Table of Contents

Chapter 4

"For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms": American YMCA Prisoner-of-War Diplomacy in Western Europe

1

The International Committee of the North American YMCA sent its first two "ambassadors-at-large" to Europe in January

1915. After the International Committee embraced the goal of assisting POWs, the next step was negotiating with

belligerent governments to gain access to war prisoners.

The International Committee of the North American YMCA sent its first two "ambassadors-at-large" to Europe in January

1915. After the International Committee embraced the goal of assisting POWs, the next step was negotiating with

belligerent governments to gain access to war prisoners.

John R. Mott wrote to Paul Des Gouttes, President of the World's Alliance, on 12 January 1915, to inform the

Executive Committee that Archibald Clinton Harte would negotiate with the German government. He also wrote letters

to Christian Phildius and Emmanuel Sautter in Geneva introducing Harte and Carlisle V. Hibbard. Both Americans were

experienced in providing services to troops in battle and working overseas.

John R. Mott wrote to Paul Des Gouttes, President of the World's Alliance, on 12 January 1915, to inform the

Executive Committee that Archibald Clinton Harte would negotiate with the German government. He also wrote letters

to Christian Phildius and Emmanuel Sautter in Geneva introducing Harte and Carlisle V. Hibbard. Both Americans were

experienced in providing services to troops in battle and working overseas.

Harte was a chaplain with the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War, and gained extensive Association experience as General Secretary of the Indian National YMCA Council (1907-1914).

Hibbard served as the Associate National Secretary for Japan from 1902 to 1914, and

provided welfare assistance to Japanese troops in Korea and Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War.

Their goal was to persuade belligerent governments to allow American secretaries access to POW camps and to establish and develop

the Association program directed at improving the welfare of the captives.1

Harte was a chaplain with the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War, and gained extensive Association experience as General Secretary of the Indian National YMCA Council (1907-1914).

Hibbard served as the Associate National Secretary for Japan from 1902 to 1914, and

provided welfare assistance to Japanese troops in Korea and Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War.

Their goal was to persuade belligerent governments to allow American secretaries access to POW camps and to establish and develop

the Association program directed at improving the welfare of the captives.1

Negotiations Begin in Britain

2

The pair arrived in England and immediately began negotiations with British officials. By the beginning of 1915,

the English YMCA had expanded the scope of its services for the British armed forces. By the end of January, the

English National Council had collected over £ 225,000 for war service operations, and the Red Triangle ranks included

five hundred salaried secretaries and two thousand volunteers.

The pair arrived in England and immediately began negotiations with British officials. By the beginning of 1915,

the English YMCA had expanded the scope of its services for the British armed forces. By the end of January, the

English National Council had collected over £ 225,000 for war service operations, and the Red Triangle ranks included

five hundred salaried secretaries and two thousand volunteers.

The English Association had sixty secretaries in France, seven in Egypt, and ten special secretaries in India.

Harte and Hibbard were deeply impressed by the generous treatment German prisoners received. The two Americans visited

prison camps across the British Isles, and reported that conditions and treatment were uniformly good.2

The English Association had sixty secretaries in France, seven in Egypt, and ten special secretaries in India.

Harte and Hibbard were deeply impressed by the generous treatment German prisoners received. The two Americans visited

prison camps across the British Isles, and reported that conditions and treatment were uniformly good.2

3 At this point in the war, the English National Council had not established a regular POW program for German prisoners. Instead, the English YMCA sent its regular prison secretary, F. L. Porter, to visit POW camps where he could gain admission. Porter met with the POWs, offered them small personal services, and distributed reading material. In addition, Porter provided Association services to British guards to maintain their morale.3

4 The two American secretaries soon encountered their first diplomatic obstacle. Although the War Office opened English prison camps to Harte and Hibbard for inspection, British officials would not agree on a welfare program for German prisoners on a national basis. English military authorities did not believe that extending general permits to a neutral welfare agency to organize social activities for prisoners was necessary. Instead, the War Office left the decision to admit American secretaries and establish Association services for POWs to individual camp commandants. The English National Council accepted this restriction and suggested that Harte and Hibbard develop Red Triangle services in prison camps gradually, on an ad hoc basis, to build up good will with individual prison commanders. Over time, the YMCA secretaries could demonstrate the value of a YMCA POW program to the War Office.4

5

But Harte and Hibbard recognized that, in order to gain access to German prison camps, they would have to face

authorities in Berlin who would demand equal treatment for their troops imprisoned in England. When Hibbard first

inspected British prison camps, he was accompanied by Dr. Herman Rutgers, General Secretary of the Dutch Student

Christian Movement (SCM). Rutgers was one of two neutral nationals accredited by the Prisoners' Help Committee in

Germany, and had been commissioned to visit German students incarcerated in England. Rutgers' mission was to collect

information for German authorities about British war prison conditions. By gaining concessions from one government

to permit American YMCA secretaries to visit prison camps, the International Committee representatives hoped to use

diplomatic leverage to gain similar concessions from other belligerent governments for equal, or better, privileges.

This "Principle of Reciprocity" became the basis of Harte and Hibbard's negotiations, and was the key to Association

access to military prison camps. The British government then offered a compromise. Both the War Office and the Foreign

Office were sympathetic to the goals of the American YMCA, and were ready to cooperate if the Wilson Administration

extended official support to the two secretaries. If the American embassy issued a formal request, then the Foreign

Office would grant permission to establish an Association program. Harte and Hibbard conferred with the English

National Council. They agreed that POW service would be far more efficient if the YMCA received official permission

from the War Office and the Foreign Office. American secretaries could then initiate and expand social work for POWs

in cooperation with the English National Council.5

But Harte and Hibbard recognized that, in order to gain access to German prison camps, they would have to face

authorities in Berlin who would demand equal treatment for their troops imprisoned in England. When Hibbard first

inspected British prison camps, he was accompanied by Dr. Herman Rutgers, General Secretary of the Dutch Student

Christian Movement (SCM). Rutgers was one of two neutral nationals accredited by the Prisoners' Help Committee in

Germany, and had been commissioned to visit German students incarcerated in England. Rutgers' mission was to collect

information for German authorities about British war prison conditions. By gaining concessions from one government

to permit American YMCA secretaries to visit prison camps, the International Committee representatives hoped to use

diplomatic leverage to gain similar concessions from other belligerent governments for equal, or better, privileges.

This "Principle of Reciprocity" became the basis of Harte and Hibbard's negotiations, and was the key to Association

access to military prison camps. The British government then offered a compromise. Both the War Office and the Foreign

Office were sympathetic to the goals of the American YMCA, and were ready to cooperate if the Wilson Administration

extended official support to the two secretaries. If the American embassy issued a formal request, then the Foreign

Office would grant permission to establish an Association program. Harte and Hibbard conferred with the English

National Council. They agreed that POW service would be far more efficient if the YMCA received official permission

from the War Office and the Foreign Office. American secretaries could then initiate and expand social work for POWs

in cooperation with the English National Council.5

6

Despite this open door, the Americans were again frustrated as Ambassador Walter Hines Page refused to assume authority

for the American YMCA POW program. Page's position was surprising for several reasons. First, the embassy lacked the

staff, resources, and experience to implement an effective POW program for German prisoners in England, as reflected

in Anderson's memo of December 1914.

Despite this open door, the Americans were again frustrated as Ambassador Walter Hines Page refused to assume authority

for the American YMCA POW program. Page's position was surprising for several reasons. First, the embassy lacked the

staff, resources, and experience to implement an effective POW program for German prisoners in England, as reflected

in Anderson's memo of December 1914.

As a result, the American government would have to rely on the assistance of U.S. welfare organizations to undertake

this social work. Second, Mott and the American YMCA clearly had the full support of President Woodrow Wilson,

attested to in the papers the General Secretary carried to England in October 1914. Harte and Hibbard cabled the

International Committee in New York to gain the support of the Department of State. The General Secretary immediately

proceeded to Washington and met with State Department officials. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan finally

extended government recognition of the American YMCA's POW work on 27 February 1915.6

As a result, the American government would have to rely on the assistance of U.S. welfare organizations to undertake

this social work. Second, Mott and the American YMCA clearly had the full support of President Woodrow Wilson,

attested to in the papers the General Secretary carried to England in October 1914. Harte and Hibbard cabled the

International Committee in New York to gain the support of the Department of State. The General Secretary immediately

proceeded to Washington and met with State Department officials. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan finally

extended government recognition of the American YMCA's POW work on 27 February 1915.6

7 While the American secretaries waited for U.S. government sanction to gain access to British prison camps, Hibbard and Harte decided to separate and proceed on their mission in other European capitals. On 10 February 1915, Hibbard left for Paris and Harte traveled to Berlin. They recognized that negotiations with belligerent governments would be long and grueling, and agreed that they could speed up access to the prison camps by starting negotiations independently.7

Hibbard and French Negotiations

8

While the International Committee formulated a POW relief plan in Europe, the French YMCA made the first efforts

to begin work for German prisoners. The French army assigned J. W. Namblard, a French Association secretary, as

chaplain to the military and naval sanitary formations at Rochefort. He began work in November 1914, serving German

wounded as part of his duties. He soon began Association work for German prisoners at Rochefort-sur-Mer, both at the

depot and in the military hospital. He visited wounded and sick POWs, distributing Bibles and other books. The

chaplain was upset when he found that Germans who succumbed to their wounds or disease were buried without a religious

service. He protested, and French military authorities agreed to provide clergy for future burials. Namblard had a

limited command of German, but he nevertheless planned extensive Christmas services for the German prisoners in

December 1914. With the assistance of Pastor Terrisse, a Swiss minister, he arranged to have Christmas services and

carol singing for the POWs at Rochefort and on the island of Aix. For German prisoners in the hospital, Namblard

visited the bed-ridden and distributed oranges and games to the patients. He also arranged to have a candle lit at

the head of each bed on Christmas Eve and Christmas carols sung in each ward. At a nearby internment camp, which

housed eight hundred German and Austro-Hungarian civilians, Namblard met with some of the captives. He sought to gain access

to the prisoners, but had to work through the Ministry of the Interior, which administered the camp. By March 1915,

Namblard was working in ten prison camps in the vicinity around La Rochelle, and he had to travel approximately forty

kilometers to visit all of the facilities. He also gained access to Central Power civilians assigned to internment

facilities. For Easter 1915, Namblard arranged special religious services, and distributed German tracts and New

Testaments to thousands of prisoners. The French secretary was one of the Association's pioneers in POW relief in

France.8

While the International Committee formulated a POW relief plan in Europe, the French YMCA made the first efforts

to begin work for German prisoners. The French army assigned J. W. Namblard, a French Association secretary, as

chaplain to the military and naval sanitary formations at Rochefort. He began work in November 1914, serving German

wounded as part of his duties. He soon began Association work for German prisoners at Rochefort-sur-Mer, both at the

depot and in the military hospital. He visited wounded and sick POWs, distributing Bibles and other books. The

chaplain was upset when he found that Germans who succumbed to their wounds or disease were buried without a religious

service. He protested, and French military authorities agreed to provide clergy for future burials. Namblard had a

limited command of German, but he nevertheless planned extensive Christmas services for the German prisoners in

December 1914. With the assistance of Pastor Terrisse, a Swiss minister, he arranged to have Christmas services and

carol singing for the POWs at Rochefort and on the island of Aix. For German prisoners in the hospital, Namblard

visited the bed-ridden and distributed oranges and games to the patients. He also arranged to have a candle lit at

the head of each bed on Christmas Eve and Christmas carols sung in each ward. At a nearby internment camp, which

housed eight hundred German and Austro-Hungarian civilians, Namblard met with some of the captives. He sought to gain access

to the prisoners, but had to work through the Ministry of the Interior, which administered the camp. By March 1915,

Namblard was working in ten prison camps in the vicinity around La Rochelle, and he had to travel approximately forty

kilometers to visit all of the facilities. He also gained access to Central Power civilians assigned to internment

facilities. For Easter 1915, Namblard arranged special religious services, and distributed German tracts and New

Testaments to thousands of prisoners. The French secretary was one of the Association's pioneers in POW relief in

France.8

9

In the meantime, Hibbard arrived in France as the American YMCA's "ambassador-at-large." With the support of

Ambassador William Graves Sharp, Hibbard began negotiations with Alexander Millerand, the French Minister of

War. During initial talks, Hibbard found the French as reluctant to accept American YMCA assistance as the British

had been. At every turn, Hibbard ran into bureaucratic obstacles. Negotiations regarding military prisoners required

an agreement with the Ministry of War, while a separate set of talks with the Ministry of the Interior was necessary

to begin work with civilian internees. Sautter warned Hibbard that he did not believe that the French government

was ready to accept any foreign assistance. The one factor working in Hibbard's favor was the scarcity of French

resources available for POW relief. A few French chaplains, including Namblard, had undertaken social work on a

limited scale for POWs, but the army mobilization had emaciated the ranks of domestic social service organizations.

The manpower drain left no effective welfare agencies to meet the needs of war prisoners or soldiers in France. As

a result, the French government was willing to consider foreign offers of welfare assistance.

In the meantime, Hibbard arrived in France as the American YMCA's "ambassador-at-large." With the support of

Ambassador William Graves Sharp, Hibbard began negotiations with Alexander Millerand, the French Minister of

War. During initial talks, Hibbard found the French as reluctant to accept American YMCA assistance as the British

had been. At every turn, Hibbard ran into bureaucratic obstacles. Negotiations regarding military prisoners required

an agreement with the Ministry of War, while a separate set of talks with the Ministry of the Interior was necessary

to begin work with civilian internees. Sautter warned Hibbard that he did not believe that the French government

was ready to accept any foreign assistance. The one factor working in Hibbard's favor was the scarcity of French

resources available for POW relief. A few French chaplains, including Namblard, had undertaken social work on a

limited scale for POWs, but the army mobilization had emaciated the ranks of domestic social service organizations.

The manpower drain left no effective welfare agencies to meet the needs of war prisoners or soldiers in France. As

a result, the French government was willing to consider foreign offers of welfare assistance.

10

On February 23, Hibbard received conditional approval from the War Ministry to initiate limited work for prisoners.

Military officials were willing to allow American secretaries to accompany clergymen visiting prison camps to

distribute books and games and provide entertainment. The French also accepted a book exchange program through the

Stuttgart library for German prisoners. Hibbard immediately cabled the International Committee to request the

assignment of two American secretaries to begin Association POW work in France. Most importantly, the French government

promised to accept even greater American YMCA assistance if the Germans agreed to similar concessions. This understanding

marked the first application of the "Principle of Reciprocity," which became the foundation of YMCA diplomacy. One

country would accept Association social work for POWs under its control if comparable programs were established for

its imprisoned nationals.9

On February 23, Hibbard received conditional approval from the War Ministry to initiate limited work for prisoners.

Military officials were willing to allow American secretaries to accompany clergymen visiting prison camps to

distribute books and games and provide entertainment. The French also accepted a book exchange program through the

Stuttgart library for German prisoners. Hibbard immediately cabled the International Committee to request the

assignment of two American secretaries to begin Association POW work in France. Most importantly, the French government

promised to accept even greater American YMCA assistance if the Germans agreed to similar concessions. This understanding

marked the first application of the "Principle of Reciprocity," which became the foundation of YMCA diplomacy. One

country would accept Association social work for POWs under its control if comparable programs were established for

its imprisoned nationals.9

Harte Arrives in Germany

11

When Harte arrived in Berlin, he first met with Dr. Karl Axenfeld, Director of the Protestant Mission in Germany

and a close friend of Mott's. Axenfeld approached the Chaplain-General of the German Army regarding American YMCA

access to prison camps. Although the request was favorably received, Axenfeld did not believe that much progress

could be made at that time, because "the situation was extremely difficult and it might be necessary to remain

quiet for some time." Unperturbed, Harte cabled Phildius in Geneva for assistance. Phildius was a naturalized

Swiss citizen with important connections in Berlin (the World's Alliance General Secretary was an ideal candidate

for war prisoner diplomacy: he was German by birth and his wife was Scottish). He agreed to come to Berlin to

assist Harte in his quest. In the meantime, Harte met with Ambassador James W. Gerard, who became an enthusiastic

supporter of the American YMCA mission. Ambassador Gerard and the U.S. embassy staff inundated the Foreign Ministry

with requests to allow the American YMCA to enter POW camps to establish welfare operations for Allied prisoners.

From his work in prison camps in Germany, and through communications with U.S. embassy officials in Petrograd,

Gerard did all he could to improve the lot of Allied prisoners in Germany as well as for Central Power POWs in Russia.

The ambassador recognized that something had to be done for these men at once, and that the American YMCA was the

most effective tool for this purpose.10

When Harte arrived in Berlin, he first met with Dr. Karl Axenfeld, Director of the Protestant Mission in Germany

and a close friend of Mott's. Axenfeld approached the Chaplain-General of the German Army regarding American YMCA

access to prison camps. Although the request was favorably received, Axenfeld did not believe that much progress

could be made at that time, because "the situation was extremely difficult and it might be necessary to remain

quiet for some time." Unperturbed, Harte cabled Phildius in Geneva for assistance. Phildius was a naturalized

Swiss citizen with important connections in Berlin (the World's Alliance General Secretary was an ideal candidate

for war prisoner diplomacy: he was German by birth and his wife was Scottish). He agreed to come to Berlin to

assist Harte in his quest. In the meantime, Harte met with Ambassador James W. Gerard, who became an enthusiastic

supporter of the American YMCA mission. Ambassador Gerard and the U.S. embassy staff inundated the Foreign Ministry

with requests to allow the American YMCA to enter POW camps to establish welfare operations for Allied prisoners.

From his work in prison camps in Germany, and through communications with U.S. embassy officials in Petrograd,

Gerard did all he could to improve the lot of Allied prisoners in Germany as well as for Central Power POWs in Russia.

The ambassador recognized that something had to be done for these men at once, and that the American YMCA was the

most effective tool for this purpose.10

12

Harte also met with Dr. F. A. Speicker, president of the German Evangelical Missions' Aid. This organization,

formed in December 1914, also sought permission from the Ministry of War to provide spiritual assistance to POWs

in Germany. Reverend A. W. Schreiber, secretary of the German Evangelical Missions' Aid, readily agreed to meet

with Harte and Phildius and combine forces. Schreiber informed them that a member of the Foreign Office was

willing to promote their plan to aid war prisoners. He recommended that the German YMCA support the American

application as the best means to receive the necessary permission. The Ministry of War had extended official

recognition to the Protestant Committee for its proposed work, and Schreiber encouraged Harte to apply for similar

privileges through this organization. Schreiber arranged for Harte and Phildius to meet with representatives of

the Foreign Office. In addition, the German Red Cross agreed to cooperate with YMCA officials and intervened on

their behalf through their contacts in the Ministry of War. Dr. von Studt, Chairman of the POW Committee of the

German Red Cross, welcomed American YMCA assistance. He assigned Dr. Spencer, a German Red Cross official, to

introduce Harte and Phildius to the staff members of the War Ministry on 23 February 1915. Harte presented a plan

for relief work for Allied POWs in Germany to an attentive audience. The American secretary even enlisted the

support of the wife of the Chamberlain, whom he had met at the Protestant Mission. She called on the sister of

the Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, to solicit her support on behalf of the American YMCA, and arranged

for Harte to present his proposal to the Chancellor's staff.11

Harte also met with Dr. F. A. Speicker, president of the German Evangelical Missions' Aid. This organization,

formed in December 1914, also sought permission from the Ministry of War to provide spiritual assistance to POWs

in Germany. Reverend A. W. Schreiber, secretary of the German Evangelical Missions' Aid, readily agreed to meet

with Harte and Phildius and combine forces. Schreiber informed them that a member of the Foreign Office was

willing to promote their plan to aid war prisoners. He recommended that the German YMCA support the American

application as the best means to receive the necessary permission. The Ministry of War had extended official

recognition to the Protestant Committee for its proposed work, and Schreiber encouraged Harte to apply for similar

privileges through this organization. Schreiber arranged for Harte and Phildius to meet with representatives of

the Foreign Office. In addition, the German Red Cross agreed to cooperate with YMCA officials and intervened on

their behalf through their contacts in the Ministry of War. Dr. von Studt, Chairman of the POW Committee of the

German Red Cross, welcomed American YMCA assistance. He assigned Dr. Spencer, a German Red Cross official, to

introduce Harte and Phildius to the staff members of the War Ministry on 23 February 1915. Harte presented a plan

for relief work for Allied POWs in Germany to an attentive audience. The American secretary even enlisted the

support of the wife of the Chamberlain, whom he had met at the Protestant Mission. She called on the sister of

the Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, to solicit her support on behalf of the American YMCA, and arranged

for Harte to present his proposal to the Chancellor's staff.11

13

On the same day, Hibbard informed Harte that he had achieved some success in persuading the French Ministry of

War to consider allowing American YMCA secretaries to provide Association services to German prisoners if they

could be assured that German authorities would make similar concessions for French POWs in Germany. In addition,

the Department of State cabled the Foreign Ministry in support of Harte's proposal, placing additional official

weight behind his plan. Most importantly, the German public had serious concerns regarding the treatment of their

POWs in Russia, and Ministry of War officials viewed the American YMCA as a potential vehicle to help improve the

lot of German prisoners. Bombarded with requests from the German YMCA, relief organizations, Gerard and the State

Department, as well as Harte and Phildius, and coupled with the provisional concession from the French government,

the German Ministry of War decided to approve Harte's proposal. On March 6, Schreiber received a note from the War

Ministry indicating that "the War Ministry begs to inform you that it can only welcome the offer of the most

commendable cooperation of the Young Men's Christian Associations, and that it will render them every assistance

in reaching their aim speedily."12 The response of the

German government was far more generous than the tentative receptions of French or British officials. This was the

first concrete result of the Association's POW diplomacy, and a critical first step in gaining access to war prisoners.

Now the question was where the American YMCA should begin POW relief operations.13

On the same day, Hibbard informed Harte that he had achieved some success in persuading the French Ministry of

War to consider allowing American YMCA secretaries to provide Association services to German prisoners if they

could be assured that German authorities would make similar concessions for French POWs in Germany. In addition,

the Department of State cabled the Foreign Ministry in support of Harte's proposal, placing additional official

weight behind his plan. Most importantly, the German public had serious concerns regarding the treatment of their

POWs in Russia, and Ministry of War officials viewed the American YMCA as a potential vehicle to help improve the

lot of German prisoners. Bombarded with requests from the German YMCA, relief organizations, Gerard and the State

Department, as well as Harte and Phildius, and coupled with the provisional concession from the French government,

the German Ministry of War decided to approve Harte's proposal. On March 6, Schreiber received a note from the War

Ministry indicating that "the War Ministry begs to inform you that it can only welcome the offer of the most

commendable cooperation of the Young Men's Christian Associations, and that it will render them every assistance

in reaching their aim speedily."12 The response of the

German government was far more generous than the tentative receptions of French or British officials. This was the

first concrete result of the Association's POW diplomacy, and a critical first step in gaining access to war prisoners.

Now the question was where the American YMCA should begin POW relief operations.13

14

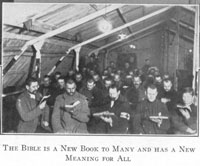

Preliminary relief work for Allied POWs had begun by early 1915. French-speaking German clergymen gained

permission to visit prison camps. These ministers described the deep spiritual needs in the camps. One pastor

had two thousand men attend an open-air service, even though there were only two hundred Protestant prisoners in the camp.

The ministers rapidly ran out of pamphlets and Gospels, and they believed that a true religious revival could

be fostered in prison camps. In the Berlin area, a large number of French priests were incarcerated as war

prisoners. They reported that the war had stirred up deep religious needs among the "neglected sons of the

French republic" and called for assistance. A French pastor who ministered to a congregation in Berlin visited

a prison camp twice weekly. Harte admired his industry as he distributed four thousand French Gospels, trousers, warm

shirts, apples, chocolate, and tobacco. The funds for this charity were provided by personal friends and French

congregations in Berlin and Basel. He also organized an Association (and a choir) in this prison, and knew of

Associations for French POWs in two other prison camps. The American YMCA could take advantage of many clergy

that were willing to distribute books and comforts to war prisoners. In addition, Association secretaries from

neutral countries tried to provide assistance to Allied prisoners in Germany. A Swiss Student Secretary traveled

to Germany in February 1915 and was received by Grand Duchess Luise of Baden. They visited a lazaret in Carlsruhe,

where the German Red Cross was caring for German wounded.14

Preliminary relief work for Allied POWs had begun by early 1915. French-speaking German clergymen gained

permission to visit prison camps. These ministers described the deep spiritual needs in the camps. One pastor

had two thousand men attend an open-air service, even though there were only two hundred Protestant prisoners in the camp.

The ministers rapidly ran out of pamphlets and Gospels, and they believed that a true religious revival could

be fostered in prison camps. In the Berlin area, a large number of French priests were incarcerated as war

prisoners. They reported that the war had stirred up deep religious needs among the "neglected sons of the

French republic" and called for assistance. A French pastor who ministered to a congregation in Berlin visited

a prison camp twice weekly. Harte admired his industry as he distributed four thousand French Gospels, trousers, warm

shirts, apples, chocolate, and tobacco. The funds for this charity were provided by personal friends and French

congregations in Berlin and Basel. He also organized an Association (and a choir) in this prison, and knew of

Associations for French POWs in two other prison camps. The American YMCA could take advantage of many clergy

that were willing to distribute books and comforts to war prisoners. In addition, Association secretaries from

neutral countries tried to provide assistance to Allied prisoners in Germany. A Swiss Student Secretary traveled

to Germany in February 1915 and was received by Grand Duchess Luise of Baden. They visited a lazaret in Carlsruhe,

where the German Red Cross was caring for German wounded.14

15

Before Harte received permission from the Ministry of War to begin Association work in prison facilities, he visited

some of the POW camps in Germany. Harte and Phildius toured the Soldatenheim at Döberitz on March 3.

They met some Russian POWs who had jobs tending the garden at the center. The president of the Association

offered to introduce the American secretaries to the general in command of the POW camp system in Prussia,

and encouraged the American YMCA to erect huts in the prison camp. The six thousand British POWs, over four thousand Russian

prisoners, and two thousand French POWs in this camp would benefit from Red Triangle services. Harte and Phildius provided

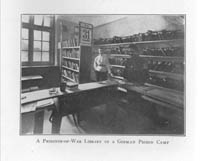

some spiritual relief for the POWs at the camp. They conducted funeral services for two British prisoners, and

promised to contact their families. The next day, they visited the British civilian prisoners at Ruhleben, which

had been a horseracing track before the war. The two secretaries found the camp well organized, with an extensive

night school, a choir that performed at weekly concerts and Sunday services, and a library of 1,500 volumes.

Before Harte received permission from the Ministry of War to begin Association work in prison facilities, he visited

some of the POW camps in Germany. Harte and Phildius toured the Soldatenheim at Döberitz on March 3.

They met some Russian POWs who had jobs tending the garden at the center. The president of the Association

offered to introduce the American secretaries to the general in command of the POW camp system in Prussia,

and encouraged the American YMCA to erect huts in the prison camp. The six thousand British POWs, over four thousand Russian

prisoners, and two thousand French POWs in this camp would benefit from Red Triangle services. Harte and Phildius provided

some spiritual relief for the POWs at the camp. They conducted funeral services for two British prisoners, and

promised to contact their families. The next day, they visited the British civilian prisoners at Ruhleben, which

had been a horseracing track before the war. The two secretaries found the camp well organized, with an extensive

night school, a choir that performed at weekly concerts and Sunday services, and a library of 1,500 volumes.

The camp represented a mixture of every class in society, from nobility and wealth to common servants. Many

POWs had money, and those without funds received five Marks each week from the British government through the

U.S. embassy. The prisoners also had sufficient clothing; most requests were for tobacco. Unlike military war

prisoners, civilian internees were shocked by their unexpected incarceration in early August 1914. The British

civilians expected the war to end within a few months, and as the war dragged on, their mental and spiritual

fortitude dwindled. The prisoners also chafed under the poor living conditions (men lived six to a horse stall,

or by the hundreds in the hay lofts). Even more grating was the German insistence at the beginning of the war

on rigid military discipline for internees, which soured relations between the guards and the prisoners. English

internees desperately needed the services provided by the YMCA. The POWs were enthusiastic about Harte's visit,

and informed him that they were interested in applying for an Association building. Ruhleben was clearly a field

of future Red Triangle work. Harte concluded that, for the Association to succeed in POW relief work, the

International Committee would have to send at least one experienced secretary who spoke French, one who spoke

Russian, and one who could supervise office work and bookkeeping requirements.15

The camp represented a mixture of every class in society, from nobility and wealth to common servants. Many

POWs had money, and those without funds received five Marks each week from the British government through the

U.S. embassy. The prisoners also had sufficient clothing; most requests were for tobacco. Unlike military war

prisoners, civilian internees were shocked by their unexpected incarceration in early August 1914. The British

civilians expected the war to end within a few months, and as the war dragged on, their mental and spiritual

fortitude dwindled. The prisoners also chafed under the poor living conditions (men lived six to a horse stall,

or by the hundreds in the hay lofts). Even more grating was the German insistence at the beginning of the war

on rigid military discipline for internees, which soured relations between the guards and the prisoners. English

internees desperately needed the services provided by the YMCA. The POWs were enthusiastic about Harte's visit,

and informed him that they were interested in applying for an Association building. Ruhleben was clearly a field

of future Red Triangle work. Harte concluded that, for the Association to succeed in POW relief work, the

International Committee would have to send at least one experienced secretary who spoke French, one who spoke

Russian, and one who could supervise office work and bookkeeping requirements.15

16

On the evening of March 4, Harte and Phildius had dinner with Pastor Kieser, Franz Spemann, and Herr Sudreitzky

of the German Christian Student Movement (Deutsche Christlicher Studenten Vereine, or DCSV). They were

joined by two Swedish missionaries who were interested in working with Greek POWs in Germany. Sudreitzky had

already begun relief work among Russian prisoners. Kieser, Spemann, and Gerhard Niedermeyer (National Secretary

of the DCSV) were very enthusiastic about conducting welfare work for students in the war prisoner population.

They believed that YMCA work for these POWs would facilitate friendlier post-war relations. Spemann offered his

services to the American YMCA for POW work if the International Committee paid half of his salary. Kieser was

willing to work with Belgian student POWs for six months before he became the Home Secretary of the Basel Mission.

By this time, the DCSV was already engaged in work with Allied prisoners in Germany. The DCSV had received permission

from the Ministry of War to distribute New Testaments to Russian prisoners. Pastor Schrenk and three assistants

distributed over 250,000 Testaments. Schrenk was a member of the Relief Committee for the Pastoral Work in German

Prisoners' Camps, and was in a unique position to promote POW relief. The DCSV assigned three secretaries to assist

Schrenk and paid their salaries. They would focus on developing social work as part of the relief effort in prison

camps.

On the evening of March 4, Harte and Phildius had dinner with Pastor Kieser, Franz Spemann, and Herr Sudreitzky

of the German Christian Student Movement (Deutsche Christlicher Studenten Vereine, or DCSV). They were

joined by two Swedish missionaries who were interested in working with Greek POWs in Germany. Sudreitzky had

already begun relief work among Russian prisoners. Kieser, Spemann, and Gerhard Niedermeyer (National Secretary

of the DCSV) were very enthusiastic about conducting welfare work for students in the war prisoner population.

They believed that YMCA work for these POWs would facilitate friendlier post-war relations. Spemann offered his

services to the American YMCA for POW work if the International Committee paid half of his salary. Kieser was

willing to work with Belgian student POWs for six months before he became the Home Secretary of the Basel Mission.

By this time, the DCSV was already engaged in work with Allied prisoners in Germany. The DCSV had received permission

from the Ministry of War to distribute New Testaments to Russian prisoners. Pastor Schrenk and three assistants

distributed over 250,000 Testaments. Schrenk was a member of the Relief Committee for the Pastoral Work in German

Prisoners' Camps, and was in a unique position to promote POW relief. The DCSV assigned three secretaries to assist

Schrenk and paid their salaries. They would focus on developing social work as part of the relief effort in prison

camps.

The DCSV recognized that thousands of prisoners did not receive parcels from home and were destitute. They needed

additional food and clothing, and the organization hoped to help these men. In addition, the DCSV sought to

establish libraries for German guards detailed to POW camps. Guards faced the same boredom as prisoners, and

this program was met with great national sympathy and support. Providing books to guards also gave the DCSV

another avenue for gaining access to prison camps. While the DCSV was eager to undertake these social programs

(building YMCA halls, equipping orchestras and libraries, and compensating German secretaries), the organization

faced financial handicaps. The fiscal strength of the nation was directed toward the economic maintenance of

Germany and the relief of German soldiers in the field. As a result, the DCSV looked to the American YMCA for

financial assistance to support this program. Mott provided $5,000 in May 1915, and continued to extend funds

needed to maintain German YMCA social work until February 1917. Members of the German YMCA were aware of the

problems that POWs faced, and were interested in extending as much assistance as possible.16

The DCSV recognized that thousands of prisoners did not receive parcels from home and were destitute. They needed

additional food and clothing, and the organization hoped to help these men. In addition, the DCSV sought to

establish libraries for German guards detailed to POW camps. Guards faced the same boredom as prisoners, and

this program was met with great national sympathy and support. Providing books to guards also gave the DCSV

another avenue for gaining access to prison camps. While the DCSV was eager to undertake these social programs

(building YMCA halls, equipping orchestras and libraries, and compensating German secretaries), the organization

faced financial handicaps. The fiscal strength of the nation was directed toward the economic maintenance of

Germany and the relief of German soldiers in the field. As a result, the DCSV looked to the American YMCA for

financial assistance to support this program. Mott provided $5,000 in May 1915, and continued to extend funds

needed to maintain German YMCA social work until February 1917. Members of the German YMCA were aware of the

problems that POWs faced, and were interested in extending as much assistance as possible.16

17

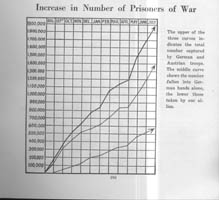

The American secretary took an optimistic view of the work ahead and sought to build up a strong relationship with

German authorities. He wrote on February 23 that, "all prisoners here are treated justly, and there is no foundation

at all for the dreadful stories that have been circulated in other lands." By February 1915, the Germans and

Austro-Hungarians held approximately one million Allied prisoners, and the problem of providing relief services to

so great a number was "vast and complicated." The YMCA was in a unique position to provide assistance to these

The American secretary took an optimistic view of the work ahead and sought to build up a strong relationship with

German authorities. He wrote on February 23 that, "all prisoners here are treated justly, and there is no foundation

at all for the dreadful stories that have been circulated in other lands." By February 1915, the Germans and

Austro-Hungarians held approximately one million Allied prisoners, and the problem of providing relief services to

so great a number was "vast and complicated." The YMCA was in a unique position to provide assistance to these

… young men in a trying position. In a military prison, character must either grow in strength or disintegrate. There was no question, if the Association could get permission, to render a fraternal service to help in character-building. The sure way to help prisoners-of-war was to build up their faith and occupy their time with work, study, and recreation.17

Harte also noted that the development of American YMCA work in Germany faced serious constraints. Space, in the

form of rooms and huts, was extremely limited in prison camps. The lack of adequate experienced personnel was an

even a greater problem. Workers trained in social service were needed to provide personal service to these prisoners.

Reading matter, especially light literature that made no reference to the war, would be very useful. But most

importantly, at least for the YMCA, the POWs needed religious literature, including English, French, and Russian

Bibles and Testaments, which could be provided by the American Bible Society and the World's Sunday School

Association.18

Harte also noted that the development of American YMCA work in Germany faced serious constraints. Space, in the

form of rooms and huts, was extremely limited in prison camps. The lack of adequate experienced personnel was an

even a greater problem. Workers trained in social service were needed to provide personal service to these prisoners.

Reading matter, especially light literature that made no reference to the war, would be very useful. But most

importantly, at least for the YMCA, the POWs needed religious literature, including English, French, and Russian

Bibles and Testaments, which could be provided by the American Bible Society and the World's Sunday School

Association.18

18

On March 16, Harte cabled the International Committee about the conference regarding Association work in Germany.

The Ministry of War recommended that work should begin at the camp in Göttingen, which held approximately

seven thousand Russian, British, French, Belgian, and civilian prisoners, and in Altengrabow, where over twenty thousand Russian,

French, Belgian, British, and civilian POWs were incarcerated. He requested salaries for three German assistants

who could speak Russian, French, and English, respectively. Harte also asked Mott to inform the British, French,

and Russian governments about this breakthrough in POW diplomacy. He had already contacted Gerard, who would forward

a report to the U.S. State Department. In a letter,

On March 16, Harte cabled the International Committee about the conference regarding Association work in Germany.

The Ministry of War recommended that work should begin at the camp in Göttingen, which held approximately

seven thousand Russian, British, French, Belgian, and civilian prisoners, and in Altengrabow, where over twenty thousand Russian,

French, Belgian, British, and civilian POWs were incarcerated. He requested salaries for three German assistants

who could speak Russian, French, and English, respectively. Harte also asked Mott to inform the British, French,

and Russian governments about this breakthrough in POW diplomacy. He had already contacted Gerard, who would forward

a report to the U.S. State Department. In a letter,

Harte followed up with more detailed information. Phildius and he planned to build two Association huts in

Göttingen and Altengrabow; they would also prepare demonstration pilot projects for German authorities by

organizing and supporting YMCA committees in these camps. In addition, Harte had enlisted the services of the

former secretary of the German YMCA in London, the former secretary of the German Association in St. Petersburg,

and a German secretary from the Student Christian Federation.19

Harte followed up with more detailed information. Phildius and he planned to build two Association huts in

Göttingen and Altengrabow; they would also prepare demonstration pilot projects for German authorities by

organizing and supporting YMCA committees in these camps. In addition, Harte had enlisted the services of the

former secretary of the German YMCA in London, the former secretary of the German Association in St. Petersburg,

and a German secretary from the Student Christian Federation.19

19

Harte and Phildius left Berlin on March 14 to visit the prison camp at Göttingen. They were accompanied

by Captain W. von Lübbers, a representative assigned by the Ministry of War as a military escort. They

arrived at the camp on March 22 and conducted an inspection. At a meeting attended by von Lübbers, Colonel

Bogen (the camp commandant), Professor Carl Stange of the University of Göttingen, Schreiber, Phildius,

and Harte, the delegates studied the problem of providing aid to the POWs. Harte reported that German officials

were very sympathetic to the Association's plan, and that Bogen was interested in every phase of welfare work.

Stange was eager to serve the POWs, and had prepared the ground for the Association by offering weekly lectures,

publishing a magazine fortnightly in French, and starting a small library.

Harte and Phildius left Berlin on March 14 to visit the prison camp at Göttingen. They were accompanied

by Captain W. von Lübbers, a representative assigned by the Ministry of War as a military escort. They

arrived at the camp on March 22 and conducted an inspection. At a meeting attended by von Lübbers, Colonel

Bogen (the camp commandant), Professor Carl Stange of the University of Göttingen, Schreiber, Phildius,

and Harte, the delegates studied the problem of providing aid to the POWs. Harte reported that German officials

were very sympathetic to the Association's plan, and that Bogen was interested in every phase of welfare work.

Stange was eager to serve the POWs, and had prepared the ground for the Association by offering weekly lectures,

publishing a magazine fortnightly in French, and starting a small library.

The commandant provided a choice site for a YMCA hut, and Harte hoped to open the building within two weeks.

Von Lübbers informed Harte of his report to his superiors regarding recent developments. All the German

officials were impressed with the Association secretaries and only wished that the work had begun earlier; the

American YMCA was assured that it could rely on all possible support from the Ministry of War. In letters dated

March 24 and 30, Harte described conditions at Göttingen. He believed that the Ministry of War was "more

than keeping international agreements," and that they sought to help POWs, constantly making improvements. The

barracks at Göttingen were the best he had seen to date. The camp had

bathing and laundry facilities, as well as repair shops for clothing and shoes. The hospital was clean and

attractive, with an adequate staff of doctors and nurses. Prisoners received regulation issues of clothing and

blankets, although there was always a need for socks and shoes. Rations were the same in Germany as he had observed

in England, although "I knew I would be sorry to have the war prison fare every day for a week."20

The commandant provided a choice site for a YMCA hut, and Harte hoped to open the building within two weeks.

Von Lübbers informed Harte of his report to his superiors regarding recent developments. All the German

officials were impressed with the Association secretaries and only wished that the work had begun earlier; the

American YMCA was assured that it could rely on all possible support from the Ministry of War. In letters dated

March 24 and 30, Harte described conditions at Göttingen. He believed that the Ministry of War was "more

than keeping international agreements," and that they sought to help POWs, constantly making improvements. The

barracks at Göttingen were the best he had seen to date. The camp had

bathing and laundry facilities, as well as repair shops for clothing and shoes. The hospital was clean and

attractive, with an adequate staff of doctors and nurses. Prisoners received regulation issues of clothing and

blankets, although there was always a need for socks and shoes. Rations were the same in Germany as he had observed

in England, although "I knew I would be sorry to have the war prison fare every day for a week."20

20

Three days later, the two Association secretaries, Schreiber, and von Lübbers traveled to Crossen-an-der-Oder

to inspect that prison camp. For an undisclosed reason, the Germans decided to develop this camp instead of Altengrabow.

They were met by the commandant and his staff, who were quite proud of their camp. Harte was impressed with the reception

he received from German authorities. The Association secretaries inspected the kitchen and had a lunch of broth and

sandwiches. They also toured the camp's bathing and fumigating plant; camp officers described how the Russian POWs

initially refused to enter the bathing facility, and many tried to escape. After they endured the process, they had

learned to look forward to weekly cleaning. The camp also featured a wood-working department where prisoners could

build small toys, inlaid chests, chairs, and camp furniture. The camp fire brigade demonstrated an exercise for the

visitors. These activities gave prisoners physical and mental stimulation while providing important services for the

camp. In addition, the Germans provided a church for the POWs based on a Russian design.21

Three days later, the two Association secretaries, Schreiber, and von Lübbers traveled to Crossen-an-der-Oder

to inspect that prison camp. For an undisclosed reason, the Germans decided to develop this camp instead of Altengrabow.

They were met by the commandant and his staff, who were quite proud of their camp. Harte was impressed with the reception

he received from German authorities. The Association secretaries inspected the kitchen and had a lunch of broth and

sandwiches. They also toured the camp's bathing and fumigating plant; camp officers described how the Russian POWs

initially refused to enter the bathing facility, and many tried to escape. After they endured the process, they had

learned to look forward to weekly cleaning. The camp also featured a wood-working department where prisoners could

build small toys, inlaid chests, chairs, and camp furniture. The camp fire brigade demonstrated an exercise for the

visitors. These activities gave prisoners physical and mental stimulation while providing important services for the

camp. In addition, the Germans provided a church for the POWs based on a Russian design.21

21

On April 8, Harte reported that the camp commandants at Göttingen and Crossen had received him most cordially

and had given him the freedom of the camps. They were "scientifically studying the improvement of conditions,

physically, mentally, and spiritually." Harte attended their meetings and was allowed to participate in discussions.

He wrote the next day:

On April 8, Harte reported that the camp commandants at Göttingen and Crossen had received him most cordially

and had given him the freedom of the camps. They were "scientifically studying the improvement of conditions,

physically, mentally, and spiritually." Harte attended their meetings and was allowed to participate in discussions.

He wrote the next day:

Everywhere I go I find the prison officials courteous. Many go out of their way to help us. Throughout official circles the sentiment is to do for war prisoners all that they can. If the news concerning the treatment of war prisoners in other countries continues to be good, we will advance rapidly.22

The American secretary described the essence of the Principle of Reciprocity. By gaining access to German prison camps to provide welfare services to Allied prisoners, he hoped to persuade the British and French governments (and other belligerent states in the future) to open their prison camps to Red Triangle secretaries so that German POWs could benefit from the Association program.23

22

Harte also traveled to Hannoverisch-Münden on March 29 and found the POWs in need of a reading room,

prayer room, and lecture hall. The camp commandant heartily encouraged Association work, and urged Harte to

begin as soon as possible. The American secretary concluded that service in this camp was:

Harte also traveled to Hannoverisch-Münden on March 29 and found the POWs in need of a reading room,

prayer room, and lecture hall. The camp commandant heartily encouraged Association work, and urged Harte to

begin as soon as possible. The American secretary concluded that service in this camp was:

… a remarkable opportunity to serve Russia as well as other lands now at war. If we minister to Russians in the war prisons here it must not only give us access to Germans in Russia, but it must be of great service to the YMCA in Russia in future years … I believe we are having a remarkable opportunity today.24

Encouraged by his progress in Germany, Harte realized that the next step was to provide services to German POWs in Russia, invoking the Principle of Reciprocity. The establishment of Red Triangle welfare work in Russia could be used to request even greater concessions in Germany from the Ministry of War. In addition, the expansion of POW work to Russia would help to build up the Russian YMCA (Miyak) and prepare the organization for post-war growth. Harte planned to discuss expanding Association POW work to Russia with Ambassador Gerard and sought embassy support.25

23

By the middle of April 1915, Harte had visited additional prison camps near Cassel and Sennelager. While visiting

these camps, Harte distributed money to non-commissioned officers for the purchase of articles and goods needed by

the POWs. At Cassel, the sergeant in charge purchased barber instruments, soap, blacking, and brushes for use by

POWs who could not afford them.

By the middle of April 1915, Harte had visited additional prison camps near Cassel and Sennelager. While visiting

these camps, Harte distributed money to non-commissioned officers for the purchase of articles and goods needed by

the POWs. At Cassel, the sergeant in charge purchased barber instruments, soap, blacking, and brushes for use by

POWs who could not afford them.

In addition, Harte arranged for the distribution of Gospels among the men. After the inspections, he issued similar

optimistic reports, which became the target of criticism after the war. But Harte was working under trying circumstances.

Harte sent copies of his correspondence to the International Committee in New York, various U.S. embassies, and the

German government to avoid any suspicions regarding his work.

In addition, Harte arranged for the distribution of Gospels among the men. After the inspections, he issued similar

optimistic reports, which became the target of criticism after the war. But Harte was working under trying circumstances.

Harte sent copies of his correspondence to the International Committee in New York, various U.S. embassies, and the

German government to avoid any suspicions regarding his work.

24

His reports were tactful and diplomatic as he tried to establish a working relationship with the German government.

Harte recognized that unfavorable reports would close German prison camps to the American YMCA, cutting off essential

services to Allied prisoners. In addition, his views reflected the optimistic nature of Association secretaries, who

tended to view challenges as opportunities. Harte's descriptions of the humane attitude of German officials and their

promotion of the POW welfare program were followed up by active policy implementation. The American secretary also

recognized the strain Allied POWs were placing on the German economy. By April 1915, the Germans officially held

812,800 prisoners in approximately one hundred major prison camps; there were more Allied POWs than the peacetime footing of

the German Army (806,026 officers and men in

His reports were tactful and diplomatic as he tried to establish a working relationship with the German government.

Harte recognized that unfavorable reports would close German prison camps to the American YMCA, cutting off essential

services to Allied prisoners. In addition, his views reflected the optimistic nature of Association secretaries, who

tended to view challenges as opportunities. Harte's descriptions of the humane attitude of German officials and their

promotion of the POW welfare program were followed up by active policy implementation. The American secretary also

recognized the strain Allied POWs were placing on the German economy. By April 1915, the Germans officially held

812,800 prisoners in approximately one hundred major prison camps; there were more Allied POWs than the peacetime footing of

the German Army (806,026 officers and men in

1914). To administer support for this body of captives, the Prisoner's Commission of the Ministry of War employed

over six hundred men in headquarters work alone at a cost of 1.5 million Marks a day. Harte remarked, "To house, feed,

clothe, and watch over 800,000 is a considerable task. I wonder Germany is doing it as well as she

does."26 The American secretary pointed out that the Germans focused on

improving sanitary conditions in the prison camps. Russian prisoners arrived at POW camps infested with vermin and

medical authorities were dedicated to preventing further outbreaks of typhoid. He also acknowledged that even if

the Germans exceeded the requirements of the Hague Conventions, there would still be a dire need for the type of

relief work provided by the YMCA.27

1914). To administer support for this body of captives, the Prisoner's Commission of the Ministry of War employed

over six hundred men in headquarters work alone at a cost of 1.5 million Marks a day. Harte remarked, "To house, feed,

clothe, and watch over 800,000 is a considerable task. I wonder Germany is doing it as well as she

does."26 The American secretary pointed out that the Germans focused on

improving sanitary conditions in the prison camps. Russian prisoners arrived at POW camps infested with vermin and

medical authorities were dedicated to preventing further outbreaks of typhoid. He also acknowledged that even if

the Germans exceeded the requirements of the Hague Conventions, there would still be a dire need for the type of

relief work provided by the YMCA.27

25

By mid-March 1915, Harte had formulated a general plan for undertaking POW work in Germany. He knew that American

secretaries could provide an invaluable service to Allied prisoners in Germany, but he also recognized that the

International Committee would be unlikely to provide enough men to establish services in all of Germany's prison

camps. Instead, he recommended that a limited number of Red Triangle workers form executive committees from among

the POWs to manage the welfare work. The American Association could then concentrate on funding and equipping huts

with exchange libraries, small organs, gymnastic and sports equipment, testaments and psalms, school textbooks, and

hymn books. The American secretary also discussed the issue of clothing with von Lübbers. Crown Princess Margaret

of Sweden had already begun organizing circles to provide clothing for Allied prisoners in Germany, and was willing to

work with the American YMCA to distribute goods to the needy.28

By mid-March 1915, Harte had formulated a general plan for undertaking POW work in Germany. He knew that American

secretaries could provide an invaluable service to Allied prisoners in Germany, but he also recognized that the

International Committee would be unlikely to provide enough men to establish services in all of Germany's prison

camps. Instead, he recommended that a limited number of Red Triangle workers form executive committees from among

the POWs to manage the welfare work. The American Association could then concentrate on funding and equipping huts

with exchange libraries, small organs, gymnastic and sports equipment, testaments and psalms, school textbooks, and

hymn books. The American secretary also discussed the issue of clothing with von Lübbers. Crown Princess Margaret

of Sweden had already begun organizing circles to provide clothing for Allied prisoners in Germany, and was willing to

work with the American YMCA to distribute goods to the needy.28

The French Government's Response

26

While Harte worked in Germany, Hibbard inspected prison camp conditions in France. Although he found the physical

conditions excellent, the American secretary determined that German POWs needed services that the French government

could not provide. Many interned civilians were destitute, and French authorities issued appeals for books and games

for the internees. The French had placed civilians in many small camps scattered across the country, so that Hibbard

concluded that the establishment of huts would not be practical. Instead, the American secretary recommended that the

Association distribute circulating libraries, games, and a traveling Field Secretary to support a Red Triangle program.

These prisoners did not have access to current periodicals or books, and circulating libraries would provide them with

an important means of diversion. Hibbard also found that Central Power POWs in military prisons also were in great need

of Association social work. He believed that the establishment of YMCA huts would be far more beneficial for these

unfortunates, especially in the larger prison camps. The men had access to only limited correspondence; they could send

only two postcards and one letter per month, and French censors could not handle additional correspondence. As a result,

Hibbard recommended that the YMCA begin distributing libraries and games among the military POWs as well.29

While Harte worked in Germany, Hibbard inspected prison camp conditions in France. Although he found the physical

conditions excellent, the American secretary determined that German POWs needed services that the French government

could not provide. Many interned civilians were destitute, and French authorities issued appeals for books and games

for the internees. The French had placed civilians in many small camps scattered across the country, so that Hibbard

concluded that the establishment of huts would not be practical. Instead, the American secretary recommended that the

Association distribute circulating libraries, games, and a traveling Field Secretary to support a Red Triangle program.

These prisoners did not have access to current periodicals or books, and circulating libraries would provide them with

an important means of diversion. Hibbard also found that Central Power POWs in military prisons also were in great need

of Association social work. He believed that the establishment of YMCA huts would be far more beneficial for these

unfortunates, especially in the larger prison camps. The men had access to only limited correspondence; they could send

only two postcards and one letter per month, and French censors could not handle additional correspondence. As a result,

Hibbard recommended that the YMCA begin distributing libraries and games among the military POWs as well.29

27

The World's Alliance of YMCAs also assisted Hibbard in developing POW work in France. The Swiss National YMCA Committee

sent Pastor Lauterbach, a clergyman from Berne, to Paris to conduct evangelistic work among German prisoners. The German

government approved Lauterbach for this work. Lauterbach had connections with Student Associations, and he was further

suited for this work because he spoke French, German, and English. Sautter also requested additional secretaries for POW

work from the World's Alliance. Pastor W. Gottsched, who responded to Sautter's telegram, considered the call a "divine

commission." Gottsched was well received by the Ministry of War because of his strong French sympathies, although he

proved his ability to work with the German POWs. With the assistance of Harte, Gottsched improved relations with both

the War Ministry and Ambassador Sharp's staff and obtained greater access to prison facilities. At this point, Hibbard

hoped to coordinate the activities between the French chaplains, the Swiss secretaries, and the American Red Triangle

workers to reduce duplicated effort and avoid dangerous errors, but important problems had to be addressed before the

work could expand. With the cooperation of Raoul Allier, leader of the French Federation of Christian Students and

ardent supporter of French prisoners of war in Germany, the French YMCA obtained four thousand books on a variety of subjects

from several large publishers in Paris for French prisoners in Germany. The books were shipped via the World's Committee

in Geneva, and sent under the cover of the Red Cross to POWs incarcerated in German prison camps. The American YMCA

defrayed the costs of purchase and shipment of these books, and each book was stamped with the American YMCA

emblem.30

The World's Alliance of YMCAs also assisted Hibbard in developing POW work in France. The Swiss National YMCA Committee

sent Pastor Lauterbach, a clergyman from Berne, to Paris to conduct evangelistic work among German prisoners. The German

government approved Lauterbach for this work. Lauterbach had connections with Student Associations, and he was further

suited for this work because he spoke French, German, and English. Sautter also requested additional secretaries for POW

work from the World's Alliance. Pastor W. Gottsched, who responded to Sautter's telegram, considered the call a "divine

commission." Gottsched was well received by the Ministry of War because of his strong French sympathies, although he

proved his ability to work with the German POWs. With the assistance of Harte, Gottsched improved relations with both

the War Ministry and Ambassador Sharp's staff and obtained greater access to prison facilities. At this point, Hibbard

hoped to coordinate the activities between the French chaplains, the Swiss secretaries, and the American Red Triangle

workers to reduce duplicated effort and avoid dangerous errors, but important problems had to be addressed before the

work could expand. With the cooperation of Raoul Allier, leader of the French Federation of Christian Students and

ardent supporter of French prisoners of war in Germany, the French YMCA obtained four thousand books on a variety of subjects

from several large publishers in Paris for French prisoners in Germany. The books were shipped via the World's Committee

in Geneva, and sent under the cover of the Red Cross to POWs incarcerated in German prison camps. The American YMCA

defrayed the costs of purchase and shipment of these books, and each book was stamped with the American YMCA

emblem.30

28

In the meantime, Harte had received additional concessions from the German Ministry of War in early March 1915.

With this news, Hibbard put pressure on the French government to fulfill the quid pro quo clause of reciprocal

treatment in the February 23 agreement. French officials, however, delayed a decision on further concessions because

of widespread dissatisfaction among the French public that prison conditions in Germany were far worse than for Central

Power prisoners in France. The basis of reciprocity rested on the concept that it "will … be possible to do

Association work for prisoners in any country only so far as we can give assurances that the enemy country makes

similar concessions."31

In the meantime, Harte had received additional concessions from the German Ministry of War in early March 1915.

With this news, Hibbard put pressure on the French government to fulfill the quid pro quo clause of reciprocal

treatment in the February 23 agreement. French officials, however, delayed a decision on further concessions because

of widespread dissatisfaction among the French public that prison conditions in Germany were far worse than for Central

Power prisoners in France. The basis of reciprocity rested on the concept that it "will … be possible to do

Association work for prisoners in any country only so far as we can give assurances that the enemy country makes

similar concessions."31

29

The chief difficulty with reciprocity was that most people believed that the prisoners under their care were treated

better than their countrymen held in enemy territory. French authorities were not disposed to facilitate concessions

to POWs in their system, even if the German government liberalized access to the American YMCA. While the Germans might

concede some advantages to French prisoners, this act compensated only in a very small degree for the material privations

which the Allied prisoners suffered in comparison with German POWs incarcerated in France.32

The chief difficulty with reciprocity was that most people believed that the prisoners under their care were treated

better than their countrymen held in enemy territory. French authorities were not disposed to facilitate concessions

to POWs in their system, even if the German government liberalized access to the American YMCA. While the Germans might

concede some advantages to French prisoners, this act compensated only in a very small degree for the material privations

which the Allied prisoners suffered in comparison with German POWs incarcerated in France.32

30

The other major obstacle was the sheer physical challenge created by the scope of the POW situation in France and

the government's labor policy. Hibbard quickly recognized the problems that the American embassy staff encountered

in administering to the needs of hundreds of thousands of Central Power war prisoners. The Ministry of War had

established approximately ninety major prison camps across the country to house about four hundred thousand Central Powers POWs by

the end of the war. In addition, the French military maintained four prison camps on Corsica, and twenty-seven prison

camps in North Africa (three in Tunisia, thirteen in Algeria, and eleven in French Morocco). The YMCA would need a large

body of field secretaries to visit and organize Association programs in French prison camps. To compound the problem of

the size of the prison population, the French employed their prisoner rank and file in labor detachments that scattered

prisoners across the country. Instead of concentrating a large number of POWs in a small number of camps, prisoners worked

in large numbers of work parties that moved according to the seasons or construction schedules. While the German

government agreed to the construction of YMCA huts in several prison camps, Association leaders in France considered

the acquisition of such halls as less practical.33

The other major obstacle was the sheer physical challenge created by the scope of the POW situation in France and

the government's labor policy. Hibbard quickly recognized the problems that the American embassy staff encountered

in administering to the needs of hundreds of thousands of Central Power war prisoners. The Ministry of War had

established approximately ninety major prison camps across the country to house about four hundred thousand Central Powers POWs by