Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Readers' Guide

Introduction

Abbreviations Glossary

Gutenberg-e.org Columbia University Press

Chapter 1

Introduction

"The Child Is Also Wondering What Happened to the Father"

What I do not know, I know full well that I do not know, and I envy those who will eventually know more; but I know also that, exactly like me, they will be obliged to measure, weigh, deduce, and then mistrust the deductions so produced; they will have to make allowance for the part which is true in any falsehood, and likewise reckon the eternal admixture of falsity in truth…—Marguerite Yourcenar, Zeno of Bruges

It is true that history involves a rearrangement of the past which is subject to the social, ideological, and political structures in which historians live and work. It is also true that history has been and still is, in some places, subject to conscious manipulation on the part of political regimes that oppose the truth. Nationalism and prejudices of all kinds have an impact on the way history is written…—Jacques Le Goff, History and Memory

Overview

Story Without End

On June 16, 1976, the police shot and killed Hector Pieterson on the corner of Moema and Vilakazi Street in Soweto.

Photographer Sam Nzima captured the moment on film.1

If ever there has been an image, a document from the South African past, that is both memorial and symbol, it is this photograph, which has come to epitomize the Soweto uprising of June 16, 1976. A slight boy lies dying in the arms of a fellow student. His sister runs alongside, her face distorted in fear, her hands raised as if to ward off the horror of the moment. Zolile Hector Pieterson was 13 when he was shot and killed by the South African police.

5There is little doubt that a chill wind blew through South Africa's heart when this photograph appeared on the front pages of the world's newspapers. It confirmed the terrible news that white policemen in the township of Soweto had shot and killed black schoolchildren. Like other famous photographs, such as that of the child running naked from napalm bombs in Vietnam and of the student shot at Kent State, it has taken on meaning beyond the original historical moment. This image became the symbol of resistance. It became an icon of history2—constituent part and instrument of collective history and memory. It also came to symbolize the violence that runs like a murderous streak through the history of South Africa.

A student residence at the University of the Western Cape, a secondary school and a library in the Cape, even a high school in Berlin-Kreuzberg3—all carry Hector Pieterson's name.

In the early 1990s, an old man talked to a researcher about the political turmoil in KwaNdebele in the 1980s. Deep in thought, he picked up a rock from the stony arid ground and, weighing it in his hand, reflected on how much the students in Soweto on June 16 would have appreciated such stones.

Related links:

Kevin Brand, Pieta

Kevin Brand

Twenty years after the Soweto uprising, artist Kevin Brand recreated Sam Nzima's image in black-and-white duct tape on the walls of the Cape

Town Castle. His work, entitled Pieta, was part of the 1996 Fault Lines exhibition, which focused on memory and the need to remember.

Also twenty years later, Nombulelo Elizabeth Makhubu testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that her son went into exile in 1977, fleeing police persecution. He never returned. He last corresponded with his mother from Nigeria many years ago. She has not heard from him since. There were many stories about Mbuyisa, all of them hearsay. Some said he was sick or mentally ill. Some said his body was found at a beach, others that he had been killed and his body dumped.4

10Mbuyisa Nkita Makhubu was the young man who lifted up the dying boy Hector Pieterson from the ground and carried him into history. These were the words of his mother before the Truth Commission:

I just hope somebody somewhere will say I know. I am no longer interested in hearing that I've heard about this, I want somebody who had seen and somebody who would know, because I really want to know what has happened to Mbuyisa. All of us are going to die but I do want to know how my child died and when did my child die. And I've come here because this is my last hope, that maybe the Commission could help me find out what happened to my child.

But this child [Mbuyisa's son] also does want to know what happened… The child is also wondering what happened to the father. [Emphasis added.]5

With her testimony in 1996, Nombulelo Makhubu took a striking moment of resistance in the

history of South Africa and tore it from the past, from the grasp of commemoration, memorialization, and symbolic representation, linking it to

a present where memories reside and stories about the uprising are remembered and told.

Related essay:

Story of a Photograph — Sam Nzima

Her testimony was a vivid reminder of the scale of the catastrophe of apartheid, not in simple statistical terms of the number of human-rights

violations or in the cold language of repressive government policy or historical analysis but in terms of individual loss. The almost mythical

proportions of this single photographic image, so often used in representations of the struggle against apartheid, paled both before the

enormity of a mother's pain as she tried to make sense of her loss and before the determination with which she argued for a son's rightful

search for continuity with his father's past.

Nombulelo Makhubu's testimony and appeal, heavy with the accumulated sorrow of years, served as a forceful reminder that collective memory is located in the individual, that the individual gives voice to the collective memory.6 Nombulelo Makhubu's voice was the voice of an individual thinking historically, appealing directly to every other person (professional historians and others) to think historically also, not to end the processes of history, of remembering and seeking for some form of the truth, regardless of how elusive the concept.

Her testimony also appealed directly to one of the oldest functions of history: telling the story. Her words created a direct link between her own memories of the uprising, centered around the loss of her son, and an image that had become so powerful in its symbolic weight that it threatened to eclipse the stories of those it represented—the children who stood at the epicenter of the historical moment. Linking the present to the past, she reminded us that this story has not yet ended, that it lives in the memories of those who participated or who were touched by these events, that it stills shapes the many meanings of the past for those who write or think or speak about them in the present, that it has left many questions open, questions that will not necessarily pass with the death of those who were there, for, as the mother said, "the child is also wondering what happened to the father."

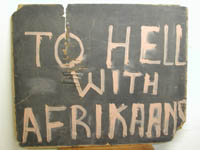

15The book before you tells the story of the Soweto uprising. It is a story 30 years old. Although the actual events of the uprising are facts of the past, the telling of them and the meaning attributed them have changed much during this time. Like all stories, this one has a beginning, a middle, and an end: the meticulous planning by the students and the many warnings to government authorities; the march to protest the imposition of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in black schools; the turn to violence and the many months of repression that followed as students continued to protest and the authorities tried to reestablish control. All of these parts this book will try to capture and describe.

The story also has a prologue. The uprising's roots in a history of growing social, political, and economic oppression based on race, as well as its roots in a history of resistance and accommodation, are central to its plot. And it has many storytellers and therefore, as one would expect, many versions or perspectives—depending on the political identity and purpose of its teller, and depending on the closeness of its teller—even at the time of its unfolding. It has two official perspectives—that of the apartheid government and that of the African National Congress (ANC) in exile—and the multiple perspectives of those who were part of the uprising or witnessed it firsthand.

Although others have done this before, this book will begin with as complete as possible a description and narrative of the events of the Soweto uprising as it unfolded. It will also, like any good history, introduce new sources, and it will introduce two lines of analysis—analysis of these events and their historical importance and contribution to our understanding of the changing nature and form of resistance in South Africa, and analysis of the simultaneous strengths and contradictions both within the South African government and within the various resistance organizations. Here I will reconsider the role of the Black Consciousness Movement in South African resistance history, and I will suggest that a careful reassessment of youth identity and youth politics allows a more nuanced understanding of the ambiguities and the lifecycles of resistance movements.

The events of Soweto were lived against a background of terrible pain and physical violence. They were almost immediately drawn into a discourse that sought to discredit and silence the participants, imparting and manipulating meaning for ideological and political reasons with little regard for how language and its absence—silences—further violated those who had experienced the events. Early on in my work, a student from one of the northern homelands of South Africa began his story about the uprising with an account of how the police prevented them from attending Steven Biko's funeral. Examples such as this reveal how people's stories have been disconnected from their reference point, the Black Consciousness Movement, and how easily such stories disappear from the accepted narrative. Perhaps because of this story, and because of the discursive erasure of the participants I saw in many accounts of the uprising, I took seriously the charge that "the people… should speak for themselves." A central principle of Black Consciousness—"It is only when the historical subjects speak as agents of history that they shape the direction of society"—it also rang true for the undertaking of the history I wanted to write and discover, a history that would require a deliberate shift of perspective toward the participants in the uprising.7

In the 30 years since June 16, 1976, political identities and purposes have changed, even as South Africa has changed, and so, to the original versions we must now add the many that have emerged over time—as, for example, when others used the story to explain their own; when anniversaries came and went; when generations grew up, grew wise, and perhaps less rebellious, or more willing to make political capital out of their historic experience; when some looked to it for reminders and celebrations of the past and while others looked to it for lessons for the future.

20The research for and writing of this book was done during a decade and a half of rapid and historic political changes in South Africa. This has led me to reconsider how history is written, how contentious and contested the sites for the production (people's memories) and preservation (the physical archives) of evidence are, and how the search for historical meaning and understanding is itself embedded in historical practices and framed by the archives at large. Three things in particular marked this time of change: (1) increasing violence, especially between 1990 and 1994, which prompted me to reconsider the effects of violence on historical memory; (2) a complete change in the political dispensation of South Africa, with the former resistance movement becoming the new government; and (3) a deliberate, conscious, and institutionalized coming to terms with the past through the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and a consequent and ongoing reassessment of the production and practices of history in South Africa.

Beyond collecting and analyzing the many stories of the uprising, this book therefore also tells the story of how the uprising fits into the narrative of the apartheid state, into the narratives of resistance, how it now fits into the TRC's comprehensive account and into the Cillié Report, how it makes a space for itself in collective remembering, how it has fared in historical analysis and how it has "apparaited" and "disapparaited" in the "archive," understood in all of its many meanings "as idea, as institution, accumulation of physical or virtual objects, profession, process, service."8

This book will describe what happened to the story of the Soweto uprising in the hands of different authors and at different times, and with what consequence. In the "official story" the character of the official changed. Clearly, in the 1970s, there were at least two institutions—the apartheid government and the ANC resistance—that claimed to speak with the authority of the official voice. The truthfulness and legitimacy of both of these accounts were marred rather badly, though—that of the apartheid government because of its secrecy and lies, that of the exiled ANC because of its physical and political distance from the events of the uprising. By the time of the twentieth anniversary of the uprising, the official voice had changed more radically than anyone could have imagined and the new government, made up now in large parts by the ANC, spoke with the new authority of the victor and with the urgent need to undo the silences and misrepresentations of the past. Although by no means its only voice, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (re)presented the official voice of the new government and, in its hands, the story of the uprising was revisited and retold.

Although we know so much, and although there have been so many versions of this story, they have given rise to many more questions—among them: Why, in the glare of so many cruel events that marked the history of apartheid oppression, does this one in particular stand out? Why does Soweto loom so large in public memory? Why, and when, did this moment take on iconographic proportions? This question becomes more complicated if one considers the ambivalence and doubt that shadowed these events, expressed in the lines from Oupa Thando Mthimkulu's 1978 poem "Nineteen seventy-six, You stand accused …"9 and, again, in Sifiso Ndlovu's Counter-memories of June 1976.10 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, initially poised to consider the uprising as a "special hearing," in the end relegated it to a place among the many chapters of resistance. What went into that decision, whether or not it reduces the importance of the story, and whether in fact the decision places the uprising in its proper place within a larger pantheon of moments in resistance history, are questions that await further research.

^topThe Uprising: Soweto Erupts

Memories of Soweto begin with police violence. (See Chapter 2: "The Narrative") For black South Africans, the confrontation

with police officers who shot at students, immediately killing two of them, transformed a demonstration by students into a violent and raging

uprising. For several weeks already, students in Soweto schools had disputed a policy change that would have forced them to study certain

nonlanguage subjects such as mathematics through the medium of Afrikaans.

Crowd marching down road

Not only did urban Africans considered Afrikaans a difficult language, but few teachers were qualified to conduct classes in that medium.

In addition, as it was the language of the police, the administration, and the hated apartheid government, its imposition as the language of instruction

in African township schools was entirely suspect. Class boycotts and other, lower-key forms of protest in higher primary and high schools had been either

subdued, discounted, or ignored.11 Finally, students from several schools in Soweto had organized the protest march.

Crowd marching down road

Not only did urban Africans considered Afrikaans a difficult language, but few teachers were qualified to conduct classes in that medium.

In addition, as it was the language of the police, the administration, and the hated apartheid government, its imposition as the language of instruction

in African township schools was entirely suspect. Class boycotts and other, lower-key forms of protest in higher primary and high schools had been either

subdued, discounted, or ignored.11 Finally, students from several schools in Soweto had organized the protest march.

25

As the students converged on Orlando West High School from all directions, the police hurriedly prepared to counter them. The two groups came to face each other in Vilakazi Street, in front of Orlando West High School in Soweto. It was 10:30 on the morning of June 16, 1976. Six thousand pupils12 in school uniforms sang, shouted, and waved placards bearing slogans such as "Away with Afrikaans," "Afrikaans is the language of the oppressors," and "We are fed the crumbs of ignorance with Afrikaans as a poisonous spoon." Their weapons were the stones that lay on the ground before them. Opposing them, 48 policemen under the command of Colonel Kleingeld, "duty bound"13 to stop them and to restore order, carried revolvers, pistols, three automatic rifles, tear-gas grenades, and riot batons. They had come in four police cars, three heavy armored vehicles, and two patrol cars with police dogs. There is conflicting evidence on almost every incident and aspect of what happened next, but within the hour two African children lay dead: 17-year-old Hastings Ndhlovu, and 13-year-old Hector Pieterson.

The students "were filled with fury and frustration by the police violence that ended the march. This led to [further] acts of violence."14 As Sibongile Mkhabela said, "We never expected it, that actually human life would be taken." When the demonstrating students heard that a boy had been shot, "that immediately changed the mood." Mkhabela's "reaction wasn't that much of fear, it was really anger. I moved from saying 'control,' to be very angry, to say there is absolutely no reason for this … it simply said there is no turning back, I can only move forward. And I marched now with more determination."15 The uprising swelled and widespread violence raged on throughout the afternoon and the night. Liquor stores and offices of the West Rand Administration Board, buildings regarded as symbols of oppression, but not only those, were burned down and looted. Vehicles and several white people were attacked, stoned, and burned. Four people died in the "riots" that morning.16 During the afternoon and evening eleven more people died, four of them under 18. All died of bullet wounds, and the police were responsible for their deaths. The commanding officer responsible for the first shooting deaths was Lieutenant Colonel Johannes Augustinus Kleingeld, a white Afrikaner. But on the day after the beginning of the Soweto uprising, a photograph depicting four policemen in uniform—two armed with pistols, the other two with sticks—appeared on the front page of The World17 under the banner headline "Soweto Rocked by Violence." The policemen were black. In an emotional eye-witness account, Derrick Thema reported in the Rand Daily Mail on June 17, 1976, that "the rioters … turned their anger on Whites and African policemen."18

The initial phase of the uprising lasted only a few days, but the unrest and clashes with the police continued with sporadic outbursts and new deaths through to the beginning of 1978. The violence was not contained to Soweto. By August 11, 1976, the uprising had spread to Cape Town, where things had remained relatively calm. But then the Cape townships of Guguletu, Langa, and Nyanga exploded, and by December more than one hundred people had been killed there and more than three hundred "youngsters" arrested. Within two months after June 16, violence had swept into 80 African communities, townships, and rural Bantustans (homelands). Two months later still, the number stood at 160.19 Soweto was everywhere.

It's happened. Cape Town is no longer the only quiet place in the country. We have Soweto with us … "Where's my child? I've come to fetch my child. Guguletu is in turmoil. We've got the Soweto riots here. The schools are on strike. The air's thick with teargas. Just go out and see."20

30

As a result of the unrest in Soweto, 312 schools with 180,000 African students were immediately closed. In Alexandra, another township on the northeast side of Johannesburg, the closing of 14 schools affected 6,000 students.21 Ninety-five black schools in Soweto, 4 in Alexandra, and 12 in the Cape Peninsula were destroyed or damaged during the uprising. The uprising claimed at least 176 lives in the first two weeks. "The total number of publicly-recorded deaths arising out of the disturbances between June 1976 and October 1977 is 700."22 Interviewed in January 1977, Tebello Motapanyane, former student and secretary-general of SASM (the South African Students' Movement) at Naledi High School, put the number considerably higher.

Tebello Motapanyane interview, Sechaba Magazine

I think they exceed one thousand two hundred (1,200) because after the first few days the Black Parents Association had a Commission of Inquiry. We discovered that in Baragwanath alone we had something like 238 people dead. There were others in the police stations, mortuaries and so on. The official figure of 176 is clearly a lie. And people are still dying.23

The South African Institute of Race Relations reported that 89 of the dead in the West Rand Area were younger than 20 years of age, 69 were between 20 and 30, and 46 were older than 30.24 There were many very young children who took part in the demonstrations, and the Institute identified 12 children younger than 11 who had died. Long lines of appalled and frightened parents trying to find their children formed in front of the Medico-Legal Laboratories and Morgue of the South African Police. A boundary had been shamelessly crossed. The violence of "Soweto," regardless of its agents, radiated across spatial and geographic, generational and racial boundaries.

^topAuthor's Story

There are many ways to "tell" Soweto—from the perspective of the volatile realities inside the townships; from the countryside, geographically removed but deeply engaged in the consciousness of change that moved the urban townships; from the undefined, abstract "elsewhere" of the title of the official investigating commission the state president appointed;25 from the state's defensive point of view; from the African National Congress's insurgent position; from the vantage points of jubilant, sometimes frightened, defiant students; from the detached, analytical point of view of the academic; from closer in time and further away; and, finally, from my own position. Soweto is in my memory. In 1976, I was a 16-year-old student attending a private German high school in a white suburb of Johannesburg. Physically and experientially removed from Soweto by reason above all of my race, the events of the uprising nevertheless loomed large in my imagination, their meaning elusive, frightening, and consequential for my own growth toward a political conscience and consciousness critical of apartheid. My work, this work, on the Soweto uprising and in the African community has thus been shaped by the multiple factors of my own identity: white, female, South African, outsider/insider, immigrant German, academic, historian.

My rendering of the story of the Soweto uprising is shaped by my own history. In all my interviews and encounters I tried to take into account how the present in which I worked may itself have shaped the way my work helped "construct" a past. But there is more to the historian's memory than the context and time of the research. I have been aware throughout my work that the relationship of my own present to my own past at a time of rapid social and political changes shaped both my research and my writing. The Soweto uprising had been an enigma to me, at once an integral part of my memory and yet forever dissociated from my experience by the physical, social, and political boundaries of unbending racial separation that had characterized my youth in white South Africa during the 1970s. Despite the abundance of newspaper and radio reports,26 despite the smoke that darkened the horizons, and despite a cacophony of rumors, my questions had been met with silence both in school and at home, and there was no place for discussion or explanation of these events. I have long been puzzled by the efficacy of the potent mixture—for whites—of silence, secrets, complicity, indifference, guilt, habit, and decree that kept the physical, social, and political separation of black and white people in South Africa so firmly in place.27 With my own education abroad in Germany and in the United States (again the consequence of a privileged educational upbringing and the choices it permitted me) and the political changes in South Africa in the 1980s and after 1990, the literal and figurative silence in my mother's house slowly gave way to my questions and I could begin to try to understand the story of the Soweto uprising that had captured my imagination and consciousness for so long. By the time I formally started my research, my long absence as well as my training as a historian had conspired to make me—in the eyes both of African (i.e., black) and of white South Africans—into an outsider.

Notes:

Note 1: "During the shooting I saw a student fall down and another student picked him up and I rushed there to take a picture. I took six sequence shots of that picture of the student, whom we later discovered that was Hector Petersen, and another student by the Umbiswe Makuba picked Hector Petersen up and Antoinette, the sister who is next to me here of Hector Petersen, she was crying hysterically alongside where Makuba was carrying Victor Petersen running towards the direction where our Press car was parked." Sam Nzima, testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 22 July 1996, Soweto Hearings, day 1. Transcript available at Truth and Reconciliation Commission, http://www.doj.gov.za/trc/trc_frameset.htm (Human Rights Violations, Submissions and Transcripts; Hearing Transcripts; Johannesburg; Antoinette Sithole [accessed 2 June 2004]). back

Note 2: A place or symbol "where memory crystallizes and secretes itself:" Pierre Nora, "Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire," Representations 26 (spring 1989): 7. back

Note 3: Hector-Peterson-Oberschule in Berlin-Kreuzberg, http://www.hpo-berlin.de/ (accessed 16 June 2004). back

Note 4: Nombulelo Elizabeth Makhubu, testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Human Rights Violations, Submissions—Questions and Answers, 30 April 1996, case GO/O133, Johannesburg, day 3. Transcript available at Truth and Reconciliation Commission, http://www.doj.gov.za/trc/trc_frameset.htm (Human Rights Violations, Hearings and Submissions; Hearing Transcripts; Johannesburg; Victim Hearings; Nombulelo Elizabeth Makhubu [accessed 19 June 2004]). back

Note 5: Ibid. back

Note 6: Susan Crane reminds us that "we all know that groups have no single brain in which to locate the memory function, but we persist in talking about memory as 'collective,' as if this remembering activity could be physically located" somewhere in the group. Susan A. Crane, "Writing the Individual Back into Collective Memory," American Historical Review 102, no. 5 (December 1997): 1381. back

Note 7: Barney Pityana, Mamphela Ramphele, Malusi Mpumlwana, and Lindy Wilson, introduction to Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 3. back

Note 8: My thanks to Carolyn Hamilton for her thoughtful and provocative commentary on my work and her contributions to this discussion in her paper "The South African Past in the Twenty-first Century," presented at the Biennial Conference of the Historical Association of South Africa, Stellenbosch, 5-7 April 2004. I am also grateful to her for reminding me to look to one of the best storytellers of our time, J. K. Rowling, for her invention of the disappearing and appearing spell in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. The spell has to be learned and mastered by the one wielding the magic wand—in this case, the wand of (archival) control: See Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, and Graeme Reid, introduction to Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 7. back

Note 9: Reprinted from Staffrider 1, no. 1 (1978), in Baruch Hirson, Year of Fire, Year of Ash. The Soweto Revolt: Roots of a Revolution? (London: Zed Press, 1979), x. back

Note 10: Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, The Soweto Uprisings: Counter-memories of June 1976 (Randburg: Ravan Press, 1998). back

Note 11: C. W. Eglin and R. M Cadman, House of Assembly, Hansard vol. 20 (17 June 1976). back

Note 12: "The Commission accepts that shortly before the confrontation there were at least six thousand people, but that more were joining their ranks continually." P. M. Cillié, Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Riots at Soweto and Elsewhere from the 16th of June to the 28th of February 1977 [hereafter Cillié Report] (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1980), 112. Conflicting estimates put the number as high as 12,000 and as low as 1,000, but many students had not yet reached the agreed-upon gathering place. back

Note 13: Cillié Report, 1:114. back

Note 14: Ibid., 1:132. back

Note 15: Sibongile Mkhabela, interview, Johannesburg, 1996, in Two Decades… Still, June 16, film produced by Loli Repanis, directed by Khalo Carlo Matabane, for SABCTV, 16 June 1996. back

Note 16: Two were black schoolchildren and two were white officials. back

Note 17: The World, published under the self-consciously black-inclusive slogan "Our Own, Our Only Paper," was considered a "Black" paper, committed to supporting the antiapartheid cause. It was later banned and many of its reporters detained, harassed, and banned for their role in reporting on the uprising. back

Note 18: Derrick Thema, "I saw Death at the Hands of Child Power," Rand Daily Mail, 17 June 1976. back

Note 19: John Kane-Berman, Soweto: Black Revolt—White Reaction (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1978), 5. back

Note 20: Carol Hermer, The Diary of Maria Tholo (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1980), 10 (entry for 13 August 1976). back

Note 21: House of Assembly, Questions and Replies, Hansard vol. 70 (21 January-24 June 1977), 373-74. back

Note 22: See Kane-Berman's careful analysis of the numbers, Soweto, 27-28. back

Note 23: Tebello Motapanyane, interview, January 1977, in Sechaba 11, no. 2 (1977): 58. link [accessed 13 June 2006] back

Note 24: South African Institute for Race Relations [hereafter SAIRR], A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa: 1976, ed. Muriel Horrell, Tony Hodgson, Suzanne Blignaut, and Sean Moroney (Johannesburg: South African Institute for Race Relations, 1977), 58 and 85. back

Note 25: South Africa, Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Riots at Soweto and Elsewhere from the 16th of June 1976 to the 28th of February 1977 [my emphasis] (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1980). The Commission is also known as the Cillié Commission and the report as the Cillié Report. back

Note 26: During 1976, South Africa was still experimenting with national television. The uprising was one of the first events reported on for television by film crews of the South African Broadcasting Corporation, and television programming was still in a test phase. Many homes such as ours and undoubtedly most African households still had no television set because of the high cost. back

Note 27: My thanks to Arif Durlik for the important discussion of these issues at the Workshop on Legacies of Authoritarianism: Cultural Production, Collective Trauma, and Global Justice, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2-5 April 1998. back