Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Readers' Guide

Introduction The Narrative Official Stories The Participants Afrikaans Memory and Violence Final Thoughts Archive

Abbreviations Glossary

Gutenberg-e.org Columbia University Press

Chapter 2

"I Heard There Was a Riot in Soweto…:" A Narrative of June 16, 1976

We have Soweto with us.—Carol Hermer, The Diary of Maria Tholo

A Winter Morning

Warnings

1

Related essays:

Setting the Stage

Soweto: History, Geography, Society

It all began on a winter morning in June. The air was cold and heavy with the smoke of the last night's coal fires, the weak winter sun

still ineffective against the morning chill which stubbornly clung to the shadows and the stony ground. Parents had long since made their

way through the line snaking across the open ground, waiting for the green Putco busses to take them into the "sheer massiveness of the

concrete city … so intimidating, so immovable and so impressive,"1 carrying what they needed

for the day in paper bags or the occasional briefcase. Others braced themselves for the crowded platforms at Dube station, Mzimhlope, or New

Canada or huddled with their fellow workers on the back of an open-bed truck on their way to work, gathering their tan second-hand military

overcoats around them, drawing their woolen caps deeper into their faces against the morning cold.

At the Morris Isaacson High School in Central Western Jabavu, a simple sign hung at the gate: "No SBs [security branch police] Allowed. Enter at your own risk."2 At another high school in Phefeni township the word Asingeni (we will not enter) was painted on the doors.3

For several weeks already, schoolchildren at a number of schools had been staying away from classes to protest the imposition of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in schools:

It's only a matter of time before we get organised. We talk about this every day. Here in the township and at work. We talk in our own language and the whites don't understand what we say.45

Related links:

A.D. Mokoena: Testimony

Police Statement

Now the children were resolved to make a public stand, organizing a march and a one-day boycott of classes to pledge solidarity with other

schools affected by the enforcement of the Afrikaans ruling and to bring pressure to bear on the authorities to listen to the students' complaints:

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Warning 1

In Naledi that evening, a curious conversation took place between Lilli Mokganyetsi and her brother, who had already graduated from high school and was waiting "for a call to the university":

When I arrived at home, he said, are you going to demonstrate tomorrow? I said, What is "demonstration," I don't know, what are you talking about [laughs] … I'm sorry? No, he said, no, are you going to go about with placards? What is a 'placard,' then? [brother:] Poster. What is a "poster"? [laughs] You know I couldn't just understand … anything, let alone demonstration on its own. [brother:] No man, I have heard that students will be demonstrating tomorrow against this Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. I wonder what's going to happen. And I said, no, what are you talking about, do you mean we are not going to school? He said, no, man, you've got to go to school. You go to your school, they will show you how to "demonstrate." You don't understand, you!5 (See essay: "The Schools.")

Related essay:

Layers of Meaning—Testimonies in Time

The night before June 16 "was a night where we spent preparing ourselves for the march." There was no "grand plan that extended for days and for

months," although considerable, if hasty, planning had gone into the preparation for it. Murphy Morobe was among the student leaders who created

the placards for the march. The placards read simply "Away with Afrikaans" and "Down with Bantu Education." They saw themselves "on this day"

marching from different points in Soweto toward Orlando West, to one of the junior secondary schools that had been longest in boycotting classes

around the Afrikaans issue.

Related links:

Murphy Morobe

TRC testimony, 7/96

Radio 702 interview 6/16/93 The idea was that we would be marching towards that point as a way in which we are going to pledge our solidarity with that secondary school and thereafter in fact we are going to look towards the situation where we would anticipate and expect a response from the authorities in terms of our demands that we are going to place on that day. And the idea was, that subsequent to that we are going to have a mass rally, where the student leaders, Tsietsi Mashinini and them, would be able to address the students and thereafter in fact break off the march.6

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Morning

The March

10[T]he march would start in Naledi for all those schools in that area and … Naledi High School would lead them from that point of departure. That column of the march would then come down to Morris Isaacson High School, collecting all the students on the way. The schools in the Meadowlands area would come along and join up with the other Morris Isaacson column at Orlando West High School. They would then proceed as a main column to Orlando Stadium which was going to be their destination… schools in the Orlando East complex would culminate with the others at Orlando Stadium.7

At Naledi High students streamed out of their classrooms when the bell rang for morning assembly. From under their clothes they pulled posters and placards—"The Black Nation Is Not a Place for Impurities. Afrikaans Stinks"—and as they moved toward the gates of the school their voices gathered force: "Power! Away with Afrikaans" and "Free Azania, power!"8 At their head Tebello Motapanyane urged them forward, stopping only briefly to warn a white press photographer that pictures would get them into trouble with the police. The students poured out onto Nyakale Street and marched toward the Thomas Mofolo Junior Secondary School a mile away in Naledi, where 500 students had already gathered for a meeting at 7:30 that morning.

In Central Western Jabavu, the assembly bell at Morris Isaacson High School had rung at the usual time also. But as the students gathered they broke into song: "Masibulele ku Jesu, ngokuba wasifela" (Let us thank Jesus, for He died for us) without waiting for deputy headmaster Norman Malebane, who had been walking to assembly, to conduct morning prayers. Then they sang "Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika" (God bless Africa), and "marched out of the school grounds into Mphuthi Street," leaving their startled teachers behind.9

[W]hat they were singing was the anthem, that is Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika.

[…]

The other song they were singing, is an English song, "We shall overcome."10

Outside one schoolyard a big crowd of students waved placards ("Afrikaans Is a Poison") and sang ("Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika" [God bless Africa] and "Morena Vuluka").11 Another group of students, from the Morris Isaacson High School, joined them.12 As the students moved through Mofolo toward Dube they were joined by others from schools along the road, and their numbers swelled. Younger schoolchildren cheered and watched from the side of the road. Others joined the march.

15Lilli had "even forgotten" what her brother had said the night before. She prepared herself as usual and then went to her school, a secondary school in Tladi, bracing herself for the mathematics examination she was to take. But the exam was interrupted by the arrival of the students leading the march:

[T]he school was arranged in this fashion [she demonstrates]…

[HP-M: Like a horseshoe? …]

Ja, this is the administration, classes, classes and this is the square, where we hold our morning devotions. So now they came this way, and our class was here. So we came in, and joined them in the assembly there. We, of course toyi-toyed, but we never knew of toyi-toyi then [laughs]. And then, suddenly when they were to move out, we thought we were supposed to remain [laughs] … you know, because I still remember I was … , I just remained behind, thinking that everything is over now. But the teachers, principals, they were also, you know, everybody was just frightened. And then, when I was remaining behind like this, I had a boyfriend, a long-time boyfriend, he was residing in the very same street with us, but now they had moved to Orangefontein. And he was attending a certain secondary [school] in Naledi. So he saw me, he grabbed me with the hand: 'Come Lilli, come, let's go.'13

Antoinette Musi:

Cillié Testimony September 1976

Police Statement

TRC testimony, July 1996

Related essay:

Layers of Meaning—Testimonies in Time

At the Thesele Secondary School in White City, another neighborhood of Soweto, at about 8 a.m. Antoinette Musi

14 joined the other girls in her school for morning prayers.

Whilst praying, I heard a noise as though it was that of an aeroplane. Thereafter I saw a group of children carrying placards. Because we knew nothing, they came with placards singing. We then moved backwards. They then asked us to join them and we were surprised why we should join them. Some of the schoolchildren refused to join this group of children. They then forced us to join them. The principal got out of his office and told us not to join that group. They then terrified the principal; he immediately ran into his office. We then joined the group and moved away with them.15

The children, boys and girls, were singing and talking loudly among themselves and, although they "promised to assault us too," Antoinette Musi remembered that they "looked happy." She "was surprised" and "did not know exactly what to do" but left her school with the others and went to Itshetsepeng School, where they "found the schoolchildren there already outside. They also joined us." By this time the crowd of schoolchildren had grown so large that their very numbers and enthusiasm induced others to join them.16 Another 15-year-old student said, "We were at a good school, a good high school. We liked our teachers and we studied hard. But when the word went out, we knew we had to join the rest."17

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Participation

20 While they were marching the children lifted their fists in the air, and any cars they came upon were stopped. It was mostly boys who did this—"they would lift up their hands with their fists and command the driver of the car to also do the same sign." Some did and were allowed to pass; others did not.

Some of the schoolchildren would tell the others that they should leave them to go and the others would say they must be assaulted, talking amongst each other, these scholars.18

But Antoinette did not see anyone being assaulted or anything happening to their cars. Philippa Newlin Thompson, vice chairman of the African Self-Help Association, encountered such a group of students around 9:30 A.M. while visiting some of the construction work being done on four-day nurseries (preschools) of the Association. She was driving from Senaoane on the main road, which ran past the building of the Urban Bantu Council, when

I met a demonstration by hundreds of children marching towards Molapo. The children were all good humoured and obviously enjoying their demonstration. A boy of about 15 or 16 took it upon himself to guide my car slowly through the oncoming children, but after a few minutes when the wave of children seemed endless, he suggested I drive onto the parking area of a garage at Moletsane outside which I had then arrived. This I did. The children continued to march past waving banners about the abolition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. After a further 5 or 10 minutes a rather older youth came up to me and said "You must go that way" (indicating a side road) "and that is an order." As I was beginning to be concerned about the 10 am start of our meeting, I didn't hesitate, and found my way through Tladi and back onto the road.19

The Central Western Jabavu office of the West Rand Administration Board was on Mphuthi Street. Samuel S. Tlotleng's duties as a social worker included his assisting young people ("the youth") with their "reference book problems," writing affidavits for them, and referring them to the department to which they should direct their complaints. He had heard "children speaking" the day before the uprising, "saying that they were going to have a march … into Orlando stadium where they are going to have a meeting … in protest of being taught in the medium of Afrikaans." He reported to work as usual on the morning of June 16, at eight o'clock, and saw many children on their way to school. About an hour later "they came down marching, they came down Maputi Street." There were about a hundred of them carrying placards, singing freedom songs, and holding up their clenched fists in the "power salute." At the offices of the West Rand Bantu Administration the staff, including Mr. Hobkirk, who was white and who dealt with those youth seeking work permits, were all standing on the stoep (porch) and watching the march go by. Although the marchers saw Mr. Hobkirk, "[t]hey just raised their clenched fists, shouting 'power'" in English, and continued on their "orderly" way. The employees of the West Rand Administration Board "just went back to [their] normal duties."20

25By the time the schoolchildren reached Orlando High School "we were all mixed up, different uniforms … we were all together," and Antoinette Musi did not "see anybody leading."21 A male student stopped and addressed the students before they marched on to gather in front of the closed gates of Orlando West High School. He said:

Brothers and sisters, I appeal to you to keep calm and cool. We have just received a report that the police are coming. Please do not taunt them, do not do anything to them, just be cool and calm because we do not know what they are after. We are not fighting.22

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Leaders

The Confrontation

By 10:30 A.M. several thousand students had gathered on the stone-topped knoll near the Orlando West High School, on the school grounds and among the houses in the neighborhood.

Where this school is situated you can actually see the Orlando Police Station across the railroad there.23

The geography of the uprising is quite striking, in particular how the sites for police stations were clearly chosen to provide the police with a vantage point from which to literally and figuratively oversee the township. The view here is from the barred hallway window of Orlando Police Station across the valley toward the flat roofs of Phefeni Junior Secondary School and Vilakazi Street.

Witnesses said that there must have been between 5,000 and 6,000 children,24 most of them students from Naledi High School, Morris Isaacson High School, Orlando West High School, Orlando North Junior Secondary School, Empangeni Higher Primary School, Themba Sizwe Higher Primary School, and Thesele Secondary School. Lieutenant Colonel Kleingeld appealed to the students to disperse, first in Afrikaans and then even in broken Zulu. But the students "had grievances which could no longer wait."25 Their clenched fists held high, they surged forward, shouting "Amandla!" (power), "Inkululeko ngoku!" (freedom in our lifetime), and "One Azania, one nation!" One of their leaders, Hastings Ndlovu, urged them on.

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Confrontation

30

"The air resounded with menace" and, defiantly, they sang:

Asikhathali noma bes'bopha

We don't give a damn, even if imprisoned.

Sizimisel'ikululeko.

For Freedom is our ultimate goal.26

Related link:

"Banner and Poster Slogans"

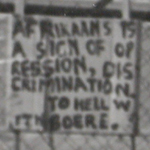

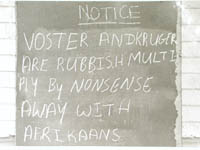

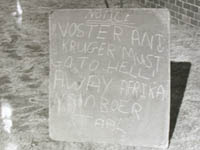

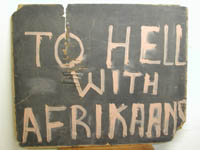

Their placards were simple, made from flattened cardboard boxes, held an arm's length high or simply tied around their bodies with

string. But their language was incendiary: "Black Power, We Want Vorster Soon," "Voster (sic) and Kruger must go to Hell," "Black

Power, Free Mandela." Later they would rip chalkboards off school walls. They cut along three sides of the canvas bags, bags in

which their mothers carried mieliemeel (corn flour) into the township, and wrote on the inside. One read, "We are being fed

the crumbs of ignorance with Afrikaans as a dangerous spoon." Others read, "Away with Afrikaans," "We do not want Afrikaans in

Azania," and "Afrikaans is a language of the oppressors."27

The story of the events that followed remains "beyond the reach of that kind of morality that normally distinguishes truth from lie." Although the versions of this story are so numerous and so varied that they give the illusion of detail and accuracy, they become impossible here to parse out and it will forever remain difficult, perhaps impossible, to re-collect "what really happened."28

Perhaps the most descriptive and harrowing account of the confrontation, at least from the point of view of the police, was that of Sergeant Marthinus Johannes Hattingh. From his vantage point in Khumalo Street he watched the children (kinders) milling about among the houses for about thirty minutes. He heard the children screaming, but could not understand what they were saying. They moved back to the school grounds of Orlando West High School, and the police followed them into Vilakazi Street. Slowly the crowd (skare)29 moved toward them. Lieutenant Colonel Kleingeld gave orders to get dogs and himself took up a position at the front of the police contingent:

35Die skare het geskreeu en plakate gehad en sekeres het rondgespring en gedans. Al die tyd besig om nader te beweeg. Vanaf hierdie distansie het die skare begin om klippe en bakstene na ons te gooi… Daar was so 'n oorverdowende lawaai…The crowds screamed and had placards and some jumped around and danced. All the time moving closer. From this distance the crowd started throwing stones and bricks at us… There was such a deafening noise…30What's this?

Hattingh Police Statement June 1976 Transcript | Document Images A Black police officer stepped up next to Kleingeld, and Hattingh saw that they both spoke to the crowds, "albei praat met die skare." But the air was filled with so much noise that he could not hear what they said. Under the circumstances, it is likely that none of the children heard them either. Murphy Morobe said "there was no visible … there was no clear communication between the police and the students in terms of what in fact they were expecting us to do."31

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Warning 2

In the middle of the street leading up to Maponya stores, the police came in the Landrover and blocked the street. But we were prepared to go past the police and stage the march and come back to our school. And the police said 'No, you people are not going to go past us.' That is when exactly the trouble started…32

Kleingeld gave the order to use tear gas, and several canisters were thrown at the crowd. Tear gas had not been used in the townships for many years, and for the students it was the first of many encounters to come.

And the teargas canister shot going off… For many people it may be teargas—but it could be, it could be real live ammunition going off.3340

Undoubtedly, many students associated the sounds of shooting with the frightening sensation of the biting tear gas, closely identifying one with the other:

The police, … of course they were throwing us with teargas, teargas, and they started shooting. Not from this group that was in Phefeni. When they came from their various police stations, or from their various directions, they were shooting other students, I don't know from where. And then they started shooting at us. And then, you know, that was the first time that you would hear the sound of a gun, like, for instance, I wasn't there when the teargas was shot, was fired at people on Enos's day. That was the very first time that I could hear the shooting of a teargas, and the gunshot of course. You know, we were … aie … it was so nice of course … [to] run away … but you only feel the pain when they teargas one… Maybe you were, [hesitates] what can I say, to say when the tear-gas was being shot, … burned, … well, it burns in the eyes and in the nose, and all those.34 (Lilli Mokganyetsi Interview)

Some of the grenades were thrown back at the police; the crowd moved ever nearer and continued to throw stones at the police. Not all of the tear-gas grenades exploded, but it was not clear why not all the grenades worked.

| Layered Narratives: | Police | Press | Cillié Commission |

Tear Gas

The tear-gas attack failed to disperse the students, and what even the official Cillié Commission called an "inept and ineffective attack" merely stiffened their resolve.35 The students moved forward. But the police tried one more thing. When the students were about 30 meters away, Colonel Kleingeld gave the command to storm the crowd with the dogs in the front.

With the lucidity that fear can impart, Hattingh described the details of what he saw:

45Ek het toe gevind dat patrolliehond CHEROKEE dood lê in die straat voor huis nr. 7294, Vilakazistraat. Daar het nog rook uit hom getrek en hy was verbrand. Daar was tekens dat hy doodgekap was. Dit is die hond van Bantoekonstabel Mamihano.I found that patrol dog Cherokee lay dead in the road in front of house no. 7294, Vilakazi Street. Smoke still rose from him and he was burned. There were signs that he had been hacked to death. It was the dog of Bantu Constable Mamihano.36What's this?

Another police officer had seen what had happened to the dog during that first police charge:

'n Swart polisiehond het by my verby gesnel en een van die Bantoe seuns oorrompel. Die skare het omgedraai om hul makker te help en die hond met klippe bestook.A black police dog whipped past me and overwhelmed one of the Bantu boys. The crowd turned around to help their friend and pelted the dog with stones.37What's this?

Justice Mamiane, who was the dog's handler, feared for his life:

Ek het nou gedink ons gaan dood gegooi word… Ons het almal op die skare afgestorm. My hond was aan 'n lang tou en ons het gestorm. Ek onthou dat hy 'n paar mense gebyt het. Hy was toe vêr van my ek sou sê 40 meter. Ek merk toe dat 'n aantal besig was om hom met stene te kap en met kieries te slaan. Ek het die tou getrek om hom terug te kry, maar van die skare het die tou vasgehou. As gevolg van die storm het die skare terug geval tot die hoek van Moema en Vilakazistrate waar hulle toe weer stelling ingeneem het. Die skare het my hond saamgesleep en aan die brand gesteek. Toe ek my hond sien was hy platgetrap.I now thought we would be stoned to death. We charged the crowd. My dog was on a long leash and we charged the crowd. I remember that he bit a few people. He was then far from me, I would say 40 meters. I realized then that a number were busy hitting him with stones and with knobkieries. I pulled the lead to get him back but some in the crowd held on to the lead. As a result of the charge, the crowds fell back to the corner of Moema and Vilakazi Streets where they then made a stand again. The crowd dragged my dog along and set him on fire. When I saw my dog he had been trampled under foot.38What's this?

Anonymous Witness 2 Cillié Testimony September 1976: Transcript

Justice Mamiane, [Bantu Constable, Nr. 155436W], canine unit: Police statement

Snarling and biting,39 the dog caused "a great deal of panic amongst the students. It was

either them or the dog at that point in time."40 The crowds fell back to the corner of

Moema and Vilakazi Streets and, for a moment, the police retreated to their vehicles.41

Notes:

Note 1: Sipho Sepamla, A Ride On The Whirlwind (London: Heinemann, 1981), 9. back

Note 2: Quoted in Harry Mashabela, Black South Africa: A People on the Boil (Johannesburg: Skotaville, 1987), 4. back

Note 3: Valentin Gorodnov, Soweto: Life and Struggles of a South African Township, tr. David Skvirsky (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1983), 161. back

Note 4: "Sowetans Speak for Themselves," in Gorodnov, Soweto, 291. back

Note 5: Lilli Mokganyetsi, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, December 1993. back

Note 6: Murphy Morobe, interview, Radio 702, 16 June 1993. back

Note 7: Aubrey Dundubele Mokoena, testimony, 7 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, Commission vol. 100, pp. 4781 ff: Mokoena recounted to the Cillié Commission a conversation with Tsietsi Mashinini about the planned route of the march of school students. While its attribution to Tsietsi Mashinini may be difficult to prove, events of the day bear out the existence of this plan. See also chapter 4 of this book. back

Note 8: See Mashabela, Black South Africa, 5. back

Note 9: Mashabela, Black South Africa, 4. back

Note 10: Murphy "Mafison" Morobe, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, file 2/3, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 102, p. 4925. back

Note 11: Sam Nzima (photographer for the newspaper The World), testimony, September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1, Commission Testimony vol. 10; and Kasparus Johannes Daniel Matthee (officer, South African Police), statement, 25 June 1976, SAB K345, vol. 86, part 6. back

Note 12: Sophie Tema, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1, Commission vols. 9 and 10. back

Note 13: Lilli Mokganyetsi, interview by Helena McCormick-Pohlandt, tape recording, Johannesburg, December 1993. back

Note 14: In Black South Africa, Harry Mashabela identifies her as "Tiny Petersen." back

Note 15: Antoinette Musi, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1, Commission vol. 9. back

Note 16: Ibid. back

Note 17: Anonymous student quoted in Gorodnov, "Sowetans Speak for Themselves," addendum to Soweto, 294. back

Note 18: Antoinette Musi, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1. Commission Testimony vol. 9. back

Note 19: Philippa Newlin Thompson (vice chairman, African Self-Help Association), memorandum to the Commission, 16 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 127, file 2/2/7, part 1. back

Note 20: Samuel S. Tlotleng, testimony, SAB, civil-court case WLD 6857/77, West Rand Bantu Administration v. Santam (WRAB v. Santam), 3909. The different spelling of Mphuthi Street here is probably phonetic, the result of a transcription of oral testimony during the trial. back

Note 21: Antoinette Musi, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1. Commission Testimony vol. 9. back

Note 22: Sophie Tema, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1, Commission Testimony vols. 9 and 10.. When the students gathered to listen to this, Sophie Tema got out of her car, with which she and the other journalists had been driving slowly ahead of the advancing students, and went to listen to what the student leader had to say to them. back

Note 23: Paul Ndaba, verbatim statement, 17 December 1995, in Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, The Soweto Uprisings: Counter-memories of June 1976 (Randburg, South Africa: Raven Press, 1998), 29. back

Note 24: Cillié Report, 2:6. back

Note 25: Mbulelo Mzamane, ed., Hungry Flames and Other Black South African Short Stories (Essex: Longman, 1986), 78. back

Note 26: Mzamane, 79. back

Note 27: Sophie Tema, testimony, 21 September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 139, file 2/3, part 1, Commission Testimony vols. 9 and 10. Other placards, compiled from black-and-white photographs of posters made by students, photographs that were part of police evidence, carried the slogan. SAB K345, vol. 84, file 2/2/1/12/12. back

Note 28: André Brink, "Stories of History: Reimagining the Past in Post-apartheid Narrative," in Negotiating the Past: The Making of Memory in South Africa, ed. Sarah Nuttall and Carli Coetzee (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1998), 35. back

Note 29: "Op die stadium het 'n groot skare saamgepak en het bestaan uit skoolkinders sowel as volwassenes" (at this point a large crowd gathered and was made up of schoolchildren and adults). It is also at this point that Hattingh's descriptive language changes, and he refers no longer to kinders (children) but to skare (crowds). Marthinus Johannes Hattingh (sergeant, South African Police, Soweto), SAB K345, vol. 85, file 2/2/1/12/12, part 4. back

Note 30: Marthinus Johannes Hattingh (sergeant, South African Police, Soweto), statement, SAB K345, vol. 85, file 2/2/1/12/12, part 4. back

Note 31: Murphy Morobe, interview, Radio 702, 16 June 1993. back

Note 32: Paul Ndaba, verbatim statement, 17 December 1995, in Ndlovu, Counter-memories, 34. back

Note 33: Murphy Morobe, interview, 16 June 1993, Radio 702. back

Note 34: Lilli Mokganyetsi, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, December 1993. "Enos's day": Lilli Mokganyetsi here is referring to an incident that happened a few weeks earlier, on 8 June 1976, when two officers from the security police, Lieutenant S. Bekker and Detective Constable A. Nthane, came looking for Enos Ngutshana, a student at Naledi High School, in connection with a matter concerning banned pamphlets. Enos Ngutshana was the SASM secretary at the school, and student leaders were under the impression that police had gone there in connection with the school strikes staged in protest against the use of Afrikaans. The Cillié Commission reports this incident as follows: "Enos was summoned to the principal's office and told to fetch his books and accompany the police. He left but did not return. After school he was found but he refused to accompany the police. Meanwhile, Constable Nthane was being intimidated by pupils; they called him a sell-out and even threatened to kill him. He was sent to the car and upon arrival there found that all four tyres had been deflated. After inspecting the car, Lieut. Bekker telephoned for reinforcements from the Jabulani police station. Black constables turned up as reinforcements, but were pelted with stones by the pupils, as were their vehicles. The car in which Lieut. Bekker had arrived was overturned and set alight… One of the students was seen cutting the telephone wires. The commanding officer of the Jabulani police station, Maj. G. J. Viljoen, received a radio report of the stone-throwing and went to the Naledi High School, where he found that Lieut. Bekker, Constable Nthane and the school principal had been cornered in the principal's office by some 800 stone-throwing pupils. The children attacked him as well; he used tear-gas and dispersed the crowd in a baton charge and with dogs. The trapped persons were released." Cillié Report, 1:92. back

Note 35: Cillié Report, 1:116. back

Note 36: Marthinus Johannes Hattingh (sergeant, South African Police, Soweto), statement, SAB K345, vol. 85, file 2/2/1/12/12, part 4. back

Note 37: Kasparus Johannes Daniel Matthee (officer, South African Police), statement, 25 June 1976, SAB K345, vol. 86, part 6. back

Note 38: Justice Mamiane (Bantu constable, no. 155436W), canine unit, undated statement, SAB K345, vol. 86. back

Note 39: Ibid. back

Note 40: Murphy Morobe, interview, Radio 702, 16 June 1993. back

Note 41: Marthinus Johannes Hattingh (sergeant, South African Police, Soweto), statement, SAB K345 vol. 85, file 2/2/1/12/12, part 4. back