Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Readers' Guide

Introduction The Narrative Official Stories The Participants Afrikaans Memory and Violence Final Thoughts Archive

Abbreviations Glossary

Gutenberg-e.org Columbia University Press

Chapter 2

"I Heard There Was a Riot in Soweto…:" A Narrative of June 16, 1976

Aftermath

140Over the next two days the chaos deepened and the stories took on an almost surreal quality. Peter Magubane, a photographer working for the Rand Daily Mail, was on his way to work on the morning of June 18 when he drove through the Diepkloof intersection. A crowd had gathered around a dead body, another victim of the night. "The whole intersection was littered with bottles and burnt out chairs from the bar at the beerhall."103

In the midst of the apprehension and fright that gripped Soweto, rumors spread like wildfire, often about police brutality or students being intimidated into taking part in marches and further boycotts.104 At the core of many of these rumors was often more than a kernel of truth. Matthew Boyi Manyana, a reporter for the Rand Daily Mail, was working with Zwelake Sisulu in Soweto the night of the 17th. They had parked their car almost directly opposite the police station. As the night wore on, a group of about twenty youths were led into the charge office:

At one stage those who had not been severely injured, were forced to run, literally run as they walked, as they moved in pairs into the charge office… They looked scared at the time. They were running into the charge office… It would have been about 9:30, 10 o'clock at night. They were running in pairs. The police kept assaulting them with batons… About six to eight policemen… Africans and Whites… After some time the same group of youths were taken out of the charge office and led to an open ground nearby where next to which about eight corpses were lying uncovered.105

The police, mostly black officers, forced them to hop for about twenty minutes and assaulted them by "beating them up with batons and rubber hoses almost indiscriminately about the body." There was a lot of noise throughout the time they were there, Manyana and Sisulu heard people "screaming in the charge office" and they overheard someone say, "Ja, moer hom, moer hom" (Yes, murder him, murder him). After a while the youths were ordered back out of the charge office to load the corpses into a waiting mortuary van:

While the bodies were being loaded, the mortuary van driver kept kicking the youths. There were 4 youths to one body. Two would carry the corpse from the front and others holding—and two others holding the legs and they literally dumped each body into the mortuary van. The attendant who was the driver, who was wearing a white dustcoat, would punch these youths and kick them. The whole experience was quite frightening to me.106145

(See: Manyana testimony)

Some of these accounts were deeply sinister: Constable Abraham Johannes Burger, on patrol in Soweto on June 17, reported finding the partially burnt body of a 16-year-old boy lying next to the burnt-out wreckage of a Volkswagen van. Near the Meadowlands police station he encountered a man whose ears had been cut off. The next day, behind the Meadowlands post office, he was directed to the body of a young African woman, lying up against a fence:

[D]ie liggaam was gedeeltelik nakend, die privaatdeel was verbrand en 'n stukwond op die voorhoof tussen die oë asook steekwonde aan haar borste en skouers. Ons het die liggaam na Meadowlands polisiestasie geneem en daar gelaat. Terwyl die liggaam in ons sorg was, was dit nie verder beskadig nie, ons voertuig was ook nie in 'n ongeluk betrokke terwyl ons die liggaam vervoer het nie. Dit was volgens voorkoms duidelik dat die betrokke bantoevrou op 'n grusame wyse om die lewe gebring was.[T]he body was partially naked, her private parts were burned, and [there was] a knife wound between the eyes, as well as knife wounds on her breasts and shoulders. We took the body to Meadowlands police station and left it there. While the body was in our care, it was not further damaged. Our vehicle was also not involved in an accident while we were transporting the body. It was to all appearances clear that the woman concerned had been killed in the most brutal way.107

It was during the morning of Thursday, June 17, that the uprising spread to Alexandra, a township immediately north of Johannesburg, to Vosloorus and Katlehong in the East Rand, on the West Rand to Mohlakeng and Randfontein, and to the University of Zululand and the University of the North in Pietersburg. White students as the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg protested the Soweto shootings. Everywhere, demonstrators, students, and people on the streets expressed solidarity with the schoolchildren of Soweto, explicitly tying their own demonstrations and battles with the police to the activities in Soweto. The tone of the uprising changed, as did the expressions and targets of protest.

Defying predictions of how quickly the unrest would be brought under control, it gathered momentum. One night in August, police came upon eighty

"oproermakers" (rioters),

Roadblocks, Alexandra.

on the corner of 11th Avenue and Selbourne Street in Alexandra, who were stopping homeward-bound workers,

taking and burning their passbooks, and intimidating them. The rioters had also set up a roadblock on Selbournestreet. By this time the police

had already been issued "No. 9 fyn hael, ook bekend as donshael" (No. 9 fine shot, also known as fluffy shot) to shoot protestors, and they used

it on this occasion to disperse the crowd:108

Roadblocks, Alexandra.

on the corner of 11th Avenue and Selbourne Street in Alexandra, who were stopping homeward-bound workers,

taking and burning their passbooks, and intimidating them. The rioters had also set up a roadblock on Selbournestreet. By this time the police

had already been issued "No. 9 fyn hael, ook bekend as donshael" (No. 9 fine shot, also known as fluffy shot) to shoot protestors, and they used

it on this occasion to disperse the crowd:108

Die rede vir hierdie opdrag was dat traanrook slegs 'n baie beperkte uitwerking op die oproermakers in die buitelug gehad het en dat die onskuldige werkers asook lede van die publiek baie meer daronder gely het as die oproermakers self. Die oproermakers het later so gewoon geraak om die traanrook te ontwyk, dat hulle slegs na link of regs of voor die traanrook uit beweeg het. Om aan te toon hoe doelgerig die poging was wat aangewend was om die gebruik van traanrook te laat slaag, was daar reeds op hierdie tydstip 979 traanrookgranate en traanrookpatrone afgevuur op die oproermakers. Dosyne knuppel stormlope was toe reeds uitgevoer, sonder dat dit enige skynbare blywende uitwerking op die oproermakers gehad het. 'n Hele aantal knuppels was toe alreeds stukkend geslaan op die oproermakers.The reason for this order was that teargas only had a very limited effect on the rioters in the open air and that innocent workers as well as members of the public suffered much more under it than the rioters themselves. The rioters later got so used to dodging the teargas, that they simply moved to the left or to the right or out of reach of the teargas. To show how purposeful the attempt was to make the use of teargas effective, by this time already 979 teargas grenades and teargas shells had been shot at the rioters. Dozens of baton assaults had already been made, without that having any apparent lasting effect on the rioters. A whole number of batons had by then already been broken on the heads of rioters.109What's this?

150

It was already dark, so five times 500 flares were shot off to brighten the scene. Despite the blasts from the shotgun, no wounded persons

were found,110 but police confiscated 40 half-burnt passbooks that "vermoedelik deur die

oproermakers van die werkers geroof was en aan die brand gesteek is" (were presumably stolen from the workers by the rioters and

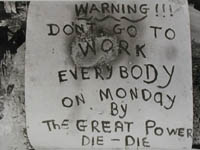

burnt).111 T. J. Swanepoel, the South African Police colonel, testified that there were posters

all over Alexandra township in August of 1976, but that their emphasis had changed:

Jacobs:

Was daar plakkate wat spesifiek oor die oorspronklike moeilikheid gegaan het, naamlik die Afrikaans as voertaal?

Swanepoel:

Behalwe vir die eerste paar dae, die twee dae wat ek daar was en toe vier of vyf dae wat ek gemis het, het ek dit nooit weer gesien nie.

Jacobs:

het nie weer iets spesifieks daaromtrent gesien nie?

Swanepoel:

Nooit weer enig—of slagspreuke op mure of plakkate, ek het dit nooit weer gesien nie… [padversperrings] … Op die hoek van 20ste Laan en Rooseveldstraat, Alexandra was byvoorbeeld een waarop die slagspreuk "Vorster se gat, een plus een is twee, Free Mandela" en met swastikas bo en onder geverf. Slagspreuke op die ou bekende kommunistiese patroon waarin geëis word dat die polisie uit 'n bepaalde onluste-gebied onttrek moet word, sodra hulle die skroef van die oproermakers begin aandraai, het oral in Alexandra begin verskyn. Sommige slagspreuke was op die teerblad van sommige strate geverf en ander op plakkate wat teen pale en geboue vasgemaak is. Hierdie taktiek word telkens in nie-kommunistiese lande gebruik. Die eis is dan ook gewoonlik: onttrek die polisie en laat die mag in die hande van die massa.Jacobs:

Were there posters that directly addressed the original difficulty, namely Afrikaans as medium of instruction?

Swanepoel:

Except for the first few days, the two days I was there and then four or five days that I missed, I never saw it again.

Jacobs:

You never again saw anything specifically about that?

Swanepoel:

Never again—neither slogans on walls nor posters, I never saw it again… [roadblocks] … On the corner of 20th Avenue and Rooseveld Street, Alexandra, there was one for example on which was painted the slogan "Vorster's [ass]hole, one plus one is two, Free Mandela" with Swastikas painted above and below. [There were] slogans on the old well known communist pattern in which it was demanded that the police should withdraw out of a given riot area, as soon as they tightened the screws on the rioters, started to appear everywhere in Alexandra. Some of the slogans were painted on the counterfoil of some streets and others on posters that were fastened to poles and buildings. This tactic is used all the times in non-communist countries. The demand is then also usually: withdraw the police and leave the power in the hands of the masses.112(See: Swanepoel Testimony)

Organizing the route out of South Africa for those sought by the police started almost immediately. Zakes Molotsi remembered:

After that everybody, more our generation, was no longer staying at his parents. We started to move out of our homes, run away, because it was a terror … because they started to pick up and detain everyone, come and search houses looking for what they say [was Black Power].113

(See: Molotsi Interview)

It was a pattern that repeated itself all over the country as police tried to round up student leaders. Sam Mashaba recalled that he decided, after several confrontations with the police:

155I was no more going to go back home because I knew that they were going to follow me at home, they knew my home very well. So I decided that I was going to hide somewhere far away from home. I went to a place about 40 km from home and that was at my brother-in-law's home, and I hid myself there. Now, some of the students had hidden in different areas, some in the township around Sibasa, some in the villages around.114

(See: Mashaba Interview)

In the townships, a complicated network of underground communication and transport helped those who wanted or needed to leave. Zakes Molotsi, who was one of the older activists of the uprising and had belonged to an underground ANC cell, described one of the routes out of the country:

Microbusses … we used them during the weekend, because is easy, most people are off work, resting at home, but we used to, we had this trick of using the football team. Go and get a poster, take about … people … so we had a football kits inside, to put off the police. Then when we reach Mafeking, from Mafeking you can't travel with that big bus towards the border. We started to group them, give them directions, we'd meet the other side of the border. That time, once you reach there, then one would take them to the border on the other side.

[…]

At the border you don't go to the border gate, you just jump the fence. We had continuous … people who go and look at new ways, so that if they discovered this route, the police already know that particular area … then we retreat to another area. 115

(See: Molotsi Interview)

He himself manned the route out of South Africa, going back and forth across the border several times to escort groups of students out of the country. Eventually "they made it impossible for me to return, I was in Botswana then." The people he had been working had been arrested. "It was difficult for me now to come back, because once one is arrested, you don't know what happens, given the process of interrogation." Molotsi feared that those who had been captured in South Africa would give his name away and "it was decided that I should remain" in Botswana. "It was really a very fateful year."116

Notes:

Note 103: See Peter Magubane, statement, 18 October 1976, Bureau of State Security (BOSS), SAB K345, vol. 13, pp. 2 and 8. back

Note 104: See Ellen Hellmann, "Soweto: August 1977," 4. back

Note 105: Matthew Boyi Manyana, testimony, September 1976, SAB K345, vol. 140, file 2/3, part 3; Commission Testimony vol. 14. back

Note 106: Ibid. back

Note 107: Abraham Johannes Burger (constable, South African Police), statement, SAB K345, vol. 86. back

Note 108: Theunis Jacobs Swanepoel (colonel, South African Police, Hillbrow), testimony, SAB K345, vol. 140, file 2/3, part 3, Commission vol. 16. back

Note 109: Theunis Jacobus Swanepoel (colonel, South African Police, Hillbrow), testimony, September 1976,

Note 110: "Geen gewondes is op die toneel gevind nie." (No wounded [people] found at the scene.) back

Note 111: Theunis Jacobus Swanepoel (colonel, South African Police, Hillbrow), testimony, SAB K345, vol. 140, file 2/3, part 3, Commission Testimony vol. 16. back

Note 112: Ibid. back

Note 113: Zakes Molotsi, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, March 1995. back

Note 114: Sam Mashaba, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, September 1993. back

Note 115: Zakes Molotsi, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, March 1995. back

Note 116: Zakes Molotsi, interview by Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, tape recording, Johannesburg, May 1995. Molotsi said he made the trip "more than seven times." Altogether, they succeeded in taking 800 people across the border. See South African Institute for Race Relations [hereafter SAIRR], A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa: 1977, ed. Muriel Horrell, Tony Hodgson, Suzanne Blignaut, and Sean Moroney (Johannesburg: South African Institute for Race Relations, 1978), 129: A "UN mission to Botswana estimated that during 1976 [alone] a total of 880 refugees had entered Botswana from S.A." back