Table of Contents

Chapter 11

Expanding WPA Relief Work: Addressing the Needs of Political Prisoners and Labor Detachments

1

During the course of World War I, the monumental task of feeding and caring for millions of war prisoners took a heavy

economic toll on the Central Powers. Faced with the Allied blockade, the German and Austro-Hungarian governments took

two steps to alleviate the situation. The first was a political solution in which the Central Powers actively recruited

volunteer troops from dissident minorities among the Allied prisoners. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians set up special

"propaganda camps," where conditions were far superior to those in most military POW facilities. They sent minority

groups-especially Irish, Muslim, Polish, and Ukrainian prisoners-to these camps, where they received improved rations,

entertainment, and special privileges. The Central Powers' goal was to recruit these men to join special national

detachments and fight for the independence of their subjected nations. Instead of being burdens to the Central Power

economies, these men would take up arms and fight for the independence of Ireland, North Africa, Central Asia, Russian

Poland, and the Ukraine. This policy was derived from President Woodrow Wilson's doctrine of "national self-determination,"

except that the Central Powers hoped to set up a post-war political and economic system in Europe based on vassal kingdoms

and satellite states. American YMCA secretaries recognized the special problems these POWs faced, caught between the loyalty

they had sworn to the Allied governments and the contempt they faced from other Allied prisoners. While not suffering from

as many physical problems, these prisoners faced strong mental pressures.

During the course of World War I, the monumental task of feeding and caring for millions of war prisoners took a heavy

economic toll on the Central Powers. Faced with the Allied blockade, the German and Austro-Hungarian governments took

two steps to alleviate the situation. The first was a political solution in which the Central Powers actively recruited

volunteer troops from dissident minorities among the Allied prisoners. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians set up special

"propaganda camps," where conditions were far superior to those in most military POW facilities. They sent minority

groups-especially Irish, Muslim, Polish, and Ukrainian prisoners-to these camps, where they received improved rations,

entertainment, and special privileges. The Central Powers' goal was to recruit these men to join special national

detachments and fight for the independence of their subjected nations. Instead of being burdens to the Central Power

economies, these men would take up arms and fight for the independence of Ireland, North Africa, Central Asia, Russian

Poland, and the Ukraine. This policy was derived from President Woodrow Wilson's doctrine of "national self-determination,"

except that the Central Powers hoped to set up a post-war political and economic system in Europe based on vassal kingdoms

and satellite states. American YMCA secretaries recognized the special problems these POWs faced, caught between the loyalty

they had sworn to the Allied governments and the contempt they faced from other Allied prisoners. While not suffering from

as many physical problems, these prisoners faced strong mental pressures.

2

The second step in alleviating the POW burden was employing the prisoners as laborers to replace Germans mobilized for

the war effort. Under the Hague Conventions, the use of POW labor was clearly defined. Work was mandatory for all healthy

enlisted men and voluntary for non-commissioned officers, although employment in the war industries (munitions plants and

armament factories) and near the front lines was prohibited. Both the Allies and Central Powers violated these conventions.

Work conditions in the Central Powers varied greatly, from horrendous (for prisoners working in the German salt mines) to

healthy (for POWs employed in agriculture). The American YMCA secretaries applauded the German government's decision to put

as many prisoners to work as possible. Prisoners could leave the confines of the barbed-wire compounds, get into new

surroundings, and work for extra money. But there were serious problems for the Association in serving labor detachments.

Men were no longer concentrated in prison camps, but dispersed across the countryside, which made YMCA relief operations

far more difficult. Secretaries had to travel even farther to contact smaller numbers of prisoners. The Association had

to devise new methods to maintain contact with Allied prisoners in work detachments.

The second step in alleviating the POW burden was employing the prisoners as laborers to replace Germans mobilized for

the war effort. Under the Hague Conventions, the use of POW labor was clearly defined. Work was mandatory for all healthy

enlisted men and voluntary for non-commissioned officers, although employment in the war industries (munitions plants and

armament factories) and near the front lines was prohibited. Both the Allies and Central Powers violated these conventions.

Work conditions in the Central Powers varied greatly, from horrendous (for prisoners working in the German salt mines) to

healthy (for POWs employed in agriculture). The American YMCA secretaries applauded the German government's decision to put

as many prisoners to work as possible. Prisoners could leave the confines of the barbed-wire compounds, get into new

surroundings, and work for extra money. But there were serious problems for the Association in serving labor detachments.

Men were no longer concentrated in prison camps, but dispersed across the countryside, which made YMCA relief operations

far more difficult. Secretaries had to travel even farther to contact smaller numbers of prisoners. The Association had

to devise new methods to maintain contact with Allied prisoners in work detachments.

3

In addition, this study has focused primarily on the POW policies of the Prussian government. The American YMCA also

had to deal with the lesser German kingdoms in order to expand WPA operations across the entire German Empire during

the war. Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg maintained independent Ministries of War after German unification in 1871,

and they controlled large numbers of Allied prisoners. The Association had to negotiate with these governments to gain

access to POWs and to provide WPA services.

In addition, this study has focused primarily on the POW policies of the Prussian government. The American YMCA also

had to deal with the lesser German kingdoms in order to expand WPA operations across the entire German Empire during

the war. Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg maintained independent Ministries of War after German unification in 1871,

and they controlled large numbers of Allied prisoners. The Association had to negotiate with these governments to gain

access to POWs and to provide WPA services.

The American YMCA and German Propaganda Camps

4

While some Allied prisoners suffered in reprisal camps because of perceived violations of international agreements

by Allied captors of Central Power prisoners, selected POWs received special treatment for political reasons. The

Germans concentrated nationalities and classes considered receptive to German influence, and assigned Irish,

Flemish, Ukrainians, White Russians, German Russians, and Muslim prisoners itoseparate prison camps. At these propaganda

camps, POWs enjoyed better rations, improved accommodations, recreational facilities, and educational programs designed

to gain the prisoners' sympathetic support for the German war effort. These prisons were made as comfortable as possible

for these special prisoners. The German military designed propaganda camps with several objectives in mind. First, they

sought to impress the prisoners with the high state of German Kultur. The Germans had no doubt that they would

eventually triumph in the war, and they tried to convince prisoners that by siding with the Germans they could share in

that ultimate victory. The Germans also recruited volunteers to join the ranks of their allies' armies. They would fight to

liberate their homelands, or to prevent infidels from seizing holy lands. Converted prisoners could also act as underground

agents, sent behind the Allied lines to stir up dissent, especially within minority nationalities. From a more long-term

perspective, the Germans planned to establish friendly relations with these prisoners so that when they returned home

after a German victory, they would serve German interests in the occupied territories.1

While some Allied prisoners suffered in reprisal camps because of perceived violations of international agreements

by Allied captors of Central Power prisoners, selected POWs received special treatment for political reasons. The

Germans concentrated nationalities and classes considered receptive to German influence, and assigned Irish,

Flemish, Ukrainians, White Russians, German Russians, and Muslim prisoners itoseparate prison camps. At these propaganda

camps, POWs enjoyed better rations, improved accommodations, recreational facilities, and educational programs designed

to gain the prisoners' sympathetic support for the German war effort. These prisons were made as comfortable as possible

for these special prisoners. The German military designed propaganda camps with several objectives in mind. First, they

sought to impress the prisoners with the high state of German Kultur. The Germans had no doubt that they would

eventually triumph in the war, and they tried to convince prisoners that by siding with the Germans they could share in

that ultimate victory. The Germans also recruited volunteers to join the ranks of their allies' armies. They would fight to

liberate their homelands, or to prevent infidels from seizing holy lands. Converted prisoners could also act as underground

agents, sent behind the Allied lines to stir up dissent, especially within minority nationalities. From a more long-term

perspective, the Germans planned to establish friendly relations with these prisoners so that when they returned home

after a German victory, they would serve German interests in the occupied territories.1

5

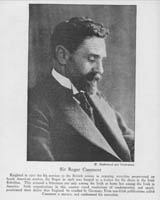

At Limburg, the Germans collected Irish POWs culled from the British ranks in camps across Germany. The Germans

assembled approximately two thousand Irish prisoners in the prison camp and encouraged them to join a special regiment in

the German Army. Sir Roger Casement, famous for his work exposing terrible conditions in the Upper Congo before the

war, was an ardent Irish nationalist and saw the war as an opportunity for Ireland to gain its independence.

At Limburg, the Germans collected Irish POWs culled from the British ranks in camps across Germany. The Germans

assembled approximately two thousand Irish prisoners in the prison camp and encouraged them to join a special regiment in

the German Army. Sir Roger Casement, famous for his work exposing terrible conditions in the Upper Congo before the

war, was an ardent Irish nationalist and saw the war as an opportunity for Ireland to gain its independence.

He traveled to Berlin in 1914 to secure German aid in obtaining Ireland's freedom. With the assistance of the Germans,

Casement conducted an extensive propaganda campaign and sought recruits for an uprising against the English in Ireland.

The Germans recruited only fifty-four POWs for Casement's cause, and trained them to become members of the Irish Brigade.

Casement was captured by the English at Tralee in April 1916, as he landed from a German submarine, and the British eventually

tried and executed Casement for treason. As a result of the failure of the Casement mission and the lack of response to Irish

nationalism, the Germans imposed rigid discipline and eliminated privileges for the POWs at Limburg. Most were transferred

to labor detachments, and many of Casement's most vocal critics ended up in punishment barracks.2

He traveled to Berlin in 1914 to secure German aid in obtaining Ireland's freedom. With the assistance of the Germans,

Casement conducted an extensive propaganda campaign and sought recruits for an uprising against the English in Ireland.

The Germans recruited only fifty-four POWs for Casement's cause, and trained them to become members of the Irish Brigade.

Casement was captured by the English at Tralee in April 1916, as he landed from a German submarine, and the British eventually

tried and executed Casement for treason. As a result of the failure of the Casement mission and the lack of response to Irish

nationalism, the Germans imposed rigid discipline and eliminated privileges for the POWs at Limburg. Most were transferred

to labor detachments, and many of Casement's most vocal critics ended up in punishment barracks.2

6

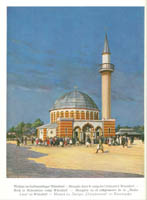

The Germans had much greater success recruiting Muslim Allied prisoners. The Germans captured Indian troops from

Muslim provinces and French colonial troops from North Africa and sent them to a propaganda camp at Zossen-Wünsdorf,

the Halbmondlager (Crescent Moon Prison). Ghurkas, Sikhs, Muslims, Shakurs, and North Africans were among the

approximately 3,400 POWs at this camp.

The Germans had much greater success recruiting Muslim Allied prisoners. The Germans captured Indian troops from

Muslim provinces and French colonial troops from North Africa and sent them to a propaganda camp at Zossen-Wünsdorf,

the Halbmondlager (Crescent Moon Prison). Ghurkas, Sikhs, Muslims, Shakurs, and North Africans were among the

approximately 3,400 POWs at this camp.

The Germans constructed a model camp for these prisoners, including comfortable quarters, special kitchens and foods,

and even a mosque (presented by the Kaiser). The Germans sent Russian Tartars, also Muslims, to the neighboring prison

camp at Zossen-Weinberge, which featured similarly comfortable accommodations.

The Germans constructed a model camp for these prisoners, including comfortable quarters, special kitchens and foods,

and even a mosque (presented by the Kaiser). The Germans sent Russian Tartars, also Muslims, to the neighboring prison

camp at Zossen-Weinberge, which featured similarly comfortable accommodations.

Before the war, Kaiser Wilhelm II had portrayed himself as a friend of Islam and supported the Turks' call for a

jihad (holy war) against the Allies. This marked the beginning of a campaign by the Germans to convert Muslim

prisoners to the Central Power cause. Prisoners received special rations, including food unavailable to German civilians,

such as rice and wheat flour. The Germans allowed Turkish officials to visit the camp to give patriotic speeches and

enlist prisoners for the Ottoman Army. U.S. Ambassador James W. Gerard estimated that about two thousand Allied POWs agreed to

join the Turkish legions and fight in Macedonia, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.3

Before the war, Kaiser Wilhelm II had portrayed himself as a friend of Islam and supported the Turks' call for a

jihad (holy war) against the Allies. This marked the beginning of a campaign by the Germans to convert Muslim

prisoners to the Central Power cause. Prisoners received special rations, including food unavailable to German civilians,

such as rice and wheat flour. The Germans allowed Turkish officials to visit the camp to give patriotic speeches and

enlist prisoners for the Ottoman Army. U.S. Ambassador James W. Gerard estimated that about two thousand Allied POWs agreed to

join the Turkish legions and fight in Macedonia, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.3

7

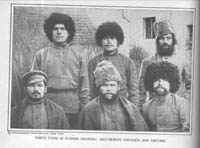

The German military concentrated national minority groups in other propaganda camps. The Germans assigned Flemish

prisoners to Göttingen, Ukrainian POWs to Rastatt and Hammerstein, and German-Russian prisoners to Hammerstein.

Other groups, including White Russian and German-Russian prisoners, were sent to other special prison camps.

The Germans hoped to indoctrinate these Flemish and Russian POWs through special literature and educational programs in

hopes of preparing them for positions of leadership in the special economic zones Germany planned to administer during and after

the war. To agitate class conflict and confusion behind Allied lines, the Germans sent Russians with revolutionary

tendencies back home with money and passports to stir up political problems for the Tsarist government.

The Germans hoped to indoctrinate these Flemish and Russian POWs through special literature and educational programs in

hopes of preparing them for positions of leadership in the special economic zones Germany planned to administer during and after

the war. To agitate class conflict and confusion behind Allied lines, the Germans sent Russians with revolutionary

tendencies back home with money and passports to stir up political problems for the Tsarist government.

The Gurkha, Sikh, and Shakur prisoners at Zossen-Wünsdorf received similar indoctrination. The Germans planned to

foment political instability in the British Empire after the war by instilling nationalist aspirations among the

Indian prisoners of war. Post-war politics played a crucial role in German POW policy.4

The Gurkha, Sikh, and Shakur prisoners at Zossen-Wünsdorf received similar indoctrination. The Germans planned to

foment political instability in the British Empire after the war by instilling nationalist aspirations among the

Indian prisoners of war. Post-war politics played a crucial role in German POW policy.4

8

In many ways, life in propaganda camps was far superior to that in other types of facilities, especially the physical

conditions. Association secretaries noted, however, that these men suffered from unique mental and moral pressures, as

German authorities tried to persuade them to renounce their oaths as Allied soldiers and desert to the enemy. While the

Germans showered these men with kindness, other Allied prisoners held them in a great deal of contempt. To alleviate the

situation, the YMCA sent field secretaries to the propaganda camps to set up Associations and help them through these moral

dilemmas. Conrad Hoffman and James Sprunger visited the propaganda camp at Limburg and worked with the Irish prisoners. For

the Indian POWs at Zossen, Hoffman arranged to have special food and spices, especially curry, supplied to remind them that

the Allies had not forgotten their sacrifices in prison. The Association program was also established for Flemish prisoners

at Göttingen, and Hoffman began similar services for Ukrainian POWs at Rastatt when he introduced Red Triangle work for

American prisoners early in 1918.5

In many ways, life in propaganda camps was far superior to that in other types of facilities, especially the physical

conditions. Association secretaries noted, however, that these men suffered from unique mental and moral pressures, as

German authorities tried to persuade them to renounce their oaths as Allied soldiers and desert to the enemy. While the

Germans showered these men with kindness, other Allied prisoners held them in a great deal of contempt. To alleviate the

situation, the YMCA sent field secretaries to the propaganda camps to set up Associations and help them through these moral

dilemmas. Conrad Hoffman and James Sprunger visited the propaganda camp at Limburg and worked with the Irish prisoners. For

the Indian POWs at Zossen, Hoffman arranged to have special food and spices, especially curry, supplied to remind them that

the Allies had not forgotten their sacrifices in prison. The Association program was also established for Flemish prisoners

at Göttingen, and Hoffman began similar services for Ukrainian POWs at Rastatt when he introduced Red Triangle work for

American prisoners early in 1918.5

Foreign Relief Programs

9

Because of the American YMCA's unique level of contact with Allied POWs, the Association worked in conjunction with

other welfare organizations from Allied countries. Madame Orjewsky of the Russian Sisters' Commission approached Hoffman

regarding joint welfare operations. The Russian Sisters' Commission acted in an official capacity for the Russian government

inspecting Russian POW conditions in German prison camps. Madame Orjewsky asked the American YMCA to take over Russian POW

needs permanently in Germany. The commission would provide goods required by Russian prisoners, and American YMCA secretaries

would distribute them. Hoffman pointed out that the key to this service was the establishment of a reciprocal system in

the Tsarist Empire-German relief organizations would forward supplies to Russia, where American YMCA secretaries would distribute the

goods to German POWs. The major obstacle to the scheme, from Hoffman's perspective, was the overall cost of the program.

WPA secretaries also worked with the Servian Relief Committee, based in Switzerland. The Red Triangle distributed clothing

to destitute Serbian POWs in German prison camps.6

Because of the American YMCA's unique level of contact with Allied POWs, the Association worked in conjunction with

other welfare organizations from Allied countries. Madame Orjewsky of the Russian Sisters' Commission approached Hoffman

regarding joint welfare operations. The Russian Sisters' Commission acted in an official capacity for the Russian government

inspecting Russian POW conditions in German prison camps. Madame Orjewsky asked the American YMCA to take over Russian POW

needs permanently in Germany. The commission would provide goods required by Russian prisoners, and American YMCA secretaries

would distribute them. Hoffman pointed out that the key to this service was the establishment of a reciprocal system in

the Tsarist Empire-German relief organizations would forward supplies to Russia, where American YMCA secretaries would distribute the

goods to German POWs. The major obstacle to the scheme, from Hoffman's perspective, was the overall cost of the program.

WPA secretaries also worked with the Servian Relief Committee, based in Switzerland. The Red Triangle distributed clothing

to destitute Serbian POWs in German prison camps.6

10

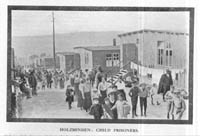

The American YMCA also expressed great concern for Belgian and Northern French refugees interned in German prison

camps. J. Spencer Kennard conducted visits to the civilian internment camp at Holzminden, where approximately

ten thousand Polish, Belgian, and French internees were imprisoned. Beautifully situated in the foothills of the Harz

Mountains, the facility was divided into two camps: one for men, and a second for five hundred women and children. During

the day, the German authorities permitted the women and children to enter the main compound, and their presence

resulted in a more cheerful atmosphere, but these internees were still depressed about their lot.

The American YMCA also expressed great concern for Belgian and Northern French refugees interned in German prison

camps. J. Spencer Kennard conducted visits to the civilian internment camp at Holzminden, where approximately

ten thousand Polish, Belgian, and French internees were imprisoned. Beautifully situated in the foothills of the Harz

Mountains, the facility was divided into two camps: one for men, and a second for five hundred women and children. During

the day, the German authorities permitted the women and children to enter the main compound, and their presence

resulted in a more cheerful atmosphere, but these internees were still depressed about their lot.

They included peasants, clerks, students, and city officials, thrust together to share a common plight. Kennard

established a fund for the relief of the needy Belgians at Holzminden. He acknowledged that, while a similar fund

for French internees would be helpful, it was not necessary due to the support provided by French welfare agencies.

Kennard used what money he had to obtain food for these unfortunates to try to keep them in good health. He also

noted that some Russian internees at Holzminden needed more food and had the money to pay for additional nourishment.

The food situation in Germany was growing ever more critical by January 1917, and he feared for the future of the

Allied internees.7

They included peasants, clerks, students, and city officials, thrust together to share a common plight. Kennard

established a fund for the relief of the needy Belgians at Holzminden. He acknowledged that, while a similar fund

for French internees would be helpful, it was not necessary due to the support provided by French welfare agencies.

Kennard used what money he had to obtain food for these unfortunates to try to keep them in good health. He also

noted that some Russian internees at Holzminden needed more food and had the money to pay for additional nourishment.

The food situation in Germany was growing ever more critical by January 1917, and he feared for the future of the

Allied internees.7

11 The American YMCA also worked in close association with German POW relief organizations to improve conditions for Central Power prisoners in Russia. The German public was very concerned about the dismal conditions reported in the East and supported efforts to improve the lot of prisoners. Countess Pourtales, the representative of Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden and wife of the former German ambassador to Russia, was the president of the Fraudienst der Deutschen Kriegsgefangenen-Hilfe (Ladies' Aid Society for German Prisoners of War). This POW relief organization worked closely with the Unterkuftsabsteilung (Accommodations Section) of the Ministry of War to obtain warm clothing and food for German POWs in European Russia and Siberia. The countess made arrangements with Hoffman for the American YMCA to provide winter clothing to German prisoners in prison camps not directly served by the U.S. embassy. This allowed American YMCA secretaries even greater access to Central Power POWs in Russia.8

12 Nor were POWs and internees the only target group for American YMCA assistance. A large number of Russian refugees were trapped in Berlin at the beginning of the war. The German police closely monitored the activities of these enemy aliens, and their opportunities for gainful employment were limited. As a result, most Russian refugees survived on the funds sent to them by their families in Russia via neutral countries. This support was sometimes tenuous, and it ended completely when Bolshevik authorities cut off these transmissions in 1917 after the October Revolution. Because these Russian civilian refugees often faced a bleak existence, the American YMCA organized the Russian Relief Committee in October 1916. Over the next twelve months, the Association distributed 44,800 Marks to over one hundred families on a monthly basis. This service undoubtedly saved many Russian refugees from want and starvation.9

American YMCA Relief Work in Labor Detachments

13

Under the Hague Agreements of 1899 and 1907, enlisted POWs were required to work upon demand by the incarcerating

power. Refusal to work was considered insubordination, and prisoners became subject to military discipline.

Non-commissioned officers could volunteer for labor details if they desired, but they were not required to work.

Officers were specifically exempted from labor assignments under the 1907 agreement. Captor governments could

either employ POWs directly or contract prisoner labor out to private firms or individuals. Prisoners enjoyed

certain rights under the Hague Agreements. POWs could not be forced to work in areas of "military operations,"

a vaguely defined term which required captor nations to move POWs from combat areas as quickly as possible.

Prisoners were also exempt from working in war-related industries, such as munitions factories. In return for

their labor, prisoners were to receive wages commensurate with the skill level of the job.10

Under the Hague Agreements of 1899 and 1907, enlisted POWs were required to work upon demand by the incarcerating

power. Refusal to work was considered insubordination, and prisoners became subject to military discipline.

Non-commissioned officers could volunteer for labor details if they desired, but they were not required to work.

Officers were specifically exempted from labor assignments under the 1907 agreement. Captor governments could

either employ POWs directly or contract prisoner labor out to private firms or individuals. Prisoners enjoyed

certain rights under the Hague Agreements. POWs could not be forced to work in areas of "military operations,"

a vaguely defined term which required captor nations to move POWs from combat areas as quickly as possible.

Prisoners were also exempt from working in war-related industries, such as munitions factories. In return for

their labor, prisoners were to receive wages commensurate with the skill level of the job.10

14

When the war first began, the Germans were preoccupied with finding proper facilities for the large numbers of

POWs they had captured in Belgium, northern France, and East Prussia. The Ministry of War had not given much thought

to the employment of prisoners until the war was well underway. By 1915, only a few prisoners had been assigned to work projects,

most to small-scale operations. However, supporting a large idle population in a country that was becoming labor-scarce

due to military mobilization imposed a tremendous burden on the imperial economy.

When the war first began, the Germans were preoccupied with finding proper facilities for the large numbers of

POWs they had captured in Belgium, northern France, and East Prussia. The Ministry of War had not given much thought

to the employment of prisoners until the war was well underway. By 1915, only a few prisoners had been assigned to work projects,

most to small-scale operations. However, supporting a large idle population in a country that was becoming labor-scarce

due to military mobilization imposed a tremendous burden on the imperial economy.

As a result, the Ministry of War decided to put POWs to work in a variety of industries. By December 1916, the Germans

employed 1.1 million military and civilian internees, with 340,000 working in industry and trade, and 630,000 in

agriculture. This accounted for 61 percent of all the POWs held by the Germans at that time-a number that is even

more significant than it appears, since a large percentage of prisoners were wounded, or officers and could not work,

while non-commissioned officers were not required to work. From that point forward, the Germans utilized their POW

population as efficiently as possible to replace male workers who had been drafted into the German armed

forces.11

As a result, the Ministry of War decided to put POWs to work in a variety of industries. By December 1916, the Germans

employed 1.1 million military and civilian internees, with 340,000 working in industry and trade, and 630,000 in

agriculture. This accounted for 61 percent of all the POWs held by the Germans at that time-a number that is even

more significant than it appears, since a large percentage of prisoners were wounded, or officers and could not work,

while non-commissioned officers were not required to work. From that point forward, the Germans utilized their POW

population as efficiently as possible to replace male workers who had been drafted into the German armed

forces.11

15

The Germans employed Allied POWs in a wide variety of occupations. Prisoners were sent to main prison camps,

or Stammlager, and then assigned to Arbeitskommandos (labor detachments) for work in industry or

agriculture. These detachments ranged from ten to two thousand men, and they usually lived near the place of

their employment. Prisoners worked in large-scale government projects such as railroad, road, and bridge construction,

or moorland reclamation.

The Germans employed Allied POWs in a wide variety of occupations. Prisoners were sent to main prison camps,

or Stammlager, and then assigned to Arbeitskommandos (labor detachments) for work in industry or

agriculture. These detachments ranged from ten to two thousand men, and they usually lived near the place of

their employment. Prisoners worked in large-scale government projects such as railroad, road, and bridge construction,

or moorland reclamation.

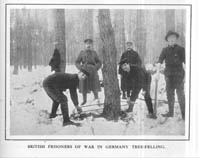

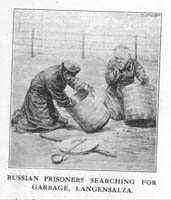

Large industrial employers also contracted out for POW labor for work in steel factories, quarries, and coal mines.

Smaller employers utilized prisoners as foresters, stevedores, and garbage men. Prisoners had the opportunity to

work, usually in small groups, in agricultural pursuits as farmhands.

Large industrial employers also contracted out for POW labor for work in steel factories, quarries, and coal mines.

Smaller employers utilized prisoners as foresters, stevedores, and garbage men. Prisoners had the opportunity to

work, usually in small groups, in agricultural pursuits as farmhands.

A special category of prisoners worked in the Etappengebiet (War Zone), building roads and railway lines

or even digging trenches. While this was a violation in spirit of the Hague Agreements, the Allies followed the

same practice with their POW labor. Prisoners assigned to this work came from the parent camps at Friedrichsfeld,

Limburg, and Wahn. Normally, American YMCA secretaries were not permitted to visit these camps, but Hoffman managed to

gain entry on an occasional basis.12

A special category of prisoners worked in the Etappengebiet (War Zone), building roads and railway lines

or even digging trenches. While this was a violation in spirit of the Hague Agreements, the Allies followed the

same practice with their POW labor. Prisoners assigned to this work came from the parent camps at Friedrichsfeld,

Limburg, and Wahn. Normally, American YMCA secretaries were not permitted to visit these camps, but Hoffman managed to

gain entry on an occasional basis.12

16

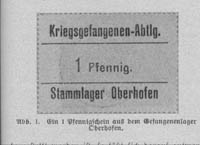

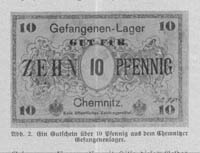

Prisoners' wages were determined by skill level and by contract between private employers and Army Corps commands.

To hinder escapes, POWs were paid in script (Lagergeld), which could only be used to make purchases at the prison

camp stores or credited in prison bank accounts.

Prisoners' wages were determined by skill level and by contract between private employers and Army Corps commands.

To hinder escapes, POWs were paid in script (Lagergeld), which could only be used to make purchases at the prison

camp stores or credited in prison bank accounts.

The Germans did not want POWs to hold large amounts of money, which they could use to bribe guards or to help them

escape to neutral countries. Farm labor was the least profitable of trades; POWs received sixteen to thirty-five Pfennige a

day (in 1917, one Mark was worth seventeen cents).

The Germans did not want POWs to hold large amounts of money, which they could use to bribe guards or to help them

escape to neutral countries. Farm labor was the least profitable of trades; POWs received sixteen to thirty-five Pfennige a

day (in 1917, one Mark was worth seventeen cents).

Small industrial employers paid a bit more, from thirty to fifty Pfennige daily. Prisoners working for large industries

earned from seventy-five Pfennige to one Mark per day. Highly skilled and professional prisoners could earn as much as two

to three Marks daily.13

Small industrial employers paid a bit more, from thirty to fifty Pfennige daily. Prisoners working for large industries

earned from seventy-five Pfennige to one Mark per day. Highly skilled and professional prisoners could earn as much as two

to three Marks daily.13

17

Employing POWs offered many advantages for both the German military and Allied prisoners. For the Germans, the

employment of war prisoners provided a new source of labor for vital industries and helped ease the burden of having

to feed, clothe, and shelter a large force of unproductive men. While POWs were not as efficient as German workers

(prisoners did not have the same motivation as nationals, and efficiency estimates placed POW labor at 50 percent in

industrial labor and 75 percent in agricultural pursuits), these men were skilled in a large number of trades. For

Allied prisoners, the bonuses were far greater. They could escape the monotony of life behind barbed-wire fences.

Employing POWs offered many advantages for both the German military and Allied prisoners. For the Germans, the

employment of war prisoners provided a new source of labor for vital industries and helped ease the burden of having

to feed, clothe, and shelter a large force of unproductive men. While POWs were not as efficient as German workers

(prisoners did not have the same motivation as nationals, and efficiency estimates placed POW labor at 50 percent in

industrial labor and 75 percent in agricultural pursuits), these men were skilled in a large number of trades. For

Allied prisoners, the bonuses were far greater. They could escape the monotony of life behind barbed-wire fences.

Many POWs welcomed the opportunity to work simply for the change of scenery. Work provided prisoners with a steady

income, which they could use to supplement their diets, and a more normal social environment than prison life.

Allied prisoners and German civilians also got the opportunity to "see the face of the enemy" by working and living

together, which promoted a better understanding between belligerents. Not only did POWs and German workers interact

in the workplace, but many prisoners, especially on farms, also lived in close proximity with their employers. Eating

at the same table and sleeping in the same house reduced misunderstandings between Germans and Allied prisoners. Most

importantly, workers gained access to better food rations in Arbeitskommandos than in the prisons. The Germans

wanted healthy laborers, so that they could get as much work out of prisoners as possible. POWs on agricultural

assignments had access to far better rations than urban German civilians. Many Russian, Serbian, and Romanian POWs

survived the war because they were able to secure jobs on farms.14

Many POWs welcomed the opportunity to work simply for the change of scenery. Work provided prisoners with a steady

income, which they could use to supplement their diets, and a more normal social environment than prison life.

Allied prisoners and German civilians also got the opportunity to "see the face of the enemy" by working and living

together, which promoted a better understanding between belligerents. Not only did POWs and German workers interact

in the workplace, but many prisoners, especially on farms, also lived in close proximity with their employers. Eating

at the same table and sleeping in the same house reduced misunderstandings between Germans and Allied prisoners. Most

importantly, workers gained access to better food rations in Arbeitskommandos than in the prisons. The Germans

wanted healthy laborers, so that they could get as much work out of prisoners as possible. POWs on agricultural

assignments had access to far better rations than urban German civilians. Many Russian, Serbian, and Romanian POWs

survived the war because they were able to secure jobs on farms.14

18

Problems also accompanied the transfer of POWs from prison camps to Arbeitskommandos. As mentioned earlier,

some prisoners had to work in the Etappensgebiet under dangerous conditions. Prisoners also had to work long, hard

hours, especially if they were employed in coal mines or quarries.

Problems also accompanied the transfer of POWs from prison camps to Arbeitskommandos. As mentioned earlier,

some prisoners had to work in the Etappensgebiet under dangerous conditions. Prisoners also had to work long, hard

hours, especially if they were employed in coal mines or quarries.

POWs complained about inadequate housing arrangements, especially in cases where prison labor had just been introduced

at a factory (security remained a top priority). Some were also dissatisfied with the quality of rations, despite the Germans' incentive to house

and feed prisoners well in order to maximize productivity.

POWs complained about inadequate housing arrangements, especially in cases where prison labor had just been introduced

at a factory (security remained a top priority). Some were also dissatisfied with the quality of rations, despite the Germans' incentive to house

and feed prisoners well in order to maximize productivity.

Relations with German workers were not always harmonious. Some German foremen abused prisoners, and fights between

POWs and German workers occurred from time to time. Strikes by prisoners were harshly punished as insubordination

by German authorities. Prisoners were also vulnerable to social vices that did not exist in prison, such as ready

access to German women. But, for the most part, the benefits of getting POWs out of the prison camps and

working outweighed these problems.15

Relations with German workers were not always harmonious. Some German foremen abused prisoners, and fights between

POWs and German workers occurred from time to time. Strikes by prisoners were harshly punished as insubordination

by German authorities. Prisoners were also vulnerable to social vices that did not exist in prison, such as ready

access to German women. But, for the most part, the benefits of getting POWs out of the prison camps and

working outweighed these problems.15

19

The German Ministry of War's decision to assign the bulk of Allied prisoners in their custody to labor detachments

had a serious impact on field secretary POW relief work. While the Red Triangle workers realized that working would

ease the food shortage and monotony of prison camp for POWs, the scattering of prisoners across Germany made the

development and expansion of WPA work far more difficult. Earlier in the war, WPA field secretaries could visit the

major prison camps and come into contact with the preponderance of Allied prisoners in Germany. The disbursement of

POWs in large and small labor detachments undermined this contact.

The German Ministry of War's decision to assign the bulk of Allied prisoners in their custody to labor detachments

had a serious impact on field secretary POW relief work. While the Red Triangle workers realized that working would

ease the food shortage and monotony of prison camp for POWs, the scattering of prisoners across Germany made the

development and expansion of WPA work far more difficult. Earlier in the war, WPA field secretaries could visit the

major prison camps and come into contact with the preponderance of Allied prisoners in Germany. The disbursement of

POWs in large and small labor detachments undermined this contact.

Kennard found that POWs from the Stammlager at Soltau in Prussia had been sent to fifty different branch labor

camps. Although Soltau was one of the largest prison camps in Germany, with over seventy-five thousand inmates, all but ten thousand had

been sent away on work details. The American secretary lamented that one secretary now had to cover an area that

represented enough work for four or five secretaries. More importantly, the Germans were determined to employ as

many prisoners as possible in the German war effort. They implemented a general plan to make all able-bodied prisoners

choose to leave prison camps. By February 1917, Ambassador Gerard estimated that 85 percent of Allied POWs in Germany

were serving in work parties.

Kennard found that POWs from the Stammlager at Soltau in Prussia had been sent to fifty different branch labor

camps. Although Soltau was one of the largest prison camps in Germany, with over seventy-five thousand inmates, all but ten thousand had

been sent away on work details. The American secretary lamented that one secretary now had to cover an area that

represented enough work for four or five secretaries. More importantly, the Germans were determined to employ as

many prisoners as possible in the German war effort. They implemented a general plan to make all able-bodied prisoners

choose to leave prison camps. By February 1917, Ambassador Gerard estimated that 85 percent of Allied POWs in Germany

were serving in work parties.

In line with this policy, German military authorities prohibited most amusements in prison camps, including many aspects

of the Association program. The objective was not to punish prisoners, but to make them prefer work details to prison

camps. As a result, most camps had only 5 to 15 percent of their normal populations inside the compounds during the day.

Those who remained were the sick, the permanently disabled, those incarcerated for criminal acts, sergeants, adjutants,

civilians, POW Association board members, and clerical workers. A large majority of these men were in the hospital or

stockade. Many WPA field secretaries found that organized school attendance dropped off sharply, and many Association

activities disappeared altogether. The YMCA secretaries had to develop new tools and programs to meet the demands of

this situation.16

In line with this policy, German military authorities prohibited most amusements in prison camps, including many aspects

of the Association program. The objective was not to punish prisoners, but to make them prefer work details to prison

camps. As a result, most camps had only 5 to 15 percent of their normal populations inside the compounds during the day.

Those who remained were the sick, the permanently disabled, those incarcerated for criminal acts, sergeants, adjutants,

civilians, POW Association board members, and clerical workers. A large majority of these men were in the hospital or

stockade. Many WPA field secretaries found that organized school attendance dropped off sharply, and many Association

activities disappeared altogether. The YMCA secretaries had to develop new tools and programs to meet the demands of

this situation.16

20

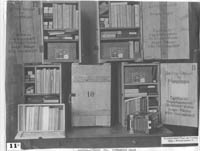

The Association responded by increasing correspondence service and field visitations. Prisoners could write to

the WPA Office in Berlin and request books, musical instruments, athletic equipment, and religious material. The

YMCA organized circulating libraries-different collections of twenty-five to thirty books housed in specially

constructed boxes-and sent the books to the main camps.

The Association responded by increasing correspondence service and field visitations. Prisoners could write to

the WPA Office in Berlin and request books, musical instruments, athletic equipment, and religious material. The

YMCA organized circulating libraries-different collections of twenty-five to thirty books housed in specially

constructed boxes-and sent the books to the main camps.

Members of the Association committee then sent these libraries to the larger branch work parties. When all the

books had been read, the labor detachment could send the library back in exchange for a new set of books. Hoffman

established a similar system with record collections. The WPA Office in Berlin would send a gramophone and a set of

twenty records to labor detachments via the main prison camps. When the prisoners tired of hearing these records,

they could exchange their set for a new collection.

Members of the Association committee then sent these libraries to the larger branch work parties. When all the

books had been read, the labor detachment could send the library back in exchange for a new set of books. Hoffman

established a similar system with record collections. The WPA Office in Berlin would send a gramophone and a set of

twenty records to labor detachments via the main prison camps. When the prisoners tired of hearing these records,

they could exchange their set for a new collection.

The Senior Secretary also sent school supplies and lantern slides to working prisoners. For the Christmas holidays,

the Association sent entertainment boxes to work parties, which included reading material, assorted games, and a

few musical instruments to help them pass their leisure time.

The Senior Secretary also sent school supplies and lantern slides to working prisoners. For the Christmas holidays,

the Association sent entertainment boxes to work parties, which included reading material, assorted games, and a

few musical instruments to help them pass their leisure time.

Most importantly, despite the difficulties in transportation and the reduction in contact, WPA field secretaries

made every effort to visit POWs working in factories and fields to maintain the personal contact that was the

hallmark of their service. The value of Association secretaries in prisoner morale work persuaded the German military

and employers to encourage such visits whenever possible. In his reports regarding visits to Arbeitskommandos,

Carl T. Michel described his morale work. He provided small musical instruments, looked at the prisoners' pictures,

and sang with them. The American secretary also encouraged them to go to church and to obey their guards. He believed

the personal touch was of the greatest value in helping to buoy prisoners' spirits.17

Most importantly, despite the difficulties in transportation and the reduction in contact, WPA field secretaries

made every effort to visit POWs working in factories and fields to maintain the personal contact that was the

hallmark of their service. The value of Association secretaries in prisoner morale work persuaded the German military

and employers to encourage such visits whenever possible. In his reports regarding visits to Arbeitskommandos,

Carl T. Michel described his morale work. He provided small musical instruments, looked at the prisoners' pictures,

and sang with them. The American secretary also encouraged them to go to church and to obey their guards. He believed

the personal touch was of the greatest value in helping to buoy prisoners' spirits.17

The American YMCA and the Lesser German Kingdoms

21 Not only did Archibald Harte have to negotiate with the Prussian Ministry of War to gain access to Allied POWs in Germany, but similar arrangements also had to be concluded with the Ministries of War in Saxony, Bavaria, and Württemberg. These kingdoms operated semi-independently from Berlin and jealously protected their autonomy. The Saxons controlled two army corps districts (the I Royal Saxon, or XII Army Corps, in Dresden; and the II Royal Saxon, or XIX Army Corps, in Leipzig), while the Württembergers supervised one Bezirk (district) (the Royal Württemberg, or XIII Army Corps, in Stuttgart). The Bavarians held even greater independence than the other kingdoms, controlling the I Royal Bavarian Army Corps (Munich), the II Royal Bavarian Army Corps (Würzburg), and the III Royal Bavarian Army Corps (Nürnberg) regions. For American WPA field secretaries to visit Allied POWs in these regions, the YMCA had to gain access from each province's military leadership.18

22

E. O. Jacob was the American WPA secretary assigned to Saxony, and he established the Association program for

Allied POWs there. The YMCA was a well-known and accepted social welfare organization in this Protestant kingdom.

Jacob established an extensive WPA program across Saxony. He built two YMCA halls in the kingdom, and gained access

to barracks in other camps. The development of Association schools, ranging from primary education for illiterate

Russians and Serbs to university extension programs offered through the University of Dresden, was a high priority

for Jacob.

E. O. Jacob was the American WPA secretary assigned to Saxony, and he established the Association program for

Allied POWs there. The YMCA was a well-known and accepted social welfare organization in this Protestant kingdom.

Jacob established an extensive WPA program across Saxony. He built two YMCA halls in the kingdom, and gained access

to barracks in other camps. The development of Association schools, ranging from primary education for illiterate

Russians and Serbs to university extension programs offered through the University of Dresden, was a high priority

for Jacob.

As part of this effort, Jacob established and expanded camp libraries and introduced book-binding departments to

keep books in circulation. He also promoted industrial and handicraft work in Saxon prison camps, including tailoring,

shoemaking, toy-making, and needlework. Some of these products were sold in Scandinavia as part of Crown Princess

Margaret's POW bazaar program. Physical education was not neglected, as he provided volleyball, basketball, soccer,

ice skates, and baseball equipment. Jacob also provided motion picture shows and encouraged entertainment programs

by providing music and instruments for bands, orchestras, choruses, and literary and dramatic societies.19

As part of this effort, Jacob established and expanded camp libraries and introduced book-binding departments to

keep books in circulation. He also promoted industrial and handicraft work in Saxon prison camps, including tailoring,

shoemaking, toy-making, and needlework. Some of these products were sold in Scandinavia as part of Crown Princess

Margaret's POW bazaar program. Physical education was not neglected, as he provided volleyball, basketball, soccer,

ice skates, and baseball equipment. Jacob also provided motion picture shows and encouraged entertainment programs

by providing music and instruments for bands, orchestras, choruses, and literary and dramatic societies.19

23

The American secretary placed a high priority on religious work in Saxony, but he faced a serious problem: of the fifty thousand

POWs in the kingdom, only two hundred were Protestants, and the ban against proselytizing restricted his religious work. Jacob,

however, always worked with French Catholic and Russian Orthodox priests.

The American secretary placed a high priority on religious work in Saxony, but he faced a serious problem: of the fifty thousand

POWs in the kingdom, only two hundred were Protestants, and the ban against proselytizing restricted his religious work. Jacob,

however, always worked with French Catholic and Russian Orthodox priests.

He provided icons, altar decorations, incense, sacred pictures, white flour for holy bread, New Testaments, Old

Testaments, prayer books, and Jewish religious paraphernalia. Jacob also worked to help POWs through the Christmas

season. In December 1916, Jacob sent Christmas cards to British, French, Serbian, Russian, and Belgian POWs, as well

as to their German guards. He also dispatched two hundred parcels of games, musical instruments, and Christmas tree candles

to POW barracks, hospital wards, and working parties. In camps that did could not afford to purchase Christmas trees, he made sure

that the POWs obtained large trees and decorations.

He provided icons, altar decorations, incense, sacred pictures, white flour for holy bread, New Testaments, Old

Testaments, prayer books, and Jewish religious paraphernalia. Jacob also worked to help POWs through the Christmas

season. In December 1916, Jacob sent Christmas cards to British, French, Serbian, Russian, and Belgian POWs, as well

as to their German guards. He also dispatched two hundred parcels of games, musical instruments, and Christmas tree candles

to POW barracks, hospital wards, and working parties. In camps that did could not afford to purchase Christmas trees, he made sure

that the POWs obtained large trees and decorations.

He sought to spread the "real Christmas spirit," and recommended that the Association multiply its yuletide efforts

for the next holiday season. Most importantly, Jacob recognized that physical relief was becoming increasingly critical.

While British, French, and Belgian prisoners received food parcels to supplement their rations, he feared that many

Russian and Serbian POWs would not survive the war. He strove to find clothing and food for these men. Jacob had food

parcels sent from the WPA Office in Copenhagen for the neediest Serbian and Russian prisoners. The POW situation was

similar in the Protestant kingdom of Württemberg, and the Ministry of War in Stuttgart permitted the YMCA to set

up programs for Allied prisoners under its jurisdiction.20

He sought to spread the "real Christmas spirit," and recommended that the Association multiply its yuletide efforts

for the next holiday season. Most importantly, Jacob recognized that physical relief was becoming increasingly critical.

While British, French, and Belgian prisoners received food parcels to supplement their rations, he feared that many

Russian and Serbian POWs would not survive the war. He strove to find clothing and food for these men. Jacob had food

parcels sent from the WPA Office in Copenhagen for the neediest Serbian and Russian prisoners. The POW situation was

similar in the Protestant kingdom of Württemberg, and the Ministry of War in Stuttgart permitted the YMCA to set

up programs for Allied prisoners under its jurisdiction.20

24

WPA service in Roman Catholic Bavaria was more of a challenge. In October 1916, Hoffman received permission from the

Ministry of War in Munich to conduct an extensive survey of prison camps across the kingdom. With the support of the

Prussian Ministry of War, "which urgently commended the wish," Hoffman described the services the Association would

offer Allied prisoners under Bavarian care, and how reciprocal care would aid Bavarian prisoners held by the Allies.

WPA service in Roman Catholic Bavaria was more of a challenge. In October 1916, Hoffman received permission from the

Ministry of War in Munich to conduct an extensive survey of prison camps across the kingdom. With the support of the

Prussian Ministry of War, "which urgently commended the wish," Hoffman described the services the Association would

offer Allied prisoners under Bavarian care, and how reciprocal care would aid Bavarian prisoners held by the Allies.

He succeeded, and the Bavarians permitted the establishment of WPA operations to serve prisoners under their control.

Hoffman assigned Alfred Lowry, Jr. to take over as WPA field secretary in Bavaria. Lowry concentrated on Traunstein, a

civilian internment camp with a large Serbian population, and Lechfeld. Armed with funds provided by American friends,

the American secretary visited POWs and distributed two Marks apiece to needy prisoners, especially those who were unable

to work.

He succeeded, and the Bavarians permitted the establishment of WPA operations to serve prisoners under their control.

Hoffman assigned Alfred Lowry, Jr. to take over as WPA field secretary in Bavaria. Lowry concentrated on Traunstein, a

civilian internment camp with a large Serbian population, and Lechfeld. Armed with funds provided by American friends,

the American secretary visited POWs and distributed two Marks apiece to needy prisoners, especially those who were unable

to work.

As in the rest of Germany, Lowry found a wide range of conditions among the Allied POWs in Bavaria in terms of the

support they received from home. The French prisoners were in excellent shape (although the secretary noted that they

also had the most desires and requests), while Russian POWs ranged from fair to poor condition. The Serbian prisoners

were in the worst shape by far. Lowry set up a special fund for the welfare of Serbian prisoners, but these men were in

real distress, and "a game of checkers or a mouth organ affords but scant comfort."21

As in the rest of Germany, Lowry found a wide range of conditions among the Allied POWs in Bavaria in terms of the

support they received from home. The French prisoners were in excellent shape (although the secretary noted that they

also had the most desires and requests), while Russian POWs ranged from fair to poor condition. The Serbian prisoners

were in the worst shape by far. Lowry set up a special fund for the welfare of Serbian prisoners, but these men were in

real distress, and "a game of checkers or a mouth organ affords but scant comfort."21

25 Like secretaries in other parts of Germany, Lowry had to address the issue of prisoners assigned to labor detachments scattered across the kingdom. Large numbers of Allied POWs ended up working on farms, detailed in groups as small as one to three prisoners. As a result, Lowry set up an extensive correspondence program. He sent everything from soccer balls to blackboards to labor detachments and main prison camps, including textbooks, games (chess, checkers, dominoes, and lotto), orchestra music, mouth organs, and anatomical charts for a class of Russian students. Despite all of his efforts, he reported that he had unfilled requests for playing cards, wigs for plays, and decorations for the interior of a Catholic chapel. Conditions in Bavaria were the same as the rest of Germany.22

26

By February 1917, the American YMCA had an extensive WPA system in place across Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Association

had opened Central Power prison camps to WPA field secretaries, and these men had established a broad range of welfare services

for Allied prisoners. The YMCA overcame the problems associated with labor detachments, conducting operations in the lesser

German kingdoms, and even extending Association programs to POWs in propaganda camps. The one area where success eluded the

Association was in the establishment of a food supply distribution system. The YMCA's WPA organization came to a grinding halt

in February 1917 when the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany. The future of the POW relief program looked

bleak as the Association had to decide whether or not to pull American secretaries out of service in Central Europe.

By February 1917, the American YMCA had an extensive WPA system in place across Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Association

had opened Central Power prison camps to WPA field secretaries, and these men had established a broad range of welfare services

for Allied prisoners. The YMCA overcame the problems associated with labor detachments, conducting operations in the lesser

German kingdoms, and even extending Association programs to POWs in propaganda camps. The one area where success eluded the

Association was in the establishment of a food supply distribution system. The YMCA's WPA organization came to a grinding halt

in February 1917 when the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany. The future of the POW relief program looked

bleak as the Association had to decide whether or not to pull American secretaries out of service in Central Europe.

Notes:

Note 1: William Howard Taft, Frederick Harris, Frederic Houston Kent, and William J. Newlin, eds., Service with Fighting Men: An Account of the Work of the American Young Men's Christian Association in the World War, 2 vols. (New York: Association Press, 1922), 2:290-93. back

Note 2: The German Army hoped to recruit a considerable number of volunteers for the Irish Brigade to help foment revolution in the Emerald Isle. Ideally, these troops would support an effective uprising against British rule and would force the English to maintain a large garrison force on the island, which would drain resources from the Western Front. The Germans trained, drilled, and equipped the small number of Irish volunteers and issued them their own uniform. After the failure of the Easter Rebellion in April 1916, the Germans considered deploying the Irish Brigade on the Suez Front with the Turkish Army. Only one member of the brigade ever landed on Irish soil during the war. Lance Corporal Dowling was captured in April 1918 on the beach at County Clare after delivery by a U-boot. Conrad Hoffman, Jr., In the Prison Camps of Germany: A Narrative of "Y" Service among Prisoners of War (New York: Association Press, 1920), 81; James W. Gerard, My Four Years in Germany (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1917), 191; Gerard, My First Eighty-Three Years in America: The Memoirs of James W. Gerard (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1951), 211-12; Gerard, Face to Face with Kaiserism (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918), 80, 96, and 105; Daniel J. McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany: The Care and Treatment of the Prison of War with a History of the Development of the Principle of Neutral Inspection and Control (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1918), 121-25; To Make Men Traitors: Germany's Attempts to Seduce Her Prisoners-of-War (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1918); and "A German Plot." The "Manchester Guardian" History of the War, Volume 8: 1917-1919 (Manchester and London: John Heywood, Ltd., 1919):262-264. back

Note 3: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 81-83; Gerard, Face to Face with Kaiserism, 96 and 345; and McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, 130-34. back

Note 4: Of course, the most famous of Russian revolutionaries that the Germans employed to undermine the Tsarist government was Nikolai Lenin. The Germans transported the Bolshevik leader from Switzerland to Petrograd via a sealed train, which marked the beginning of the October Revolution. The Germans found no shortage of Russian revolutionaries among the POWs under their care, and Bolshevik propaganda became a critical concern with the approach of the Armistice and the immediate post-war period. Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 81-83 and 121; Taft, Harris, Kent, and Newlin, Service with Fighting Men, 2:290; Gerard, Face to Face with Kaiserism, 64-65, 96, and 345; McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in German, 130-34; and Oleh S. Fedyshen, Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution, 1917-1918 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1971), 37-47, 90-91, and 122-27. back

Note 5: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 37-41 and 81-83; Conrad Hoffman, "Prisoners of War in Germany: Letters from Conrad Hoffman," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 January 1916): 36-38; "Reading Room of the Association in the Prisoners-of-War Camp at Göttingen," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (6 December 1915): 10B; James W. Gerard, "The Association in Prisoners of War Camps: Observations of Its Work Given by Hon. James W. Gerard, Ex-Ambassador to Germany before the West Side New York Association," Association Men 42 (May 1917): 438; Conrad Hoffman, "Getting the News in Prison Camps," Association Men 44 (January 1919): 397; Lee Shipley, "It Kept Us from Going Mad," Association Men 44 (March 1919): 520 and 566; and McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, 132-33. back

Note 6: Conrad Hoffman, "Prisoners of War in Germany: Letters from Conrad Hoffman," 39; and E. O. Jacob, "Report of E. O. Jacob: For the Year Ending September 30, 1917," 30 September 1917, 4-5. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box 673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN. back

Note 7: J.S. Kennard, "Needs of Civilian Prisoners," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 February 1917): 47-48. back

Note 8: Conrad Hoffman, "Enlarged Opportunities for Service," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 November 1916): 41. back

Note 9: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 89-90; and Olin D. Wannamaker, For the Six Million Prisoners: The Welfare Work of the YMCA in the Prison Camps of Ten Nations during World War I (September 1921), 89. back

Note 10: McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, 228-251; and Review of Review Editors, Two Thousand Questions and Answers About the War: A Catechism of the Methods of Fighting, Travelling and Living; of the Armies, Navies and Air Fleets; of the Personalities, Politics and Geography of the Warring Countries (New York: The Review of Reviews Company, 1918), 118. back

Note 11: Richard B. Speed, III, Prisoners, Diplomats, and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1990), 77. back

Note 12: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 64; Review of Review Editors, Two Thousand Questions and Answers About the War, 118; and Speed, Prisoners, Diplomats, and the Great War, 77. back

Note 13: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 64; Review of Review Editors, Two Thousand Questions and Answers About the War, 118; and Speed, Prisoners, Diplomats, and the Great War, 77-78. back

Note 14: Alfred Lowry, Jr., "Needs of Prisoners in Bavaria," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 47; E. O. Jacob, "Working Parties Change Conditions," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 50; Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 64 and 73; Review of Review Editors, Two Thousand Questions and Answers About the War, 118; and Speed, Prisoners, Diplomats, and the Great War, 77. back

Note 15: James W. Gerard, "Give Us Bread," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 50; McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, 136-68; and Robert Jackson, The Prisoners 1914-1918 (London: Routledge, 1989), 77-82. back

Note 16: Carl T. Michel, "Extracts from Letters of Three of the New Secretaries," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 July 1916): 45; J. S. Kennard, "Needs of Civilian Prisoners," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 February 1917): 47-48; Alfred Lowry, Jr., "Needs of Prisoners in Bavaria," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 48; E. O. Jacob, "Working Parties Change Conditions," 49-50; James W. Gerard, "Give Us Bread," 50; and Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 126. back

Note 17: Carl T. Michel, "Extracts from Letters of Three of the New Secretaries," 45; Louis Wolferz, "Germany: For Prisoners of War," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 41-42; Conrad Hoffman, "Good Will of Outside Friends Finds Expression," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 June 1917): 44; E. O. Jacob, "Working Parties Change Conditions," 49-50; James W. Gerard, "Give Us Bread," 50; Conrad Hoffman, "Prisoners," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (10 June 1918): 47; Executive of the World's Committee of Y.M.C.A.'s, "World's Committee of Young Men's Christian Associations, Plenary Meeting of 1920 at Geneva: Report of the Executive for the Period July 1914 to June 1920," The Sphere 2:3 (1921): 197-98; J. Gustav White, "Prisoners-of-War at School: 'Next to Bread, We Need Books,' Say Prisoners-of-War Who Want to Go to School, Make Toys, and Learn Trades," Association Men 43 (September 1917): 16; "Extract from Letters of Three of the New Secretaries," no date, l-m. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box X673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN; and Theodore Geisendorf and Paul Des Gouttes, Pour les prisonniers de guerre: des Vivres certes! Mais des Livres aussi (Geneva: Sonor, S.A., 1918), 1-8. Federation des Oeuvres d'Envoise de Livres aux Prisonniers, Oeuvre des Bibliotheques Circulantes pour les Prisonniers isoles (Paris: Ravilly, n.d.), 1-4. Theodore Geisendorf, Comite Universel des U.C.J.G., Rapport sur l'Organisation a Paris d'un Comite port l'Envoi en Allemagne de Livres aux Prisonniers de Guerre isolades (Geneva: n.d.), 1-5. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid Y.M.C.A., 1914-1918: POW Camps in Germany and France." Section 43: "Germany." Publications. World's Alliance of YMCA Archives, Geneva. back

Note 18: Review of Review Editors,Two Thousand Questions and Answers About the War, 222; and Gustav A. Sigel, German Military Forces of the 19th Century (New York: Military Press, 1989; reprint of 1900 edition), 64-76. back

Note 19: E. O. Jacob, "Report of E. O. Jacob: For the Year Ending September 30, 1917," 1-15. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box 673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN. back

Note 20: E. O. Jacob, "Report of E.O. Jacob: For the Year Ending September 30, 1917," 1-15. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box 673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN; and J. Gustav White, "Prisoners-of-War at School: `Next to Bread, We Need Books,' Say Prisoners-of-War Who Go to School, Make Toys, and Learn Trades," Association Men 43 (September 1917): 16. back

Note 21: J. A. Noering, "Central Powers," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 February 1917): 39; and Alfred Lowry, Jr., "Needs of Prisoners in Bavaria," 47-48. back

Note 22: Alfred Lowry, Jr., "Needs of Prisoners in Bavaria," 47-48. back