Table of Contents

Chapter 6

"In Prison, Ye Visited Me": The American YMCA Secretaries Initiate POW Relief in Germany

1

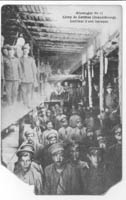

The American YMCA's decision to focus on relief services for war prisoners reflected many of the primary

objectives of the Association. The POW survived in a precarious situation. A burden to his captors but beyond

the assistance of his comrades, the POW became the "forgotten man" of the war. His captor's interests-whether

political, military, or social-did not promote prisoner welfare. Captor nations concentrated scarce national

resources into the war effort and the survival of their civilian populations, while the POW remained the

"enemy," a burden on the economy. This scenario was especially relevant for Allied prisoners languishing in

Central Power military prisons, since the Allied command imposed a blockade on Germany to deprive the empire

of needed raw materials. Therefore, prisoners, in their isolated position, were ideal candidates for the

ministrations of the YMCA. Red Triangle secretaries were motivated by the Biblical imperative to visit those

in prison: "In prison, Ye visited me…"1 The

Association leadership saw the Great War as a unique opportunity for the YMCA to meet a global need. As John

R. Mott pointed out in June 1916, the YMCA "under the current circumstances is having an opportunity under God

which will count more for the religious uplift of the world than any similar effort ever made."2 More importantly, the POW was a burden shared by all belligerents.

Assistance to war prisoners reflected the American YMCA's neutrality and bolstered the Wilson Administration's

foreign policy goal of dealing fairly and impartially with all of the nations at war.3

The American YMCA's decision to focus on relief services for war prisoners reflected many of the primary

objectives of the Association. The POW survived in a precarious situation. A burden to his captors but beyond

the assistance of his comrades, the POW became the "forgotten man" of the war. His captor's interests-whether

political, military, or social-did not promote prisoner welfare. Captor nations concentrated scarce national

resources into the war effort and the survival of their civilian populations, while the POW remained the

"enemy," a burden on the economy. This scenario was especially relevant for Allied prisoners languishing in

Central Power military prisons, since the Allied command imposed a blockade on Germany to deprive the empire

of needed raw materials. Therefore, prisoners, in their isolated position, were ideal candidates for the

ministrations of the YMCA. Red Triangle secretaries were motivated by the Biblical imperative to visit those

in prison: "In prison, Ye visited me…"1 The

Association leadership saw the Great War as a unique opportunity for the YMCA to meet a global need. As John

R. Mott pointed out in June 1916, the YMCA "under the current circumstances is having an opportunity under God

which will count more for the religious uplift of the world than any similar effort ever made."2 More importantly, the POW was a burden shared by all belligerents.

Assistance to war prisoners reflected the American YMCA's neutrality and bolstered the Wilson Administration's

foreign policy goal of dealing fairly and impartially with all of the nations at war.3

2

The American YMCA adopted a three-level strategy in meeting the needs of Allied prisoners and, in the process,

fulfilling the Association's mandate: to combat "barbed-wire disease," the boredom associated with languishing

without purpose in prison; to make incarceration a rewarding experience; and to gain access to new areas of the

world for future missions. While the American YMCA had gained some limited experience in providing welfare work

to prisoners through secretaries that visited inmates in American penitentiaries before the war, this was a new

mission field. Despite this, the Association's four-fold program could be modified by secretaries to meet the

conditions in specific POW compounds.

The American YMCA adopted a three-level strategy in meeting the needs of Allied prisoners and, in the process,

fulfilling the Association's mandate: to combat "barbed-wire disease," the boredom associated with languishing

without purpose in prison; to make incarceration a rewarding experience; and to gain access to new areas of the

world for future missions. While the American YMCA had gained some limited experience in providing welfare work

to prisoners through secretaries that visited inmates in American penitentiaries before the war, this was a new

mission field. Despite this, the Association's four-fold program could be modified by secretaries to meet the

conditions in specific POW compounds.

3

The primary objective was to provide welfare relief to "save" war prisoners from "barbed-wire disease."

This condition progressed as the prisoner languished in captivity. Its chief causes were insufficient diet,

poor sanitary conditions, and most importantly, the daily monotony of the prison routine. To combat this

condition, the American secretaries instituted the four-fold YMCA program, which stressed physical, mental,

social, and spiritual relief. Red Triangle workers reduced camp monotony by offering inmates diversions and

instilling a sense of hope that they would eventually be reunited with their families. Over time, as conditions

in Central European prisons deteriorated, this strategy evolved to simply looking after the survival of Allied

prisoners.4

The primary objective was to provide welfare relief to "save" war prisoners from "barbed-wire disease."

This condition progressed as the prisoner languished in captivity. Its chief causes were insufficient diet,

poor sanitary conditions, and most importantly, the daily monotony of the prison routine. To combat this

condition, the American secretaries instituted the four-fold YMCA program, which stressed physical, mental,

social, and spiritual relief. Red Triangle workers reduced camp monotony by offering inmates diversions and

instilling a sense of hope that they would eventually be reunited with their families. Over time, as conditions

in Central European prisons deteriorated, this strategy evolved to simply looking after the survival of Allied

prisoners.4

4

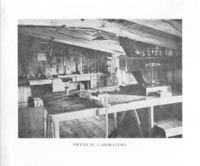

The first element of the Association program developed the prisoner's physical condition. Secretaries

encouraged POWs to stay in good shape through exercise and competitive sports. The YMCA improved sanitation

facilities (showers, baths, water purification, and delousing plants) and medical resources (dental and

disinfectant equipment, medical supplies, and infirmaries) to prevent the physical deterioration of prison

populations. Second, the Association's program emphasized sound mental health through projects designed to

break the camp's monotony.

The first element of the Association program developed the prisoner's physical condition. Secretaries

encouraged POWs to stay in good shape through exercise and competitive sports. The YMCA improved sanitation

facilities (showers, baths, water purification, and delousing plants) and medical resources (dental and

disinfectant equipment, medical supplies, and infirmaries) to prevent the physical deterioration of prison

populations. Second, the Association's program emphasized sound mental health through projects designed to

break the camp's monotony.

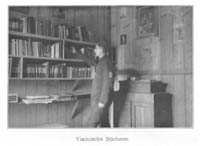

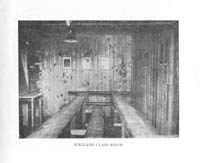

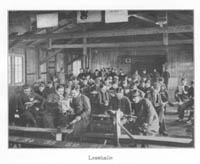

The secretaries set up a wide range of activities, including extensive libraries in numerous languages, arts and crafts materials, and schools that ranged from

remedial reading and arithmetic to university courses. The third element, closely aligned with the second,

was social development. The YMCA supplied musical instruments and sheet music to POWs to form orchestras, bands, and choirs, and the Association supported theatrical productions by sending scripts, costumes, and stages.

The secretaries set up a wide range of activities, including extensive libraries in numerous languages, arts and crafts materials, and schools that ranged from

remedial reading and arithmetic to university courses. The third element, closely aligned with the second,

was social development. The YMCA supplied musical instruments and sheet music to POWs to form orchestras, bands, and choirs, and the Association supported theatrical productions by sending scripts, costumes, and stages.

The Association

also set up prisoner information bureaus to provide prisoners and their families with some measure of

emotional relief by locating prisoners and establishing contact. Prisoners were able to receive food

parcels or money, which became essential to supplement their meager diets.5

The Association

also set up prisoner information bureaus to provide prisoners and their families with some measure of

emotional relief by locating prisoners and establishing contact. Prisoners were able to receive food

parcels or money, which became essential to supplement their meager diets.5

5

The final element of the POW program focused on the spiritual needs of the prisoners, by providing places

of worship and religious services. The Association tried to provide prisoners with clergymen of their own

faiths by transferring captured chaplains to camps with underserved spiritual needs. If captive chaplains

were unavailable, secretaries worked to persuade local clergy to visit prison camps and perform services.

The YMCA also provided such religious articles as vestments for ministers, special kosher foods, and blessed

altar cloths for Orthodox services. In addition, the Association made special efforts to make sure prisoners

had a merry Christmas, especially since POWs felt especially vulnerable separated from family and friends.

Secretaries decorated the huts, provided Christmas trees, and worked to make sure that even the poorest

prisoners received a small gift.6

The final element of the POW program focused on the spiritual needs of the prisoners, by providing places

of worship and religious services. The Association tried to provide prisoners with clergymen of their own

faiths by transferring captured chaplains to camps with underserved spiritual needs. If captive chaplains

were unavailable, secretaries worked to persuade local clergy to visit prison camps and perform services.

The YMCA also provided such religious articles as vestments for ministers, special kosher foods, and blessed

altar cloths for Orthodox services. In addition, the Association made special efforts to make sure prisoners

had a merry Christmas, especially since POWs felt especially vulnerable separated from family and friends.

Secretaries decorated the huts, provided Christmas trees, and worked to make sure that even the poorest

prisoners received a small gift.6

6

The second, and far more ambitious, goal of the YMCA was to make the war prisoners' incarceration rewarding.

By making the most of their prison confinement, each man would return home with enhanced skills that would

benefit the individual, his family, and society. This objective was reached through programs in education,

occupational training, and physical rehabilitation. Secretaries worked especially hard to establish school

systems in camps whenever possible. They recruited teachers from among the prisoners and offered wide-ranging

curricula. The Association designed university-level classes for college students, especially among the German,

French, and English inmates who had been drafted or recruited before they completed their degrees. The YMCA

set up extension classes with local colleges by recruiting faculty volunteers. At the other extreme, the

Association organized remedial reading courses for illiterate prisoners (approximately 80 percent of the Russian

and Serbian POWs could not read). Secretaries taught these inmates the alphabet and primary reading skills. In

addition, the YMCA established schools for boys, especially in Austria-Hungary, because large numbers of juveniles

followed their fathers into combat and were captured. They made special efforts to protect these boys, isolating

them from the general prison population and transferring them to central camps where they could receive an

education.7

The second, and far more ambitious, goal of the YMCA was to make the war prisoners' incarceration rewarding.

By making the most of their prison confinement, each man would return home with enhanced skills that would

benefit the individual, his family, and society. This objective was reached through programs in education,

occupational training, and physical rehabilitation. Secretaries worked especially hard to establish school

systems in camps whenever possible. They recruited teachers from among the prisoners and offered wide-ranging

curricula. The Association designed university-level classes for college students, especially among the German,

French, and English inmates who had been drafted or recruited before they completed their degrees. The YMCA

set up extension classes with local colleges by recruiting faculty volunteers. At the other extreme, the

Association organized remedial reading courses for illiterate prisoners (approximately 80 percent of the Russian

and Serbian POWs could not read). Secretaries taught these inmates the alphabet and primary reading skills. In

addition, the YMCA established schools for boys, especially in Austria-Hungary, because large numbers of juveniles

followed their fathers into combat and were captured. They made special efforts to protect these boys, isolating

them from the general prison population and transferring them to central camps where they could receive an

education.7

7

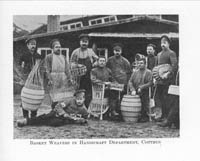

Occupational training was an extension of the educational service of the YMCA. POWs learned skilled trades that

would increase their earning potential after the war. Many camps opened tanneries, tailor shops, book-binderies,

carpentry shops, shoe shops, and blacksmith foundries.

Occupational training was an extension of the educational service of the YMCA. POWs learned skilled trades that

would increase their earning potential after the war. Many camps opened tanneries, tailor shops, book-binderies,

carpentry shops, shoe shops, and blacksmith foundries.

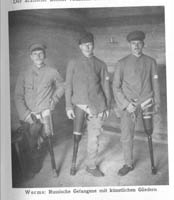

These shops also served a secondary, economic function: many of their products were in great demand and consumed

directly in the prison camps, or sold outside to provide industrious POWs with additional income. A special

target group was wounded and crippled prisoners. Secretaries encouraged amputees, who would be unable to return

to their pre-war occupations, to learn new trades so that they would not become a burden on their families and

society after their release. For example, the YMCA set up a special rehabilitation center at Wieselburg in

Hungary to help retrain trauma victims to ease their transition to civilian life.8

These shops also served a secondary, economic function: many of their products were in great demand and consumed

directly in the prison camps, or sold outside to provide industrious POWs with additional income. A special

target group was wounded and crippled prisoners. Secretaries encouraged amputees, who would be unable to return

to their pre-war occupations, to learn new trades so that they would not become a burden on their families and

society after their release. For example, the YMCA set up a special rehabilitation center at Wieselburg in

Hungary to help retrain trauma victims to ease their transition to civilian life.8

8

The last objective of the American YMCA was internally driven. The Association, through its work with POWs,

hoped to improve its reputation to gain access to areas of the world, which had previously resisted its entry.

These areas were primarily non-Protestant nations that were reluctant to authorize foreign missions by the

International Committee. Secretaries hoped to recruit future secretaries from the POW populations through the

Association program. These recruits would learn as much as they could about the YMCA during their incarceration

and return home to establish chapters. A more realistic goal was simply establishing name recognition among the

war prisoners. After the war, former POWs might be more receptive to YMCA missions, especially if the Association

had rendered them a valuable service during their captivity. Simultaneously, the YMCA got the chance to

demonstrate its humanitarian services to belligerent governments that had previously resisted the establishment

of Associations. These future missionary fields included Orthodox and Muslim countries, particularly Russia,

Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey, as well as Catholic countries such as France and Italy. War prisoner

service was a potential new force in the post-war expansion of Association work.9

The last objective of the American YMCA was internally driven. The Association, through its work with POWs,

hoped to improve its reputation to gain access to areas of the world, which had previously resisted its entry.

These areas were primarily non-Protestant nations that were reluctant to authorize foreign missions by the

International Committee. Secretaries hoped to recruit future secretaries from the POW populations through the

Association program. These recruits would learn as much as they could about the YMCA during their incarceration

and return home to establish chapters. A more realistic goal was simply establishing name recognition among the

war prisoners. After the war, former POWs might be more receptive to YMCA missions, especially if the Association

had rendered them a valuable service during their captivity. Simultaneously, the YMCA got the chance to

demonstrate its humanitarian services to belligerent governments that had previously resisted the establishment

of Associations. These future missionary fields included Orthodox and Muslim countries, particularly Russia,

Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey, as well as Catholic countries such as France and Italy. War prisoner

service was a potential new force in the post-war expansion of Association work.9

Harte Inaugurates Relief Work in Germany

9

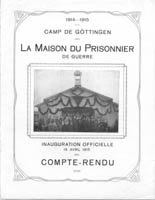

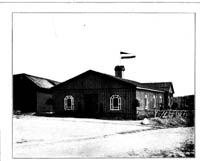

On 29 March 1915, ground was broken at Göttingen for the first YMCA war prison "hut" in the world.

Work on the building began on March 15, when Archibald C. Harte signed the contract for the lumber and

supplies. This building (measuring thirty feet by ninety feet) included a veranda, a small clock tower, a large

room (thirty feet by sixty feet), a library alcove, a smaller room (fifteen feet by twenty-four feet) for lectures, choir, or

orchestra rehearsals, and three small rooms for classes. The hut served as the social, educational, and

religious center of the camp. It cost the American YMCA six thousand Marks to construct, or fifteen cents per

inmate. The prisoners provided the labor for the construction and carpentry work. The hut was scheduled

for completion on April 15, when its formal inauguration would be celebrated.10

On 29 March 1915, ground was broken at Göttingen for the first YMCA war prison "hut" in the world.

Work on the building began on March 15, when Archibald C. Harte signed the contract for the lumber and

supplies. This building (measuring thirty feet by ninety feet) included a veranda, a small clock tower, a large

room (thirty feet by sixty feet), a library alcove, a smaller room (fifteen feet by twenty-four feet) for lectures, choir, or

orchestra rehearsals, and three small rooms for classes. The hut served as the social, educational, and

religious center of the camp. It cost the American YMCA six thousand Marks to construct, or fifteen cents per

inmate. The prisoners provided the labor for the construction and carpentry work. The hut was scheduled

for completion on April 15, when its formal inauguration would be celebrated.10

10

The establishment of an Association hut at Crossen-an-der-Oder was also in progress at the same time.

Harte ordered equipment for the reading room, which included fifty board tables, two hundred benches,

a map, a clock, a blackboard, and a small library. Relief work at this camp would focus on the welfare

of Russian POWs. An inauguration ceremony would follow in April.11

The establishment of an Association hut at Crossen-an-der-Oder was also in progress at the same time.

Harte ordered equipment for the reading room, which included fifty board tables, two hundred benches,

a map, a clock, a blackboard, and a small library. Relief work at this camp would focus on the welfare

of Russian POWs. An inauguration ceremony would follow in April.11

11

While construction proceeded at Göttingen, Harte worked with the POWs. He preached before a packed

barrack room and, although there were no hymn-books, the singing was enthusiastic. After the service,

Harte met with the non-commissioned officers who would supervise the new organization. They agreed that

the prisoners who wished to become members should pay a monthly fifteen Pfennig fee (the Association firmly

believed that free services were never appreciated and enjoyed as much as paid services; even a small fee

was important, since it helped members feel that they were contributing to their own welfare program). They

also made plans for an English, French, and Russian library, choirs, an orchestra, and a school. Professor

Carl Stange, of the University of Göttingen, agreed to teach a German class composed of twenty-one

sergeants; they would then teach the enlisted men. Eventually, classes in French and Russian would follow.

Harte planned the English library, well stocked with religious works. He obtained five hundred hymnals, one thousand

Testaments and Bibles, simple Bible study books, a Bible dictionary, a commentary, and other general books.

Harte purchased similar materials in other languages as they became available.

While construction proceeded at Göttingen, Harte worked with the POWs. He preached before a packed

barrack room and, although there were no hymn-books, the singing was enthusiastic. After the service,

Harte met with the non-commissioned officers who would supervise the new organization. They agreed that

the prisoners who wished to become members should pay a monthly fifteen Pfennig fee (the Association firmly

believed that free services were never appreciated and enjoyed as much as paid services; even a small fee

was important, since it helped members feel that they were contributing to their own welfare program). They

also made plans for an English, French, and Russian library, choirs, an orchestra, and a school. Professor

Carl Stange, of the University of Göttingen, agreed to teach a German class composed of twenty-one

sergeants; they would then teach the enlisted men. Eventually, classes in French and Russian would follow.

Harte planned the English library, well stocked with religious works. He obtained five hundred hymnals, one thousand

Testaments and Bibles, simple Bible study books, a Bible dictionary, a commentary, and other general books.

Harte purchased similar materials in other languages as they became available.

As soon as the building was opened, the American YMCA would send additional equipment. Harte requested that

the International Committee send all possible news, including programs, menus, and photographs (which could

quickly pass through German censors). He also acquired a piano, a harmonium, tables, benches, blackboards,

maps, and pictures to support the educational program. He felt that the organization also required carbolic

soap, tinned meats, fruit, cheese, socks, shoes, underwear, biscuits, preserved fruits, chocolate, and tobacco.

In addition, the commandant approved the erection of a monument to the dead in the camp cemetery. Funds for

the construction came from the prisoners.12

As soon as the building was opened, the American YMCA would send additional equipment. Harte requested that

the International Committee send all possible news, including programs, menus, and photographs (which could

quickly pass through German censors). He also acquired a piano, a harmonium, tables, benches, blackboards,

maps, and pictures to support the educational program. He felt that the organization also required carbolic

soap, tinned meats, fruit, cheese, socks, shoes, underwear, biscuits, preserved fruits, chocolate, and tobacco.

In addition, the commandant approved the erection of a monument to the dead in the camp cemetery. Funds for

the construction came from the prisoners.12

12

With permission from the Germans to begin Association work in prison camps, Harte had to establish an

organization to supervise operations. The World's Committee of the World's Alliance of YMCAs recommended that

POW work be undertaken by Swiss secretaries. The English National YMCA Council opposed this plan, however,

unless these secretaries worked directly under their jurisdiction. The International Committee in New York

initially supported having American secretaries work under the auspices of the World's Committee to emphasize

the neutral and international character of POW relief. The initial agreements between Mott and several members

of the World's Committee in early 1915 reflected the American YMCA's willingness to work under the World's

Alliance, but Harte determined this might create political problems. He concluded that German authorities were

suspicious of the neutral spirit of the World's Committee, and the German National YMCA Council expressed

reservations about working with the Geneva-based group. As a result, Harte recommended that the International

Committee send money and assign personnel under the jurisdiction of the national

YMCA Councils in each country. Association secretaries from these countries could freely enter prison camps, and

they would provide a service to their enemies, which would be appreciated after the war and improve international

relations. The national YMCA Council in each country would undertake relief work for POWs

where the authorities agreed to grant access to war prison camps. If a given national Council could not support

this work, especially if there were financial constraints, then the work should be organized as an affiliated

service to the national YMCA Council. In this event, the work would be assigned to the World's Committee, but under the purview of a

special sub-committee working under an international umbrella organization. In each country, Mott felt, POW

relief should be supervised by a small committee appointed by the chairman of the national YMCA Council and

the work supervised by a trained Red Triangle secretary. Wherever possible, Association workers should be citizens or

subjects of the country in which they worked, and any neutral secretaries had to receive full approval from

the Ministry of War of that country. This organizational plan had promise in theory, but would have to be

modified in practice.13

With permission from the Germans to begin Association work in prison camps, Harte had to establish an

organization to supervise operations. The World's Committee of the World's Alliance of YMCAs recommended that

POW work be undertaken by Swiss secretaries. The English National YMCA Council opposed this plan, however,

unless these secretaries worked directly under their jurisdiction. The International Committee in New York

initially supported having American secretaries work under the auspices of the World's Committee to emphasize

the neutral and international character of POW relief. The initial agreements between Mott and several members

of the World's Committee in early 1915 reflected the American YMCA's willingness to work under the World's

Alliance, but Harte determined this might create political problems. He concluded that German authorities were

suspicious of the neutral spirit of the World's Committee, and the German National YMCA Council expressed

reservations about working with the Geneva-based group. As a result, Harte recommended that the International

Committee send money and assign personnel under the jurisdiction of the national

YMCA Councils in each country. Association secretaries from these countries could freely enter prison camps, and

they would provide a service to their enemies, which would be appreciated after the war and improve international

relations. The national YMCA Council in each country would undertake relief work for POWs

where the authorities agreed to grant access to war prison camps. If a given national Council could not support

this work, especially if there were financial constraints, then the work should be organized as an affiliated

service to the national YMCA Council. In this event, the work would be assigned to the World's Committee, but under the purview of a

special sub-committee working under an international umbrella organization. In each country, Mott felt, POW

relief should be supervised by a small committee appointed by the chairman of the national YMCA Council and

the work supervised by a trained Red Triangle secretary. Wherever possible, Association workers should be citizens or

subjects of the country in which they worked, and any neutral secretaries had to receive full approval from

the Ministry of War of that country. This organizational plan had promise in theory, but would have to be

modified in practice.13

13

Harte's decision to set up POW relief committees through national YMCA Councils rather than under the auspices

of the World's Alliance of YMCAs led to a serious disagreement with Christian Phildius. The World's Committee

General Secretary wrote to Mott about the disagreement in April 1915. Friction between the two Association

secretaries began in March, when the World's Committee published an article that incorrectly stated that Harte

had been sent to Germany to work solely with British POWs. Harte responded with a strong letter of protest,

since such reporting undermined his bargaining position with the Russian and Austro-Hungarian governments.

Phildius concluded that Harte was firmly under the strong influence of Gerhard Niedermeyer, the National

Secretary of the German Student Christian Movement. As a result, Harte had placed POW relief work into the

hands of the German National YMCA Committee, excluding the World's Committee, which seriously weakened the

Geneva organization. More importantly, Phildius believed Niedermeyer was "not internationally inclined," which

augmented the problem. Instead, Phildius praised Carlisle V. Hibbard, because he "worked harmoniously with the

World's Committee." This marked the beginning of a rift between Harte and the World's Alliance, since Harte

declined to travel to Geneva to address the misunderstanding. This disagreement would continue to fester, and

expanded tremendously after the U.S. entered the war.14

Harte's decision to set up POW relief committees through national YMCA Councils rather than under the auspices

of the World's Alliance of YMCAs led to a serious disagreement with Christian Phildius. The World's Committee

General Secretary wrote to Mott about the disagreement in April 1915. Friction between the two Association

secretaries began in March, when the World's Committee published an article that incorrectly stated that Harte

had been sent to Germany to work solely with British POWs. Harte responded with a strong letter of protest,

since such reporting undermined his bargaining position with the Russian and Austro-Hungarian governments.

Phildius concluded that Harte was firmly under the strong influence of Gerhard Niedermeyer, the National

Secretary of the German Student Christian Movement. As a result, Harte had placed POW relief work into the

hands of the German National YMCA Committee, excluding the World's Committee, which seriously weakened the

Geneva organization. More importantly, Phildius believed Niedermeyer was "not internationally inclined," which

augmented the problem. Instead, Phildius praised Carlisle V. Hibbard, because he "worked harmoniously with the

World's Committee." This marked the beginning of a rift between Harte and the World's Alliance, since Harte

declined to travel to Geneva to address the misunderstanding. This disagreement would continue to fester, and

expanded tremendously after the U.S. entered the war.14

14

On 3 April 1915, Harte returned to Berlin for a conference of German officials and began to organize POW

relief work. At this initial meeting, he met with a member of the Ministry of War and three professors from

Göttingen, Hannoverisch-Münden, and Cassel. This group had studied the POW system in Germany with

a goal of making improvements. Caring for almost one million war prisoners taxed the German economy. The Germans

had to guard, house, clothe, and feed these men, along with providing essential services such as post offices,

hospitals, baths, laundries, bakeries, tailors, shoemakers, ministers, and priests. Harte was convinced that

these men were striving to improve the situation of Allied POWs in a genuinely

On 3 April 1915, Harte returned to Berlin for a conference of German officials and began to organize POW

relief work. At this initial meeting, he met with a member of the Ministry of War and three professors from

Göttingen, Hannoverisch-Münden, and Cassel. This group had studied the POW system in Germany with

a goal of making improvements. Caring for almost one million war prisoners taxed the German economy. The Germans

had to guard, house, clothe, and feed these men, along with providing essential services such as post offices,

hospitals, baths, laundries, bakeries, tailors, shoemakers, ministers, and priests. Harte was convinced that

these men were striving to improve the situation of Allied POWs in a genuinely

humanitarian spirit. This group also wished to advance "real German Kultur" to these men to disseminate

German ideas among the POWs. While somewhat suspicious of this objective, Harte presented the discussion in the

best possible light in his reports. By May 1915, Harte and the German YMCA had organized POW relief work on a

more formal basis. The National Committee of the German YMCA had set up a Prisoner of War Committee to supervise

relief work in the prison camps. G. Rosenkranz, a factory owner from Barmen, served as president of this committee.

Other members included Pastor Berlin as vice president; Meyer as secretary; Captain W. von Lübbers as the

Ministry of War representative; Niedermeyer of the German Student Christian Movement; and Harte. This committee,

the War Prisoners' Aid of the YMCA (WPA), secured patrons to support POW relief work, collect books, study

additional avenues of work, and assist prisoners wherever possible. The German YMCA provided an office for the

WPA headquarters in Berlin.15

humanitarian spirit. This group also wished to advance "real German Kultur" to these men to disseminate

German ideas among the POWs. While somewhat suspicious of this objective, Harte presented the discussion in the

best possible light in his reports. By May 1915, Harte and the German YMCA had organized POW relief work on a

more formal basis. The National Committee of the German YMCA had set up a Prisoner of War Committee to supervise

relief work in the prison camps. G. Rosenkranz, a factory owner from Barmen, served as president of this committee.

Other members included Pastor Berlin as vice president; Meyer as secretary; Captain W. von Lübbers as the

Ministry of War representative; Niedermeyer of the German Student Christian Movement; and Harte. This committee,

the War Prisoners' Aid of the YMCA (WPA), secured patrons to support POW relief work, collect books, study

additional avenues of work, and assist prisoners wherever possible. The German YMCA provided an office for the

WPA headquarters in Berlin.15

15

By April 13, Harte had the beginnings of a POW relief program well established in Germany. Work was about

to begin at Göttingen, primarily for French and Belgian prisoners; it was well under way at

Crossen-an-der-Oder for Russian POWs; and was planned for Allied prisoners at Hannoverisch-Münden. The

American secretary also planned operations at the POW camp at Sennelager for British POWs. German YMCA workers

were free to enter prison camps, and enthusiastically provided services for Allied POWs. This work, it was hoped,

would help restore amity between nations after the war, as Germans aided Englishmen, Belgians, Frenchmen, and

Russians in prison camps. This work grew out of the ideology of Christian Internationalism, which advocated that

national barriers be broken down to extend service to one's fellow men.16

By April 13, Harte had the beginnings of a POW relief program well established in Germany. Work was about

to begin at Göttingen, primarily for French and Belgian prisoners; it was well under way at

Crossen-an-der-Oder for Russian POWs; and was planned for Allied prisoners at Hannoverisch-Münden. The

American secretary also planned operations at the POW camp at Sennelager for British POWs. German YMCA workers

were free to enter prison camps, and enthusiastically provided services for Allied POWs. This work, it was hoped,

would help restore amity between nations after the war, as Germans aided Englishmen, Belgians, Frenchmen, and

Russians in prison camps. This work grew out of the ideology of Christian Internationalism, which advocated that

national barriers be broken down to extend service to one's fellow men.16

The Inauguration of the Association Building at Göttingen

16

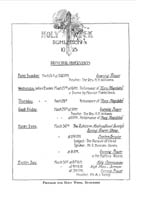

American YMCA POW work officially began on 15 April 1915, when the Association hut was inaugurated at

Göttingen. Ambassador James W. Gerard, Vincente Palmaroli (the Spanish consul representing the ambassador),

Dr. Karl Ohnesorg (U.S. Naval Attaché), Meyer (Director of the National Committee of the YMCAs of Germany),

Niedermeyer (General Secretary of the German Christian Student Movement), Professor Stange, Reverend A. W.

Schreiber, Phildius, and Harte plus many other pastors, professors, and

American YMCA POW work officially began on 15 April 1915, when the Association hut was inaugurated at

Göttingen. Ambassador James W. Gerard, Vincente Palmaroli (the Spanish consul representing the ambassador),

Dr. Karl Ohnesorg (U.S. Naval Attaché), Meyer (Director of the National Committee of the YMCAs of Germany),

Niedermeyer (General Secretary of the German Christian Student Movement), Professor Stange, Reverend A. W.

Schreiber, Phildius, and Harte plus many other pastors, professors, and

Christian workers attended the official opening of the YMCA building, making the occasion an international event. American and

Spanish diplomatic officials participated as representatives of the Allied nations. But more importantly,

Harte's speech focused on the opportunities such a facility presented for Christian Internationalism, a

"world-wide brotherhood of young men." Through the joint effort of the Ministry of War, the German YMCA

National Committee, and the American YMCA, this building was dedicated: "…for the young men of Belgium,

Flanders, France, Great Britain, and Russia, [and] is a witness of a relation that lies deeper than race,

nationality, and circumstances."17

Christian workers attended the official opening of the YMCA building, making the occasion an international event. American and

Spanish diplomatic officials participated as representatives of the Allied nations. But more importantly,

Harte's speech focused on the opportunities such a facility presented for Christian Internationalism, a

"world-wide brotherhood of young men." Through the joint effort of the Ministry of War, the German YMCA

National Committee, and the American YMCA, this building was dedicated: "…for the young men of Belgium,

Flanders, France, Great Britain, and Russia, [and] is a witness of a relation that lies deeper than race,

nationality, and circumstances."17

17 Harte warned that:

No man can leave this war prison the same man that he entered. Every man here will either acquire or strengthen habits of idleness and daily deteriorate, and, when peace is declared, go out slouching and growling a ruined man, asking to be taken care of by his country, his friends, or even by his mother or siblings; or he will acquire or strengthen habits of seeking knowledge, of serving his fellowmen, and of making friends that will so enrich him, that he will go out to be in a new sense a benefactor of his home, his country, and his generation.18

18

The American secretary urged the prisoners to use this center to develop a commitment to culture, service,

and friendship. In their leisure time, they could appreciate new cultures by acquiring new languages; study

the manners, customs, and histories of other people; and learn new arts and skills. The Association hut

offered a library, musical instruments, study and conference rooms, and a hall for sermons, lectures, and

concerts, which (it was hoped) would help the POWs understand the expanded cultural offerings that were now

available to them. POWs were to develop the habit of thinking first of the needs of their companions and

The American secretary urged the prisoners to use this center to develop a commitment to culture, service,

and friendship. In their leisure time, they could appreciate new cultures by acquiring new languages; study

the manners, customs, and histories of other people; and learn new arts and skills. The Association hut

offered a library, musical instruments, study and conference rooms, and a hall for sermons, lectures, and

concerts, which (it was hoped) would help the POWs understand the expanded cultural offerings that were now

available to them. POWs were to develop the habit of thinking first of the needs of their companions and

learning how to meet those needs, "For the man who had learned this lesson and practiced it cannot be

unhappy, and must daily attain unto the stature of the perfect man." Finally, service was described as

being "the royal way to friendship, for the man who thinks most of others and serves most will have the

most friends." By making friends with companions, officers, and guards, POWs would discover the bright side

of life in a war prison. This philosophy was the foundation of the Association's POW relief service; that

captivity should not be wasted in self-pity, but instead viewed as an opportunity for POWs to learn new

trades, develop better skills, and take advantage of educational opportunities. Not only would they benefit

as individuals, but they also had a chance to help their communities when they returned home.19

learning how to meet those needs, "For the man who had learned this lesson and practiced it cannot be

unhappy, and must daily attain unto the stature of the perfect man." Finally, service was described as

being "the royal way to friendship, for the man who thinks most of others and serves most will have the

most friends." By making friends with companions, officers, and guards, POWs would discover the bright side

of life in a war prison. This philosophy was the foundation of the Association's POW relief service; that

captivity should not be wasted in self-pity, but instead viewed as an opportunity for POWs to learn new

trades, develop better skills, and take advantage of educational opportunities. Not only would they benefit

as individuals, but they also had a chance to help their communities when they returned home.19

19

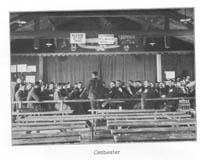

The program included performances by the camp's newly organized choir and orchestra, as well as speeches by

Colonel Bogen, Harte, Stange, and British, French, and Belgian prisoners. Then the Association building was

officially declared open, and

The program included performances by the camp's newly organized choir and orchestra, as well as speeches by

Colonel Bogen, Harte, Stange, and British, French, and Belgian prisoners. Then the Association building was

officially declared open, and

the Association's work could begin. Stange had already enlisted other professors at the University of

Göttingen to offer classes to the POWs. They gave lectures, organized courses, and contributed to the

camp library. The prisoners also began a garden in front of the building. As Harte observed, "the chief

charm of the whole affair was the sense of ownership and comradeship constantly in evidence."20

the Association's work could begin. Stange had already enlisted other professors at the University of

Göttingen to offer classes to the POWs. They gave lectures, organized courses, and contributed to the

camp library. The prisoners also began a garden in front of the building. As Harte observed, "the chief

charm of the whole affair was the sense of ownership and comradeship constantly in evidence."20

20

The Wilson Administration's strong support for the American YMCA's POW relief work in Germany was clear after

the Göttingen inauguration. Ambassador Gerard enthusiastically supported Harte's work and readily accepted

the YMCA's invitation to participate in the Göttingen ceremony. Gerard even attempted to persuade the

Spanish ambassador to accompany him to the inauguration to add even more diplomatic prestige. In letters to

Mott, the U.S. Ambassador praised the hard work and effort Harte put into his mission. Gerard declared: "I

congratulate you on the idea and hope that you and your American friends will extend this work to the prison

camps throughout the world."21 After the hut was

opened, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan cabled the International Committee to congratulate the

American YMCA on its efforts to aid Allied POWs. Bryan described this work as being "of inestimable

The Wilson Administration's strong support for the American YMCA's POW relief work in Germany was clear after

the Göttingen inauguration. Ambassador Gerard enthusiastically supported Harte's work and readily accepted

the YMCA's invitation to participate in the Göttingen ceremony. Gerard even attempted to persuade the

Spanish ambassador to accompany him to the inauguration to add even more diplomatic prestige. In letters to

Mott, the U.S. Ambassador praised the hard work and effort Harte put into his mission. Gerard declared: "I

congratulate you on the idea and hope that you and your American friends will extend this work to the prison

camps throughout the world."21 After the hut was

opened, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan cabled the International Committee to congratulate the

American YMCA on its efforts to aid Allied POWs. Bryan described this work as being "of inestimable  value" and hoped that similar relief operations could be extended to all prison camps. Both Gerard and Bryan

forwarded Harte's reports from Germany through diplomatic channels. In addition, Gerard sent photographs taken

by Harte of German prison camps. German military censors approved the photos for publication in American

magazines and newspapers, which gave the YMCA program even greater publicity. Harte was adept at using

photography-and even motion pictures-to portray prison life, and to highlight ways that the Association could

improve POW living standards. From the State Department's perspective, the American YMCA's humanitarian efforts

for POWs of all nations strengthened the United States' neutrality policy, and effectively counter-balanced

growing German criticism of American munitions sales to the Allies, war loan negotiations, and British

interception of foreign mail.22

value" and hoped that similar relief operations could be extended to all prison camps. Both Gerard and Bryan

forwarded Harte's reports from Germany through diplomatic channels. In addition, Gerard sent photographs taken

by Harte of German prison camps. German military censors approved the photos for publication in American

magazines and newspapers, which gave the YMCA program even greater publicity. Harte was adept at using

photography-and even motion pictures-to portray prison life, and to highlight ways that the Association could

improve POW living standards. From the State Department's perspective, the American YMCA's humanitarian efforts

for POWs of all nations strengthened the United States' neutrality policy, and effectively counter-balanced

growing German criticism of American munitions sales to the Allies, war loan negotiations, and British

interception of foreign mail.22

21

With access to German prison camps, Harte put the next step of the Association program into effect. Trained

YMCA secretaries needed to be assigned to visit prison camps, to organize committees, and to support relief

operations. Since he was still negotiating with belligerent governments, Harte requested the International

Committee dispatch German-speaking American secretaries for work in Germany. Through the U.S. embassy, Harte

asked for two secretaries for immediate work. One would supervise shipments and correspondence, while the

other would conduct field-work among POWs. Harte hoped that two or three workers would be in Germany by

August to get relief operations underway.23

With access to German prison camps, Harte put the next step of the Association program into effect. Trained

YMCA secretaries needed to be assigned to visit prison camps, to organize committees, and to support relief

operations. Since he was still negotiating with belligerent governments, Harte requested the International

Committee dispatch German-speaking American secretaries for work in Germany. Through the U.S. embassy, Harte

asked for two secretaries for immediate work. One would supervise shipments and correspondence, while the

other would conduct field-work among POWs. Harte hoped that two or three workers would be in Germany by

August to get relief operations underway.23

22

Before Harte departed on his second trip to Russia, he visited the British civilian internment camp at

Ruhleben in September 1915. He was able to inspect the camp and freely talk with the prisoners, whom he

found "in good health and had no desires that I could gratify." The prison grounds were large, and the

internees had access to excellent athletic facilities; in addition, the camp featured a good canteen, and

the POWs had established several social organizations. The prisoners had an orchestra, dramatic club,

choir, weekly church services, and a large library. The camp school system had 1,200 prisoners enrolled in

150 classes. Harte asked the military authorities to construct a large Association hut for social and

educational programs. The commandant immediately granted the request, and the building was swiftly erected.

It became the social center of the prison, and many inmates survived the war by participating in the Association

program.24

Before Harte departed on his second trip to Russia, he visited the British civilian internment camp at

Ruhleben in September 1915. He was able to inspect the camp and freely talk with the prisoners, whom he

found "in good health and had no desires that I could gratify." The prison grounds were large, and the

internees had access to excellent athletic facilities; in addition, the camp featured a good canteen, and

the POWs had established several social organizations. The prisoners had an orchestra, dramatic club,

choir, weekly church services, and a large library. The camp school system had 1,200 prisoners enrolled in

150 classes. Harte asked the military authorities to construct a large Association hut for social and

educational programs. The commandant immediately granted the request, and the building was swiftly erected.

It became the social center of the prison, and many inmates survived the war by participating in the Association

program.24

23

In late September 1915, the Ministry of War approved Harte's request for four neutral secretaries to begin

welfare operations in Germany and announced that they would accept additional secretaries. The theoretical

organizational plan Harte had developed in March 1915 had problems in application. Under the original plan,

WPA work would be carried out by national YMCA Committees employing secretaries from their respective countries.

But Harte and Hibbard realized that it would be impossible to win the confidence of the British and French

governments if reports about prison camp conditions in Germany were written by German Association secretaries.

The German government would find reports written by English or French secretaries equally suspicious. Only the

absolute neutrality of American secretaries and the reciprocal program of the American YMCA mission could lend

credibility to these reports. As a result, the American YMCA needed American and other neutral secretaries to

enact the WPA program.25

In late September 1915, the Ministry of War approved Harte's request for four neutral secretaries to begin

welfare operations in Germany and announced that they would accept additional secretaries. The theoretical

organizational plan Harte had developed in March 1915 had problems in application. Under the original plan,

WPA work would be carried out by national YMCA Committees employing secretaries from their respective countries.

But Harte and Hibbard realized that it would be impossible to win the confidence of the British and French

governments if reports about prison camp conditions in Germany were written by German Association secretaries.

The German government would find reports written by English or French secretaries equally suspicious. Only the

absolute neutrality of American secretaries and the reciprocal program of the American YMCA mission could lend

credibility to these reports. As a result, the American YMCA needed American and other neutral secretaries to

enact the WPA program.25

The First American Secretaries Enter the Field in Germany

24

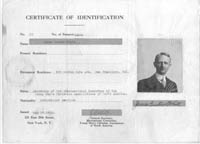

When Conrad Hoffman entered the field in September 1915, he was the pioneer of WPA work in Germany. He

received a Ministry of War permit-signed by the prison camp system commander, General Friedrich-which entitled

Hoffman to visit all POW camps and hospitals in Prussia; converse freely and unhampered with Allied prisoners,

without a German interpreter or official;

When Conrad Hoffman entered the field in September 1915, he was the pioneer of WPA work in Germany. He

received a Ministry of War permit-signed by the prison camp system commander, General Friedrich-which entitled

Hoffman to visit all POW camps and hospitals in Prussia; converse freely and unhampered with Allied prisoners,

without a German interpreter or official;

and to take notes and photographs of the POWs and camp equipment. The American secretary could also exchange

food and clothing for the benefit of Allied prisoners, as well as carry mail. This permit gave Hoffman unusual

freedom of action in the prison camps, but it did not eliminate all bureaucratic obstacles. Camp commandants

could deny Hoffman access to prison camps unless he received a permit from the Army Corps Command staff (there

were nineteen corps headquarters in Prussia).

and to take notes and photographs of the POWs and camp equipment. The American secretary could also exchange

food and clothing for the benefit of Allied prisoners, as well as carry mail. This permit gave Hoffman unusual

freedom of action in the prison camps, but it did not eliminate all bureaucratic obstacles. Camp commandants

could deny Hoffman access to prison camps unless he received a permit from the Army Corps Command staff (there

were nineteen corps headquarters in Prussia).

The Berlin permit also did not allow Hoffman access to prison camps in Bavaria, Saxony, or Württemberg.

To visit these facilities, Hoffman needed special permits from the Ministries of War from each kingdom, plus

Army Corps Commands, if required. In practice, Hoffman needed a Ministry of War permit, an Army Corps Command permit, and an

Inspector of the Army Corps letter of reference; he also had to notify the camp commandant of his intention

to visit before arriving at each prison camp. Shortly after his arrival in Germany, Hoffman was joined by

another member of the Flying Squadron, James E. Sprunger. A Swedish YMCA secretary, Reverend H. Neander,

arrived in Germany on 1 October 1915. He was paid by the International Committee and served with the American

WPA secretaries until his departure on 1 January 1916. These secretaries were the nucleus of the Red Triangle's

WPA program in Germany.26

The Berlin permit also did not allow Hoffman access to prison camps in Bavaria, Saxony, or Württemberg.

To visit these facilities, Hoffman needed special permits from the Ministries of War from each kingdom, plus

Army Corps Commands, if required. In practice, Hoffman needed a Ministry of War permit, an Army Corps Command permit, and an

Inspector of the Army Corps letter of reference; he also had to notify the camp commandant of his intention

to visit before arriving at each prison camp. Shortly after his arrival in Germany, Hoffman was joined by

another member of the Flying Squadron, James E. Sprunger. A Swedish YMCA secretary, Reverend H. Neander,

arrived in Germany on 1 October 1915. He was paid by the International Committee and served with the American

WPA secretaries until his departure on 1 January 1916. These secretaries were the nucleus of the Red Triangle's

WPA program in Germany.26

25

The liberal terms of the Ministry of War permit combined with the bureaucratic hurdles imposed on Hoffman

resulted in other problems as well. To Germans engaged in a total war, any neutral citizen was a target of

suspicion. But for the Allied POWs, a neutral official carrying imperial papers was a possible German agent,

sent to spy and report on their activities

The liberal terms of the Ministry of War permit combined with the bureaucratic hurdles imposed on Hoffman

resulted in other problems as well. To Germans engaged in a total war, any neutral citizen was a target of

suspicion. But for the Allied POWs, a neutral official carrying imperial papers was a possible German agent,

sent to spy and report on their activities

and complaints. Breaking the ice with Allied POWs was Hoffman's first important challenge, and it was

an initial obstacle in terms of gaining the trust of the prisoners. Association WPA work was a unique

social welfare operation. Most relief agencies worked from the outside, sending in supplies and equipment

but not developing personal relationships with the prisoners, apart from the camp relief committees. The

YMCA always emphasized the personal element as the most important

and complaints. Breaking the ice with Allied POWs was Hoffman's first important challenge, and it was

an initial obstacle in terms of gaining the trust of the prisoners. Association WPA work was a unique

social welfare operation. Most relief agencies worked from the outside, sending in supplies and equipment

but not developing personal relationships with the prisoners, apart from the camp relief committees. The

YMCA always emphasized the personal element as the most important

factor in establishing relief programs in prison camps. The Red Triangle worker's slogan was "Helping men

to help themselves." Each secretary also had to overcome sectarian prejudices among the POWs. The YMCA was

a Protestant organization-Catholic and Orthodox prisoners were suspicious of the agency's objectives. Under

the agreement with the German government, secretaries could not conduct propaganda work, although they could

organize interdenominational meetings. It was important for American secretaries to emphasize that Red Triangle

service was for all war prisoners, irrespective of nationality or religious creed. They needed unusual

diplomatic skills to win and keep the confidence of German officers and guards as well as the POWs, but this was

an essential prerequisite for successful WPA work.27

factor in establishing relief programs in prison camps. The Red Triangle worker's slogan was "Helping men

to help themselves." Each secretary also had to overcome sectarian prejudices among the POWs. The YMCA was

a Protestant organization-Catholic and Orthodox prisoners were suspicious of the agency's objectives. Under

the agreement with the German government, secretaries could not conduct propaganda work, although they could

organize interdenominational meetings. It was important for American secretaries to emphasize that Red Triangle

service was for all war prisoners, irrespective of nationality or religious creed. They needed unusual

diplomatic skills to win and keep the confidence of German officers and guards as well as the POWs, but this was

an essential prerequisite for successful WPA work.27

26

Armed with their Ministry of War permits, Hoffman and Sprunger toured German prison camps extensively

in western Germany, starting on 2 October 1915. They first visited the military hospital at Halle-am-Saale in Prussian Saxony. They then proceeded to Carlsruhe, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Baden.

Hoffman and Sprunger had a friendly and informal meeting with the heir to the duchy and future Chancellor

of the German Empire, Prince Max. Harte advised Hoffman to ask the prince to serve as the patron of the

YMCA's WPA work in Germany.

The prince was deeply interested in POW relief work, and was already intensely involved in providing welfare programs for prisoners of war.

Armed with their Ministry of War permits, Hoffman and Sprunger toured German prison camps extensively

in western Germany, starting on 2 October 1915. They first visited the military hospital at Halle-am-Saale in Prussian Saxony. They then proceeded to Carlsruhe, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Baden.

Hoffman and Sprunger had a friendly and informal meeting with the heir to the duchy and future Chancellor

of the German Empire, Prince Max. Harte advised Hoffman to ask the prince to serve as the patron of the

YMCA's WPA work in Germany.

The prince was deeply interested in POW relief work, and was already intensely involved in providing welfare programs for prisoners of war.

Prince Max graciously agreed to lead the

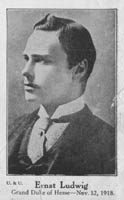

committee. The Americans' next stop was Darmstadt, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt. They

enjoyed an informal meeting with Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig. The grand duke, who spoke English and whose

mother was a British princess, showed deep interest in YMCA work and arranged for his adjutant to take them

on a tour of Hessian prison camps. The next day, the American secretaries toured several hospitals and camps

near Darmstadt.

They inspected a military hospital for French and Russian prisoners, a quarantine compound,

delousing buildings, and prison compounds featuring kitchens, canteens, reading rooms, playgrounds, a

theater, workshops (shoemaker, tailor, carpentry, and art studios), a church barrack, vegetable and flower

gardens, and drainage and sewage systems. Hoffman determined that the Germans had nothing to hide, and was

impressed with German efficiency and organization. He praised German Kultur, and the commandants'

benevolence to Allied POWs. A degree of rivalry between camp commanders also improved the lot of

prisoners.28

Prince Max graciously agreed to lead the

committee. The Americans' next stop was Darmstadt, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt. They

enjoyed an informal meeting with Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig. The grand duke, who spoke English and whose

mother was a British princess, showed deep interest in YMCA work and arranged for his adjutant to take them

on a tour of Hessian prison camps. The next day, the American secretaries toured several hospitals and camps

near Darmstadt.

They inspected a military hospital for French and Russian prisoners, a quarantine compound,

delousing buildings, and prison compounds featuring kitchens, canteens, reading rooms, playgrounds, a

theater, workshops (shoemaker, tailor, carpentry, and art studios), a church barrack, vegetable and flower

gardens, and drainage and sewage systems. Hoffman determined that the Germans had nothing to hide, and was

impressed with German efficiency and organization. He praised German Kultur, and the commandants'

benevolence to Allied POWs. A degree of rivalry between camp commanders also improved the lot of

prisoners.28

27

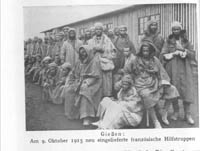

Hoffman and Sprunger then traveled to visit the prison camps at Giessen and Wetzlar. At Giessen, Hoffman

took pity on the colonial prisoners. He was moved by a Senegalese prisoner, stranded in a strange country

and far from home, and by an Indian soldier who spoke and understood only a native dialect. They then

continued to the POW camp at Limburg-am-Lahn, which held ten thousand men. Over half of the prisoners were sent

out of the camp to work in the local fields. Hoffman and Sprunger visited the censor office, which was

inspecting parcels, and the parcel delivery service, which forwarded packages to transferred prisoners.

Hoffman and Sprunger then traveled to visit the prison camps at Giessen and Wetzlar. At Giessen, Hoffman

took pity on the colonial prisoners. He was moved by a Senegalese prisoner, stranded in a strange country

and far from home, and by an Indian soldier who spoke and understood only a native dialect. They then

continued to the POW camp at Limburg-am-Lahn, which held ten thousand men. Over half of the prisoners were sent

out of the camp to work in the local fields. Hoffman and Sprunger visited the censor office, which was

inspecting parcels, and the parcel delivery service, which forwarded packages to transferred prisoners.

At the Russian POW camp in Worms, the prisoners had a special barrack for religious services and an

excellent hospital. The German officials at this camp strongly encouraged the establishment of Association

work, and Sprunger believed that this presented an opportunity to set up an educational program. Hoffman

took special interest in a talented Russian woodcarver. The YMCA provided the camp with a workshop, and

Hoffman took him to a lumberyard to purchase wood. The POW constructed violins and mandolins, providing

instruments for the camp orchestra and selling the remainder to other prison camps. Most importantly, he

trained apprentices, giving them a chance to develop a new trade. As Hoffman pointed out, "The inspiration

and encouragement thus given him by a comparatively small outlay of money on our part would have been

difficult to estimate."29 The American secretary

described a trickle-down social effect, whereby a small amount of money could have an important impact on

the future lives of POWs.30

At the Russian POW camp in Worms, the prisoners had a special barrack for religious services and an

excellent hospital. The German officials at this camp strongly encouraged the establishment of Association

work, and Sprunger believed that this presented an opportunity to set up an educational program. Hoffman

took special interest in a talented Russian woodcarver. The YMCA provided the camp with a workshop, and

Hoffman took him to a lumberyard to purchase wood. The POW constructed violins and mandolins, providing

instruments for the camp orchestra and selling the remainder to other prison camps. Most importantly, he

trained apprentices, giving them a chance to develop a new trade. As Hoffman pointed out, "The inspiration

and encouragement thus given him by a comparatively small outlay of money on our part would have been

difficult to estimate."29 The American secretary

described a trickle-down social effect, whereby a small amount of money could have an important impact on

the future lives of POWs.30

28

The American secretaries finished their tour at Ruhleben. They found the Association making good headway

among the British internees. The POWs had established a central committee representing all of the denominations in the camp, as well as

members from various camp committees (education, government, entertainment, and other organizations). The

participants approved a temporary constitution, and

The American secretaries finished their tour at Ruhleben. They found the Association making good headway

among the British internees. The POWs had established a central committee representing all of the denominations in the camp, as well as

members from various camp committees (education, government, entertainment, and other organizations). The

participants approved a temporary constitution, and

the groundbreaking for a YMCA hut was scheduled for the following week. The school at Ruhleben had grown

to 1,800 students and 150 teachers. Hoffman considered the ten thousand-man prisoner camp a wonderful opportunity

for Association work. After this tour, Hoffman decided to assign Sprunger to work in the XVIII Army Corps

district in camps under the command of the general staff at Frankfurt-am-Main.31

the groundbreaking for a YMCA hut was scheduled for the following week. The school at Ruhleben had grown

to 1,800 students and 150 teachers. Hoffman considered the ten thousand-man prisoner camp a wonderful opportunity

for Association work. After this tour, Hoffman decided to assign Sprunger to work in the XVIII Army Corps

district in camps under the command of the general staff at Frankfurt-am-Main.31

29

In addition to Hoffman and Sprunger, other American YMCA secretaries toured German prison camps during the

fall of 1915. Marshall M. Bartholomew visited the prison camp at Göttingen and was impressed by how quickly the

Association hut had become the center of social life. He reported that the library was constantly used,

and classes were well attended.

In addition to Hoffman and Sprunger, other American YMCA secretaries toured German prison camps during the

fall of 1915. Marshall M. Bartholomew visited the prison camp at Göttingen and was impressed by how quickly the

Association hut had become the center of social life. He reported that the library was constantly used,

and classes were well attended.

Prisoners enjoyed the music of a talented orchestra. Bartholomew also visited the publishing office, where

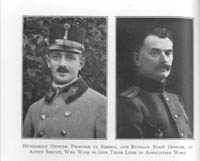

the camp newspaper was composed and printed. Bartholomew then toured the Allied officers' POW camp at

Hannoverisch-Münden, where the Germans had converted a large manufacturing building into the officers'

quarters. The POWs had a garden, tennis court, and an Association hall, constructed by the American YMCA.

After his visit, Bartholomew became a WPA Secretary working on behalf of Central Power POWs in Russia. His

observations of WPA work in Germany gave him the background necessary to establish similar welfare programs

in the spirit of reciprocity.32

Prisoners enjoyed the music of a talented orchestra. Bartholomew also visited the publishing office, where

the camp newspaper was composed and printed. Bartholomew then toured the Allied officers' POW camp at

Hannoverisch-Münden, where the Germans had converted a large manufacturing building into the officers'

quarters. The POWs had a garden, tennis court, and an Association hall, constructed by the American YMCA.

After his visit, Bartholomew became a WPA Secretary working on behalf of Central Power POWs in Russia. His

observations of WPA work in Germany gave him the background necessary to establish similar welfare programs

in the spirit of reciprocity.32

30

Other neutral countries also sent national YMCA secretaries to Germany relatively early in the war. Hermann

C. Rutgers, General Secretary of the Dutch Student Christian Movement, received permission from the Ministry

of War to visit Friedrichsfeld, a Prussian camp, in December 1915. Dutch Association members were sending parcels

to French prisoners at the camp and asked Rutgers to inspect conditions there. Rutgers was accompanied by Pastor

Charles Correvon, the minister

Other neutral countries also sent national YMCA secretaries to Germany relatively early in the war. Hermann

C. Rutgers, General Secretary of the Dutch Student Christian Movement, received permission from the Ministry

of War to visit Friedrichsfeld, a Prussian camp, in December 1915. Dutch Association members were sending parcels

to French prisoners at the camp and asked Rutgers to inspect conditions there. Rutgers was accompanied by Pastor

Charles Correvon, the minister

of the French Church in Frankfurt-am-Main. Correvon was born in Switzerland, but had become a naturalized German

subject, and held a general permit to visit all prison camps that contained French Protestants. The prison camp at

Friedrichsfeld held a total of thirty-five thousand prisoners (twenty thousand French POWs, twelve thousand Russians, and six hundred British prisoners).

Rutgers and Correvon

of the French Church in Frankfurt-am-Main. Correvon was born in Switzerland, but had become a naturalized German

subject, and held a general permit to visit all prison camps that contained French Protestants. The prison camp at

Friedrichsfeld held a total of thirty-five thousand prisoners (twenty thousand French POWs, twelve thousand Russians, and six hundred British prisoners).

Rutgers and Correvon

inspected the barracks, bathing facilities, barber shops, disinfecting plant, isolation camp, hospital, store

houses, post office, bank, school, and church. The latter was an empty barrack where the POWs could participate

in religious services. Seven Roman Catholic priests and one Protestant minister served the prison population.

The prisoners set up a philanthropic committee to supervise camp relief operations; the committee consisted of

one hundred men, representing all of the nationalities in the camp. They identified needy prisoners and

distributed relief parcels sent to the camp. Physical exercise was promoted, and boxing became especially

popular among the POWs.33

inspected the barracks, bathing facilities, barber shops, disinfecting plant, isolation camp, hospital, store

houses, post office, bank, school, and church. The latter was an empty barrack where the POWs could participate

in religious services. Seven Roman Catholic priests and one Protestant minister served the prison population.

The prisoners set up a philanthropic committee to supervise camp relief operations; the committee consisted of

one hundred men, representing all of the nationalities in the camp. They identified needy prisoners and

distributed relief parcels sent to the camp. Physical exercise was promoted, and boxing became especially

popular among the POWs.33

31

The school at Friedrichsfeld was quite developed. Classes ranged from basic reading for illiterates to foreign

languages (especially Flemish), drawing, painting, and stenography. Prisoners could also learn new skills,

including furniture- and doll-making, wood-carving, and postcard design. Most importantly, the Germans established

a rehabilitation center for wounded and disabled prisoners. Many of these men would not be able to return to their

pre-war trades, so they learned new trades such as tailoring, barbering, watch-making, bookkeeping, bookbinding,

printing, shoemaking, and cabinet-making. The rehabilitation center had twenty-one instructors, all POWs. The

commandant spent nine thousand Marks of camp funds to set up and equip this school. The idea of a rehabilitation center

was readily adopted by the American YMCA as an important component of the POW relief program. Rutgers freely

talked to the prisoners, and found that they had no complaints.

The school at Friedrichsfeld was quite developed. Classes ranged from basic reading for illiterates to foreign

languages (especially Flemish), drawing, painting, and stenography. Prisoners could also learn new skills,

including furniture- and doll-making, wood-carving, and postcard design. Most importantly, the Germans established

a rehabilitation center for wounded and disabled prisoners. Many of these men would not be able to return to their