a chief source of

financial remittance to prisoners. The food situation had become so desperate by January 1917 that the American

YMCA, the American Red Cross, and the Rockefeller Commission agreed to set up the Council of Prisoners of War,

with the full approval of the U.S. State Department. This organization was to provide POWs with food, clothing,

and medicine to supplement their meager daily rations and help them survive their imprisonment. Planning

proceeded to the point where the German government accepted all of the British conditions to begin the service,

and shipping and distribution plans through neutral ports had been finalized. The relief plan, however,

collapsed when the British finally decided to enforce a strict blockade to force the Germans to surrender, even

though this meant starvation for Allied prisoners as well.10

16

Even after the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, the American YMCA maintained a presence

in the German Empire in the person of Conrad Hoffman. He made the relief of American prisoners a priority, and

helped U.S. POWs avoid many of the problems that plagued other Allied prisoners. Hoffman experienced at first hand

life in Germany during the last years of the war and after the Armistice, and he was an important source of

expertise for the Allied High Commission.

Even after the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, the American YMCA maintained a presence

in the German Empire in the person of Conrad Hoffman. He made the relief of American prisoners a priority, and

helped U.S. POWs avoid many of the problems that plagued other Allied prisoners. Hoffman experienced at first hand

life in Germany during the last years of the war and after the Armistice, and he was an important source of

expertise for the Allied High Commission.

He was able to rapidly set up relief operations for Allied prisoners once he regained access to plentiful

supplies. After the American YMCA reestablished its presence in German prison camps, the Association performed

another important service in support of Wilson's foreign policy by fighting Bolshevik propaganda in an ideological

war for the hearts and minds of Russian prisoners. The YMCA challenged Red agitators through the Association's

"Four-fold Program." When it became clear that the Bolsheviks would triumph in the Russian Civil War, the American

YMCA continued the struggle by supporting Russian émigrés and the Russian Orthodox Church.

He was able to rapidly set up relief operations for Allied prisoners once he regained access to plentiful

supplies. After the American YMCA reestablished its presence in German prison camps, the Association performed

another important service in support of Wilson's foreign policy by fighting Bolshevik propaganda in an ideological

war for the hearts and minds of Russian prisoners. The YMCA challenged Red agitators through the Association's

"Four-fold Program." When it became clear that the Bolsheviks would triumph in the Russian Civil War, the American

YMCA continued the struggle by supporting Russian émigrés and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Diplomatic Obstacles

17

While American YMCA "ambassadors" achieved notable victories during their negotiations, difficult barriers

undermined their overall effectiveness. The most serious obstacle was the high level of suspicion created by

the pressures of total warfare. Whereas the Association's assistance had generally been welcomed in earlier

wars, such as the Russo-Japanese War, YMCA representatives met deep distrust regarding their motives. Suspicions

were bred by propaganda campaigns launched by the belligerents to stir their populations to arms and to justify

the righteousness of their causes. The Association encountered this suspicion in four major forms.

While American YMCA "ambassadors" achieved notable victories during their negotiations, difficult barriers

undermined their overall effectiveness. The most serious obstacle was the high level of suspicion created by

the pressures of total warfare. Whereas the Association's assistance had generally been welcomed in earlier

wars, such as the Russo-Japanese War, YMCA representatives met deep distrust regarding their motives. Suspicions

were bred by propaganda campaigns launched by the belligerents to stir their populations to arms and to justify

the righteousness of their causes. The Association encountered this suspicion in four major forms.

18

First was the fear that American secretaries were enemy agents. Some governments were sensitive about YMCA

representatives' surnames. Secretaries with German family names could not be assigned to Britain or Russia

because military authorities questioned their allegiance. Behind the barbed wire, prisoners were equally

skeptical of American secretaries as potential propaganda agents working on behalf of the enemy. Secretaries

reported that they found it difficult to win the confidence of both guards and captives, which was an essential

first step for social work. Proselytizing was another major source of suspicion, especially in countries where

the YMCA did not already have a strong organization. Some governments questioned the Association's Protestant

foundations, and conservative social elements, especially the clergy, feared Protestant penetration and "contamination."

The American YMCA's guiding principle of promoting the prisoner's own faith instead of spiritual conversion was

not readily accepted by all foreigners. Secretaries had to work hard to overcome suspicions in Orthodox, Catholic,

and Muslim countries to alleviate distrust. Once secretaries set up POW services and the local clergy inspected

the Red Triangle operations, the Association's efforts were almost always praised.11

First was the fear that American secretaries were enemy agents. Some governments were sensitive about YMCA

representatives' surnames. Secretaries with German family names could not be assigned to Britain or Russia

because military authorities questioned their allegiance. Behind the barbed wire, prisoners were equally

skeptical of American secretaries as potential propaganda agents working on behalf of the enemy. Secretaries

reported that they found it difficult to win the confidence of both guards and captives, which was an essential

first step for social work. Proselytizing was another major source of suspicion, especially in countries where

the YMCA did not already have a strong organization. Some governments questioned the Association's Protestant

foundations, and conservative social elements, especially the clergy, feared Protestant penetration and "contamination."

The American YMCA's guiding principle of promoting the prisoner's own faith instead of spiritual conversion was

not readily accepted by all foreigners. Secretaries had to work hard to overcome suspicions in Orthodox, Catholic,

and Muslim countries to alleviate distrust. Once secretaries set up POW services and the local clergy inspected

the Red Triangle operations, the Association's efforts were almost always praised.11

19

The general lack of secretaries was a second major barrier to YMCA WPA service. One of Carlisle V. Hibbard's

primary functions after his return to New York was to recruit eligible men for POW relief services. In a

letter to Edward T. Heald from June 1916, Hibbard outlined the necessary qualifications for a WPA field secretary.

The successful applicants must be "first and foremost … men of strong Christian character, of tactful,

genial personality, and of strong optimism." The emphasis on optimism is an interesting criterion, since it

explains the positive and constructive reports that secretaries made after prison camp inspections.

The general lack of secretaries was a second major barrier to YMCA WPA service. One of Carlisle V. Hibbard's

primary functions after his return to New York was to recruit eligible men for POW relief services. In a

letter to Edward T. Heald from June 1916, Hibbard outlined the necessary qualifications for a WPA field secretary.

The successful applicants must be "first and foremost … men of strong Christian character, of tactful,

genial personality, and of strong optimism." The emphasis on optimism is an interesting criterion, since it

explains the positive and constructive reports that secretaries made after prison camp inspections.

Though post-war critics charged Association secretaries with having "bought" their access to prison camps by

filing favorable reports, these secretaries were probably faithfully recording their "optimistic" impressions

of dismal situations. In addition, Hibbard insisted that the potential secretary must "have a knowledge of

European languages." The multi-lingual requirement restricted the pool of potential candidates. Americans that

met all of these requirements were either college-educated (a limited pool) or were immigrants (possibly

unacceptable to belligerent governments). For secretaries to be effective, they had to speak the language

of the captors, so that they could communicate with guards and prison administrators, as well as the language(s)

of the prison camp inmates.12

Though post-war critics charged Association secretaries with having "bought" their access to prison camps by

filing favorable reports, these secretaries were probably faithfully recording their "optimistic" impressions

of dismal situations. In addition, Hibbard insisted that the potential secretary must "have a knowledge of

European languages." The multi-lingual requirement restricted the pool of potential candidates. Americans that

met all of these requirements were either college-educated (a limited pool) or were immigrants (possibly

unacceptable to belligerent governments). For secretaries to be effective, they had to speak the language

of the captors, so that they could communicate with guards and prison administrators, as well as the language(s)

of the prison camp inmates.12

20

Scarce resources were a third barrier to Association assistance to war prisoners. Though finances were rarely a problem, due to John R. Mott's

extraordinary fund-raising capability, many basic necessities were extremely difficult

to procure. The demand for foreign language books, especially in the Slavic languages of the Dual Monarchy, always

outstripped the short supply. The Austro-Hungarian export ban restricted publication supplies, but even when the

YMCA did manage to obtain books, it was difficult to send large numbers through the censors. At the other extreme,

the YMCA encountered problems finding Russian primers to teach the large numbers of illiterate Russian prisoners.

Scarce resources were a third barrier to Association assistance to war prisoners. Though finances were rarely a problem, due to John R. Mott's

extraordinary fund-raising capability, many basic necessities were extremely difficult

to procure. The demand for foreign language books, especially in the Slavic languages of the Dual Monarchy, always

outstripped the short supply. The Austro-Hungarian export ban restricted publication supplies, but even when the

YMCA did manage to obtain books, it was difficult to send large numbers through the censors. At the other extreme,

the YMCA encountered problems finding Russian primers to teach the large numbers of illiterate Russian prisoners.

Religious articles also became a challenge. Hoffman went to extremes to obtain antimensa (consecrated altar cloths)

so that Orthodox religious services could be conducted in German prison camps. As the war dragged on, the shortage

of basic foodstuffs and medical supplies also undermined the Association's POW program. The deteriorating condition

of a large number of prisoners in Central and Europe forced the YMCA to concentrate on simply keeping POWs

alive. The effectiveness of the Allied blockade and the West's inability to supply Russia resulted in insufficient

food rations for war prisoners. Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners suffered the most, since they were unlikely

to receive food parcels from home to supplement their meager diets. The Allied decision to deny the Council of

Prisoners of War permission to institute a food distribution program placed an even greater burden on war

prisoners.13

Religious articles also became a challenge. Hoffman went to extremes to obtain antimensa (consecrated altar cloths)

so that Orthodox religious services could be conducted in German prison camps. As the war dragged on, the shortage

of basic foodstuffs and medical supplies also undermined the Association's POW program. The deteriorating condition

of a large number of prisoners in Central and Europe forced the YMCA to concentrate on simply keeping POWs

alive. The effectiveness of the Allied blockade and the West's inability to supply Russia resulted in insufficient

food rations for war prisoners. Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners suffered the most, since they were unlikely

to receive food parcels from home to supplement their meager diets. The Allied decision to deny the Council of

Prisoners of War permission to institute a food distribution program placed an even greater burden on war

prisoners.13

21

Regional and administrative bureaucracy also constrained effective YMCA WPA service. Though national governments

may have approved Association access to prison camps or agreed to the introduction of new programs, bureaucratic

obstacles at lower levels sometimes delayed implementation. In France, the YMCA never gained access to Central

Power civilian internees because the Ministry of the Interior refused to grant the Association permission to visit

the camps under their administrative control. In Germany, once the imperial Ministry of War agreed to accept YMCA

work, Harte needed additional permission from the regional Army Corps commanders and sometimes from one of three

royal war ministries (Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg). Even Britain was subject to local governmental

peculiarities. The German civilians interned on the Isle of Man did not receive Association services because the

local government, long invested with special rights by the Crown, refused to admit American secretaries to inspect

the internment camp at Knockaloe. The Friends' War Emergency Committee had to undertake relief operations for these

prisoners.14

Regional and administrative bureaucracy also constrained effective YMCA WPA service. Though national governments

may have approved Association access to prison camps or agreed to the introduction of new programs, bureaucratic

obstacles at lower levels sometimes delayed implementation. In France, the YMCA never gained access to Central

Power civilian internees because the Ministry of the Interior refused to grant the Association permission to visit

the camps under their administrative control. In Germany, once the imperial Ministry of War agreed to accept YMCA

work, Harte needed additional permission from the regional Army Corps commanders and sometimes from one of three

royal war ministries (Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg). Even Britain was subject to local governmental

peculiarities. The German civilians interned on the Isle of Man did not receive Association services because the

local government, long invested with special rights by the Crown, refused to admit American secretaries to inspect

the internment camp at Knockaloe. The Friends' War Emergency Committee had to undertake relief operations for these

prisoners.14

Conclusion

22

Did the American YMCA succeed in its three objectives of alleviating the suffering of the millions of "forgotten

men" in POW camps, bolstering American foreign policy, and preparing the ground for new mission fields after the

war? The final balance sheet is mixed, especially in terms of POW relief. On one side of the ledger, the reputation

of the Association's POW program suffered as it became the target of serious criticism after the war. The actual

effect of the YMCA on prisoner welfare in absolute numbers suggests a minimal impact. The Association's services

reached a small percentage of the prisoners during the war. At the peak of operations in February 1917, the American

YMCA had a total of sixty-eight secretaries serving over six million prisoners. In Germany and Austria-Hungary alone,

a total of twenty-five American secretaries administered aid to over four million Allied war prisoners. The suffering

of prisoners of the Great War may have been too great a challenge, especially for just one social welfare

organization.15

Did the American YMCA succeed in its three objectives of alleviating the suffering of the millions of "forgotten

men" in POW camps, bolstering American foreign policy, and preparing the ground for new mission fields after the

war? The final balance sheet is mixed, especially in terms of POW relief. On one side of the ledger, the reputation

of the Association's POW program suffered as it became the target of serious criticism after the war. The actual

effect of the YMCA on prisoner welfare in absolute numbers suggests a minimal impact. The Association's services

reached a small percentage of the prisoners during the war. At the peak of operations in February 1917, the American

YMCA had a total of sixty-eight secretaries serving over six million prisoners. In Germany and Austria-Hungary alone,

a total of twenty-five American secretaries administered aid to over four million Allied war prisoners. The suffering

of prisoners of the Great War may have been too great a challenge, especially for just one social welfare

organization.15

23

The WPA work of the American YMCA also led to serious tensions within the international Association community.

Tensions emerged between the International Committee, the German National YMCA Council, and the World's Alliance.

Although Christian Phildius and the World's Committee were the titular leaders of war prisoner relief work, their

authority became increasingly nominal during the war. There was an advantage in having the Geneva organization

rule on important decisions, because this committee enjoyed international support as the pre-war leader of the

global Association Movement. The World's Alliance lacked the financial and manpower resources, however, to play

a leading role in POW relief. Phildius' diplomatic efforts achieved only modest success in Bulgaria and Turkey.

The driving force behind POW relief was Mott's financial wizardry and Harte's astute shuttle diplomacy. The

American YMCA's relief program was also bolstered by the political support of the Wilson Administration.

The WPA work of the American YMCA also led to serious tensions within the international Association community.

Tensions emerged between the International Committee, the German National YMCA Council, and the World's Alliance.

Although Christian Phildius and the World's Committee were the titular leaders of war prisoner relief work, their

authority became increasingly nominal during the war. There was an advantage in having the Geneva organization

rule on important decisions, because this committee enjoyed international support as the pre-war leader of the

global Association Movement. The World's Alliance lacked the financial and manpower resources, however, to play

a leading role in POW relief. Phildius' diplomatic efforts achieved only modest success in Bulgaria and Turkey.

The driving force behind POW relief was Mott's financial wizardry and Harte's astute shuttle diplomacy. The

American YMCA's relief program was also bolstered by the political support of the Wilson Administration.

24

The tension between the International Committee and the World's Committee led to a struggle for control over

POW relief work between the two organizations. In dealing with the Germans, Phildius attempted to work independently,

while Harte demanded that work should be undertaken under his direction. The World's Committee felt threatened when

Harte responded by opening an American YMCA office in Bern "to increase the efficiency and supervision of WPA work

in Germany." The need to display wartime unity prevented an open break within the YMCA structure. These tensions

with the World's Alliance were resolved to the Americans' satisfaction after the Armistice, when the International

Committee assumed outright responsibility and control over all of the WPA relief missions in Central and Eastern

Europe.16

The tension between the International Committee and the World's Committee led to a struggle for control over

POW relief work between the two organizations. In dealing with the Germans, Phildius attempted to work independently,

while Harte demanded that work should be undertaken under his direction. The World's Committee felt threatened when

Harte responded by opening an American YMCA office in Bern "to increase the efficiency and supervision of WPA work

in Germany." The need to display wartime unity prevented an open break within the YMCA structure. These tensions

with the World's Alliance were resolved to the Americans' satisfaction after the Armistice, when the International

Committee assumed outright responsibility and control over all of the WPA relief missions in Central and Eastern

Europe.16

25

The Association's reputation also suffered criticism due to its support of American neutrality prior to February

1917. In the American YMCA's dealings with the Central Powers, Harte gained access to German prison camps because

the United States was one of the few Great Powers not involved in the conflict. After the Wilson Administration declared

war on Germany, the International Committee decided to throw its full support behind the Allied war effort, instead

of maintaining its neutral policies in support of the American YMCA's original mission. Nationalism emerged as a major

threat to the integrity of the World's Alliance, an organization dedicated to Christian Internationalism. Although

the World's Committee prevented a permanent cleavage in the organization during the August 1918 meetings between Mott

and the German national leadership, a serious rift remained in the World's Alliance for several years after the war.

The Association's reputation also suffered criticism due to its support of American neutrality prior to February

1917. In the American YMCA's dealings with the Central Powers, Harte gained access to German prison camps because

the United States was one of the few Great Powers not involved in the conflict. After the Wilson Administration declared

war on Germany, the International Committee decided to throw its full support behind the Allied war effort, instead

of maintaining its neutral policies in support of the American YMCA's original mission. Nationalism emerged as a major

threat to the integrity of the World's Alliance, an organization dedicated to Christian Internationalism. Although

the World's Committee prevented a permanent cleavage in the organization during the August 1918 meetings between Mott

and the German national leadership, a serious rift remained in the World's Alliance for several years after the war.

26

Within the United States, the Association had to address public relations problems associated with its POW

relief work, especially after the country entered the war. The American YMCA did not stress its assistance to

Central Power POWs during publicity drives. The war had radically changed the Association's fund-raising

operations. At the beginning of the war, Mott relied on the generosity of a very small number of wealthy

philanthropists to underwrite the POW relief program. By 1917, it was clear that donations from a limited

number of wealthy patrons would be insufficient to meet the growing demands for welfare assistance the Association

faced. As a result, the YMCA joined forces with other American social welfare organizations operating overseas

and conducted several fundraising drives, calling for modest subscriptions from across the country. This culminated

in the United War Work Campaign in November 1918, which resulted in a subscription of $203 million, the largest

sum ever collected through volunteer offerings in American history up to that point. The American YMCA received

58.65 percent of this total, or $108.5 million. By this time, the Association was conducting a plethora of social

service programs for American soldiers and sailors at home and overseas, in addition to relief work in the U.S.

and morale work for Allied troops. Only a small percentage of these funds was assigned to WPA relief work. Again,

the YMCA did not publicize its aid to war prisoners because they feared adverse public reaction, which could have

undermined the subscription. Instead, the Association circulated information about the WPA on a "strictly private,

not to be printed" basis through For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms series. Other publications, such as

Items of Interest and Progress, regarding POW relief work in Britain, were issued with Robert L. Ewing's

admonition that "it is unadvisable to give general publicity to the work of the YMCA for prisoners-of-war." The

secrecy surrounding POW work did not improve the Association's overall image during a post-war Senate investigation

surrounding alleged YMCA price gouging on articles sold at U.S. Army canteens.17

Within the United States, the Association had to address public relations problems associated with its POW

relief work, especially after the country entered the war. The American YMCA did not stress its assistance to

Central Power POWs during publicity drives. The war had radically changed the Association's fund-raising

operations. At the beginning of the war, Mott relied on the generosity of a very small number of wealthy

philanthropists to underwrite the POW relief program. By 1917, it was clear that donations from a limited

number of wealthy patrons would be insufficient to meet the growing demands for welfare assistance the Association

faced. As a result, the YMCA joined forces with other American social welfare organizations operating overseas

and conducted several fundraising drives, calling for modest subscriptions from across the country. This culminated

in the United War Work Campaign in November 1918, which resulted in a subscription of $203 million, the largest

sum ever collected through volunteer offerings in American history up to that point. The American YMCA received

58.65 percent of this total, or $108.5 million. By this time, the Association was conducting a plethora of social

service programs for American soldiers and sailors at home and overseas, in addition to relief work in the U.S.

and morale work for Allied troops. Only a small percentage of these funds was assigned to WPA relief work. Again,

the YMCA did not publicize its aid to war prisoners because they feared adverse public reaction, which could have

undermined the subscription. Instead, the Association circulated information about the WPA on a "strictly private,

not to be printed" basis through For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms series. Other publications, such as

Items of Interest and Progress, regarding POW relief work in Britain, were issued with Robert L. Ewing's

admonition that "it is unadvisable to give general publicity to the work of the YMCA for prisoners-of-war." The

secrecy surrounding POW work did not improve the Association's overall image during a post-war Senate investigation

surrounding alleged YMCA price gouging on articles sold at U.S. Army canteens.17

27

In supporting Wilsonian foreign policy, the American YMCA had a checkered record. To gain access to belligerent

prison camps, secretaries introduced war work for Allied and Central Power soldiers to demonstrate the benefits of the Association

program and to gain the trust of foreign governments. This service in support of belligerent troops before the United

States entered the war clearly violated American neutrality and led to considerable criticism of the American YMCA

in Germany. Davis' attempts to improve his standing with the French and Italian governments by supporting the work

of the Foyers du Soldat and the Casa del Soldato eventually led to YMCA access to prison camps in

both countries.

In supporting Wilsonian foreign policy, the American YMCA had a checkered record. To gain access to belligerent

prison camps, secretaries introduced war work for Allied and Central Power soldiers to demonstrate the benefits of the Association

program and to gain the trust of foreign governments. This service in support of belligerent troops before the United

States entered the war clearly violated American neutrality and led to considerable criticism of the American YMCA

in Germany. Davis' attempts to improve his standing with the French and Italian governments by supporting the work

of the Foyers du Soldat and the Casa del Soldato eventually led to YMCA access to prison camps in

both countries.

In response, the Germans accused the Americans of duplicity, since the YMCA promoted itself as a neutral,

Christian social welfare organization. This criticism was leveled mainly at Mott through the press and led to

a protest declaration that withdrew German recognition of Mott as chairman of the Continuation Committee of

the World Missionary Conference. The YMCA's gradual shift away from neutrality, however, corresponded to the

American government's relaxation of neutrality regulations regarding the sale of munitions and the extension

of loans to belligerent nations, especially the Allies.18

In response, the Germans accused the Americans of duplicity, since the YMCA promoted itself as a neutral,

Christian social welfare organization. This criticism was leveled mainly at Mott through the press and led to

a protest declaration that withdrew German recognition of Mott as chairman of the Continuation Committee of

the World Missionary Conference. The YMCA's gradual shift away from neutrality, however, corresponded to the

American government's relaxation of neutrality regulations regarding the sale of munitions and the extension

of loans to belligerent nations, especially the Allies.18

28

The American YMCA's efforts to combat Bolshevism in German prison camps after the Armistice also met with

limited success. While the Association countered Bolshevik propaganda, too many factors undermined the

YMCA's program. First, the Allies failed to develop a coherent, coordinated policy to deal with Bolsheviks.

Instead, a fragmented and inconsistent policy added to the chaotic conditions in Russia. Second, the Bolshevik

triumph in the Russian Civil War eliminated any gains the Association had achieved in Germany. For most prisoners,

isolated in Central Power prison camps for years, the civil war in Russia was beyond their comprehension. Their

goal was simply to return home and renew life again outside of the barbed-wire stockades. That their homeland was

undergoing the terrible strains of a social revolution was impossible to care about or even understand. Joining

the White Russian armies or fighting with the Red Army had little appeal for many prisoners. While the French had

hopes of recruiting Russian prisoners for the White Russian cause, the American YMCA did little to promote this goal.

The American YMCA's efforts to combat Bolshevism in German prison camps after the Armistice also met with

limited success. While the Association countered Bolshevik propaganda, too many factors undermined the

YMCA's program. First, the Allies failed to develop a coherent, coordinated policy to deal with Bolsheviks.

Instead, a fragmented and inconsistent policy added to the chaotic conditions in Russia. Second, the Bolshevik

triumph in the Russian Civil War eliminated any gains the Association had achieved in Germany. For most prisoners,

isolated in Central Power prison camps for years, the civil war in Russia was beyond their comprehension. Their

goal was simply to return home and renew life again outside of the barbed-wire stockades. That their homeland was

undergoing the terrible strains of a social revolution was impossible to care about or even understand. Joining

the White Russian armies or fighting with the Red Army had little appeal for many prisoners. While the French had

hopes of recruiting Russian prisoners for the White Russian cause, the American YMCA did little to promote this goal.

29

On the positive side, the American YMCA's accomplishments far outweighed these comparatively minor drawbacks.

Where the American YMCA did establish WPA programs, they were able to greatly improve the general welfare of

the prisoners. Harte's diplomatic missions were an impressive success, especially in light of the wartime

conditions he faced. He managed to gain access and expand operations in most of the belligerent nations, and the

American YMCA eventually established POW relief work across Europe, North Africa, India, Siberia, Japan,

Canada, and the United States. This was no mean accomplishment, considering the deep suspicion these nations

exhibited towards neutral welfare organizations, especially those requesting permission to aid the enemy

within their borders.

On the positive side, the American YMCA's accomplishments far outweighed these comparatively minor drawbacks.

Where the American YMCA did establish WPA programs, they were able to greatly improve the general welfare of

the prisoners. Harte's diplomatic missions were an impressive success, especially in light of the wartime

conditions he faced. He managed to gain access and expand operations in most of the belligerent nations, and the

American YMCA eventually established POW relief work across Europe, North Africa, India, Siberia, Japan,

Canada, and the United States. This was no mean accomplishment, considering the deep suspicion these nations

exhibited towards neutral welfare organizations, especially those requesting permission to aid the enemy

within their borders.

30

In spite of the small number of secretaries sent to Central Europe, American Red Triangle workers still helped

a tremendous number of prisoners who had no other source of solace. World War I was the first total war fought

on a global scale. None of the belligerents were adequately prepared to handle the unanticipated POW burden

they carried, which increased steadily as the war progressed. The size of the American secretarial force must

also be considered in terms of the Principle of Visitation. By forming Associations within prison camps, with

POWs providing the manpower for social services, a single secretary could establish the foundation for extensive

welfare services over a large area. The YMCA provided the initial equipment and supplies, and with a little

organization and training, the prisoners could conduct self-help operations. The prison camps that the secretaries

visited and set up operations in also tended to be the largest prison facilities in their respective countries.

While secretaries served a modest number of prison camps, a large percentage of prisoners overall received Red

Triangle benefits. In addition, a "trickle-down effect" occurred as a result of prisoner transfers between

camps. POWs imbued with the YMCA spirit occasionally worked independently to set up Associations in new camps

without the assistance of a Red Triangle secretary. To support the WPA program, the International Committee

steadily increased its financial commitment in support of POW relief. During 1914, the American YMCA expended

only $23,000 for war prisoner relief; by November 1919, this contribution had increased to $2.8 million.19

In spite of the small number of secretaries sent to Central Europe, American Red Triangle workers still helped

a tremendous number of prisoners who had no other source of solace. World War I was the first total war fought

on a global scale. None of the belligerents were adequately prepared to handle the unanticipated POW burden

they carried, which increased steadily as the war progressed. The size of the American secretarial force must

also be considered in terms of the Principle of Visitation. By forming Associations within prison camps, with

POWs providing the manpower for social services, a single secretary could establish the foundation for extensive

welfare services over a large area. The YMCA provided the initial equipment and supplies, and with a little

organization and training, the prisoners could conduct self-help operations. The prison camps that the secretaries

visited and set up operations in also tended to be the largest prison facilities in their respective countries.

While secretaries served a modest number of prison camps, a large percentage of prisoners overall received Red

Triangle benefits. In addition, a "trickle-down effect" occurred as a result of prisoner transfers between

camps. POWs imbued with the YMCA spirit occasionally worked independently to set up Associations in new camps

without the assistance of a Red Triangle secretary. To support the WPA program, the International Committee

steadily increased its financial commitment in support of POW relief. During 1914, the American YMCA expended

only $23,000 for war prisoner relief; by November 1919, this contribution had increased to $2.8 million.19

31

The American YMCA should be considered a pioneer in international social work, since general relief for POWs had

never been conducted on so grand a scale. American secretaries provided essential services to prisoners in

transferring funds, mail, and parcels and distributing private, neutral charitable aid. The Association was a

neutral source of information regarding conditions in prison camps, and it relieved U.S. embassy staffs of many

administrative burdens. The organization also served as an important relief distribution agency for the U.S.

government, especially in Russia, where no other infrastructure existed. As the leading partner in the Council of

Prisoners of War, the YMCA might have effectively reduced the suffering of war prisoners in Central and Eastern

Europe if the Allies had approved the project. Without question, the American YMCA provided essential services to

POWs in Europe, ranging from simply providing a diversion from prison camp monotony to saving lives by closing down

reprisal camps and promoting food distribution.

The American YMCA should be considered a pioneer in international social work, since general relief for POWs had

never been conducted on so grand a scale. American secretaries provided essential services to prisoners in

transferring funds, mail, and parcels and distributing private, neutral charitable aid. The Association was a

neutral source of information regarding conditions in prison camps, and it relieved U.S. embassy staffs of many

administrative burdens. The organization also served as an important relief distribution agency for the U.S.

government, especially in Russia, where no other infrastructure existed. As the leading partner in the Council of

Prisoners of War, the YMCA might have effectively reduced the suffering of war prisoners in Central and Eastern

Europe if the Allies had approved the project. Without question, the American YMCA provided essential services to

POWs in Europe, ranging from simply providing a diversion from prison camp monotony to saving lives by closing down

reprisal camps and promoting food distribution.

32

In addition, the YMCA, through its POW relief services, gained access to new mission fields and helped the