Table of Contents

Chapter 3

The U.S. Government and Prisoner-of-War Responsibilities

1 The outbreak of war in Europe had important ramifications for the U.S. diplomatic corps. By 1914, war had become "civilized," in that a series of international laws had codified the conduct of warfare. The humane treatment of war prisoners was a relatively recent conceptual development. Since Biblical times, the capture of enemy troops led either to their death or enslavement. During the Middle Ages, nobles received somewhat better treatment than other combatants because they could be exchanged for ransom. By the eighteenth century, the situation for POWs in general began to improve. During the American Revolutionary War, large prison camp systems had not yet been developed. The Britishs imprisoned captured Americans on rotting hulks at sea in primitive conditions. If captured troops were willing to give their "parole," or promise that they would not take up arms again against the enemy for the duration of the war, the prisoners could return home. The care and feeding of large numbers of enemy troops was still too daunting a task for most belligerents. This was, however, the Age of Reason, and philosophers had an important impact on POW policy. Jean Jacques Rousseau argued in 1762 that war prisoners were men who were endowed with natural rights. No captor had the right to take the lives of prisoners; instead, they should be treated humanely.1

2

The first concrete steps towards the humane treatment of POWs began shortly after the Italian War of Reunification.

Henri Dunant viewed the suffering of the wounded at the Battle of Solferino and, in 1862, wrote Souvenirs de

Solferino, which described the terrible conditions he observed. Dunant's work led to the establishment of the

International Red Cross and many national Red Cross Societies. His efforts also led to an international conference

on POWs in Geneva in 1864. Delegates took the first steps toward outlining a legal framework regarding the care and

treatment of prisoners of war in the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Wounded in Armies of

the Field." At the same time, the American Civil War was raging in the United States, and both the Confederate and

Union armies amassed large numbers of prisoners in compound systems. During the first part of the war, both sides

exchanged POWs to relieve prison conditions. When the North suspected Confederates of breaking their parole by taking

up arms again against the Union, however, the Federals ended the exchange system, forcing prisoners to wait out the

war in crowded, and often unsanitary, conditions. Francis Lieber studied the POW problem and attempted to codify the

treatment of war prisoners in 1863. He wrote a set of directives for the Union armies entitled "Instructions for the

Government of Armies of the United States in the Field," which regulated the treatment of Confederate prisoners.

These instructions became the focus of an international attempt to codify Lieber's work into international law. In

1874, delegates met at a conference in Brussels to extend his ideas into global practice.2

The first concrete steps towards the humane treatment of POWs began shortly after the Italian War of Reunification.

Henri Dunant viewed the suffering of the wounded at the Battle of Solferino and, in 1862, wrote Souvenirs de

Solferino, which described the terrible conditions he observed. Dunant's work led to the establishment of the

International Red Cross and many national Red Cross Societies. His efforts also led to an international conference

on POWs in Geneva in 1864. Delegates took the first steps toward outlining a legal framework regarding the care and

treatment of prisoners of war in the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Wounded in Armies of

the Field." At the same time, the American Civil War was raging in the United States, and both the Confederate and

Union armies amassed large numbers of prisoners in compound systems. During the first part of the war, both sides

exchanged POWs to relieve prison conditions. When the North suspected Confederates of breaking their parole by taking

up arms again against the Union, however, the Federals ended the exchange system, forcing prisoners to wait out the

war in crowded, and often unsanitary, conditions. Francis Lieber studied the POW problem and attempted to codify the

treatment of war prisoners in 1863. He wrote a set of directives for the Union armies entitled "Instructions for the

Government of Armies of the United States in the Field," which regulated the treatment of Confederate prisoners.

These instructions became the focus of an international attempt to codify Lieber's work into international law. In

1874, delegates met at a conference in Brussels to extend his ideas into global practice.2

3

The most important provisions for POW treatment were embodied in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Tsar

Nicholas II of Russia invited representatives from Europe, Asia (China, Japan, Siam, and Persia), and the United

States to the first conference, which opened in The Hague in May 1899. The delegates met hoping to maintain peace,

but planned to minimize the cruelties of battle on land and sea if war were to erupt. The representatives sought to

reduce armaments, set up a system of arbitration, and humanize the rules of warfare. They acknowledged that a community

of nations existed, whereby all nations were linked by trade and the movement of people. Powerful nations owed it to

the rest of the global community to forego their military advantages and accept the mediation process as the optimal

way to settle disputes. The participants drew up conventions for the conduct of land warfare and the humane treatment

of prisoners and non-combatants. They standardized the Geneva Convention of 1864 for the protection of the wounded

and adopted guidelines for the proper care of prisoners and the treatment of people in conquered and occupied

territories. The delegates also created the Arbitration Tribunal, where nations could voluntarily bring their disputes

for adjudication by an international court.3

The most important provisions for POW treatment were embodied in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Tsar

Nicholas II of Russia invited representatives from Europe, Asia (China, Japan, Siam, and Persia), and the United

States to the first conference, which opened in The Hague in May 1899. The delegates met hoping to maintain peace,

but planned to minimize the cruelties of battle on land and sea if war were to erupt. The representatives sought to

reduce armaments, set up a system of arbitration, and humanize the rules of warfare. They acknowledged that a community

of nations existed, whereby all nations were linked by trade and the movement of people. Powerful nations owed it to

the rest of the global community to forego their military advantages and accept the mediation process as the optimal

way to settle disputes. The participants drew up conventions for the conduct of land warfare and the humane treatment

of prisoners and non-combatants. They standardized the Geneva Convention of 1864 for the protection of the wounded

and adopted guidelines for the proper care of prisoners and the treatment of people in conquered and occupied

territories. The delegates also created the Arbitration Tribunal, where nations could voluntarily bring their disputes

for adjudication by an international court.3

4

A second Hague peace conference followed in June 1907, at the suggestion of Theodore Roosevelt, and forty-four

countries from both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres participated. The conference opened with a great deal of

optimism, and the delegates did manage to agree on new limitations on the conduct of war and for the protection

of neutrals and non-combatants. Unfortunately, the representatives could not agree on an obligatory arbitral court.

The treaty was further weakened by the provision that the conventions were not binding on any power that withheld

ratification; none of the conventions were ratified without reservations by some of the powers. In October 1907,

the delegates adopted fourteen international conventions and one declaration that governed the rules of warfare.

The Hague Conventions represented the triumph of liberal ideology in terms of standardizing the rules of war. They

legislated the humane treatment of prisoners and required their swift repatriation after the end of hostilities.

The treaties represented the best of Enlightenment thought, whereby reason triumphed over instincts, and reflected

the Anglo-American belief in legal frameworks to restrain the cruelties of war. While these conventions provided

some restraints in minor disagreements, the true test would come with their application in a world war.4

A second Hague peace conference followed in June 1907, at the suggestion of Theodore Roosevelt, and forty-four

countries from both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres participated. The conference opened with a great deal of

optimism, and the delegates did manage to agree on new limitations on the conduct of war and for the protection

of neutrals and non-combatants. Unfortunately, the representatives could not agree on an obligatory arbitral court.

The treaty was further weakened by the provision that the conventions were not binding on any power that withheld

ratification; none of the conventions were ratified without reservations by some of the powers. In October 1907,

the delegates adopted fourteen international conventions and one declaration that governed the rules of warfare.

The Hague Conventions represented the triumph of liberal ideology in terms of standardizing the rules of war. They

legislated the humane treatment of prisoners and required their swift repatriation after the end of hostilities.

The treaties represented the best of Enlightenment thought, whereby reason triumphed over instincts, and reflected

the Anglo-American belief in legal frameworks to restrain the cruelties of war. While these conventions provided

some restraints in minor disagreements, the true test would come with their application in a world war.4

5

The fifth convention had a particularly important bearing on the U.S. government after most nations in Europe went

to war. This agreement governed the rights and duties of neutral states and individuals in land warfare. The United

States, as one of the few neutral Great Powers, accepted responsibility for the interests of many Allied countries

in the Central Power states as nations entered the war. By early 1915, the U.S. government represented the interests

of Great Britain, Germany, and Austria-Hungary around the globe, and these responsibilities grew as other lesser powers

joined the conflict. American diplomatic officials and belligerent governments negotiated endlessly about the actual

implementation of the provisions of the Hague Conventions, since the conventions were interpreted in different ways

by each of the belligerents. For James W. Gerard (U.S. Ambassador to Germany, 1913-1917), Frederic Courtland Penfield

(U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, 1913-1917), and Henry Morgenthau (U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, 1913-1916),

the trials and demands of POW relief work were one of many challenges associated with neutral responsibilities that taxed

and strained their embassies' limited resources.5

The fifth convention had a particularly important bearing on the U.S. government after most nations in Europe went

to war. This agreement governed the rights and duties of neutral states and individuals in land warfare. The United

States, as one of the few neutral Great Powers, accepted responsibility for the interests of many Allied countries

in the Central Power states as nations entered the war. By early 1915, the U.S. government represented the interests

of Great Britain, Germany, and Austria-Hungary around the globe, and these responsibilities grew as other lesser powers

joined the conflict. American diplomatic officials and belligerent governments negotiated endlessly about the actual

implementation of the provisions of the Hague Conventions, since the conventions were interpreted in different ways

by each of the belligerents. For James W. Gerard (U.S. Ambassador to Germany, 1913-1917), Frederic Courtland Penfield

(U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, 1913-1917), and Henry Morgenthau (U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, 1913-1916),

the trials and demands of POW relief work were one of many challenges associated with neutral responsibilities that taxed

and strained their embassies' limited resources.5

Representing Allied Interests in Germany

6

Gerard accepted an important responsibility when he became the United States Ambassador to Germany in September 1913.

When he arrived in Berlin, he found the former ambassador's quarters inadequate for business needs. Unlike other

countries, the U.S. government did not own embassies abroad or even rent suitable buildings. Instead, the ambassador

received a housing allowance from the State Department to pay for a building. Despite a tight housing market, Gerard

was able to find a palace on the Wilhelm Platz, across the street from the Chancellery and the Foreign Office. But the

structure was gutted and took several months to equip, at the cost of Gerard's first year's salary. The embassy staff

consisted of only four secretaries (Joseph C. Grew, Willing Spencer, Lanier Winslow, and Gerard's private secretary)

and two clerks. The American government's representatives in Germany were ill-prepared for the upcoming conflagration

that would overtax the embassy staff.6

Gerard accepted an important responsibility when he became the United States Ambassador to Germany in September 1913.

When he arrived in Berlin, he found the former ambassador's quarters inadequate for business needs. Unlike other

countries, the U.S. government did not own embassies abroad or even rent suitable buildings. Instead, the ambassador

received a housing allowance from the State Department to pay for a building. Despite a tight housing market, Gerard

was able to find a palace on the Wilhelm Platz, across the street from the Chancellery and the Foreign Office. But the

structure was gutted and took several months to equip, at the cost of Gerard's first year's salary. The embassy staff

consisted of only four secretaries (Joseph C. Grew, Willing Spencer, Lanier Winslow, and Gerard's private secretary)

and two clerks. The American government's representatives in Germany were ill-prepared for the upcoming conflagration

that would overtax the embassy staff.6

7

When the war began in August 1914, the embassy staff was quickly overwhelmed by the sudden demands of the wartime

emergency. Additional personnel arrived to augment the staff, including John R. Jackson, Barclay Rives, Lithgow Osborn,

Captain Walter Gheradi, Captain Herbster, Robert M. Scotten, Hugh Wilson, Rivington Pyne, Grafton Minot, and Charles

Russell. In addition, American volunteers in Germany, such as Boylston Beal and Ellis Dressel, absorbed some of the

office load. The first order of business was to help American citizens stranded in Germany and Switzerland get home.

The embassy set up an emergency relief committee to provide passports (Americans could travel around Europe before

the war without passports, but needed visas to transit through belligerent nations once the war began), money, and

railroad and steamship tickets through the Netherlands to get back to the United States.

When the war began in August 1914, the embassy staff was quickly overwhelmed by the sudden demands of the wartime

emergency. Additional personnel arrived to augment the staff, including John R. Jackson, Barclay Rives, Lithgow Osborn,

Captain Walter Gheradi, Captain Herbster, Robert M. Scotten, Hugh Wilson, Rivington Pyne, Grafton Minot, and Charles

Russell. In addition, American volunteers in Germany, such as Boylston Beal and Ellis Dressel, absorbed some of the

office load. The first order of business was to help American citizens stranded in Germany and Switzerland get home.

The embassy set up an emergency relief committee to provide passports (Americans could travel around Europe before

the war without passports, but needed visas to transit through belligerent nations once the war began), money, and

railroad and steamship tickets through the Netherlands to get back to the United States.

The embassy also took over British interests in Germany after Great Britain declared war in response to the invasion

of Belgium. Beal organized a special committee to supervise British interests, which was later taken over by Jackson

with the assistance of Russell and Osborne. This committee became responsible for representing the British government

concerning the disposition of property and the treatment of British subjects in the German Empire. The Americans

reported to the British government and transferred correspondence to German officials. The American embassy also took

on the interests of other foreign powers in Germany as they entered the war, including Japan, Serbia, Romania, and

mighty San Marino. The clerical work associated with these responsibilities mushroomed, further taxing the meager

resources of the American embassy.7

The embassy also took over British interests in Germany after Great Britain declared war in response to the invasion

of Belgium. Beal organized a special committee to supervise British interests, which was later taken over by Jackson

with the assistance of Russell and Osborne. This committee became responsible for representing the British government

concerning the disposition of property and the treatment of British subjects in the German Empire. The Americans

reported to the British government and transferred correspondence to German officials. The American embassy also took

on the interests of other foreign powers in Germany as they entered the war, including Japan, Serbia, Romania, and

mighty San Marino. The clerical work associated with these responsibilities mushroomed, further taxing the meager

resources of the American embassy.7

8

Once the initial crisis passed, Gerard found that his main responsibility was toward military and civilian prisoners

of war in Germany. Like all the major powers, the Germans were not prepared to care for thousands-and, within a year,

millions-of enemy soldiers. Sanitary, dietary, and housing conditions varied tremendously between prison camps. Although

the care and treatment of POWs were codified in international law under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the numbers

of prisoners and the variety of camps created a myriad of problems. Dressel joined the embassy staff early in the war to

take on POW work. As the numbers of war prisoners in Germany grew, however, the staff required to support this work

expanded.8

Once the initial crisis passed, Gerard found that his main responsibility was toward military and civilian prisoners

of war in Germany. Like all the major powers, the Germans were not prepared to care for thousands-and, within a year,

millions-of enemy soldiers. Sanitary, dietary, and housing conditions varied tremendously between prison camps. Although

the care and treatment of POWs were codified in international law under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the numbers

of prisoners and the variety of camps created a myriad of problems. Dressel joined the embassy staff early in the war to

take on POW work. As the numbers of war prisoners in Germany grew, however, the staff required to support this work

expanded.8

9

Serving the interests of Allied POWs in Germany was quite difficult from a bureaucratic perspective. Gerard lodged

complaints about war prison conditions with the German Foreign Office. Often, Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow

failed to respond, and Gerard directly contacted Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg. After several protests

and threats, von Bethmann-Hollweg authorized Gerard to contact the military staff directly regarding his concerns.

Before the war, the German Empire was divided into twenty-four military districts (Bezirke), which served as army

corps regions (this included one Württemberger, two Saxon, and three Bavarian corps). Every army corps9 had its own prison camp system, and under the German pre-war plan prisoners

captured by units of a particular army corps were sent to prisons under that corps' administration. Each corps commander

served as the military governor of the region and assumed dictatorial power over civil and military issues once war was

declared. They answered directly to the Minister of War, but basically had a great deal of autonomy. American

representatives had to deal directly with the corps commanders simply to get permission to visit prison camps under

their jurisdiction.10

Serving the interests of Allied POWs in Germany was quite difficult from a bureaucratic perspective. Gerard lodged

complaints about war prison conditions with the German Foreign Office. Often, Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow

failed to respond, and Gerard directly contacted Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg. After several protests

and threats, von Bethmann-Hollweg authorized Gerard to contact the military staff directly regarding his concerns.

Before the war, the German Empire was divided into twenty-four military districts (Bezirke), which served as army

corps regions (this included one Württemberger, two Saxon, and three Bavarian corps). Every army corps9 had its own prison camp system, and under the German pre-war plan prisoners

captured by units of a particular army corps were sent to prisons under that corps' administration. Each corps commander

served as the military governor of the region and assumed dictatorial power over civil and military issues once war was

declared. They answered directly to the Minister of War, but basically had a great deal of autonomy. American

representatives had to deal directly with the corps commanders simply to get permission to visit prison camps under

their jurisdiction.10

10

The magnitude of the task of inspecting POW camps increased almost exponentially during the war. The German offensive

in the West led to the capture of large numbers of British, French, and Belgian troops, so that by September 1914 the

Germans held over 285,000 prisoners. By March 1915, this number had grown to 654,000 POWs; it reached one million in

August, and expanded to 1.4 million men by the end of the year. Military offensives against Russia and in the Balkans

further taxed the German POW system, and by December 1916 the Germans were caring for 1.8 million prisoners of war. By

the time of the Armistice, in November 1918, the Germans held 2.8 million Allied prisoners, in 164 primary, or "parent"

(Stammlager), prison camps including seventy-five officers' camps and eighty-nine enlisted men's camps across the German Empire.

By far the majority of the prisoners held by the Germans were Russians (59 percent), followed by French (22 percent),

and British prisoners (almost 8 percent). The remaining 12 percent of Germany's prison population included Belgians,

Serbs, Romanians, Italians, Portuguese, Japanese, Americans, Montenegrins, Greeks, Brazilians, and Panamanians. This

extensive POW system was supervised by the Prisoner of War Commission of the Ministry of War. At the beginning of the

war, this department was commanded by Colonel Friedrich, who rose to the rank of major general as his duties multiplied. To

guard these POWs, the Germans had to assign over three hundred thousand troops, which depleted the number of men available for combat

operations and workers in the factories. In addition, the Ministries of War in Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg

administered their own prisoner-of-war departments within their kingdoms.11

The magnitude of the task of inspecting POW camps increased almost exponentially during the war. The German offensive

in the West led to the capture of large numbers of British, French, and Belgian troops, so that by September 1914 the

Germans held over 285,000 prisoners. By March 1915, this number had grown to 654,000 POWs; it reached one million in

August, and expanded to 1.4 million men by the end of the year. Military offensives against Russia and in the Balkans

further taxed the German POW system, and by December 1916 the Germans were caring for 1.8 million prisoners of war. By

the time of the Armistice, in November 1918, the Germans held 2.8 million Allied prisoners, in 164 primary, or "parent"

(Stammlager), prison camps including seventy-five officers' camps and eighty-nine enlisted men's camps across the German Empire.

By far the majority of the prisoners held by the Germans were Russians (59 percent), followed by French (22 percent),

and British prisoners (almost 8 percent). The remaining 12 percent of Germany's prison population included Belgians,

Serbs, Romanians, Italians, Portuguese, Japanese, Americans, Montenegrins, Greeks, Brazilians, and Panamanians. This

extensive POW system was supervised by the Prisoner of War Commission of the Ministry of War. At the beginning of the

war, this department was commanded by Colonel Friedrich, who rose to the rank of major general as his duties multiplied. To

guard these POWs, the Germans had to assign over three hundred thousand troops, which depleted the number of men available for combat

operations and workers in the factories. In addition, the Ministries of War in Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg

administered their own prisoner-of-war departments within their kingdoms.11

11

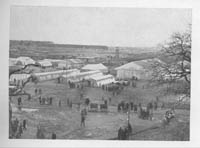

The Germans developed a wide range of different kinds of prison camps, many with specific functions. The most common

type of prison facility was the POW camp for enlisted men, where captured soldiers were sent under the command of

non-commissioned officers. The Germans established a large number of officer prison camps, but their populations were

much smaller than enlisted men's camps. Prisoners wounded in combat or who became ill were sent to special military

hospitals, especially if their conditions were not acute. The Germans sent enemy nationals who threatened security to

civilian internment camps. There were also special function camps. In response to Allied atrocities, and as one of the

few means to modify enemy policies, the Germans sometimes sent POWs to reprisal camps, where the prisoners endured the

loss of privileges or poor conditions. To persuade potentially sympathetic Allied POWs to support the German cause, the

Germans established propaganda camps. These camps represented the other extreme from reprisal camps. POWs at the latter

facilities enjoyed extra rations, superior quarters, and extra privileges to sway their loyalty. Finally, the Germans

formed labor detachments, where POWs left prison camps and took employment in factories or fields. The prisoners escaped

the monotony of prison life and earned a steady income, while the Germans used unproductive manpower to support the

national economy.12

The Germans developed a wide range of different kinds of prison camps, many with specific functions. The most common

type of prison facility was the POW camp for enlisted men, where captured soldiers were sent under the command of

non-commissioned officers. The Germans established a large number of officer prison camps, but their populations were

much smaller than enlisted men's camps. Prisoners wounded in combat or who became ill were sent to special military

hospitals, especially if their conditions were not acute. The Germans sent enemy nationals who threatened security to

civilian internment camps. There were also special function camps. In response to Allied atrocities, and as one of the

few means to modify enemy policies, the Germans sometimes sent POWs to reprisal camps, where the prisoners endured the

loss of privileges or poor conditions. To persuade potentially sympathetic Allied POWs to support the German cause, the

Germans established propaganda camps. These camps represented the other extreme from reprisal camps. POWs at the latter

facilities enjoyed extra rations, superior quarters, and extra privileges to sway their loyalty. Finally, the Germans

formed labor detachments, where POWs left prison camps and took employment in factories or fields. The prisoners escaped

the monotony of prison life and earned a steady income, while the Germans used unproductive manpower to support the

national economy.12

12

Gerard conducted his first inspection of a POW camp at Döberitz (Brandenburg, Prussia) on 20 August 1914,

considering such visits to be the best means to determine the conditions in camps. The ambassador and his staff then

sent reports to Washington and London. Investigations conducted by Parliament were based on these reports and led to

the publication of a series of White Papers. Gerard's inspections raised important diplomatic questions. The legal

question of the inspection of POW camps by neutral powers, along with the rights of diplomatic representatives charged

with the interests of belligerents, were not well defined under international law.

Gerard conducted his first inspection of a POW camp at Döberitz (Brandenburg, Prussia) on 20 August 1914,

considering such visits to be the best means to determine the conditions in camps. The ambassador and his staff then

sent reports to Washington and London. Investigations conducted by Parliament were based on these reports and led to

the publication of a series of White Papers. Gerard's inspections raised important diplomatic questions. The legal

question of the inspection of POW camps by neutral powers, along with the rights of diplomatic representatives charged

with the interests of belligerents, were not well defined under international law.

The Germans became irritated about these reports and protested Gerard's actions to the Department of State. Secretary

of State William Jennings Bryan, ever fearful of a confrontation with the belligerents that could pull the United

States into the war, instructed Gerard to end these official visits. Gerard, however, responded that the State

Department should give up any notion of protecting British interests since it was plainly his duty to conduct the

investigations. As a result, the State Department countermanded the original order and allowed Gerard to continue

his activities.13

The Germans became irritated about these reports and protested Gerard's actions to the Department of State. Secretary

of State William Jennings Bryan, ever fearful of a confrontation with the belligerents that could pull the United

States into the war, instructed Gerard to end these official visits. Gerard, however, responded that the State

Department should give up any notion of protecting British interests since it was plainly his duty to conduct the

investigations. As a result, the State Department countermanded the original order and allowed Gerard to continue

his activities.13

13

POW diplomacy became a contentious issue for a number of reasons. While the Hague Conventions spelled out the

responsibilities of neutral powers to ensure the welfare of war prisoners, the specific details regarding the mechanics

of such activities remained unclear. To determine prisoner conditions, embassy officials had to visit prison camps,

inspect facilities, and discuss conditions with the prisoners. This was a very delicate situation. Camp commandants

resented "outside" interference by neutral officials in the operation of their camps, and feared recrimination from

superiors if their camps were found to be unsatisfactory. On the other hand, if conditions were found to be too lenient,

they could be accused of abetting the enemy. Neutral visits also had the potential for disrupting the prison population

by giving POWs the idea that they could demand greater concessions from a country committed to total war. From the

popular perspective, citizens in every belligerent country, both in the Allied and Central Powers, believed that their

captured troops suffered in captivity, while enemy soldiers under their nation's care received the best of treatment.

Reports of atrocities in enemy prison camps led to acrimonious accusations of barbarity between belligerent governments

which stirred up public opinion and made neutral diplomatic activity much more difficult. The only solution to this

dilemma was the introduction of inspections by neutral officials in all belligerent countries. Yet inspection alone

was not sufficient to address the problems found in prison camps. Neutral officials also had to have the power to

distribute clothing, food, medical supplies, and money to improve poor conditions. Belligerent governments were reluctant

to grant such powers unless they were assured that their troops would receive the same amenities in enemy prison camps.

This resulted in the Principle of Reciprocity, whereby American officials negotiated with belligerent governments to

gain permission to inspect camps and administer to POWs, with the understanding that countries on the other side would

grant similar powers to American officials there, so that each countries' imprisoned troops would receive the same

benefits.14

POW diplomacy became a contentious issue for a number of reasons. While the Hague Conventions spelled out the

responsibilities of neutral powers to ensure the welfare of war prisoners, the specific details regarding the mechanics

of such activities remained unclear. To determine prisoner conditions, embassy officials had to visit prison camps,

inspect facilities, and discuss conditions with the prisoners. This was a very delicate situation. Camp commandants

resented "outside" interference by neutral officials in the operation of their camps, and feared recrimination from

superiors if their camps were found to be unsatisfactory. On the other hand, if conditions were found to be too lenient,

they could be accused of abetting the enemy. Neutral visits also had the potential for disrupting the prison population

by giving POWs the idea that they could demand greater concessions from a country committed to total war. From the

popular perspective, citizens in every belligerent country, both in the Allied and Central Powers, believed that their

captured troops suffered in captivity, while enemy soldiers under their nation's care received the best of treatment.

Reports of atrocities in enemy prison camps led to acrimonious accusations of barbarity between belligerent governments

which stirred up public opinion and made neutral diplomatic activity much more difficult. The only solution to this

dilemma was the introduction of inspections by neutral officials in all belligerent countries. Yet inspection alone

was not sufficient to address the problems found in prison camps. Neutral officials also had to have the power to

distribute clothing, food, medical supplies, and money to improve poor conditions. Belligerent governments were reluctant

to grant such powers unless they were assured that their troops would receive the same amenities in enemy prison camps.

This resulted in the Principle of Reciprocity, whereby American officials negotiated with belligerent governments to

gain permission to inspect camps and administer to POWs, with the understanding that countries on the other side would

grant similar powers to American officials there, so that each countries' imprisoned troops would receive the same

benefits.14

14

The break in the diplomatic log-jam began in November 1914. A large number of reports of poor treatment of German

POWs in England inflamed German public opinion. Gerard arranged with the British government, through U.S. Ambassador

Walter Hines Page, for Jackson to visit prison camps in England. In return, Chandler Anderson of the American embassy

in London was to conduct a similar tour of German prison camps and report to the British government. During the winter,

Jackson inspected the situation and provided a report that allayed the fears of ill treatment of Germans under British

care. With the support of the Wilson Administration and greater German public sympathy, Gerard arranged a meeting in

March 1915 between the German Foreign Office, the Ministry of War, and the General Staff to implement an inspection

plan for American officials.

The break in the diplomatic log-jam began in November 1914. A large number of reports of poor treatment of German

POWs in England inflamed German public opinion. Gerard arranged with the British government, through U.S. Ambassador

Walter Hines Page, for Jackson to visit prison camps in England. In return, Chandler Anderson of the American embassy

in London was to conduct a similar tour of German prison camps and report to the British government. During the winter,

Jackson inspected the situation and provided a report that allayed the fears of ill treatment of Germans under British

care. With the support of the Wilson Administration and greater German public sympathy, Gerard arranged a meeting in

March 1915 between the German Foreign Office, the Ministry of War, and the General Staff to implement an inspection

plan for American officials.

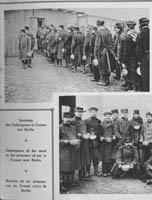

The Germans agreed to allow Gerard and ten U.S. embassy staff members to visit prison camps after reasonable notice

(twenty-four hours where possible) and permit American representatives to converse with prisoners within sight, but

out of hearing, of camp officials. Complaints were to be brought to camp commandants to be rectified before presenting

them to higher authorities. American embassy officials also received permission to distribute money to needy prisoners

through a fund established by the British government. Embassy officials, however, did not receive permission to

distribute food or clothing to POWs, although the German government agreed to allow prisoners to receive packages from

home containing such material. The Germans accepted the plan because their Foreign Office was making similar demands on

American personnel in France, Great Britain, and Russia to look after the interests of German prisoners incarcerated by

the Allies. This agreement was ratified by both the British and German governments, and gave American diplomatic staff

the authorization they needed to conduct investigations.15

The Germans agreed to allow Gerard and ten U.S. embassy staff members to visit prison camps after reasonable notice

(twenty-four hours where possible) and permit American representatives to converse with prisoners within sight, but

out of hearing, of camp officials. Complaints were to be brought to camp commandants to be rectified before presenting

them to higher authorities. American embassy officials also received permission to distribute money to needy prisoners

through a fund established by the British government. Embassy officials, however, did not receive permission to

distribute food or clothing to POWs, although the German government agreed to allow prisoners to receive packages from

home containing such material. The Germans accepted the plan because their Foreign Office was making similar demands on

American personnel in France, Great Britain, and Russia to look after the interests of German prisoners incarcerated by

the Allies. This agreement was ratified by both the British and German governments, and gave American diplomatic staff

the authorization they needed to conduct investigations.15

15

Eventually, Gerard assembled a professional POW inspection staff. Dr. Karl Ohnesorg, a U.S. Navy surgeon, supervised

the medical staff at the embassy, which included Doctors Daniel J. McCarthy, Alonzo Taylor and Jerome Webster. They

were responsible for investigating the sanitary and dietary conditions at German prison camps, assisted by other

members of the embassy staff, including Jackson, Grew, Winslow, Osborn, Rives, and Beal. In Bavaria, Archdeacon Niles

of the American Episcopal Church visited prison camps in that kingdom. Despite the increase in manpower required to

look after Allied interests in Germany, the U.S. embassy staff was still overwhelmed by the clerical work. American

personnel processed all of the complaints issued by the German government regarding the treatment of German prisoners

in Allied hands, as well as protests from Allied countries about the treatment of Allied POWs in Germany. This was a

major undertaking, one for which the United States government lacked the requisite social welfare expertise and

personnel.16

Eventually, Gerard assembled a professional POW inspection staff. Dr. Karl Ohnesorg, a U.S. Navy surgeon, supervised

the medical staff at the embassy, which included Doctors Daniel J. McCarthy, Alonzo Taylor and Jerome Webster. They

were responsible for investigating the sanitary and dietary conditions at German prison camps, assisted by other

members of the embassy staff, including Jackson, Grew, Winslow, Osborn, Rives, and Beal. In Bavaria, Archdeacon Niles

of the American Episcopal Church visited prison camps in that kingdom. Despite the increase in manpower required to

look after Allied interests in Germany, the U.S. embassy staff was still overwhelmed by the clerical work. American

personnel processed all of the complaints issued by the German government regarding the treatment of German prisoners

in Allied hands, as well as protests from Allied countries about the treatment of Allied POWs in Germany. This was a

major undertaking, one for which the United States government lacked the requisite social welfare expertise and

personnel.16

16

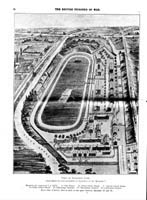

Gerard faced many different types of problems as a neutral prison camp inspector. When the war began in August

1914, approximately fifty thousand German subjects of military age were in England engaged in study, business, or tourism.

However, there were only eight thousand British subjects in Germany. These men enjoyed considerable liberty at the beginning

of the war, being required only to check in at police stations on a periodic basis. Talks began between the British

and German governments about the exchange of civilians. The British insisted on a one-for-one ratio of exchange,

while the Germans sought a complete exchange of all enemy nationals. Since the Germans would obtain almost a full

army corps as a result of the German formula, the British declined and the talks collapsed. In the autumn of 1914,

the British decided to imprison German nationals in the British Isles, and in reprisal the Germans interned English

civilians at the horse racetrack at Ruhleben in Prussia, outside of Berlin. Only after several years did Gerard

succeed in resuscitating the talks. The British and German governments agreed to an exchange of all civilians past

military age (forty-five years old) in the summer of 1916. British civilians of military age remained in German prison

camps, however, until the end of the war. An agreement between the French and German governments was signed

late in 1917.17

Gerard faced many different types of problems as a neutral prison camp inspector. When the war began in August

1914, approximately fifty thousand German subjects of military age were in England engaged in study, business, or tourism.

However, there were only eight thousand British subjects in Germany. These men enjoyed considerable liberty at the beginning

of the war, being required only to check in at police stations on a periodic basis. Talks began between the British

and German governments about the exchange of civilians. The British insisted on a one-for-one ratio of exchange,

while the Germans sought a complete exchange of all enemy nationals. Since the Germans would obtain almost a full

army corps as a result of the German formula, the British declined and the talks collapsed. In the autumn of 1914,

the British decided to imprison German nationals in the British Isles, and in reprisal the Germans interned English

civilians at the horse racetrack at Ruhleben in Prussia, outside of Berlin. Only after several years did Gerard

succeed in resuscitating the talks. The British and German governments agreed to an exchange of all civilians past

military age (forty-five years old) in the summer of 1916. British civilians of military age remained in German prison

camps, however, until the end of the war. An agreement between the French and German governments was signed

late in 1917.17

17 The American ambassador was more successful in securing the safe transit of Japanese subjects out of Germany. In early August 1914, the Japanese government warned its nationals that a break in relations with Germany was possible. The Germans had hoped that the Japanese would enter the war on the side of the Central Powers. When the Japanese declared war against Germany on August 23, seeking control of German colonial possessions in the Far East and in the Pacific, German public opinion turned against the Japanese. To protect Japanese nationals as well as keep them under surveillance, the Germans interned Japanese subjects at Ruhleben. Gerard negotiated the release and departure of these people from Germany, and Winslow accompanied them through Switzerland.18

18 Two years into the war, the British and German governments agreed to the exchange of debilitated officers and men through Switzerland, which improved conditions for seriously sick and wounded POWs. The British and German governments signed an exchange agreement regarding severely wounded and disabled POWs on 2 June 1917. The French and German governments signed similar treaties on 15 March and 15 May 1918. Members of the Swiss Commission visited prison camps and hospitals in Germany, Britain, and France, and selected suitable candidates for exchange. These men had suffered serious wounds (usually the loss of limbs, sight, or head wounds) or crippling diseases (advanced tuberculosis) that ended their military careers. Upon arrival in Switzerland, they went to hospitals and sanitariums for recuperation or received physical therapy to learn new trades and skills. The change of food and scenery and potential reunion with their families substantially aided their recovery. Under this agreement, severely wounded POWs would eventually be repatriated. Despite serious problems with this exchange system (including the number of patients accepted by the Swiss Commission, and inconsistent conditions across recovery facilities), the program saved the lives of many Allied POWs. The German and Russian governments drafted a similar exchange agreement, using Sweden as the conduit for exchanging wounded and sick prisoners.19

19

Relations between the American embassy inspectors and the German military were not always smooth. German officials

often took exception to critical American reports. In July 1916, the Americans reported the shooting of the second

Irish POW at the propaganda prison camp at Limburg-am-Lahn in Prussia. The Germans became quite upset, and threatened

to restrict American access to war prisoners by denying them private conversations. Later that month, the Germans

followed through on this threat after the visit of a Russian noblewoman to a POW camp resulted in a riot.

Gerard concluded that the Germans had a lot to conceal regarding conditions in the prison camps, and that the Germans

had used the disturbance in the prison compound as a pretext to limit neutral contact with POWs.20

Relations between the American embassy inspectors and the German military were not always smooth. German officials

often took exception to critical American reports. In July 1916, the Americans reported the shooting of the second

Irish POW at the propaganda prison camp at Limburg-am-Lahn in Prussia. The Germans became quite upset, and threatened

to restrict American access to war prisoners by denying them private conversations. Later that month, the Germans

followed through on this threat after the visit of a Russian noblewoman to a POW camp resulted in a riot.

Gerard concluded that the Germans had a lot to conceal regarding conditions in the prison camps, and that the Germans

had used the disturbance in the prison compound as a pretext to limit neutral contact with POWs.20

20

20

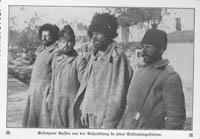

The American embassy investigated a plethora of protests and complaints in German prison camps, such as the lack of

adequate clothing for British soldiers. They arrived from the Western Front in summer fatigues in August and September,

and were not prepared for the approaching winter. The Americans purchased heavy underwear and other clothes for these

men and began to stockpile clothing for British prisoners in a warehouse in Berlin. But the Germans refused to permit

the American embassy staff to distribute the clothing because, under the Hague Conventions, they were responsible for

providing uniforms to their captives. As a result, the clothing was not issued until well into the winter. A related

issue was the transportation of British prisoners from the front to prison camps in Germany. The British asked American

inspectors to monitor POW treatment during prisoner movements in terms of rations issued, crowded accommodations, and

speed of transit.21

The American embassy investigated a plethora of protests and complaints in German prison camps, such as the lack of

adequate clothing for British soldiers. They arrived from the Western Front in summer fatigues in August and September,

and were not prepared for the approaching winter. The Americans purchased heavy underwear and other clothes for these

men and began to stockpile clothing for British prisoners in a warehouse in Berlin. But the Germans refused to permit

the American embassy staff to distribute the clothing because, under the Hague Conventions, they were responsible for

providing uniforms to their captives. As a result, the clothing was not issued until well into the winter. A related

issue was the transportation of British prisoners from the front to prison camps in Germany. The British asked American

inspectors to monitor POW treatment during prisoner movements in terms of rations issued, crowded accommodations, and

speed of transit.21

21 These issues paled in comparison, however, to those surrounding the daily rations provided to POWs. Under the Hague Convention, war prisoners were to receive the same rations as a nation's troops. But the Allies imposed a strict blockade on the Central Powers, including the transportation of foodstuffs, and as the war progressed, the Germans captured large numbers of Allied POWs while facing declining food supplies. The Allied blockade severely diminished food availability in Germany, and the German government had to ration most food products by the end of 1915. Meat and dairy products disappeared, tropical fruits vanished, and food substitutes appeared on grocers' shelves. The Germans faced famine during the Kohlrubenwinter (Turnip Winter) of 1916-1917. The government gave food priority to troops and workers in the war industries; other civilians received reduced rations, and POWs had to get by on yet more meager fare. German scientists designed a survival diet based on just enough caloric content to keep prisoners' body and spirit together, with little to spare. Doctors from the American embassy inspected prison rations closely, and often challenged German calculations regarding minimum caloric intake. British and French prisoners survived primarily because their governments, as well as their families and friends, sent parcels of food or shipments of bread from neutral countries, primarily Denmark and Switzerland. These food parcels made a major difference in the survival of POWs from Western Allied nations. The condition of Russian, Romanian, and Serbian prisoners was far more bleak. The elimination of Serbia as an independent kingdom by December 1915 ended any chance of relief from home. Disorganization in Russia and Romania prevented these governments from sending supplies to their men held in Germany. By July 1916, Gerard realized that Russian prisoners were slowly dying of starvation. Because the U.S. government was responsible for Romanian interests in Germany, Gerard ordered American officials to report the poor dietary conditions Romanian and Serbian prisoners endured. All the American embassy could do was encourage the Germans to increase their rations, although they realized that such a change in policy was impossible. When the Germans signed the Armistice in November 1918, the German population was facing mass starvation. According to the German Health Office, by December 1918, 763,000 Germans died from starvation, malnutrition, or diseases attributable to the Allied blockade.22

22

One way to solve the problem of feeding idle prisoners was to put them to work, especially in agricultural production.

Under the terms of the Hague Conventions, enlisted men held as POWs were required to work, while non-commissioned officers

and officers had the option of working. Under these treaties, prisoners could not be forced to work in war-related

industries or in unsafe conditions (requirements that were broken by the Central Powers and Allies alike). Despite

these violations of international law, prisoners generally preferred labor to the monotony of prison camps.

One way to solve the problem of feeding idle prisoners was to put them to work, especially in agricultural production.

Under the terms of the Hague Conventions, enlisted men held as POWs were required to work, while non-commissioned officers

and officers had the option of working. Under these treaties, prisoners could not be forced to work in war-related

industries or in unsafe conditions (requirements that were broken by the Central Powers and Allies alike). Despite

these violations of international law, prisoners generally preferred labor to the monotony of prison camps.

Prisoners participated in a wide range of activities, including mining, farming, forestry, quarry work, road construction,

factory work, railroad construction, and shipping. In 1915, Germany employed only a small number of POWs, but by December

1916 over 1.1 million civilian and military prisoners were at work (340,000 worked in industry and trade, while the vast

majority-630,000-worked in agricultural production). Gerard estimated that the Germans employed two million POW laborers

by February 1917. The employment of POWs aided both the Germans and the prisoners. For the Germans, prisoners replaced

workers drafted by the army and solved a potential labor shortage. For the prisoners, the daily wage (ranging from sixteen to thirty

Pfennigs per day for farm labor, to thirty to fifty Pfennigs for small industry work, to two to three Marks per day for highly skilled labor)

could be used to augment their meager rations. POWs on farms had direct access to foodstuffs and well-stocked larders.

Prisoners participated in a wide range of activities, including mining, farming, forestry, quarry work, road construction,

factory work, railroad construction, and shipping. In 1915, Germany employed only a small number of POWs, but by December

1916 over 1.1 million civilian and military prisoners were at work (340,000 worked in industry and trade, while the vast

majority-630,000-worked in agricultural production). Gerard estimated that the Germans employed two million POW laborers

by February 1917. The employment of POWs aided both the Germans and the prisoners. For the Germans, prisoners replaced

workers drafted by the army and solved a potential labor shortage. For the prisoners, the daily wage (ranging from sixteen to thirty

Pfennigs per day for farm labor, to thirty to fifty Pfennigs for small industry work, to two to three Marks per day for highly skilled labor)

could be used to augment their meager rations. POWs on farms had direct access to foodstuffs and well-stocked larders.

In addition, by working on farms and in small factories, both Germans and POWs saw the human side of their enemies.

Gerard recognized that war prisoners enjoyed a higher standard of living when employed outside of camps. But he

deplored the ill-gotten gains by the Junkers who now reaped large profits by charging wartime prices for food

produced by poorly-paid POW labor. The American embassy often inspected labor problems, such as British POWs working

in sewage farms (which led to an official American protest and a German recall of the workers) and as stevedores in

Libau (a practice that was approved by Jackson). The Americans could not investigate all cases of labor abuse, since

the forced employment of French, Belgian, and Polish civilian labor was outside the purview of their

jurisdiction.23

In addition, by working on farms and in small factories, both Germans and POWs saw the human side of their enemies.

Gerard recognized that war prisoners enjoyed a higher standard of living when employed outside of camps. But he

deplored the ill-gotten gains by the Junkers who now reaped large profits by charging wartime prices for food

produced by poorly-paid POW labor. The American embassy often inspected labor problems, such as British POWs working

in sewage farms (which led to an official American protest and a German recall of the workers) and as stevedores in

Libau (a practice that was approved by Jackson). The Americans could not investigate all cases of labor abuse, since

the forced employment of French, Belgian, and Polish civilian labor was outside the purview of their

jurisdiction.23

23

One of the greatest threats to POWs in captivity was contagious disease, which often became epidemic in prison camps.

The Germans and the Western Allies disagreed on the German practice of integrating various nationalities in the same

prison camp. The Western Allies demanded that their troops be housed in separate facilities, segregated from Russian

and Serbian prisoners.

One of the greatest threats to POWs in captivity was contagious disease, which often became epidemic in prison camps.

The Germans and the Western Allies disagreed on the German practice of integrating various nationalities in the same

prison camp. The Western Allies demanded that their troops be housed in separate facilities, segregated from Russian

and Serbian prisoners.

The Germans replied that the Allies should get to know each other, and mixed the nationalities together. This led to

considerable friction within prison populations, but the greatest threat was medical. Russian sanitary practices were

far behind Western standards, and Russian troops with mild cases of various infectious diseases were often mobilized

by the Tsarist Army.

The Germans replied that the Allies should get to know each other, and mixed the nationalities together. This led to

considerable friction within prison populations, but the greatest threat was medical. Russian sanitary practices were

far behind Western standards, and Russian troops with mild cases of various infectious diseases were often mobilized

by the Tsarist Army.

In addition, Russian medical officers treated the outbreaks in the German prisons, but their training was inferior to

that of Western Allied medical officers. As a result, numerous outbreaks of disease developed in prison camps, with

devastating results. Deadly epidemics that ravaged German prison camps included dysentery, influenza (grippe), petechial

fever, typhoid fever (enteric fever), cholera, tuberculosis, and typhus.

In addition, Russian medical officers treated the outbreaks in the German prisons, but their training was inferior to

that of Western Allied medical officers. As a result, numerous outbreaks of disease developed in prison camps, with

devastating results. Deadly epidemics that ravaged German prison camps included dysentery, influenza (grippe), petechial

fever, typhoid fever (enteric fever), cholera, tuberculosis, and typhus.

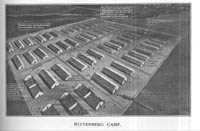

24

Early in the war, with the huge influx of Allied POWs, epidemics became a major sanitary issue. In November 1914, a

devastating typhus epidemic broke out among the Russian prisoners at Wittenberg, in Prussian Saxony. To contain the

outbreak, the Germans withdrew their guards from the interior of the camp and strictly quarantined the inmates. The

Germans assigned six captured British medical officers to the facility, and they discovered horrific conditions. Among

their findings were insufficient medical supplies and meager rations, no sanitation organization to isolate infected

POWs, and little support from the German government. Three of the British medical officers died of typhus, and a fourth

contracted the disease but recovered. By April 1915, with the arrival of warm weather and better medical supplies, the

epidemic had run its course. The British public deplored the "horrors of Wittenberg" and demanded action. The Germans

prevented American diplomatic officials from visiting the camp until October 1915, and Gerard personally inspected the

camp in November. Typhus epidemics broke out in other German prison camps as well. In February 1915, a typhus outbreak

at Gardelegen, also in Prussian Saxony, resulted in two thousand sick POWs by June. Of these patients, approximately three hundred, or

15 percent, died. Typhus epidemics also broke out across Germany, in camps at Schneidemühl, Stendal, Brandenburg, Altdamm,

Cassel, Chemnitz, Langensalza, Sagan, Zerbst, and Zossen.24

Early in the war, with the huge influx of Allied POWs, epidemics became a major sanitary issue. In November 1914, a

devastating typhus epidemic broke out among the Russian prisoners at Wittenberg, in Prussian Saxony. To contain the

outbreak, the Germans withdrew their guards from the interior of the camp and strictly quarantined the inmates. The

Germans assigned six captured British medical officers to the facility, and they discovered horrific conditions. Among

their findings were insufficient medical supplies and meager rations, no sanitation organization to isolate infected

POWs, and little support from the German government. Three of the British medical officers died of typhus, and a fourth

contracted the disease but recovered. By April 1915, with the arrival of warm weather and better medical supplies, the

epidemic had run its course. The British public deplored the "horrors of Wittenberg" and demanded action. The Germans

prevented American diplomatic officials from visiting the camp until October 1915, and Gerard personally inspected the

camp in November. Typhus epidemics broke out in other German prison camps as well. In February 1915, a typhus outbreak

at Gardelegen, also in Prussian Saxony, resulted in two thousand sick POWs by June. Of these patients, approximately three hundred, or

15 percent, died. Typhus epidemics also broke out across Germany, in camps at Schneidemühl, Stendal, Brandenburg, Altdamm,

Cassel, Chemnitz, Langensalza, Sagan, Zerbst, and Zossen.24

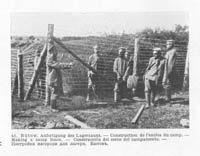

25 Allied protests and neutral inspections prompted the Germans to improve the sanitary conditions in POW camps radically. New prison camps were designed to arrest epidemics before they emerged. At Limburg-am-Lahn, an American embassy attaché reported excellent sanitary conditions in the camp. German medical authorities set up sanitary regulations for the POW system based on scientific principles. The first step was to clean the bodies and clothes of incoming POWs. Newly arrived prisoners reported first to the prison showers and delousing station. POWs surrendered all of their clothing for fumigation and hot steam treatment, passed through showers or baths, had their heads shaved to eliminate any remaining lice, and reported for an inspection by a doctor. Camp authorities set up quarantine stations near the disinfection facilities so that large numbers of POWs could be immediately separated from the main prison population if a contagious disease was detected. The hospital had a staff of five German doctors. An inspecting American attaché found few patients and his report reflected favorably on the health of the POWs. The next step was to maintain the health of the inmates. Camp officials organized a sanitary corps of POWs to maintain the hygiene and cleanliness of the camp. All prisoners were required to shower or bathe at least twice a week, and could usually bathe more often if they desired. The Germans constructed new barracks designed to improve ventilation, since sealed buildings promoted the spread of airborne diseases. Prisoners also participated in military drill, calisthenics, and gymnastic exercises under the orders of their own non-commissioned officers to keep physically fit. In addition, German doctors made rounds through the barracks every morning so prisoners could report for sick call.25

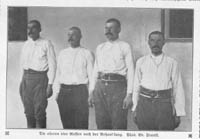

26

In May 1915, U.S. Senator Albert Beveridge conducted an extensive tour of Germany, visiting army training centers, military

hospitals, and POW camps. He enjoyed private conversations with prisoners through an interpreter who had traveled with him

from his hometown, which avoided any possibility of German partiality. After inspecting several camps, he praised German

efforts on behalf of POWs. He found that general orders governed the administration of all of the camps, that prisoners

enjoyed the same quality and quantity of food as German soldiers (at this time, rations had been seriously affected by the

Allied blockade), and that POW barracks surpassed conditions for interned Belgian troops in Holland. He also noted that of

the thousands of prisoners that he met, all but one appeared to be in robust health. He was impressed by their general

physical fitness and approved of the Germans' plan to expand the employment of POWs outside of the prison camps to ease

their confinement and keep them physically fit.26

In May 1915, U.S. Senator Albert Beveridge conducted an extensive tour of Germany, visiting army training centers, military

hospitals, and POW camps. He enjoyed private conversations with prisoners through an interpreter who had traveled with him

from his hometown, which avoided any possibility of German partiality. After inspecting several camps, he praised German

efforts on behalf of POWs. He found that general orders governed the administration of all of the camps, that prisoners

enjoyed the same quality and quantity of food as German soldiers (at this time, rations had been seriously affected by the

Allied blockade), and that POW barracks surpassed conditions for interned Belgian troops in Holland. He also noted that of

the thousands of prisoners that he met, all but one appeared to be in robust health. He was impressed by their general

physical fitness and approved of the Germans' plan to expand the employment of POWs outside of the prison camps to ease

their confinement and keep them physically fit.26

27

In the final analysis, the Germans were neither saints nor sinners in their treatment of Allied prisoners. Allied accusations

that the Germans were conducting systematic murder and torture against POWs were clearly exaggerated. Epidemics in prison

camps in late 1914 and early 1915 killed large numbers of prisoners, and the German medical response, especially in the case

of Wittenberg, was one of confusion and fear. None of the belligerent powers had anticipated the number of prisoners that

they would have to care for during the war, or were in any way prepared for an extensive POW system. German military

authorities were unprepared at the beginning of the war to feed, shelter, and care for the huge numbers of Allied POWs.

In the final analysis, the Germans were neither saints nor sinners in their treatment of Allied prisoners. Allied accusations

that the Germans were conducting systematic murder and torture against POWs were clearly exaggerated. Epidemics in prison

camps in late 1914 and early 1915 killed large numbers of prisoners, and the German medical response, especially in the case

of Wittenberg, was one of confusion and fear. None of the belligerent powers had anticipated the number of prisoners that

they would have to care for during the war, or were in any way prepared for an extensive POW system. German military

authorities were unprepared at the beginning of the war to feed, shelter, and care for the huge numbers of Allied POWs.

In addition, despite the scientific approach the Germans took towards health standards, medical research was only beginning

to reveal the association between filth and vermin in the transmission of disease. In the case of typhus, researchers had

not yet discovered its cause, and concentrated instead on its treatment. Conditions also varied considerably between camps

as a result of the administrative abilities and humanitarian concerns of individual prison camp commanders. Some commandants

took a deep interest in the welfare of their charges, while others were derelict in their duty. Finally, the Allied blockade,

which significantly reduced the rations provided to POWs, had a particularly detrimental impact on the physical condition of

Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners. After American officials reported adversely on health conditions in prison camps,

the Germans focused on improving sanitary regulations. While there was a humanitarian motive behind this effort, the Germans

were also concerned about maintaining the physical well-being of POWs so they could be employed in the total war effort, and

in preventing epidemics from spreading into the civilian population.27

In addition, despite the scientific approach the Germans took towards health standards, medical research was only beginning

to reveal the association between filth and vermin in the transmission of disease. In the case of typhus, researchers had

not yet discovered its cause, and concentrated instead on its treatment. Conditions also varied considerably between camps

as a result of the administrative abilities and humanitarian concerns of individual prison camp commanders. Some commandants

took a deep interest in the welfare of their charges, while others were derelict in their duty. Finally, the Allied blockade,

which significantly reduced the rations provided to POWs, had a particularly detrimental impact on the physical condition of

Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners. After American officials reported adversely on health conditions in prison camps,

the Germans focused on improving sanitary regulations. While there was a humanitarian motive behind this effort, the Germans

were also concerned about maintaining the physical well-being of POWs so they could be employed in the total war effort, and

in preventing epidemics from spreading into the civilian population.27

28

According to statistics complied by Richard Speed, German prison camps were rigorous, but not overly harsh. Contemporary

critics of the German prison system focused on typhus epidemics, but of the 2.5 million prisoners held by Germany during

the war, while 118,000 POWs contracted this disease, only 1,060 died (less than one percent of those stricken). Of all

the Allied POW deaths in German prison camps, 89 percent were due to illness, most from either pneumonia or tuberculosis

(approximately sixty thousand, which represents 48 percent of total deaths). In addition, the death rate from sickness in Germany

varied tremendously between nationalities. The death rate among Western Allied prisoners was less than 2.5 percent (the

American rate was .73 percent, the Belgian 1.90 percent, the British 2.08 percent, and the French rate was 2.41 percent).

According to statistics complied by Richard Speed, German prison camps were rigorous, but not overly harsh. Contemporary

critics of the German prison system focused on typhus epidemics, but of the 2.5 million prisoners held by Germany during

the war, while 118,000 POWs contracted this disease, only 1,060 died (less than one percent of those stricken). Of all

the Allied POW deaths in German prison camps, 89 percent were due to illness, most from either pneumonia or tuberculosis

(approximately sixty thousand, which represents 48 percent of total deaths). In addition, the death rate from sickness in Germany

varied tremendously between nationalities. The death rate among Western Allied prisoners was less than 2.5 percent (the

American rate was .73 percent, the Belgian 1.90 percent, the British 2.08 percent, and the French rate was 2.41 percent).

Eastern Allied POWs died at a much higher rate: the Russian rate was 4.61 percent, the Italian 5.46 percent, the Serbian 5.81 percent, and the Romanian rate was an amazing 28.64 percent. Three factors explain this divergence: Western prisoners were generally in better health than their Eastern counterparts; Western POWs also arrived in prison camps clad in warmer and sturdier clothing; and, most importantly, Western prisoners had access to more food than Eastern POWs. Western relief organizations (the American Red Cross, the Central Prisoner of War Committee for British POWs, and the Bureau de Secours Aux Prisonniers de Guerre for French and Belgian prisoners) greatly augmented the rations provided by the Germans with food parcels.

Eastern Allied POWs died at a much higher rate: the Russian rate was 4.61 percent, the Italian 5.46 percent, the Serbian 5.81 percent, and the Romanian rate was an amazing 28.64 percent. Three factors explain this divergence: Western prisoners were generally in better health than their Eastern counterparts; Western POWs also arrived in prison camps clad in warmer and sturdier clothing; and, most importantly, Western prisoners had access to more food than Eastern POWs. Western relief organizations (the American Red Cross, the Central Prisoner of War Committee for British POWs, and the Bureau de Secours Aux Prisonniers de Guerre for French and Belgian prisoners) greatly augmented the rations provided by the Germans with food parcels.  Despite Western advantages, 94 percent of Russian POWs survived the war primarily on German rations, while 97 percent of Western prisoners returned home. The German government clearly intended to care for Allied prisoners as humanely as possible, given the nation's limited resources. Less than 5 percent of the total war prisoner population died under German care, including prisoners grievously wounded in battle. While this was three times greater than the death rate in American military prison camps in France, the number was significantly lower than the 30 percent of Central Power POWs that died in Russian prison camps.28

Despite Western advantages, 94 percent of Russian POWs survived the war primarily on German rations, while 97 percent of Western prisoners returned home. The German government clearly intended to care for Allied prisoners as humanely as possible, given the nation's limited resources. Less than 5 percent of the total war prisoner population died under German care, including prisoners grievously wounded in battle. While this was three times greater than the death rate in American military prison camps in France, the number was significantly lower than the 30 percent of Central Power POWs that died in Russian prison camps.28

29

American officials had to be aware of political controversies during their inspection tours. At a general level, inspectors

had to consider equal treatment among various nationalities. Eric F. Wood, a U.S. attaché assigned to the embassy in

Paris, inspected two German prison camps that contained French and British POWs early in the war. In December 1914, he found

that the prison camp at Zossen, which contained twenty thousand French prisoners at the time, met or exceeded his expectations. One

month later, Wood visited the prison at Döberitz, which held four thousand British and four thousand Russian war prisoners at the time.

Conditions at Döberitz were far inferior to the facilities for the French at Zossen. Many observers concluded that

friction between the Germans and their British captives resulted in abuses. Political disputes extended to groups in various

forms.

American officials had to be aware of political controversies during their inspection tours. At a general level, inspectors

had to consider equal treatment among various nationalities. Eric F. Wood, a U.S. attaché assigned to the embassy in

Paris, inspected two German prison camps that contained French and British POWs early in the war. In December 1914, he found

that the prison camp at Zossen, which contained twenty thousand French prisoners at the time, met or exceeded his expectations. One