Table of Contents

Chapter 16

The Armistice and Restoration of American YMCA WPA Service in Central Europe: Repatriation of Western Allied Prisoners

1

The signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 marked the end of fighting on the Western Front and the resumption

of American YMCA operations in Central Europe. British, American, French, Italian, Belgian, and Portuguese prisoners

were eager to return home, and the Allies established a rapid repatriation schedule under the terms of the Armistice. With the end of the war, Western

POWs chafed under continued captivity as they waited impatiently for transportation.

The signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 marked the end of fighting on the Western Front and the resumption

of American YMCA operations in Central Europe. British, American, French, Italian, Belgian, and Portuguese prisoners

were eager to return home, and the Allies established a rapid repatriation schedule under the terms of the Armistice. With the end of the war, Western

POWs chafed under continued captivity as they waited impatiently for transportation.

Threats of rioting arose at many German prison camps, and commandants turned to Association secretaries to help

restore order. Despite transportation bottlenecks, the Allies removed most of the Western POWs from Germany faster

than scheduled, leaving only Russian prisoners languishing in prison camps. The end of the war also marked

serious dissension within the ranks of the World's Alliance. Animosity between the International Committee and the

German National YMCA came to a head during the last months of the war and threatened the cohesiveness of the World's

Alliance. Not only was World War I a threat to Western civilization, it was also a serious blow to Christian

Internationalism.

Threats of rioting arose at many German prison camps, and commandants turned to Association secretaries to help

restore order. Despite transportation bottlenecks, the Allies removed most of the Western POWs from Germany faster

than scheduled, leaving only Russian prisoners languishing in prison camps. The end of the war also marked

serious dissension within the ranks of the World's Alliance. Animosity between the International Committee and the

German National YMCA came to a head during the last months of the war and threatened the cohesiveness of the World's

Alliance. Not only was World War I a threat to Western civilization, it was also a serious blow to Christian

Internationalism.

Post-War YMCA WPA Operations for American Prisoners

2

When the Armistice was signed, the WPA program was well established at Rastatt. Conrad Hoffman visited the prison

shortly after the cease-fire and found a chaotic situation. The German Soldiers' Council had opened the gates of

the prison after the Armistice, and the American POWs simply took over the city. Hoffman found U.S. prisoners

strolling down the sidewalks and vulnerable to all kinds of trouble. The YMCA secretary persuaded Sergeant Edgar

Halyburton to restore discipline and confine the men to the prison compound for their own safety.

When the Armistice was signed, the WPA program was well established at Rastatt. Conrad Hoffman visited the prison

shortly after the cease-fire and found a chaotic situation. The German Soldiers' Council had opened the gates of

the prison after the Armistice, and the American POWs simply took over the city. Hoffman found U.S. prisoners

strolling down the sidewalks and vulnerable to all kinds of trouble. The YMCA secretary persuaded Sergeant Edgar

Halyburton to restore discipline and confine the men to the prison compound for their own safety.

Under these unique circumstances, the Association would have to provide even more activities to keep the American

prisoners busy until they were shipped home. The YMCA arranged for more concerts and athletic events. Most

importantly, Hoffman prepared for a special Thanksgiving in Germany. The prisoners watched a championship

football game and many participated in an exhibit of handicraft projects. In the evening, the Association

sponsored a vaudeville show. The YMCA also provided each of the POWs with a good, substantial blanket and

a mess outfit.1

Under these unique circumstances, the Association would have to provide even more activities to keep the American

prisoners busy until they were shipped home. The YMCA arranged for more concerts and athletic events. Most

importantly, Hoffman prepared for a special Thanksgiving in Germany. The prisoners watched a championship

football game and many participated in an exhibit of handicraft projects. In the evening, the Association

sponsored a vaudeville show. The YMCA also provided each of the POWs with a good, substantial blanket and

a mess outfit.1

3

Thanksgiving evening was the last time Hoffman would spend with the American POWs in Rastatt. They left

the camp on 5 December 1918 for repatriation to Switzerland. The Germans herded the American POWs into boxcars

for their trip across the border, and they expected to travel in such discomfort all the way to France. The

American POWs, however, received a warm welcome in Geneva. The U.S. Sanitary Corps sent five special trains,

each consisting of sixteen coaches-all sleepers, except for two kitchen cars. These trains could each accommodate

up to six hundred passengers in comfort. Each carried a staff of three doctors, three nurses, and thirty-five enlisted men,

Red Cross members of the U.S. Medical Corps.

Thanksgiving evening was the last time Hoffman would spend with the American POWs in Rastatt. They left

the camp on 5 December 1918 for repatriation to Switzerland. The Germans herded the American POWs into boxcars

for their trip across the border, and they expected to travel in such discomfort all the way to France. The

American POWs, however, received a warm welcome in Geneva. The U.S. Sanitary Corps sent five special trains,

each consisting of sixteen coaches-all sleepers, except for two kitchen cars. These trains could each accommodate

up to six hundred passengers in comfort. Each carried a staff of three doctors, three nurses, and thirty-five enlisted men,

Red Cross members of the U.S. Medical Corps.

In addition, American YMCA secretaries joined the train crews to minister to these men. As the American POWs

disembarked from the German boxcars, they were met by these trains, which had "U.S." painted on the sides and

were decorated with American flags. The former prisoners were impressed with the luxuries the cars offered,

especially the pillows and the sheets on the beds. After the trains passed through the American lines, the

POWs met more Association secretaries who provided food, shelter, and clothing, serving as many as 1,900 men

in a few hours. The ex-prisoners then continued to Vichy to rest before they returned home or were assigned

back to their military commands.2

In addition, American YMCA secretaries joined the train crews to minister to these men. As the American POWs

disembarked from the German boxcars, they were met by these trains, which had "U.S." painted on the sides and

were decorated with American flags. The former prisoners were impressed with the luxuries the cars offered,

especially the pillows and the sheets on the beds. After the trains passed through the American lines, the

POWs met more Association secretaries who provided food, shelter, and clothing, serving as many as 1,900 men

in a few hours. The ex-prisoners then continued to Vichy to rest before they returned home or were assigned

back to their military commands.2

4

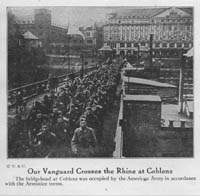

Under the terms of the Armistice, units of the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) were to occupy Coblenz to give the Americans a bridgehead

over the Rhine. The American Association followed the U.S. Army of Occupation into Germany to provide American

troops with the Four-fold Program. The secretaries opened YMCA huts and recreation centers to maintain morale

among the U.S. troops. The American YMCA also sent secretaries to Mannheim in January 1919, an important

railroad junction through which Allied POWs passed. Red Triangle workers met Red Cross trains and provided

the ex-prisoners with chocolate, coffee, cigarettes, hot drinks, and bullion. For POWs too sick to leave

military hospitals, the Association sent supplies to help improve their condition. During a two week period

in early January, at the apex of Allied POW movements, the American YMCA served 10,261 prisoners from France,

Italy, Belgium, Britain, Serbia, Romania, the U.S., and a few civilians in Mannheim.3

Under the terms of the Armistice, units of the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) were to occupy Coblenz to give the Americans a bridgehead

over the Rhine. The American Association followed the U.S. Army of Occupation into Germany to provide American

troops with the Four-fold Program. The secretaries opened YMCA huts and recreation centers to maintain morale

among the U.S. troops. The American YMCA also sent secretaries to Mannheim in January 1919, an important

railroad junction through which Allied POWs passed. Red Triangle workers met Red Cross trains and provided

the ex-prisoners with chocolate, coffee, cigarettes, hot drinks, and bullion. For POWs too sick to leave

military hospitals, the Association sent supplies to help improve their condition. During a two week period

in early January, at the apex of Allied POW movements, the American YMCA served 10,261 prisoners from France,

Italy, Belgium, Britain, Serbia, Romania, the U.S., and a few civilians in Mannheim.3

5

On 26 November 1918, Hoffman visited the American officers held prisoner at Villingen to prepare them for

departure for Switzerland. They left by train at the end of November for repatriation to France.

On 26 November 1918, Hoffman visited the American officers held prisoner at Villingen to prepare them for

departure for Switzerland. They left by train at the end of November for repatriation to France.

With the departure of the American POWs from Rastatt and Villingen, Hoffman estimated that only three hunded U.S.

prisoners remained scattered across Germany. W. W. Husband of the American Red Cross, who was assigned to

Berlin, visited these men and prepared them for their trip out of captivity.4

With the departure of the American POWs from Rastatt and Villingen, Hoffman estimated that only three hunded U.S.

prisoners remained scattered across Germany. W. W. Husband of the American Red Cross, who was assigned to

Berlin, visited these men and prepared them for their trip out of captivity.4

Allied Repatriation to Western Europe

6

For Allied prisoners working in the Etappensgebiet and assigned to the prison camps on the west bank

of the Rhine, the Germans simply opened the prison gates and ordered the POWs to march west.

For Allied prisoners working in the Etappensgebiet and assigned to the prison camps on the west bank

of the Rhine, the Germans simply opened the prison gates and ordered the POWs to march west.

At the border, the Germans gave the prisoners a piece of bread and released them. The American YMCA heard about

the arrival of Allied prisoners and rushed supplies to them. Walter S. Schutz and James E. Perry were in charge of

American YMCA relief plans in anticipation of the arrival of American POWs from Germany, and they arranged for

Red Triangle relief trucks from every Association center on the American front to wait at relief points along

the now quiet battle lines.

At the border, the Germans gave the prisoners a piece of bread and released them. The American YMCA heard about

the arrival of Allied prisoners and rushed supplies to them. Walter S. Schutz and James E. Perry were in charge of

American YMCA relief plans in anticipation of the arrival of American POWs from Germany, and they arranged for

Red Triangle relief trucks from every Association center on the American front to wait at relief points along

the now quiet battle lines.

At Baccarat, Red Triangle workers assisted 1,400 British prisoners with hot chocolate, food, and clothing.

YMCA secretaries also met seven hundred British and Italian POWs at Nancy, and seven hundred British prisoners at Luneville (many

of these men were stragglers who the Germans had not yet transported into the empire for incarceration).5

At Baccarat, Red Triangle workers assisted 1,400 British prisoners with hot chocolate, food, and clothing.

YMCA secretaries also met seven hundred British and Italian POWs at Nancy, and seven hundred British prisoners at Luneville (many

of these men were stragglers who the Germans had not yet transported into the empire for incarceration).5

7

While Germany did not suffer the disorder and psychological collapse that accompanied defeat in Austria, a

few problems hindered the Allied repatriation process. In comparison to Austria-Hungary and Russia, the

transportation of former POWs home was carried out with skill and success in Germany. Problems did emerge,

however, and some prison camps became chaotic for several reasons. Many German officers disappeared with the

Armistice, fearful of the wrath of the growing German revolution, so guards simply threw open the gates.

Thousands of POWs took advantage of the situation and headed for Berlin. Prisoners assigned to

Arbeitskommandos, fearful that they would be left behind during the repatriation process, dropped

their tools and flooded their parent camps.

While Germany did not suffer the disorder and psychological collapse that accompanied defeat in Austria, a

few problems hindered the Allied repatriation process. In comparison to Austria-Hungary and Russia, the

transportation of former POWs home was carried out with skill and success in Germany. Problems did emerge,

however, and some prison camps became chaotic for several reasons. Many German officers disappeared with the

Armistice, fearful of the wrath of the growing German revolution, so guards simply threw open the gates.

Thousands of POWs took advantage of the situation and headed for Berlin. Prisoners assigned to

Arbeitskommandos, fearful that they would be left behind during the repatriation process, dropped

their tools and flooded their parent camps.

Russian prisoners assigned to labor detachments joined this rush, although their chances of repatriation were

slim. They overwhelmed the facilities at most camps, leaving the POWs with no food supplies and little shelter.

The lack of discipline was especially hard on POWs still confined to military hospitals.6

Russian prisoners assigned to labor detachments joined this rush, although their chances of repatriation were

slim. They overwhelmed the facilities at most camps, leaving the POWs with no food supplies and little shelter.

The lack of discipline was especially hard on POWs still confined to military hospitals.6

8

To help relieve these conditions, Hoffman and the neutral WPA field secretaries continued their services

in prison camps across Germany. In the minds of Western Allied POWs, repatriation was an incredibly slow

and difficult process. The German transportation infrastructure was burdened by the millions of soldiers

returning home from the Western Front.

To help relieve these conditions, Hoffman and the neutral WPA field secretaries continued their services

in prison camps across Germany. In the minds of Western Allied POWs, repatriation was an incredibly slow

and difficult process. The German transportation infrastructure was burdened by the millions of soldiers

returning home from the Western Front.

It took time for the Allies to set up an organization to implement the repatriation process, and as prisoners

grew impatient, they became increasingly dangerous. At Lamsdorf, the French POWs sent an ultimatum to the camp

commandant in early December. They had not received any food parcels from the Netherlands or Switzerland, and

threatened to evacuate the camp in force and seize the city unless they were repatriated within five days.

It took time for the Allies to set up an organization to implement the repatriation process, and as prisoners

grew impatient, they became increasingly dangerous. At Lamsdorf, the French POWs sent an ultimatum to the camp

commandant in early December. They had not received any food parcels from the Netherlands or Switzerland, and

threatened to evacuate the camp in force and seize the city unless they were repatriated within five days.

The German commandant and the POWs requested that an Association secretary be sent to calm the prisoners and

restore order. Russian POWs also became a serious threat to security. With no food in the prison camps and no

hope of food parcels from home, they left the compounds and foraged the countryside. They became a menace to

law and order, and fearful German towns demanded troops for protection. In Danzig, thirty thousand Russian POWs seized

four merchant ships scheduled to transport British prisoners to England. The problem was that the Russian

government refused to accept these men. With the permission of the Ministry of War, Hoffman sent WPA field

secretaries to help restore order and assure Western POWs that they would soon return home. The return of

German officers also helped reinstitute some discipline in the camps.7

The German commandant and the POWs requested that an Association secretary be sent to calm the prisoners and

restore order. Russian POWs also became a serious threat to security. With no food in the prison camps and no

hope of food parcels from home, they left the compounds and foraged the countryside. They became a menace to

law and order, and fearful German towns demanded troops for protection. In Danzig, thirty thousand Russian POWs seized

four merchant ships scheduled to transport British prisoners to England. The problem was that the Russian

government refused to accept these men. With the permission of the Ministry of War, Hoffman sent WPA field

secretaries to help restore order and assure Western POWs that they would soon return home. The return of

German officers also helped reinstitute some discipline in the camps.7

9

When the Allied Military Missions arrived in Berlin to set up repatriation operations, the YMCA was in a strong

position to provide assistance. Allied officers called on the WPA Office for accurate information about German prison camps,

their location, and their organization. Three American officers with YMCA experience who had been captured by the

Germans were released by the U.S. Army to conduct Association work.

When the Allied Military Missions arrived in Berlin to set up repatriation operations, the YMCA was in a strong

position to provide assistance. Allied officers called on the WPA Office for accurate information about German prison camps,

their location, and their organization. Three American officers with YMCA experience who had been captured by the

Germans were released by the U.S. Army to conduct Association work.

They visited prison camps to investigate and report on conditions. In Bavaria, American secretaries arranged to

transport British invalid prisoners back to England. The Allied Military Missions needed an effective transportation

system to get Western POWs out of Germany. British and French POWs in northern Germany traveled to Baltic ports

for transportation to Denmark.

They visited prison camps to investigate and report on conditions. In Bavaria, American secretaries arranged to

transport British invalid prisoners back to England. The Allied Military Missions needed an effective transportation

system to get Western POWs out of Germany. British and French POWs in northern Germany traveled to Baltic ports

for transportation to Denmark.

From Danish ports, these men returned home to England and France. British and French prisoners in southern

Germany took trains to Switzerland.

From Danish ports, these men returned home to England and France. British and French prisoners in southern

Germany took trains to Switzerland.

There they transferred to French trains once accommodations became available. Italian prisoners also headed south

to Switzerland, where they caught trains to cross the Alps. To comfort these former POWs, the YMCA provided housing

for men in neutral countries waiting for transportation. The YMCA also provided coats and shoes to Italian POWs as

part of the repatriation process. This became a serious problem in Denmark, because the facilities for transportation

between Denmark and England were inadequate to meet the great demand. As a result, the Allies had to slow down the

repatriation process between Germany and Denmark-leaving men idle in prison camps-to prevent congestion in

Copenhagen.8

There they transferred to French trains once accommodations became available. Italian prisoners also headed south

to Switzerland, where they caught trains to cross the Alps. To comfort these former POWs, the YMCA provided housing

for men in neutral countries waiting for transportation. The YMCA also provided coats and shoes to Italian POWs as

part of the repatriation process. This became a serious problem in Denmark, because the facilities for transportation

between Denmark and England were inadequate to meet the great demand. As a result, the Allies had to slow down the

repatriation process between Germany and Denmark-leaving men idle in prison camps-to prevent congestion in

Copenhagen.8

10

To help ease the POW problem in the German capital, Hoffman opened a new Berlin Association foyer for these men.

The foyer included a lounge, and the YMCA offered the former POWs light refreshments. The British and French

military commissions provided tea, biscuits, and coffee, and Hoffman obtained a piano and phonograph to provide

entertainment.

To help ease the POW problem in the German capital, Hoffman opened a new Berlin Association foyer for these men.

The foyer included a lounge, and the YMCA offered the former POWs light refreshments. The British and French

military commissions provided tea, biscuits, and coffee, and Hoffman obtained a piano and phonograph to provide

entertainment.

Prisoners also received writing paper and free postage, and wrote an average of five hundred letters a day. Hoffman sent

these letters by special packet to Paris, because the mail did not yet travel from Germany through regular

channels. A committee of American women in the capital volunteered to serve as hostesses every day. Hoffman

reported that these ladies did excellent work and helped expand the program. The small foyer served an average

of 1,800 prisoners a day, and the women served two thousand cups of tea daily.

Prisoners also received writing paper and free postage, and wrote an average of five hundred letters a day. Hoffman sent

these letters by special packet to Paris, because the mail did not yet travel from Germany through regular

channels. A committee of American women in the capital volunteered to serve as hostesses every day. Hoffman

reported that these ladies did excellent work and helped expand the program. The small foyer served an average

of 1,800 prisoners a day, and the women served two thousand cups of tea daily.

The foyer was visited by a cosmopolitan clientele, which included former POWs from France, Italy, Romania,

Serbia, Senegal, and Britain. In December 1918, Hoffman organized a special Christmas celebration at a Berlin

military hospital that cared for three hundred wounded and sick Allied prisoners (this number included sixty-five

British and two American POWs).

The foyer was visited by a cosmopolitan clientele, which included former POWs from France, Italy, Romania,

Serbia, Senegal, and Britain. In December 1918, Hoffman organized a special Christmas celebration at a Berlin

military hospital that cared for three hundred wounded and sick Allied prisoners (this number included sixty-five

British and two American POWs).

American and British generals assigned to their country's military commissions attended the event. While Hoffman

planned to rent a larger facility to meet the demand, he realized that most of the prisoners would soon be gone.

The repatriation process had begun in November 1918, and all of the British, French, Italian, and American POWs

had departed Germany by February 1919. Even by December 25, all of the Western Allied POWs had boarded transports

for home except for those housed in two prison camps, and they soon followed. The few remaining Allied POWs were

sick and wounded hospital patients who could not be immediately transported.9

American and British generals assigned to their country's military commissions attended the event. While Hoffman

planned to rent a larger facility to meet the demand, he realized that most of the prisoners would soon be gone.

The repatriation process had begun in November 1918, and all of the British, French, Italian, and American POWs

had departed Germany by February 1919. Even by December 25, all of the Western Allied POWs had boarded transports

for home except for those housed in two prison camps, and they soon followed. The few remaining Allied POWs were

sick and wounded hospital patients who could not be immediately transported.9

American Social Welfare Programs in Post-War Germany

11 With the reemergence of the American YMCA in Germany after the Armistice, Hoffman sought to establish social welfare programs for the German people. The rapid demobilization of eight million German soldiers had a tremendous economic impact. Factories stood idle due to the lack of raw materials and the political uncertainty of the peace negotiations underway in Versailles. More importantly, the Allies maintained the naval blockade to guarantee that the Germans would sign the peace treaty. The lack of food in Germany threatened to kill large numbers of the young and elderly. The German National YMCA Committee offered Hoffman the chairmanship of a department of social service. The focus of this organization was to develop athletics and play among German boys, as well as welfare work programs in industrial and country districts.10

12

Another target group for YMCA ministrations was the Polish and Russian laborers stranded in Germany. During the

war, the German government sent agents to occupied Poland to recruit Polish and Russian civilians to work in

various industries in Germany. Accepting promises of high pay and light work, these men ended up conducting

heavy labor in railroad construction, munitions, and factory work. With the Armistice and the demobilization

of the German Army, the government prohibited the employment of enemy aliens to free up jobs for former

soldiers. This edict directly affected the Polish and Russian workers, and they found themselves stranded in

a hostile country. They could no longer earn a living, but also could not return home, because most traffic

between Germany and Poland had ceased. The German government agreed to send Polish workers back to Poland if

they paid the railroad fare, but most men had lost their savings while trying to buy food. When the Poles lost

their jobs, they could not pay their rent, and without rooms, they lost access to food ration cards. To help

these unfortunates, Hoffman received permission from the German government to hire Polish workers as packers,

general errand boys, and custodial workers. While the assistance of the American YMCA provided Polish workers

was meager in relation to the large numbers of stranded refugees, the Association was able to help some Poles

earn enough money to survive and eventually get home.11

Another target group for YMCA ministrations was the Polish and Russian laborers stranded in Germany. During the

war, the German government sent agents to occupied Poland to recruit Polish and Russian civilians to work in

various industries in Germany. Accepting promises of high pay and light work, these men ended up conducting

heavy labor in railroad construction, munitions, and factory work. With the Armistice and the demobilization

of the German Army, the government prohibited the employment of enemy aliens to free up jobs for former

soldiers. This edict directly affected the Polish and Russian workers, and they found themselves stranded in

a hostile country. They could no longer earn a living, but also could not return home, because most traffic

between Germany and Poland had ceased. The German government agreed to send Polish workers back to Poland if

they paid the railroad fare, but most men had lost their savings while trying to buy food. When the Poles lost

their jobs, they could not pay their rent, and without rooms, they lost access to food ration cards. To help

these unfortunates, Hoffman received permission from the German government to hire Polish workers as packers,

general errand boys, and custodial workers. While the assistance of the American YMCA provided Polish workers

was meager in relation to the large numbers of stranded refugees, the Association was able to help some Poles

earn enough money to survive and eventually get home.11

Nationalist Problems within the World's Alliance of YMCAs

13

A crisis developed in the Association movement as a direct result of conflicting national policies. At the turn

of the century, the paramount ideology of the organization was Christian Internationalism, and all of the members

of the World's Alliance were dedicated to the goal of evangelizing the world. When the war began in July 1914, the

Association movement was led by three major national YMCA organizations: the English National YMCA Council, the

German National YMCA Committee, and the International Committee of the YMCAs of North America. The World's Alliance

immediately acknowledged the terrible crisis the war represented, not only in terms of civilized Christian nations

participating in fratricide, but also the possibility of the collapse of the international Association movement.

The British and German YMCAs were now mortal enemies, and it was unlikely that they could work together to promote

global social welfare work. The French, Italian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Associations were minor movements

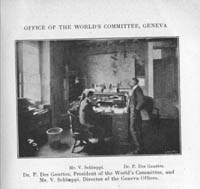

and could not contribute much to their national war efforts or the international YMCA movement. Paul Des Gouttes,

President of the World's Alliance, stressed the importance of the organization's political neutrality, and that

members should follow only the banner of Jesus Christ. Des Gouttes recognized that national YMCA committees of

belligerent nations had a patriotic duty to serve the young men of their countries who had been recently called

to war. The YMCAs representing neutral states, however, had to do everything in their power to help alleviate the

suffering the war had created. As a result, the bulk of this burden, especially funding and manpower, fell on the

shoulders of the American YMCA.12

A crisis developed in the Association movement as a direct result of conflicting national policies. At the turn

of the century, the paramount ideology of the organization was Christian Internationalism, and all of the members

of the World's Alliance were dedicated to the goal of evangelizing the world. When the war began in July 1914, the

Association movement was led by three major national YMCA organizations: the English National YMCA Council, the

German National YMCA Committee, and the International Committee of the YMCAs of North America. The World's Alliance

immediately acknowledged the terrible crisis the war represented, not only in terms of civilized Christian nations

participating in fratricide, but also the possibility of the collapse of the international Association movement.

The British and German YMCAs were now mortal enemies, and it was unlikely that they could work together to promote

global social welfare work. The French, Italian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Associations were minor movements

and could not contribute much to their national war efforts or the international YMCA movement. Paul Des Gouttes,

President of the World's Alliance, stressed the importance of the organization's political neutrality, and that

members should follow only the banner of Jesus Christ. Des Gouttes recognized that national YMCA committees of

belligerent nations had a patriotic duty to serve the young men of their countries who had been recently called

to war. The YMCAs representing neutral states, however, had to do everything in their power to help alleviate the

suffering the war had created. As a result, the bulk of this burden, especially funding and manpower, fell on the

shoulders of the American YMCA.12

14

As the war progressed, a degree of tension began to emerge, both between the American YMCA and the World's Alliance

and between the World's Alliance and the German National YMCA. Problems with the German YMCA developed first. As

Archibald Harte sought to gain access to German prison camps, he increasingly came in contact with German Kultur,

which he perceived as a subtle form of propaganda. The German YMCA incorporated this propaganda into its work, and

encouraged German secretaries working in prison camps to disseminate the knowledge.13

As the war progressed, a degree of tension began to emerge, both between the American YMCA and the World's Alliance

and between the World's Alliance and the German National YMCA. Problems with the German YMCA developed first. As

Archibald Harte sought to gain access to German prison camps, he increasingly came in contact with German Kultur,

which he perceived as a subtle form of propaganda. The German YMCA incorporated this propaganda into its work, and

encouraged German secretaries working in prison camps to disseminate the knowledge.13

15

At the dedication of the Association hall at Göttingen in March 1915, Professor Carl Stange delivered an

unusual address, stating that this facility could now be enjoyed by the Allied POWs to improve themselves by

absorbing Kultur. Prisoners would learn about the superiority of German civilization and gain an appreciation of

higher thinking. Once they became ingrained with Kultur, they could return home after the war as the

"fellow subjects [of the German empire] of tomorrow." Stange declared:

At the dedication of the Association hall at Göttingen in March 1915, Professor Carl Stange delivered an

unusual address, stating that this facility could now be enjoyed by the Allied POWs to improve themselves by

absorbing Kultur. Prisoners would learn about the superiority of German civilization and gain an appreciation of

higher thinking. Once they became ingrained with Kultur, they could return home after the war as the

"fellow subjects [of the German empire] of tomorrow." Stange declared:

If it is for us beyond all doubt that German culture, not only with respect to economic and industrial life, but also with respect to the wealth of intellectual life and to the depth and strength of ethical considerations, is far in advance of neighboring nations, it is the more important for future times of peace that we should seek to give as deep an impression of this superiority as possible to those of the prisoners who may in intellectual respects deserve consideration. It is the more important for us, since judging from the present results of the war, we may suppose that in some of the prisoners of today we have before us the fellow subjects of tomorrow.14

The Germans planned to use Association and other educational programs to prepare the way for a post-war Pax Germanica. American secretaries exposed to this propaganda were dismayed by the lack of an "international sense" among German Red Triangle workers and their failure to comprehend the nationalist feelings of these prisoners. Instead, the Germans were self-absorbed and confident of their Teutonic superiority.15

16 To a large extent, American secretaries attributed problems with the German YMCA to the state church in Germany. As Americans imbued with the First Amendment, Harte and Hoffman were suspicious of the influence of the German state church. Hoffman described the German church as "the mouthpiece of the state rather than God…" Democracy would not emerge from the bottom up through the church under Kaisertum; rather, national policy was preached from the country's pulpits. Hoffman particularly lamented this fact because one of the few positive developments of the war was a national religious awakening-many Germans had sought spiritual guidance during their period of intense suffering. From Hoffman's perspective, the German church was incapable of taking advantage of this revivalism, because the state church had nothing vital or spiritual to offer men seeking renewal. Hoffman characterized the German church as an Old Testament institution, which focused on law and retribution. The church had too much control over education, and was too deeply invested in the protection of the status quo. At the same time, it failed to take a leading role in social movements. The close ties between the German National YMCA and the state church left the former organization equally moribund.16

Crisis within the World's Alliance

17

The German National YMCA Committee believed that the World's Alliance was biased in favor of the Allies almost

from the very beginning of the war. On 19 August 1914, the German National Secretary reproached the World's

Committee for failing to be neutral or impartial, and these feelings would only grow as the war progressed.

A number of possible factors contributed to this German perception. Although the majority of the members of

the World's Committee were Swiss citizens, Emmanuel Sautter (one of the two General Secretaries) was French,

and W. H. Underwood was English. One of Sautter's first acts was to leave his post to establish relief services

for French troops fighting the German invasion. In addition, the YMCA had British origins, since Sir George

Williams had founded it in London in 1844. The British YMCA had strong ties with the World's Alliance, but

remained an independent organization.

The German National YMCA Committee believed that the World's Alliance was biased in favor of the Allies almost

from the very beginning of the war. On 19 August 1914, the German National Secretary reproached the World's

Committee for failing to be neutral or impartial, and these feelings would only grow as the war progressed.

A number of possible factors contributed to this German perception. Although the majority of the members of

the World's Committee were Swiss citizens, Emmanuel Sautter (one of the two General Secretaries) was French,

and W. H. Underwood was English. One of Sautter's first acts was to leave his post to establish relief services

for French troops fighting the German invasion. In addition, the YMCA had British origins, since Sir George

Williams had founded it in London in 1844. The British YMCA had strong ties with the World's Alliance, but

remained an independent organization.

18

Relations between the American YMCA and the German Association were cordial during the early part of the war.

Harte developed strong ties with Gerhard Niedermeyer, and the Americans performed a real service for German

POWs in Russian prisons. Although ties between the two nations deteriorated due to Germany's unconditional

submarine warfare, as well as American munitions sales, war loans to the Allies, and other violations of

international neutrality laws, the German public recognized that the American YMCA's service to POWs met a

real humanitarian need. But once the Wilson Administration broke off diplomatic relations with the German

government in February 1917, this good will was lost. John R. Mott's participation with the Root Mission to

bolster the Provisional Government in Russia infuriated the German National YMCA Council. G. Rosenkranz, a member of the German National

Committee, denounced the World's Alliance for failing to restrain Mott's political activities in August 1917.

This led to a crisis within the international organization. Rosenkranz threatened that the German YMCA would

leave the World's Alliance unless the World's Committee condemned Mott's actions. Des Gouttes responded to

Rosenkranz's threat on 25 September 1917, declaring that the American General Secretary had acted on his own

accord, and that his activities were beyond the purview of the World's Alliance.17

Relations between the American YMCA and the German Association were cordial during the early part of the war.

Harte developed strong ties with Gerhard Niedermeyer, and the Americans performed a real service for German

POWs in Russian prisons. Although ties between the two nations deteriorated due to Germany's unconditional

submarine warfare, as well as American munitions sales, war loans to the Allies, and other violations of

international neutrality laws, the German public recognized that the American YMCA's service to POWs met a

real humanitarian need. But once the Wilson Administration broke off diplomatic relations with the German

government in February 1917, this good will was lost. John R. Mott's participation with the Root Mission to

bolster the Provisional Government in Russia infuriated the German National YMCA Council. G. Rosenkranz, a member of the German National

Committee, denounced the World's Alliance for failing to restrain Mott's political activities in August 1917.

This led to a crisis within the international organization. Rosenkranz threatened that the German YMCA would

leave the World's Alliance unless the World's Committee condemned Mott's actions. Des Gouttes responded to

Rosenkranz's threat on 25 September 1917, declaring that the American General Secretary had acted on his own

accord, and that his activities were beyond the purview of the World's Alliance.17

19

This controversy was far from over. In April 1918, Mott sailed across the Atlantic to inspect American YMCA

operations on the Western Front. While traveling between France and Italy, he stopped first in Bern, Switzerland,

where he held meetings with Christian Phildius and Archibald Harte regarding World's Alliance WPA operations,

which were supported by American YMCA funds. In company with Harte and Phildius, Mott continued to Geneva, where

they attended a meeting of the Executive Committee. This meeting was extremely stormy, an event not described in

detail in Mott's biography. Serious trouble had been brewing between the World's Committee, the German National

Committee, and Harte. The Germans had again threatened to break relations with the World's Alliance, and Des

Gouttes called an emergency session of the Executive Committee to address this issue on April 28. Participants

at the meeting included Mott, Harte, Hoffman, Thomas C. Hall, Des Gouttes, Phildius, Dr. F. Louis Perrot, Auguste

Rappard, Professor Eugene Choicy, Pastor James E. Siordet, and a number of World's Alliance secretaries including

Victor Schlaeppi, Theodore Geisendorf, Rudolf Horner, Julius Hecker, Ernst Sartorius, and W. H. Underwood. Many

members of the World's Alliance had problems with Harte's approach to diplomacy. Phildius believed that Harte

actively undermined the authority of the World's Committee by working through national YMCA committees and

bypassing World's Alliance authorities. Phildius cited Harte's courting of Niedermeyer of the German YMCA

and the Russian Miyak to gain access to war prisoners. To a degree, this resentment reflected Phildius'

failure to negotiate early agreements with Berlin and Vienna, in contrast to Harte's success with the German

and Austro-Hungarian governments. When Phildius later gained access to Allied POWs in Bulgaria and Turkey,

Harte threatened to undermine these agreements by denying American funds for the projects. Des Gouttes shared

Phildius' concerns about Harte. In May 1916, the World's Alliance president complained to Count Konstantin

Pahlen, patron of the Miyak, that Harte had taken on airs regarding his diplomatic relations with the

German, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian emperors. The World's Committee wanted Mott to reel Harte in and keep

the International General Secretary under control.18

This controversy was far from over. In April 1918, Mott sailed across the Atlantic to inspect American YMCA

operations on the Western Front. While traveling between France and Italy, he stopped first in Bern, Switzerland,

where he held meetings with Christian Phildius and Archibald Harte regarding World's Alliance WPA operations,

which were supported by American YMCA funds. In company with Harte and Phildius, Mott continued to Geneva, where

they attended a meeting of the Executive Committee. This meeting was extremely stormy, an event not described in

detail in Mott's biography. Serious trouble had been brewing between the World's Committee, the German National

Committee, and Harte. The Germans had again threatened to break relations with the World's Alliance, and Des

Gouttes called an emergency session of the Executive Committee to address this issue on April 28. Participants

at the meeting included Mott, Harte, Hoffman, Thomas C. Hall, Des Gouttes, Phildius, Dr. F. Louis Perrot, Auguste

Rappard, Professor Eugene Choicy, Pastor James E. Siordet, and a number of World's Alliance secretaries including

Victor Schlaeppi, Theodore Geisendorf, Rudolf Horner, Julius Hecker, Ernst Sartorius, and W. H. Underwood. Many

members of the World's Alliance had problems with Harte's approach to diplomacy. Phildius believed that Harte

actively undermined the authority of the World's Committee by working through national YMCA committees and

bypassing World's Alliance authorities. Phildius cited Harte's courting of Niedermeyer of the German YMCA

and the Russian Miyak to gain access to war prisoners. To a degree, this resentment reflected Phildius'

failure to negotiate early agreements with Berlin and Vienna, in contrast to Harte's success with the German

and Austro-Hungarian governments. When Phildius later gained access to Allied POWs in Bulgaria and Turkey,

Harte threatened to undermine these agreements by denying American funds for the projects. Des Gouttes shared

Phildius' concerns about Harte. In May 1916, the World's Alliance president complained to Count Konstantin

Pahlen, patron of the Miyak, that Harte had taken on airs regarding his diplomatic relations with the

German, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian emperors. The World's Committee wanted Mott to reel Harte in and keep

the International General Secretary under control.18

20

Mott was not prepared to sacrifice his right-hand man in Central and Eastern Europe. He opened his presentation

with an overview of the excellent work the YMCA had accomplished in all countries during the war, and recommended

that the World's Committee take a "wait and see" attitude regarding the German government's threat to recall

neutral secretaries. Mott admitted that it was very difficult to be neutral, especially when one's country was

at war. But he proposed that the American YMCA continue to support POW work on the basis of reciprocity, and

that the International Committee maintain financial support of WPA work (by 31 October 1918, the American YMCA

had extended a total of $100,600 for Allied POW relief work in Germany, approximately 25 percent of the total

WPA budget provided by the International Committee). Regarding funding for WPA operations in Bulgaria and Turkey,

the United States was not at war with these countries, and the funding of World's Alliance WPA operations might

have serious political implications for the American government and the Association's fund-raising campaign. Mott was prepared to provide some financial support, especially for

work in Bulgaria. In addition, he recommended that Harte visit Geneva in the future and consult with the World's

Committee regarding POW relief activities. To avoid potential friction with the World's Committee, Mott planned

to assign Harte to Bern-not as an official member of the International Committee or the World's Committee, but

as a private U.S. citizen. There Harte would set up WPA operations as an independent organization.19

Mott was not prepared to sacrifice his right-hand man in Central and Eastern Europe. He opened his presentation

with an overview of the excellent work the YMCA had accomplished in all countries during the war, and recommended

that the World's Committee take a "wait and see" attitude regarding the German government's threat to recall

neutral secretaries. Mott admitted that it was very difficult to be neutral, especially when one's country was

at war. But he proposed that the American YMCA continue to support POW work on the basis of reciprocity, and

that the International Committee maintain financial support of WPA work (by 31 October 1918, the American YMCA

had extended a total of $100,600 for Allied POW relief work in Germany, approximately 25 percent of the total

WPA budget provided by the International Committee). Regarding funding for WPA operations in Bulgaria and Turkey,

the United States was not at war with these countries, and the funding of World's Alliance WPA operations might

have serious political implications for the American government and the Association's fund-raising campaign. Mott was prepared to provide some financial support, especially for

work in Bulgaria. In addition, he recommended that Harte visit Geneva in the future and consult with the World's

Committee regarding POW relief activities. To avoid potential friction with the World's Committee, Mott planned

to assign Harte to Bern-not as an official member of the International Committee or the World's Committee, but

as a private U.S. citizen. There Harte would set up WPA operations as an independent organization.19

21

Mott's actions did little to settle the controversy between Harte and the World's Committee. While Mott had

instructed Harte to report to the World's Committee on his activities, he also set up the International General

Secretary as an independent entity, supervising WPA operations in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Harte

worked with relative impunity from his offices in Bern and Copenhagen, answerable only to the International

Committee in New York. Mott realized that the Germans needed the YMCA and its WPA relief operations more than

they needed a divorce from the World's Alliance. The American YMCA, with its resources in men and funds, could

act unilaterally. Mott did try to behave as diplomatically as possible regarding the feelings of the World's

Committee members, but it was not enough.20

Mott's actions did little to settle the controversy between Harte and the World's Committee. While Mott had

instructed Harte to report to the World's Committee on his activities, he also set up the International General

Secretary as an independent entity, supervising WPA operations in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Harte

worked with relative impunity from his offices in Bern and Copenhagen, answerable only to the International

Committee in New York. Mott realized that the Germans needed the YMCA and its WPA relief operations more than

they needed a divorce from the World's Alliance. The American YMCA, with its resources in men and funds, could

act unilaterally. Mott did try to behave as diplomatically as possible regarding the feelings of the World's

Committee members, but it was not enough.20

22

The controversy between Harte and the World's Committee rekindled within a few months. In August 1918, a

disagreement arose regarding budget accounts for WPA operations in Austria-Hungary and Turkey. The World's

Alliance took the position that because the United States was no longer neutral, the American YMCA would have

to take a back seat in policy-making regarding POW relief work. According to this plan, the World's Committee

would control WPA operations in the Central Powers to ensure neutrality and continued access to these prison

camps.

The controversy between Harte and the World's Committee rekindled within a few months. In August 1918, a

disagreement arose regarding budget accounts for WPA operations in Austria-Hungary and Turkey. The World's

Alliance took the position that because the United States was no longer neutral, the American YMCA would have

to take a back seat in policy-making regarding POW relief work. According to this plan, the World's Committee

would control WPA operations in the Central Powers to ensure neutrality and continued access to these prison

camps.

From the Geneva organization's perspective, the World's Committee would determine budget allocations and assign

neutral secretaries, while the International Committee would continue to provide the funding. Harte dug in his

heels over this issue. He wrote a frank report to Rappard on 19 August 1918 and disputed the World's Committee's

accusations that Edgar MacNaughten, the American Senior Secretary in Austria-Hungary until the U.S. and the Dual

Monarchy broke off diplomatic relations, had been improperly paid. More importantly, Harte declared that he

considered the WPA to be under the jurisdiction of the International Committee, especially since New York funded

the operations. Harte disapproved of the World's Committee's budgets for Austria-Hungary and Turkey, and he planned

to negotiate personally with the Austro-Hungarian government in Vienna to formulate plans for future operations.

Members of the World's Committee continued to challenge Harte's accounts. Harte, meanwhile, pursued his negotiations

with Austrian officials, and informed the World's Alliance representatives that he would turn over control of WPA

operations in the Dual Monarchy only if they could find a mutual basis for transfer and continuance.21

From the Geneva organization's perspective, the World's Committee would determine budget allocations and assign

neutral secretaries, while the International Committee would continue to provide the funding. Harte dug in his

heels over this issue. He wrote a frank report to Rappard on 19 August 1918 and disputed the World's Committee's

accusations that Edgar MacNaughten, the American Senior Secretary in Austria-Hungary until the U.S. and the Dual

Monarchy broke off diplomatic relations, had been improperly paid. More importantly, Harte declared that he

considered the WPA to be under the jurisdiction of the International Committee, especially since New York funded

the operations. Harte disapproved of the World's Committee's budgets for Austria-Hungary and Turkey, and he planned

to negotiate personally with the Austro-Hungarian government in Vienna to formulate plans for future operations.

Members of the World's Committee continued to challenge Harte's accounts. Harte, meanwhile, pursued his negotiations

with Austrian officials, and informed the World's Alliance representatives that he would turn over control of WPA

operations in the Dual Monarchy only if they could find a mutual basis for transfer and continuance.21

23

Des Gouttes was exasperated and wrote to Mott on 30 August 1918. The World's Alliance President was very upset with Harte, arguing that the

American secretary was working for his own ends and not for the benefit of the Association. He again stressed

that the YMCA had to remain neutral, or Germany and Austria-Hungary would break off relations with the organization.

Des Gouttes accused Harte of seeking to make the World's Committee "a wheel, subordinate to his control." Des Gouttes

essentially offered an ultimatum: either Association work would continue under the direction of neutral YMCA

committees, or there would no longer be any Association work among the war prisoners. This correspondence placed Mott

in a serious dilemma. If he supported Harte and his "pretentious behavior," it would undermine relations with

the World's Alliance and end WPA work in Germany and Austria-Hungary. On the other hand, Harte represented the

International Committee in European WPA work, and to weaken his position as International General Secretary would

place the World's Committee in control of POW relief operations. Des Gouttes asked for more money to continue

Association work in countries where the World's Committee believed it was necessary. Without a level of reciprocity

in financial support, the World's Alliance president feared dangerous reprisals by the Central Powers.22

Des Gouttes was exasperated and wrote to Mott on 30 August 1918. The World's Alliance President was very upset with Harte, arguing that the

American secretary was working for his own ends and not for the benefit of the Association. He again stressed

that the YMCA had to remain neutral, or Germany and Austria-Hungary would break off relations with the organization.

Des Gouttes accused Harte of seeking to make the World's Committee "a wheel, subordinate to his control." Des Gouttes

essentially offered an ultimatum: either Association work would continue under the direction of neutral YMCA

committees, or there would no longer be any Association work among the war prisoners. This correspondence placed Mott

in a serious dilemma. If he supported Harte and his "pretentious behavior," it would undermine relations with

the World's Alliance and end WPA work in Germany and Austria-Hungary. On the other hand, Harte represented the

International Committee in European WPA work, and to weaken his position as International General Secretary would

place the World's Committee in control of POW relief operations. Des Gouttes asked for more money to continue

Association work in countries where the World's Committee believed it was necessary. Without a level of reciprocity

in financial support, the World's Alliance president feared dangerous reprisals by the Central Powers.22

24

Mott chose not to intervene directly, but delayed a decision while providing more funds through the World's Committee.

Phildius and Rappard continued to question Harte's accounts for Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria from late September to

late November 1918. At this point, Germany had signed the Armistice, and the repatriation process had begun for

Western Allied POWs. Harte was extremely upset with criticism of the POW reports he produced during the war. Writing

from Paris in November 1919, he described the serious constraints he worked under for five years as International

General Secretary for WPA Work in Central and Eastern Europe. When he began writing reports early in 1915, he

encouraged the family and friends of POWs in Britain and Canada by focusing on good news coming from German prison

camps. More importantly, he was prohibited from writing about the problems, especially since he wished to gain the

confidence of German officials so that the American YMCA could expand its aid to Allied war prisoners. Shortly

after writing these preliminary reports, he concluded that he had made a serious mistake, and limited his further

reports to detailing conditions in Russia. He wrote these optimistic reports because of the horrible things the

Germans were saying about conditions in Russia, and because he did not find a single prison camp in Russia that

was as bad as the last camp he had visited in Germany (Cassel). In May 1915, Central Power POWs held in Russia

enjoyed considerable freedom and an abundance of food. As the war dragged on, the Russians participated in reprisals,

and conditions in the Tsarist Empire became frightful. Until the Armistice, Harte realized that he had to:

Mott chose not to intervene directly, but delayed a decision while providing more funds through the World's Committee.

Phildius and Rappard continued to question Harte's accounts for Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria from late September to

late November 1918. At this point, Germany had signed the Armistice, and the repatriation process had begun for

Western Allied POWs. Harte was extremely upset with criticism of the POW reports he produced during the war. Writing

from Paris in November 1919, he described the serious constraints he worked under for five years as International

General Secretary for WPA Work in Central and Eastern Europe. When he began writing reports early in 1915, he

encouraged the family and friends of POWs in Britain and Canada by focusing on good news coming from German prison

camps. More importantly, he was prohibited from writing about the problems, especially since he wished to gain the

confidence of German officials so that the American YMCA could expand its aid to Allied war prisoners. Shortly

after writing these preliminary reports, he concluded that he had made a serious mistake, and limited his further

reports to detailing conditions in Russia. He wrote these optimistic reports because of the horrible things the

Germans were saying about conditions in Russia, and because he did not find a single prison camp in Russia that

was as bad as the last camp he had visited in Germany (Cassel). In May 1915, Central Power POWs held in Russia

enjoyed considerable freedom and an abundance of food. As the war dragged on, the Russians participated in reprisals,

and conditions in the Tsarist Empire became frightful. Until the Armistice, Harte realized that he had to:

…pocket the medicine given me by the Germans, or give up the work, and as I thought anything was better than give up the work, I took the medicine and kept quiet. Now, however, that there is no longer the pressure upon me I feel that I never want to go near Germany again. I hope one of these days to write a report of our work, but for the present it is unwise, for I find it impossible to overcome a bitterness against the leaders of the German Student Movement, the German Y.M.C.A., and our World's Committee, who in many ways made our work difficult.23

25

Harte was clearly frustrated with WPA work, but was grateful to have served war prisoners and was thankful to

all the Americans who made this work possible. Mott and Sir Arthur Yapp, Secretary General of the English National

YMCA, agreed that Harte should immediately travel to Jerusalem to establish an Anglo-Saxon YMCA in Palestine. Harte

enthusiastically accepted the task, which represented the fulfillment of a life-long dream. He went to the Holy Land

and did everything possible for the people and the land to bring the Palestinians prosperity and make the mandate a

"land of milk and honey." The Jerusalem Association would also serve as a center for YMCA workers from around the

world, a place to meditate to make Christ pre-eminent in their lives, to promote spiritual growth, and to support

initiatives for worldwide work.24

Harte was clearly frustrated with WPA work, but was grateful to have served war prisoners and was thankful to

all the Americans who made this work possible. Mott and Sir Arthur Yapp, Secretary General of the English National

YMCA, agreed that Harte should immediately travel to Jerusalem to establish an Anglo-Saxon YMCA in Palestine. Harte

enthusiastically accepted the task, which represented the fulfillment of a life-long dream. He went to the Holy Land

and did everything possible for the people and the land to bring the Palestinians prosperity and make the mandate a

"land of milk and honey." The Jerusalem Association would also serve as a center for YMCA workers from around the

world, a place to meditate to make Christ pre-eminent in their lives, to promote spiritual growth, and to support

initiatives for worldwide work.24

26

As has been mentioned, the American YMCA established tenuous relations with the German Association after the

Armistice. Hoffman earnestly sought to help the victims of the war, and he particularly wanted to send YMCA

assistance to German POWs who would be retained in northern France and Belgium to help rebuild the devastated

countryside. German officials offered free labor to the French and Belgian governments to undertake the

reconstruction work as substitutes for German war prisoners. These POWs had suffered a great deal, both

physically and emotionally; many had already spent years in captivity, and the thought of continued imprisonment

after the return of peace was almost unendurable for them. Hoffman also wanted to provide food credits for

German mothers and children through the American Reconstruction Administration (ARA). Under the terms of the

Armistice, the Allied blockade would remain in effect until the Germans signed the final peace treaty. As a

result, the starvation conditions that imperiled the weakest members of German society required immediate

attention. Hoffman sought to obtain food from the ARA through neutral Sweden. He

also reported about the revolutionary conditions that emerged during the early days of the German Republic,

having witnessed the street fighting between the Republicans and the Spartacists in Berlin. Most importantly,

Hoffman wanted to help rebuild the German YMCA. He thought that Niedermeyer would emerge as the new leader of

the organization in the post-war period. He recommended that the International Committee send ten to twenty

American secretaries as a study commission to determine how the American Association could best assist the

post-war German YMCA.25

As has been mentioned, the American YMCA established tenuous relations with the German Association after the

Armistice. Hoffman earnestly sought to help the victims of the war, and he particularly wanted to send YMCA

assistance to German POWs who would be retained in northern France and Belgium to help rebuild the devastated

countryside. German officials offered free labor to the French and Belgian governments to undertake the

reconstruction work as substitutes for German war prisoners. These POWs had suffered a great deal, both

physically and emotionally; many had already spent years in captivity, and the thought of continued imprisonment

after the return of peace was almost unendurable for them. Hoffman also wanted to provide food credits for

German mothers and children through the American Reconstruction Administration (ARA). Under the terms of the

Armistice, the Allied blockade would remain in effect until the Germans signed the final peace treaty. As a

result, the starvation conditions that imperiled the weakest members of German society required immediate

attention. Hoffman sought to obtain food from the ARA through neutral Sweden. He

also reported about the revolutionary conditions that emerged during the early days of the German Republic,

having witnessed the street fighting between the Republicans and the Spartacists in Berlin. Most importantly,

Hoffman wanted to help rebuild the German YMCA. He thought that Niedermeyer would emerge as the new leader of

the organization in the post-war period. He recommended that the International Committee send ten to twenty

American secretaries as a study commission to determine how the American Association could best assist the

post-war German YMCA.25

27

While Hoffman sought to improve relations with the German National YMCA, the International Committee was not

as eager to resume ties. Mott returned to Europe in March 1919, arriving at Southampton, England on March 21.

He promptly caught the flu, which incapacitated him for a week (this occurred during the global influenza

epidemic, which killed millions). While recovering in the hospital, Mott met with Harte and other Association

leaders working on various European projects. Mott then traveled to Paris, where he lobbied on the behalf of

missionaries at the Versailles Peace Conference. President Woodrow Wilson was "so fearfully pushed" that he

could not meet his friend, but Mott did have a "splendid talk" with Colonel Edward House, the president's

personal advisor. Mott then proceeded to Italy for a five day vacation. On his return in April 1919, Mott

traveled through Switzerland, visiting Bern, Lausanne, and Geneva, where he had another stormy session with

the World's Committee. The American and British YMCAs had achieved a great deal of influence and power during

the war, and the World's Committee felt threatened by these developments.

While Hoffman sought to improve relations with the German National YMCA, the International Committee was not

as eager to resume ties. Mott returned to Europe in March 1919, arriving at Southampton, England on March 21.

He promptly caught the flu, which incapacitated him for a week (this occurred during the global influenza

epidemic, which killed millions). While recovering in the hospital, Mott met with Harte and other Association

leaders working on various European projects. Mott then traveled to Paris, where he lobbied on the behalf of

missionaries at the Versailles Peace Conference. President Woodrow Wilson was "so fearfully pushed" that he

could not meet his friend, but Mott did have a "splendid talk" with Colonel Edward House, the president's

personal advisor. Mott then proceeded to Italy for a five day vacation. On his return in April 1919, Mott

traveled through Switzerland, visiting Bern, Lausanne, and Geneva, where he had another stormy session with

the World's Committee. The American and British YMCAs had achieved a great deal of influence and power during

the war, and the World's Committee felt threatened by these developments.

28

Members of the World's Committee proposed that the organization be split into separate European and Anglo-American

organizations, a proposal that would have required abrogating the World's Committee's constitution. With the

support of Harte, Darius A. Davis, and Karl Fries, Mott defused this proposal. He argued that the war had been

fought so that smaller nations and backward peoples might all enjoy equal opportunity. The theory that large

nations dominated the organization did not take into consideration the activity and influence of organizations

like the Norwegian and Swedish Associations. More importantly, the war had been fought to protest against the

idea that a treaty is merely a scrap of paper.

Members of the World's Committee proposed that the organization be split into separate European and Anglo-American

organizations, a proposal that would have required abrogating the World's Committee's constitution. With the

support of Harte, Darius A. Davis, and Karl Fries, Mott defused this proposal. He argued that the war had been

fought so that smaller nations and backward peoples might all enjoy equal opportunity. The theory that large

nations dominated the organization did not take into consideration the activity and influence of organizations

like the Norwegian and Swedish Associations. More importantly, the war had been fought to protest against the

idea that a treaty is merely a scrap of paper.

The constitution of the World's Committee had been built up after years of hard labor, with various World's Conferences

working to revise and improve it. Were they prepared to put the constitution aside without first consulting other

Associations around the world? The proposal was rejected, and this meeting represented a major reconciliation

between the World's Committee and the International Committee. Phildius recognized the importance of this

achievement and thanked Mott for his visit. Mott left Geneva having established better relations among the members

of the World's Committee.26

The constitution of the World's Committee had been built up after years of hard labor, with various World's Conferences

working to revise and improve it. Were they prepared to put the constitution aside without first consulting other

Associations around the world? The proposal was rejected, and this meeting represented a major reconciliation

between the World's Committee and the International Committee. Phildius recognized the importance of this

achievement and thanked Mott for his visit. Mott left Geneva having established better relations among the members

of the World's Committee.26

29

Mott returned to France and on April 24, and then accompanied American YMCA officials on a visit to Coblenz. They

inspected Association work for the American Army of Occupation assigned to this Rhine bridgehead. While in

Germany, Mott did not meet with any German YMCA officials. Instead, they drove through Belgium and northern

France, viewing the devastated countryside. Mott traveled to England in May, and finally returned to the

United States later that month.27

Mott returned to France and on April 24, and then accompanied American YMCA officials on a visit to Coblenz. They

inspected Association work for the American Army of Occupation assigned to this Rhine bridgehead. While in

Germany, Mott did not meet with any German YMCA officials. Instead, they drove through Belgium and northern

France, viewing the devastated countryside. Mott traveled to England in May, and finally returned to the

United States later that month.27

30

The major issue that upset the German YMCA and religious leadership was the future of German missionaries.

Before the war, the Germans had religious workers operating across Africa and India, but the Allies had captured

most of these missionaries and sent them to internment camps, eventually repatriating them to Germany. Karl

Axenfeld, one of the German Versailles Conference delegates representing the German missionary societies,

protested the Allied decision in April 1919 not to allow German missionaries to return to the former colonies. While

in England in May, Mott met with the Emergency Committee to review the German missionary situation.

They came to the conclusion that a more permanent organization was needed to address this issue. The members

asked Joseph Oldham to devote his full attention to German missionaries, and the English National YMCA released

him for this service. The members of the Emergency Committee also knew that they would have to approach German

missionary leaders very carefully, because these men were dejected and bitter. The Allies and neutral

organizations had temporarily taken over German overseas missions. Many Germans turned to Mott to rectify the

situation, because this missionary work had been the very lifeblood of many German churches-without foreign missions,

some churches would languish without purpose. The Germans believed they were cut off politically and economically,

surrounded by enemies, little better than moral pariahs.

The major issue that upset the German YMCA and religious leadership was the future of German missionaries.

Before the war, the Germans had religious workers operating across Africa and India, but the Allies had captured

most of these missionaries and sent them to internment camps, eventually repatriating them to Germany. Karl

Axenfeld, one of the German Versailles Conference delegates representing the German missionary societies,

protested the Allied decision in April 1919 not to allow German missionaries to return to the former colonies. While

in England in May, Mott met with the Emergency Committee to review the German missionary situation.

They came to the conclusion that a more permanent organization was needed to address this issue. The members

asked Joseph Oldham to devote his full attention to German missionaries, and the English National YMCA released

him for this service. The members of the Emergency Committee also knew that they would have to approach German

missionary leaders very carefully, because these men were dejected and bitter. The Allies and neutral

organizations had temporarily taken over German overseas missions. Many Germans turned to Mott to rectify the

situation, because this missionary work had been the very lifeblood of many German churches-without foreign missions,

some churches would languish without purpose. The Germans believed they were cut off politically and economically,

surrounded by enemies, little better than moral pariahs.

31

The Versailles Peace Treaty, signed in June 1919, eliminated German overseas missions, and many Germans protested

against this decision. The World's Alliance for Promoting Friendship Through the Churches met in Holland in October

1919 and called for the return of German missionaries to their overseas mission fields. Five German representatives