Table of Contents

Chapter 1

"Evangelizing the World in a Generation": The YMCA Movement around the World before the First World War

1

The development of YMCA movements in the Central Power empires (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire) is

crucial to understanding the influence of the YMCA at the beginning of World War I and the organization's future role in providing

relief services to Allied prisoners of war. These four nations reflected the fundamental challenges facing the North American

Association in its global evangelization mission. Germany was a Protestant nation that developed a strong Association movement

during the nineteenth century. As the world's leading Roman Catholic empire, Austria-Hungary was far more resistant to the

establishment and growth of the YMCA within its borders. Bulgaria was even more resistant because of its Orthodox composition.

The Association's greatest challenge, however, was the Ottoman Empire, because Turkey was the great power of the Muslim world.

Despite these varying degrees of support and resistance, John R. Mott and the American YMCA rose to meet these challenges and

focused their energy on establishing and expanding Association influence in Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim countries during the

pre-war years. Before addressing the growth of the Association movement in the Central Power nations, it is important to review

the genesis and raison d'Ítre of the Young Men's Christian Association, and its development in the United States.

The development of YMCA movements in the Central Power empires (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire) is

crucial to understanding the influence of the YMCA at the beginning of World War I and the organization's future role in providing

relief services to Allied prisoners of war. These four nations reflected the fundamental challenges facing the North American

Association in its global evangelization mission. Germany was a Protestant nation that developed a strong Association movement

during the nineteenth century. As the world's leading Roman Catholic empire, Austria-Hungary was far more resistant to the

establishment and growth of the YMCA within its borders. Bulgaria was even more resistant because of its Orthodox composition.

The Association's greatest challenge, however, was the Ottoman Empire, because Turkey was the great power of the Muslim world.

Despite these varying degrees of support and resistance, John R. Mott and the American YMCA rose to meet these challenges and

focused their energy on establishing and expanding Association influence in Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim countries during the

pre-war years. Before addressing the growth of the Association movement in the Central Power nations, it is important to review

the genesis and raison d'Ítre of the Young Men's Christian Association, and its development in the United States.

2

The Young Men's Christian Association movement officially began on 6 June 1844, when George Williams organized the first

Association in London. Williams was stirred by the writings of the American revivalist Charles Grandison Finney, and the

YMCA was a direct outgrowth of the Second Great Awakening of the mid-nineteenth century in the U.S. The first organization

consisted of twelve clerks from drapery and dry goods stores who sought Christian fellowship and refuge from the moral evils

of urban life. The YMCA arose in response to the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution, as many young men left their

rural homes to find employment in urban centers.

The Young Men's Christian Association movement officially began on 6 June 1844, when George Williams organized the first

Association in London. Williams was stirred by the writings of the American revivalist Charles Grandison Finney, and the

YMCA was a direct outgrowth of the Second Great Awakening of the mid-nineteenth century in the U.S. The first organization

consisted of twelve clerks from drapery and dry goods stores who sought Christian fellowship and refuge from the moral evils

of urban life. The YMCA arose in response to the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution, as many young men left their

rural homes to find employment in urban centers.

Cut off from their traditional ties to family, community, and church, these men faced many temptations in city life,

including alcohol, prostitution, and other vices. The YMCA offered young men a Christian alternative by providing libraries

filled with wholesome books and newspapers, offering weekly Bible classes, and encouraging men to assist in Sunday Schools

and missions. The Association movement was a Protestant effort from the very beginning, with charter members from the Church

of England, Methodist, Congregational, and Baptist churches.1

Cut off from their traditional ties to family, community, and church, these men faced many temptations in city life,

including alcohol, prostitution, and other vices. The YMCA offered young men a Christian alternative by providing libraries

filled with wholesome books and newspapers, offering weekly Bible classes, and encouraging men to assist in Sunday Schools

and missions. The Association movement was a Protestant effort from the very beginning, with charter members from the Church

of England, Methodist, Congregational, and Baptist churches.1

3 The YMCA became a global movement as a direct result of the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851. The English Association set up a booth at the exposition, and foreign visitors came into contact with the YMCA for the first time. Impressed, many of these visitors returned to the United States and Canada determined to organize similar organizations in their cities. The first YMCA in North America opened in Montreal in November 1851, and the second followed a month later in Boston. The phenomenon spread quickly across the continent over the next few years. In 1854, delegates from twenty-two Associations in the U.S. and British Provinces (Canada) met in Buffalo and formed a confederation of "independent, equal, but co-operating Associations." The representatives agreed to meet at an annual convention and to organize a central executive committee to provide leadership for the organization.2

4

The expansion of the Association Movement was not limited to North America. Nearly one hundred delegates from nine

countries met in Paris in 1855, at the urging of Jean Henri Dunant (the founder of the International Red Cross) to

discuss the development of a global organization. By this time, 329 Associations around the world included 30,360

members, of which nearly half were from North America. The delegates adopted the Paris Basis as the organization's

primary mission:

The expansion of the Association Movement was not limited to North America. Nearly one hundred delegates from nine

countries met in Paris in 1855, at the urging of Jean Henri Dunant (the founder of the International Red Cross) to

discuss the development of a global organization. By this time, 329 Associations around the world included 30,360

members, of which nearly half were from North America. The delegates adopted the Paris Basis as the organization's

primary mission:

…to unite those young men who, regarding Jesus Christ as their God and Savior according to the Holy Scriptures, desire to be His disciples in their doctrine and in their life, and to associate their efforts for the extension of His Kingdom amongst young men.3

As a result of this meeting, the World's Alliance of YMCAs was formed to coordinate and support Association movements around the world.4

5 The North American Association grew rapidly during the remainder of the nineteenth century. The American Civil War stimulated its growth, especially in the North. The YMCA formed the United States Christian Commission to address soldiers' temporal and spiritual needs. For the first time, Association workers served soldiers-primarily Union troops-during wartime, offering wholesome Christian activities in military camps. Many soldiers were away from home for the first time, and the YMCA sought to help them maintain their moral compass and avoid the vices of military life. Over five thousand volunteers worked for the U.S. Christian Commission, assisting soldiers on the battlefield, in hospitals, in camps, and in prisoner-of-war compounds.5

6

After the war, the North American YMCA decided to expand its operations overseas to promote the Association movement. In

1866, the YMCA organized the World's Committee in New York City. This organization was renamed the International Committee

of YMCAs in 1879 and financed the development of Associations based on the North American model in Europe (especially in Germany

and France). The International Committee served as the national executive organ for the North American YMCA. The key impetus

to this work came in 1886 when 250 students, primarily YMCA members, from one hundred colleges met at Mount Hermon Boys' School near

Northfield, Massachusetts. Over one hundred students signed up as student missionaries, and they adopted the goal to "evangelize

the world in a generation." This event marked the beginning of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions (SVM)

and spurred missionary work across the country. Within three years, the North American YMCA approved foreign work (world

service) at its annual convention and appointed the association's first two secretaries, John Trumbull Swift and David

McConaughy, to begin YMCA missionary work in Japan and India, respectively.6

After the war, the North American YMCA decided to expand its operations overseas to promote the Association movement. In

1866, the YMCA organized the World's Committee in New York City. This organization was renamed the International Committee

of YMCAs in 1879 and financed the development of Associations based on the North American model in Europe (especially in Germany

and France). The International Committee served as the national executive organ for the North American YMCA. The key impetus

to this work came in 1886 when 250 students, primarily YMCA members, from one hundred colleges met at Mount Hermon Boys' School near

Northfield, Massachusetts. Over one hundred students signed up as student missionaries, and they adopted the goal to "evangelize

the world in a generation." This event marked the beginning of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions (SVM)

and spurred missionary work across the country. Within three years, the North American YMCA approved foreign work (world

service) at its annual convention and appointed the association's first two secretaries, John Trumbull Swift and David

McConaughy, to begin YMCA missionary work in Japan and India, respectively.6

7 The North American Association stressed the autonomy of national YMCA movements, both at home and abroad. Except for buildings and special projects, for which the International Committee provided monetary support, national movements were to be financially self-supporting. Local Associations and National Committees were independent of the North American Association, and its secretaries served solely in an advisory role. While North American secretaries took the initiative in organizing Associations overseas, and many held the post of General Secretary, they worked under the control of local committees. From time to time, the International Committee provided financial aid to National Committees, but this support was usually limited to specific projects and was supplemented by funds raised in the countries in question. The goal of the North American YMCA was to establish strong indigenous Association movements that were "self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating." The typical North American secretary sought to "work himself out of a job" as soon as possible, recruiting nationals whom he would train to eventually take over management of the movement. These secretaries were not sent because of their theological training, but because they were men of action. They were assigned to perform a specialized function, in which they built on, reinforced, and complemented the work of foreign Christian missionaries.7

8

In Europe, the World's Alliance was developing along similar lines. During the Conference of 1878, the World's Alliance

established its own mission organization. The Central International Committee was formed, with headquarters in Geneva,

and soon recruited a full time General Secretary. This group later became known as the World's Committee, and served to

promote the expansion of the Association movement around the globe. In contrast to the North American approach, which

favored the development of independent movements, there was a call for "the whole work … in foreign mission lands

… [to] be carried on by and exclusively under the supervision of the Central International Committee at Geneva."

In practice, the North American Association and European YMCAs conducted foreign missions without coordinating their

activities with the World's Committee for over thirty years. The World's Committee did not sponsor any overseas missions,

until 1890 when Luther D. Wishard undertook a world tour.

In Europe, the World's Alliance was developing along similar lines. During the Conference of 1878, the World's Alliance

established its own mission organization. The Central International Committee was formed, with headquarters in Geneva,

and soon recruited a full time General Secretary. This group later became known as the World's Committee, and served to

promote the expansion of the Association movement around the globe. In contrast to the North American approach, which

favored the development of independent movements, there was a call for "the whole work … in foreign mission lands

… [to] be carried on by and exclusively under the supervision of the Central International Committee at Geneva."

In practice, the North American Association and European YMCAs conducted foreign missions without coordinating their

activities with the World's Committee for over thirty years. The World's Committee did not sponsor any overseas missions,

until 1890 when Luther D. Wishard undertook a world tour.

In 1902, the World's Alliance met in Christiana (Oslo), where the delegates formulated the principles for extending the

Association into new mission fields. Four years later, the Missionary Department was established within the World's

Committee. By 1909, this department had sent three Swiss secretaries abroad, but most of the group's efforts focused

on supporting weaker European movements and sending assistance to the Armenians in Asia Minor. It was not until the

Edinburgh Conference in 1913 that Association missionary work was launched at the international level. This meeting of

all of the national YMCA movements authorized the call of "a conference of workers representing the different National

Alliances interested in missionary work in other lands."8

In 1902, the World's Alliance met in Christiana (Oslo), where the delegates formulated the principles for extending the

Association into new mission fields. Four years later, the Missionary Department was established within the World's

Committee. By 1909, this department had sent three Swiss secretaries abroad, but most of the group's efforts focused

on supporting weaker European movements and sending assistance to the Armenians in Asia Minor. It was not until the

Edinburgh Conference in 1913 that Association missionary work was launched at the international level. This meeting of

all of the national YMCA movements authorized the call of "a conference of workers representing the different National

Alliances interested in missionary work in other lands."8

9 The North American Association underwent an important reorganization in 1901 that underlined the organization's respect for independent movements. In that year, Canadian delegates formed the Canadian Committee within the International Committee, which reflected a growing Canadian consciousness within the movement. In 1912, the Canadian YMCAs met and formed a separate Canadian National Council. They agreed to meet in a national convention every three years. The Canadians still sent delegates to the International Convention conducted by the American YMCA and cooperated in Foreign Work, but the administration of Canadian associations became largely independent from American operations. This decision would have important ramifications for the American YMCA within two years.9

10  The leadership of the North American YMCA was in able hands at the turn of the century. Richard C. Morse was the General

Secretary of the International Committee, a position he had held since 1869. He was assisted by a young secretary, John R.

Mott, who had become involved in the Association movement in 1886 when he attended the Mount Hermon Conference. A Cornell

student, Mott was deeply influenced by the Association's student movement and became a leading figure in the SVM. Mott

succeeded Wishard, taking over the Student Department in the YMCA's Foreign Work, and began a long career striving to

recruit foreign students into the YMCA. He took several world tours to promote the Association movement and embraced the

organization's objective of "evangelizing the world in a generation."10 He recognized that foreign college students would be

the future leaders of their nations, and that to win them over to the Association movement would be a major step in developing

the YMCA and Christianity overseas. Mott became an important force in the Red Triangle movement and a key figure in the

World's Student Christian Federation (WSCF). In 1895, he was the leading force in establishing the WSCF and was elected

its first General Secretary. Mott was endowed with the ability to attract and recruit young men of outstanding promise to

serve the YMCA overseas. He also commanded the confidence of prominent Americans who had the financial resources to support

Association activities in foreign lands. Mott's skills as a communicator, both in writing and in person, were vital to his

success. He had a tremendous capacity for work, coupled with keen administrative skills. These traits made Mott a major force

within the American YMCA, and in 1915 Mott succeeded Morse as Secretary General of the International

Committee.11

The leadership of the North American YMCA was in able hands at the turn of the century. Richard C. Morse was the General

Secretary of the International Committee, a position he had held since 1869. He was assisted by a young secretary, John R.

Mott, who had become involved in the Association movement in 1886 when he attended the Mount Hermon Conference. A Cornell

student, Mott was deeply influenced by the Association's student movement and became a leading figure in the SVM. Mott

succeeded Wishard, taking over the Student Department in the YMCA's Foreign Work, and began a long career striving to

recruit foreign students into the YMCA. He took several world tours to promote the Association movement and embraced the

organization's objective of "evangelizing the world in a generation."10 He recognized that foreign college students would be

the future leaders of their nations, and that to win them over to the Association movement would be a major step in developing

the YMCA and Christianity overseas. Mott became an important force in the Red Triangle movement and a key figure in the

World's Student Christian Federation (WSCF). In 1895, he was the leading force in establishing the WSCF and was elected

its first General Secretary. Mott was endowed with the ability to attract and recruit young men of outstanding promise to

serve the YMCA overseas. He also commanded the confidence of prominent Americans who had the financial resources to support

Association activities in foreign lands. Mott's skills as a communicator, both in writing and in person, were vital to his

success. He had a tremendous capacity for work, coupled with keen administrative skills. These traits made Mott a major force

within the American YMCA, and in 1915 Mott succeeded Morse as Secretary General of the International

Committee.11

11

Mott was ably assisted by a group of talented and experienced Association men. Edward C. Jenkins took over the Foreign

Work Department of the International Committee in 1913. He had been Mott's private secretary for over ten years and was

a talented administrator. The war placed greater responsibilities on Jenkins as he took on an increasing load of the

Association's overseas work.

Mott was ably assisted by a group of talented and experienced Association men. Edward C. Jenkins took over the Foreign

Work Department of the International Committee in 1913. He had been Mott's private secretary for over ten years and was

a talented administrator. The war placed greater responsibilities on Jenkins as he took on an increasing load of the

Association's overseas work.

Fletcher S. Brockman, another important leader of the Association, became caught up in the enthusiasm of the SVM while

studying to become a minister and missionary to China at Vanderbilt University. In 1898, Brockman traveled to China

as a Student Secretary of the YMCA and worked to develop American interest in and financial support for Association

missionary work in the Far East. When Mott became General Secretary in 1915, he insisted that Brockman be appointed

as Associate General Secretary in charge of the Home and Foreign Divisions. Mott, Jenkins, and Brockman represented

the nucleus of the American YMCA as the war in Europe erupted, and would lead the Association through the terrible

"trial by fire" that threatened the movement around the globe.12

Fletcher S. Brockman, another important leader of the Association, became caught up in the enthusiasm of the SVM while

studying to become a minister and missionary to China at Vanderbilt University. In 1898, Brockman traveled to China

as a Student Secretary of the YMCA and worked to develop American interest in and financial support for Association

missionary work in the Far East. When Mott became General Secretary in 1915, he insisted that Brockman be appointed

as Associate General Secretary in charge of the Home and Foreign Divisions. Mott, Jenkins, and Brockman represented

the nucleus of the American YMCA as the war in Europe erupted, and would lead the Association through the terrible

"trial by fire" that threatened the movement around the globe.12

The Goals of the American YMCA

12 The Young Men's Christian Association had grown both in size and scope between 1844 and 1914. The primary objective of the organization was to promote high standards of Christian character in boys and young men through a variety of programs. The Association strove to assist young men at a vulnerable period in their lives, and thereby mold entire nations and eventually the world. Although the Association movement arose during the height of Western imperialism, YMCA leaders always acknowledged the independence of both domestic and foreign Associations. In Foreign Work, Mott insisted on recruiting and training foreign nationals to take over YMCA operations in their home countries as rapidly as possible. The Association sought the development of a global brotherhood based on a vision of ecumenical Christianity in which all nations, peoples, and cultural heritages would participate on a basis of equality and reciprocal respect.13

13

The YMCA sought to develop national movements that would eventually govern, sustain, and propagate themselves. In this

process, the YMCA cooperated with church missions, although the Association was a lay enterprise. Secretaries were not

to compete with sectarian missionaries, but would encourage young men to seek church membership. The Association was

also inclusive in terms of all Christian faiths. Although a Protestant organization, the YMCA was interconfessional,

not confined to any one denomination. In Roman Catholic countries, the majority of board members and indigenous

secretaries were Catholic; the same held true in Orthodox countries, where most board members and Association workers

belonged to the Orthodox faith. In non-Christian lands (especially in South Asia, the Far East, and the Middle East),

control of the organization remained in the hands of Christians, but participation in the organization by non-Christians

was welcomed and encouraged. One important rule was that Association secretaries were not to attempt to proselytize, since

such action could lead to political and social backlash against the organization.14

The YMCA sought to develop national movements that would eventually govern, sustain, and propagate themselves. In this

process, the YMCA cooperated with church missions, although the Association was a lay enterprise. Secretaries were not

to compete with sectarian missionaries, but would encourage young men to seek church membership. The Association was

also inclusive in terms of all Christian faiths. Although a Protestant organization, the YMCA was interconfessional,

not confined to any one denomination. In Roman Catholic countries, the majority of board members and indigenous

secretaries were Catholic; the same held true in Orthodox countries, where most board members and Association workers

belonged to the Orthodox faith. In non-Christian lands (especially in South Asia, the Far East, and the Middle East),

control of the organization remained in the hands of Christians, but participation in the organization by non-Christians

was welcomed and encouraged. One important rule was that Association secretaries were not to attempt to proselytize, since

such action could lead to political and social backlash against the organization.14

14 The North American YMCA embraced the "Four-fold Program" by the beginning of World War I. This idea first emerged in the New York City YMCA mission statement in 1866, which dedicated that organization to "the improvement of the spiritual, mental, social, and physical condition of young men."15 This program centered around the Association buildings, since these facilities were specifically designed to enhance each component of the YMCA's plan. Physical education was a key element of this program, and most Association buildings featured a gymnasium, a swimming pool, and locker rooms. By stressing healthy competition, young men could build up their physical strength and learn the principles of fair play. Sports were a vital element of the YMCA program. Good sportsmanship was always stressed, as well as team play instead of individual ability. The Association "invented" basketball and volleyball to take full advantage of their facilities and to promote these values. Mental development was emphasized in Association classrooms, libraries, and hobby rooms. Young men could read wholesome literature and take a variety of classes in topics ranging from foreign languages to vocational development, to improve their employment opportunities. The YMCA hosted guest speakers who addressed a wide variety of topics and issues. Social development was achieved through YMCA social rooms, restaurants, and dormitories. Young men could practice their social skills at YMCA receptions. Secretaries also organized a variety of clubs where members could enjoy the companionship of like-minded individuals. Association buildings were designed to be "homes away from home," where young men could find shelter from a hostile world. Dormitories allowed members to spend the night in clean, Christian surroundings. Spiritual development was pursued through a variety of programs including Bible classes, evangelistic meetings, and general Christian fellowship. The overall aim of each of these points was character building, based on Christian principles.16

15 The North American Association focused on several target groups between its founding and the beginning of World War I. Although the first group the YMCA addressed was young men who had been suddenly thrust into urban settings, the Association quickly expanded its mission to meet the needs of other groups. The YMCA developed its first Association for Black Americans in 1853 in Washington, D.C. Although "Colored Associations" remained segregated, the organization recognized the needs of freedmen and sought to provide them with Christian service. The needs of other alienated groups were also recognized by the Association. In 1879, the YMCA opened its first Association among American Indians for Sioux in the Dakota Territory. Another important target group was college students. Away from home for the first time, college students were tempted by the opportunity to engage in immoral lifestyles. The first Student Associations emerged at Cumberland University, in Lebanon, Tennessee, and Milton Academy, in Milton, Wisconsin, in 1856. Associations for high-school students would not develop for another thirty-three years, when the first "Hi-Y" opened in Chapman, Kansas. The needs of young boys, however, especially in large cities, were first formally recognized in 1869 when the YMCA in Salem, Massachusetts opened the first Boys' Work Department. Juveniles often worked in terrible conditions, or simply "ran the streets," and the YMCA recognized that it was in society's best interests to offer boys a Christian environment in which to spend their time to avoid serious urban problems in the future.17

16 The Association also worked to improve the moral lifestyles of American workers during the later part of the nineteenth century. The first Railroad Association opened in 1872 in Cleveland, although the Executive Committee in New York sent a secretary to organize YMCAs along the Union Pacific Railroad lines in 1868. Train crews worked far from home, and the YMCA operated dormitories for these men to provide them with Christian way stations. The first permanent Rural Work organization emerged in Illinois the next year, which marked the expansion of Association service from cities to agricultural regions. To combat moral turpitude at military bases, the Association opened the first permanent Army Association at Fort Snelling in St. Paul in 1879. Soldiers could enjoy healthy entertainment in friendly surroundings while stationed far from loved ones. The YMCA established the first Navy Association in 1895 in Brooklyn, and similar organizations followed at naval stations for sailors enjoying shore leave. Associations also opened catering to miners in Pennsylvania and lumbermen in Wisconsin in 1882. By the end of the nineteenth century, the North American YMCA had developed an extensive service, meeting the disparate needs of a wide range of boys and men. These services and target groups were naturally incorporated into the Association's global efforts, as secretaries traveled overseas. The overall goal of the YMCA at the beginning of the twentieth century was to establish a fellowship among members of different races, nations, and religions that transcended age, class, and profession.18

17 The key to the success of the Association's mission was the YMCA secretary. These men were generally college-educated and had received training in YMCA methods either by working at American Associations or attending YMCA schools. The first Red Triangle institute, the International YMCA Training School, opened in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1885 and later became Springfield College. This school was followed in 1890 by the YMCA Institute and Training School, which later became George Williams College, with campuses in Chicago and Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The men who attended these schools were carefully selected and prepared to transplant the North American program overseas after years of training and practical experience. Foreign Work secretaries had the difficult task of winning the confidence and loyalty of men of other nations, races, and faiths. They had to develop the skills of promotion, administration, and self-sacrifice. Secretaries also had to be creative, stretching scarce resources as far as possible. In addition, these men served as reporters, keeping in constant touch with New York and analyzing the political, economic, social, religious, and intellectual currents of the countries to which they were assigned. Without talented secretaries, the YMCA would not have been able to establish and foster new national movements overseas.19

The Development of the German YMCA

18

The concept of a religious organization dedicated to young men developed early in Germany. Societies focusing on the

evangelization of young men emerged in 1816 as Jünglingsvereine (Young Men's Associations). To consolidate

the movement, representatives of these organizations formed the Rhine-Westphalian Alliance of Evangelical Young Men's

Associations in 1848. Members of this Alliance attended the International YMCA Convention in Paris in 1855 and were among

the founding members of the World's Alliance. The Association continued to grow across the German Empire, and in 1882 a

national convention convened, uniting the regional organizations into a national alliance. Up to this point, the German YMCA

had focused primarily on the spiritual development of young men with efforts aimed at developing religious fellowship, Bible

study, and evangelism. In 1883, a new type of Association emerged in Berlin in which social service played as important a

role as Bible study.

The concept of a religious organization dedicated to young men developed early in Germany. Societies focusing on the

evangelization of young men emerged in 1816 as Jünglingsvereine (Young Men's Associations). To consolidate

the movement, representatives of these organizations formed the Rhine-Westphalian Alliance of Evangelical Young Men's

Associations in 1848. Members of this Alliance attended the International YMCA Convention in Paris in 1855 and were among

the founding members of the World's Alliance. The Association continued to grow across the German Empire, and in 1882 a

national convention convened, uniting the regional organizations into a national alliance. Up to this point, the German YMCA

had focused primarily on the spiritual development of young men with efforts aimed at developing religious fellowship, Bible

study, and evangelism. In 1883, a new type of Association emerged in Berlin in which social service played as important a

role as Bible study.

Friedrich von Schlümbach had traveled to the United States, where he became a secretary of the International Committee.

He accepted the mission of forming and developing Associations for German-speaking young men in American cities. Due to ill

health, he returned to Germany and organized the Berlin association on the North American model. The organization was so

successful that within a year it had acquired its own building, and Christian Phildius became the Berlin YMCA's General

Secretary. This marked the beginning of the Christlicher Verein Jünger Männer (CVJM), and similar organizations

opened in other cities across Germany in the following years. Influenced by the North American YMCA, City Associations

arose across Germany, acquiring buildings and employing secretaries. Sports and physical education programs emerged in

these organizations and were added to thereligious programs. The Association movement grew rapidly in Protestant Germany. By

1900, the National Alliance appointed the German YMCA's first national General Secretary. By 1914, the German National YMCA

Council was one of the largest Associations in the World's Alliance, rivaled only by the YMCAs of North

America.20

Friedrich von Schlümbach had traveled to the United States, where he became a secretary of the International Committee.

He accepted the mission of forming and developing Associations for German-speaking young men in American cities. Due to ill

health, he returned to Germany and organized the Berlin association on the North American model. The organization was so

successful that within a year it had acquired its own building, and Christian Phildius became the Berlin YMCA's General

Secretary. This marked the beginning of the Christlicher Verein Jünger Männer (CVJM), and similar organizations

opened in other cities across Germany in the following years. Influenced by the North American YMCA, City Associations

arose across Germany, acquiring buildings and employing secretaries. Sports and physical education programs emerged in

these organizations and were added to thereligious programs. The Association movement grew rapidly in Protestant Germany. By

1900, the National Alliance appointed the German YMCA's first national General Secretary. By 1914, the German National YMCA

Council was one of the largest Associations in the World's Alliance, rivaled only by the YMCAs of North

America.20

19

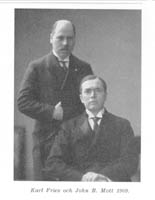

John R. Mott, future General Secretary of the American YMCA, established personal ties with the German YMCA during the

summer of 1894. His goal was to investigate conditions in Europe to determine whether students could be organized in a

global evangelization movement. Mott traveled across Ireland, England, France, and Switzerland before proceeding to Germany,

where he met with Association and student leaders. The American secretary conferred with Karl Fries, leader of the Swedish Christian Student Movement,

and accepted an invitation for American, British, and German student representatives to meet in Sweden later that summer.

Mott discussed these plans with German student leaders as he toured Cologne, Heidelberg, and Mainz. He then returned to

London to attend a student conference at Keswick. At this meeting, Mott explained his goal of transforming the Student

Volunteer Movement into a YMCA-type organization. He persuaded Fritz Mockert and Johannes Siemsen, German student leaders,

to attend the Keswick Conference, which marked the beginning of a world student Christian union. Mott then returned to

Germany to attend the Sixth German Student Conference in Cassel. One hundred German students representing two-thirds of the

empire's universities attended, as well as delegates from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Holland, and Switzerland. Mott urged the

Germans to adopt a more comprehensive program, rather than focusing primarily on Bible study and social fellowship. In

response, the delegates agreed to form the Deutsche Christliche Studenten Vereinigung (DCSV) (German Christian Student

Alliance) to promote evangelical work, support missionary activities, and help students avoid immoral temptations. The

delegates appointed Siemsen as their representative to the Scandinavian student conference, which was held in Vadstena,

Sweden in August 1894. Mott also attended the conference, which led to the creation of the World's Student Christian Federation

(WSCF).21

John R. Mott, future General Secretary of the American YMCA, established personal ties with the German YMCA during the

summer of 1894. His goal was to investigate conditions in Europe to determine whether students could be organized in a

global evangelization movement. Mott traveled across Ireland, England, France, and Switzerland before proceeding to Germany,

where he met with Association and student leaders. The American secretary conferred with Karl Fries, leader of the Swedish Christian Student Movement,

and accepted an invitation for American, British, and German student representatives to meet in Sweden later that summer.

Mott discussed these plans with German student leaders as he toured Cologne, Heidelberg, and Mainz. He then returned to

London to attend a student conference at Keswick. At this meeting, Mott explained his goal of transforming the Student

Volunteer Movement into a YMCA-type organization. He persuaded Fritz Mockert and Johannes Siemsen, German student leaders,

to attend the Keswick Conference, which marked the beginning of a world student Christian union. Mott then returned to

Germany to attend the Sixth German Student Conference in Cassel. One hundred German students representing two-thirds of the

empire's universities attended, as well as delegates from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Holland, and Switzerland. Mott urged the

Germans to adopt a more comprehensive program, rather than focusing primarily on Bible study and social fellowship. In

response, the delegates agreed to form the Deutsche Christliche Studenten Vereinigung (DCSV) (German Christian Student

Alliance) to promote evangelical work, support missionary activities, and help students avoid immoral temptations. The

delegates appointed Siemsen as their representative to the Scandinavian student conference, which was held in Vadstena,

Sweden in August 1894. Mott also attended the conference, which led to the creation of the World's Student Christian Federation

(WSCF).21

20  The first WSCF conference was held in Northfield and Williamstown, Massachusetts, in July 1897, and the assembled

representatives established the goals for the organization. Students embraced Mott's objective of "evangelization of the

world in this generation." Delegates met in Eisenach, Germany, for the next WSCF conference in July 1898. Mott, as General

Secretary of the organization, led 102 representatives from twenty-four countries. The goal of the Eisenach Conference was to bring

national student leaders together and focus their activities on European universities. While attending the conference,

Mott visited university campuses at Göttingen, Breslau, Leipzig, Halle, and Berlin, and concluded that Germany was

"the greatest student field in the world." The American secretary recognized the importance of the German YMCA in the

future of the Association movement.22

The first WSCF conference was held in Northfield and Williamstown, Massachusetts, in July 1897, and the assembled

representatives established the goals for the organization. Students embraced Mott's objective of "evangelization of the

world in this generation." Delegates met in Eisenach, Germany, for the next WSCF conference in July 1898. Mott, as General

Secretary of the organization, led 102 representatives from twenty-four countries. The goal of the Eisenach Conference was to bring

national student leaders together and focus their activities on European universities. While attending the conference,

Mott visited university campuses at Göttingen, Breslau, Leipzig, Halle, and Berlin, and concluded that Germany was

"the greatest student field in the world." The American secretary recognized the importance of the German YMCA in the

future of the Association movement.22

21 During the early 1900s, the YMCA continued to expand both in the United States and Germany. The WSCF played an important role in uniting Christian students in support of the Student Volunteer Movement. During the summer of 1909, Mott had begun a crusade to expand the YMCA in Russia and other Orthodox countries. The American YMCA supported the establishment of the Miyak (Lighthouse) in St. Petersburg in 1900. Between the General Secretary's visit to Russia and attendance at the WSCF Conference in Oxford, England in July 1909, Mott returned to Germany. He attended the Student Mission Conference in Halle, where his "world vision of student responsibility and opportunity was both an inspiration and challenge, and his stirring Macedonian call to the university men fell on responsive ears." Mott again returned to Germany in early February 1911. He spent a weekend in Berlin in preparation for the Constantinople Conference, which was designed to inaugurate Association services in Muslim countries beginning with the Ottoman Empire, before continuing on to Switzerland. Before the beginning of World War I, Mott made one more trip to Germany. The General Secretary traveled to Europe between January and April 1912, a trip that included a visit to Berlin. He worked with student leaders, including Theophile Mann and Friedrich Wilhelm Siegmund-Schultze, on the development of social centers in Germany and for the employment of a secretary to serve the large population of foreign students in the German Empire. These centers would play an important role in providing social services as the Germans mobilized for total warfare. It was clear that, well before World War I, Mott recognized the importance of German participation in the international Association movement.23

The Growth of the YMCA Movement in Austria-Hungary

22 The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary was the largest Roman Catholic state in the world before World War I. As a Protestant social welfare organization, the YMCA had a difficult time establishing itself in this empire. Henry Millard, director of the British and Foreign Bible Society, helped found the "Association of Christian Youths" in Vienna in 1873, which marked the beginning of the Association movement in the Habsburg Empire. The original members were a small group of Protestants, primarily Baptists and members of the National Protestant Church, who were later joined by Methodists. This organization rented rooms and conducted Sunday lectures and Bible classes. The organization did not gain much of a following, and had a difficult time meeting expenses. Under more efficient management, the Association began to grow in 1890, but the movement underwent a crisis when a disreputable chairman upset operations.24

23

In 1896, Christian Phildius, a German delegate to the World's Committee in Geneva, arrived in Vienna and organized a

larger circle of clergy and laymen. He invited the Association of Christian Youths to continue its activities as a YMCA

with missionary aims. He appointed Wold von Ziegler und Klipphausen, who had served as an Association secretary in Berlin,

to become the new leader of the organization. In September 1896, the Viennese YMCA held its inaugural meeting in rented (but

large and well-furnished) quarters. The new Association, the Christlicher Vereine Jünger Männer (CVJM),

became quite popular. Soon membership rose to one hundred men in the Senior Department, and 150 boys in the Junior Department.

Activities included offering an inexpensive but good supper and tea, Bible lessons, Sunday lectures, and a well-trained

choir. The Association had trouble attracting additional members, even from among the Protestants in Vienna. To recruit

new members, the Association held annual festivals, presented lectures by foreign speakers, printed books and pamphlets,

and conducted visits, but it continued to meet with only limited success. As a result, the Vienna Association was not able

to make itself independent of foreign help.25

In 1896, Christian Phildius, a German delegate to the World's Committee in Geneva, arrived in Vienna and organized a

larger circle of clergy and laymen. He invited the Association of Christian Youths to continue its activities as a YMCA

with missionary aims. He appointed Wold von Ziegler und Klipphausen, who had served as an Association secretary in Berlin,

to become the new leader of the organization. In September 1896, the Viennese YMCA held its inaugural meeting in rented (but

large and well-furnished) quarters. The new Association, the Christlicher Vereine Jünger Männer (CVJM),

became quite popular. Soon membership rose to one hundred men in the Senior Department, and 150 boys in the Junior Department.

Activities included offering an inexpensive but good supper and tea, Bible lessons, Sunday lectures, and a well-trained

choir. The Association had trouble attracting additional members, even from among the Protestants in Vienna. To recruit

new members, the Association held annual festivals, presented lectures by foreign speakers, printed books and pamphlets,

and conducted visits, but it continued to meet with only limited success. As a result, the Vienna Association was not able

to make itself independent of foreign help.25

24 Despite the limited growth in the capital, the Association movement did spread to other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Christian Phildius worked hard to found new branches throughout the empire beginning in 1896. Most of this growth occurred in the German-speaking parts of the Dual Monarchy where laymen seized the initiative. Protestant pastors had limited resources to pursue YMCA development, and concentrated their efforts on their parishes. Traditionally, the pastor was responsible for religious work in Austria-Hungary and few laymen had either the talent or the inclination to serve young people. Despite these limitations, Associations developed in Graz, Linz, and Salzburg in Austria. Additional YMCA groups later emerged in Bohemia, Moravia, Galicia, Bukovina, and Hungary before the onset of World War I. In 1897, Phildius helped organize an Austrian National Union, which was divided into several national branch-associations. But because of strained relations between the various nationalities, the National Union achieved few significant successes. The Union became useful only when the monarchy went to war in 1914, as a means of coordinating YMCA operations in Austria-Hungary.26

25  The Hungarian Association, or Magyar Evangeliumi Keresztyen Diakszöveteg, had even earlier roots than its Austrian

counterpart. The Association movement in Hungary began in October 1883, when Charles Fermaud of the World's Alliance

delivered lectures on the YMCA across the kingdom. The Hungarian YMCA was primarily a Protestant evangelical movement

that focused on religious development.

The Hungarian Association, or Magyar Evangeliumi Keresztyen Diakszöveteg, had even earlier roots than its Austrian

counterpart. The Association movement in Hungary began in October 1883, when Charles Fermaud of the World's Alliance

delivered lectures on the YMCA across the kingdom. The Hungarian YMCA was primarily a Protestant evangelical movement

that focused on religious development.

The Association grew, and in October 1900 began publication of a monthly magazine entitled Ebresztö (The Faith).

By 1908, the Hungarian YMCA had established an extensive printing organization in Budapest, primarily reprinting the works

of foreign Association leaders including John Mott, Karl Fries, J. H. Oldham, and J. Edward Bosworth, as well as the writings

and speeches of Hungarian YMCA leaders such as Jonas Victor, Geza Takaro, and Jozsef Pongracz.27

The Association grew, and in October 1900 began publication of a monthly magazine entitled Ebresztö (The Faith).

By 1908, the Hungarian YMCA had established an extensive printing organization in Budapest, primarily reprinting the works

of foreign Association leaders including John Mott, Karl Fries, J. H. Oldham, and J. Edward Bosworth, as well as the writings

and speeches of Hungarian YMCA leaders such as Jonas Victor, Geza Takaro, and Jozsef Pongracz.27

26 The first YMCA building in Vienna was owned by the Cistercians, a Roman Catholic monastic order. While the Protestant organization's activities were not initially of any concern to its landlord, after a few years, the Archbishop of Vienna gave the Association a notice to vacate the premises. This marked the first tensions between the YMCA and Catholic authorities in Austria. As a result, the Vienna Association had to move to new rented quarters in 1901. The membership recognized the importance of purchasing their own building. Between 1906 and 1911, when Karl Füchtner was the Association Secretary, a building fund was established. With aid from Phildius and the World's Alliance in Geneva, along with Hermann Helbing, the German National Secretary, the Vienna YMCA was able to collect money to purchase land for construction. The new Association building was formally inaugurated on 31 October 1912. Just as operations were established, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war against Serbia in July 1914, and the Austrian YMCA took on a new social welfare mission.28

The YMCA and Bulgaria

27 As an Orthodox country, Bulgaria was an important mission ground for both the World's Alliance of YMCAs and the International Committee of the American YMCA. American interest in Bulgaria began before the creation of the modern nation. In 1840, American missionary Elias Riggs helped the Orthodox monk Neophytos translate the Bible into Bulgarian. This translation became part of a nationalist cultural movement that eventually challenged and overthrew Ottoman rule. The first American missionaries arrived in Bulgaria in 1858, and James F. Clarke founded the Samokov Seminary three years later. Religious revivalism in Bulgaria accelerated among the Orthodox Christians at this time. With the permission of the Turkish Sultan, the Greek Orthodox Church reestablished the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870. This body received jurisdiction over large sections of Macedonia and Thrace, as well as Bulgaria (the national Bulgarian Orthodox Church was promptly excommunicated by a Greek Orthodox council in 1872; a reconciliation with Constantinople was not effected until 1945). In 1875, the Bulgarian people began their insurrection against the Ottomans, which resulted in atrocities committed by Turkish irregulars. A small Bulgarian semi-autonomous principality emerged in July 1878 as part of the Treaty of Berlin, but the Bulgarians and Russians both had aspirations for a greater Bulgaria. Continued tensions with Serbia and the Ottoman Empire did not stifle these ambitions. In 1908, Tsar Ferdinand declared Bulgaria's independence from Ottoman suzerainty during the Bosnian annexation crisis.29

28 The new kingdom played a critical role in Balkan politics. Bulgaria allied with Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece, and went to war against Turkey in October 1912. The Bulgarians won a series of victories, forcing the Ottomans to accept an armistice in April 1913. But the other Balkan powers were envious of Bulgaria's gains, and the Second Balkan War began in June 1913. Serbia, Greece, Romania, and Turkey allied and quickly defeated the Bulgarians. Under the Treaty of Bucharest in August, the Bulgarians lost eastern Macedonia to Serbia, Salonika to Greece, and southern Dobrudja to Romania. They also had to relinquish Adrianople and western Thrace to the Turks under the terms of the Treaty of Constantinople in September 1913. Despite the kingdom's gains in Macedonia, and the acquisition of access to the Aegean Sea, the two wars had a devastating effect on the country. Bulgaria's decision to enter World War I in October 1915 would further devastate the war-torn nation.30

29

The YMCA established early roots in Bulgaria, especially in light of its Orthodox composition. Of a total population

of 3.7 million people in 1900, approximately 82 percent belonged to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. The next largest

confessional group was Muslim, numbering 642,500 (17 percent), followed by approximately fifty thousand members of the Armenian

Orthodox Church, thirty-two thousand Jews, and twenty-seven thousand Roman Catholics. The four thousand Protestants in Bulgaria (about one-tenth of one

percent of the population) formed the core of the Association movement in the kingdom. Despite their small numbers,

American Protestant churches were very active in the newly independent country, especially in the nation's school system.

Francis Clarke introduced the Christian Endeavor Society in Bulgaria in 1888 with the support of the Congregational

Church. This organization was dedicated to the promotion of Christian welfare among young men in the kingdom. In 1899,

the First Evangelical Church (Congregationalist) set up the Kotva (Anchor) organization in Sofia. This youth

movement program had a secondary Christian character. Through the efforts of an Association secretary supported by the

World's Alliance in Geneva, the organization was remodeled as a YMCA. For three years it remained an organization for

men only, but in 1902 the Association accepted women members (an unusual move for YMCAs at this time). Membership was

ecumenical and included Protestants, Orthodox Christians, and Roman Catholics. The Methodists formed another youth

organization, the Epworth League, in Bulgaria in 1904. During a visit to Bulgaria in 1910, Christian Phildius and Charles

Fermaud, the General Secretaries of the World's Alliance, helped to organize the Bulgarian Alliance of YMCAs. To consolidate

work for Bulgarian youth, Kotva formed the Federation of Young People's Christian Organizations, which also included

the Christian Endeavor Societies and the Epworth League associations. The Federation of Young People's Christian Organizations

gained admission into the World's Alliance at the World's Conference at Edinburgh in 1910. Despite the expansion of these

youth movements, they remained predominantly Protestant organizations. In the minds of most Bulgarians, the YMCA was

a Protestant body, even with its ecumenical membership.31

The YMCA established early roots in Bulgaria, especially in light of its Orthodox composition. Of a total population

of 3.7 million people in 1900, approximately 82 percent belonged to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. The next largest

confessional group was Muslim, numbering 642,500 (17 percent), followed by approximately fifty thousand members of the Armenian

Orthodox Church, thirty-two thousand Jews, and twenty-seven thousand Roman Catholics. The four thousand Protestants in Bulgaria (about one-tenth of one

percent of the population) formed the core of the Association movement in the kingdom. Despite their small numbers,

American Protestant churches were very active in the newly independent country, especially in the nation's school system.

Francis Clarke introduced the Christian Endeavor Society in Bulgaria in 1888 with the support of the Congregational

Church. This organization was dedicated to the promotion of Christian welfare among young men in the kingdom. In 1899,

the First Evangelical Church (Congregationalist) set up the Kotva (Anchor) organization in Sofia. This youth

movement program had a secondary Christian character. Through the efforts of an Association secretary supported by the

World's Alliance in Geneva, the organization was remodeled as a YMCA. For three years it remained an organization for

men only, but in 1902 the Association accepted women members (an unusual move for YMCAs at this time). Membership was

ecumenical and included Protestants, Orthodox Christians, and Roman Catholics. The Methodists formed another youth

organization, the Epworth League, in Bulgaria in 1904. During a visit to Bulgaria in 1910, Christian Phildius and Charles

Fermaud, the General Secretaries of the World's Alliance, helped to organize the Bulgarian Alliance of YMCAs. To consolidate

work for Bulgarian youth, Kotva formed the Federation of Young People's Christian Organizations, which also included

the Christian Endeavor Societies and the Epworth League associations. The Federation of Young People's Christian Organizations

gained admission into the World's Alliance at the World's Conference at Edinburgh in 1910. Despite the expansion of these

youth movements, they remained predominantly Protestant organizations. In the minds of most Bulgarians, the YMCA was

a Protestant body, even with its ecumenical membership.31

30  For both the International Committee and the World's Alliance, Bulgaria was an important mission field. Beginning with

the World Student Christian Federation Convention in Constantinople in 1911, the YMCA was interested in expanding its

services to the Orthodox nations of Eastern Europe. John R. Mott visited Sofia after this convention and held a series

of important meetings. At the invitation of the Minister of Education, Mott spoke to students at the University of Sofia.

He met with Metropolitan Stefan, spiritual leader of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, and addressed the Bulgarian Orthodox

Church seminary. He also had a thirty-minute conference with Tsarina Eleonore, Baron Paul Nicolay of the Miyak (the

Russian YMCA), and Professor Stefan Panaretoff of Robert College, who served as interpreter. The Empress expressed lively

interest in the work the YMCA had accomplished, and assured the Association representatives that she would do all in her

power to cooperate with the organization. Mott recommended the promotion of Bible study classes and provisions for student

hostels as immediate projects, proposals to which the Tsarina responded favorably.32

For both the International Committee and the World's Alliance, Bulgaria was an important mission field. Beginning with

the World Student Christian Federation Convention in Constantinople in 1911, the YMCA was interested in expanding its

services to the Orthodox nations of Eastern Europe. John R. Mott visited Sofia after this convention and held a series

of important meetings. At the invitation of the Minister of Education, Mott spoke to students at the University of Sofia.

He met with Metropolitan Stefan, spiritual leader of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, and addressed the Bulgarian Orthodox

Church seminary. He also had a thirty-minute conference with Tsarina Eleonore, Baron Paul Nicolay of the Miyak (the

Russian YMCA), and Professor Stefan Panaretoff of Robert College, who served as interpreter. The Empress expressed lively

interest in the work the YMCA had accomplished, and assured the Association representatives that she would do all in her

power to cooperate with the organization. Mott recommended the promotion of Bible study classes and provisions for student

hostels as immediate projects, proposals to which the Tsarina responded favorably.32

31 After the Second National Congress of YMCAs in 1912, the French Swiss YMCA became interested in developing Association work in Bulgaria and decided to send assistance to Sofia. They dispatched an experienced secretary, Henri Johannot of Geneva, who arrived in January 1914. Unfortunately, Johannot was able to work for only eight months before World War I broke out, but he was able to expand Association activities and prepared for the post-war development of the Bulgarian movement. By 1914, there were twenty-seven Associations throughout the kingdom, and most were connected to Protestant churches. Due to wartime mobilization, the National Committee lost most of its members and the Association could do little but mark time.33

Expansion into the Islamic World - The YMCA and the Ottoman Empire

32 The Ottoman Empire presented a major challenge for the American YMCA before World War I. This nation was the key to the Near East and the center of the Muslim world. The Ottoman Sultan was also the Caliph and supreme head of "Mohammedanism." Ruled from Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire spread across three continents at the turn of the century: Ottoman Europe included Thrace, Monastir, Albania, and Salonica; Ottoman North Africa consisted of Libya, as well as suzerainty over Egypt; and Ottoman Asia was composed of Anatolia, Armenia, Kurdistan, Syria, Mesopotamia (as far as the Persian Gulf), Palestine, and Arabia (the western coast of the Saudi Arabian peninsula). The Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina, as well as Jerusalem, were also ruled by the Turks. In 1900, 38.8 million people lived in this polyglot empire. The predominant religion was Islam, with over 29.8 million (over 77 percent) Turks and Arabs professing this faith. A large Christian minority (8.5 million, or 22 percent) also lived in the Ottoman Empire. These Christian groups included Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, and Syrian Christians. Other faiths included Jews (eighty thousand) and Roman Catholics (seventy-five thousand), but they were a negligible minority.34

33

To gain a toehold in the Ottoman Empire, the American YMCA sought to establish an Association in Constantinople. This

city was among the most cosmopolitan in the world. It was the capital of Turkey and the home of the Sublime Porte, making

it the most important center of Islam. Constantinople was the dominant religious center of the Levant : it served as the

residence of Sheikh-ul-Islam (the judicial head of the Muslim world); the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox

Church; the Armenian Patriarch; the heads of the Syrian, Jacobite, and other Eastern churches; the Legate of the Pope;

the Grand Rabbi of the Jews of the Emigration; and the headquarters of the Protestant Christians operating in the Near

East. The Association believed that its program could harmonize these diverse races, languages, and religions to draw

together the Christian sects (Protestant, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Eastern churches) and gain access to the

previously inaccessible Muslim world. The YMCA set an ambitious agenda for introducing and expanding operations in the

Ottoman Empire.35

To gain a toehold in the Ottoman Empire, the American YMCA sought to establish an Association in Constantinople. This

city was among the most cosmopolitan in the world. It was the capital of Turkey and the home of the Sublime Porte, making

it the most important center of Islam. Constantinople was the dominant religious center of the Levant : it served as the

residence of Sheikh-ul-Islam (the judicial head of the Muslim world); the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox

Church; the Armenian Patriarch; the heads of the Syrian, Jacobite, and other Eastern churches; the Legate of the Pope;

the Grand Rabbi of the Jews of the Emigration; and the headquarters of the Protestant Christians operating in the Near

East. The Association believed that its program could harmonize these diverse races, languages, and religions to draw

together the Christian sects (Protestant, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Eastern churches) and gain access to the

previously inaccessible Muslim world. The YMCA set an ambitious agenda for introducing and expanding operations in the

Ottoman Empire.35

34 For the American YMCA, spreading Christianity around the world in this generation was a major goal. Though the teeming masses of China and India were major target groups, the peoples of the Ottoman Empire were also important. The Association wanted to establish a presence in the heart of the Muslim world, as well as gain access to Jerusalem. The International Committee of the American YMCA first expressed interest in setting up a mission field in the Ottoman Empire in 1884, but the Association did not find Turkish authorities receptive to American overtures. Conservative Muslim officials tended to treat foreign youth organizations as potentially seditious and a threat to the government. Instead, the YMCA movement worked through missionaries and their educational programs. The primary vehicle of Association infiltration was the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, based in Boston. This organization founded Christian colleges across the Ottoman Empire, including Robert College in Constantinople, the International College in Smyrna, the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, Anatolia College, and St. Paul's College in Tarsus. Christian Endeavor Societies and YMCAs formed among the student bodies of these schools, and they became the nucleus of the Association movement in Turkey.36

35  John R. Mott expressed a major interest in opening the Ottoman Empire to the YMCA as General Secretary of the World's

Student Christian Federation (WSCF). Mott traveled to Constantinople in October 1895 to determine what could be done

to expand the Student Volunteer Movement in the Orient. During his six-day visit to Robert College, the Turks conducted

a reign of terror against the Armenians which forced Mott to conclude that there would be no real peace "for the

Christian peoples scattered throughout Asia Minor and along the Bosporus until this barbarous Ottoman Government is

swept from the face of the earth."37 Despite this pessimistic

appraisal, the movement continued to expand in the empire.

John R. Mott expressed a major interest in opening the Ottoman Empire to the YMCA as General Secretary of the World's

Student Christian Federation (WSCF). Mott traveled to Constantinople in October 1895 to determine what could be done

to expand the Student Volunteer Movement in the Orient. During his six-day visit to Robert College, the Turks conducted

a reign of terror against the Armenians which forced Mott to conclude that there would be no real peace "for the

Christian peoples scattered throughout Asia Minor and along the Bosporus until this barbarous Ottoman Government is

swept from the face of the earth."37 Despite this pessimistic

appraisal, the movement continued to expand in the empire.

In 1900, the World's Alliance of YMCAs recognized an Association in Constantinople. In addition, German nationals in

the capital formed their own YMCA branch. Conditions in the empire improved radically after the Restoration of the

Constitution in July 1908. Sultan Abdul Hamid II renounced the Constitution of 1876 two years after its promulgation,

and ruled the empire as a tyrannical despot for thirty years. To counter political opposition, Abdul Hamid hoped to

bolster support for his reign by reestablishing constitutional rule. The rise of the Young Turks ended conservative rule

and promised liberal reforms. The Young Turks, represented by the Party of Union and Progress, sought to reverse the

empire's decline and place the country under a competent, nationalist government. When Abdul Hamid supported a failed

counter-revolution in April 1909, the Turkish parliament unanimously voted to depose the Sultan. He was succeeded by his

brother, Mohammed V, a weak ruler who allowed the Young Turks to govern the country.38

In 1900, the World's Alliance of YMCAs recognized an Association in Constantinople. In addition, German nationals in

the capital formed their own YMCA branch. Conditions in the empire improved radically after the Restoration of the

Constitution in July 1908. Sultan Abdul Hamid II renounced the Constitution of 1876 two years after its promulgation,

and ruled the empire as a tyrannical despot for thirty years. To counter political opposition, Abdul Hamid hoped to

bolster support for his reign by reestablishing constitutional rule. The rise of the Young Turks ended conservative rule

and promised liberal reforms. The Young Turks, represented by the Party of Union and Progress, sought to reverse the

empire's decline and place the country under a competent, nationalist government. When Abdul Hamid supported a failed

counter-revolution in April 1909, the Turkish parliament unanimously voted to depose the Sultan. He was succeeded by his

brother, Mohammed V, a weak ruler who allowed the Young Turks to govern the country.38

36

The American YMCA renewed its interest in Turkey after the restoration of constitutional rule. The International Committee

recognized Lawson P. Chambers, the son of an American Board missionary, as an official secretary (without financial support)

in 1908. With Mott's approval, Chambers formed an advisory committee in Constantinople as the first step towards establishing

an Association in the capital. In response to requests from many residents in the city, the International Committee appointed

a Board of Managers for a nascent Association. In September 1910, the International Committee dispatched its first Traveling

Secretary for the Levant, Ernst O. Jacob. The International Committee defined the Levant as the Eastern Mediterranean region,

from Greece to Egypt, which was primarily Turkish territory. Shortly thereafter, the International Committee appointed Darius

A. Davis to serve as the Secretary for Constantinople.

The American YMCA renewed its interest in Turkey after the restoration of constitutional rule. The International Committee

recognized Lawson P. Chambers, the son of an American Board missionary, as an official secretary (without financial support)

in 1908. With Mott's approval, Chambers formed an advisory committee in Constantinople as the first step towards establishing

an Association in the capital. In response to requests from many residents in the city, the International Committee appointed

a Board of Managers for a nascent Association. In September 1910, the International Committee dispatched its first Traveling

Secretary for the Levant, Ernst O. Jacob. The International Committee defined the Levant as the Eastern Mediterranean region,

from Greece to Egypt, which was primarily Turkish territory. Shortly thereafter, the International Committee appointed Darius

A. Davis to serve as the Secretary for Constantinople.

Mott ordered Davis to study the situation in the capital in preparation for the establishment of an Association. Both Davis

and Jacob prepared for the WSCF Convention held in Constantinople in April 1911. Mott planned and supervised this meeting

as the best means for the Association to enter the Islamic world. By developing contacts with Muslim intellectuals, the

American General Secretary hoped to open doors in the Ottoman Empire. He planned to set up secretaries in Constantinople,

the political center of the empire, and in Cairo, the intellectual center. In many ways, the Constantinople Conference was

an ecumenical experiment, whereby the Association could expand the movement to include Orthodox and even Muslim members.

The YMCA would be taking an important step towards the "globalization" of the Association movement.39

Mott ordered Davis to study the situation in the capital in preparation for the establishment of an Association. Both Davis

and Jacob prepared for the WSCF Convention held in Constantinople in April 1911. Mott planned and supervised this meeting

as the best means for the Association to enter the Islamic world. By developing contacts with Muslim intellectuals, the

American General Secretary hoped to open doors in the Ottoman Empire. He planned to set up secretaries in Constantinople,

the political center of the empire, and in Cairo, the intellectual center. In many ways, the Constantinople Conference was

an ecumenical experiment, whereby the Association could expand the movement to include Orthodox and even Muslim members.

The YMCA would be taking an important step towards the "globalization" of the Association movement.39

37

In May 1911, the General Committee of the Union of Christian Associations in Turkey held its first meeting at Robert College

in Constantinople. Members of this committee included Davis and Jacob and representatives from Student Associations formed

by the American Board of Commissioners from Marash, Tarsus, Talas, Smyrna, Broussa, Marsovan, Van, Adabazar, Beirut, and

Constantinople. The success of the WSCF Convention and the General Committee persuaded the International Committee to

augment the American YMCA staff in Turkey. In 1911, the American Association sent Dirk Johannes Van Bommel, a Dutch national

who had recently graduated from Springfield College, to serve in Constantinople. Van Bommel arrived in Turkey in January 1912,

and the three American secretaries divided up their responsibilities: Jacob took on the task of national planning and organization;

Davis accepted responsibility for developing the Constantinople association and took Turkish classes; and Van Bommel would

assist in Constantinople, but would study Greek as a means to incorporate Armenian and Greek Orthodox members into the

Association.40

In May 1911, the General Committee of the Union of Christian Associations in Turkey held its first meeting at Robert College

in Constantinople. Members of this committee included Davis and Jacob and representatives from Student Associations formed

by the American Board of Commissioners from Marash, Tarsus, Talas, Smyrna, Broussa, Marsovan, Van, Adabazar, Beirut, and

Constantinople. The success of the WSCF Convention and the General Committee persuaded the International Committee to

augment the American YMCA staff in Turkey. In 1911, the American Association sent Dirk Johannes Van Bommel, a Dutch national

who had recently graduated from Springfield College, to serve in Constantinople. Van Bommel arrived in Turkey in January 1912,

and the three American secretaries divided up their responsibilities: Jacob took on the task of national planning and organization;

Davis accepted responsibility for developing the Constantinople association and took Turkish classes; and Van Bommel would

assist in Constantinople, but would study Greek as a means to incorporate Armenian and Greek Orthodox members into the

Association.40

38

The Association continued to grow through the work of the American staff. Davis enlisted influential members for a Board

of Managers to direct a permanent organization. By 1913, they had acquired temporary YMCA quarters in Pera, in Constantinople,

property that was formerly occupied by the American consulate. In June 1913, the twenty-one Associations in Turkey formed a

Union, which the World's Alliance recognized as a member organization at the Edinburgh Conference. In response to these

developments, the International Committee voted to provide a $75,000 building fund to the Constantinople Association,

although Mott encouraged Davis to raise contributions locally for the purchase of property. By September, Van Bommel was