Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Readers' Guide

Introduction The Narrative Official Stories The Participants Afrikaans Memory and Violence Final Thoughts Archive

Abbreviations Glossary

Gutenberg-e.org Columbia University Press

Essay

Story of a Photograph—Sam Nzima

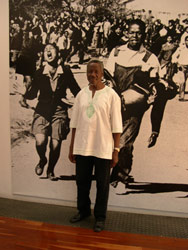

Images of the Soweto uprising have stayed with the struggle against apartheid through the years and have captured the collective imagination. As stories they became part of the discourse of liberation or, in the hands of apartheid's spokesmen, part of the rhetoric of the necessity of suppression of threats to the security of the state. As photographs they became part of the inventory of public history or, in the past, material evidence or documentation for the government's investigations. I want to return once more to the photograph with which I opened this book. The photograph has also passed through its own history, and in time, has accrued multiple layers of meaning. It is a history that began when photographer Sam Nzima took six quick shots of the three children coming toward him, shots taken before he helped take them to the nearest clinic. Realizing that he had captured a "powerful" image, he also knew that the police would want to confiscate the film. "So I quickly gave the film to our driver and told him to go straight to our office. By the afternoon the image had been transmitted worldwide." 1 Sam Nzima got no more than a 100-Rand bonus and the congratulations of his colleagues and the editors at The World newspaper. After considerable police harassment, Nzima resigned in 1977 and opened his own business, the Nzima Bottle Store, in Lilydale, close to the Mozambican border. The photograph has been used countless ways, first on newspaper pages of the world to tell the story at the time, later on T-shirts and posters to memorialize those who died in the uprising and to recall their image in support of the struggle that continued. In a massive art-installation project, it was cast onto the walls of the Castle, probably the oldest monument to colonialism in South Africa. Using squares of gray and white duct tape, artist Kevin Brand replicated the tonal dots of the newspaper photograph, on the outer wall of the Castle, for "Fault Lines: Inquiries into Truth and Reconciliation," an exhibition in Cape Town in July 1996. Organizer Jane Taylor explained that it was the purpose of the exhibition "to explore the relationship between history, memory and representation."2 Speaking before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission twenty years after he took the photographs, Sam Nzima spoke words that were a painful reminder of his loss of his authorship:

And in addition to that I am also concerned about the memorial stone which has been erected at Orlando West High. The picture of Hector Petersen has been engraved on that stone, but my name is not appearing anywhere there. I am the architect of the picture.3

Sam Nzima's photograph plucked Hector Pieterson from among the many who died and were wounded in Soweto and made him into the emblematic icon of the uprising. For many years, the other young man who died that day in the first volley of fire, Hastings Ndlovu, was forgotten. Similarly, for many years, Sam Nzima was forgotten and his famous image appropriated in countless ways. After many years of such appropriations, misuse and even wrongful attribution to other photographers of the uprising—most recently, in an article commemorating the 30th anniversary of the uprising (on June 13, 2006 in the Weekly Mail & Guardian), journalist Abhik Kumar Chanda attributed the photograph to photographer Peter Magubane—a large copy of Sam Nzima's photograph now hangs in the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto.

Notes:

Note 1: Sam Nzima, interview by Mark Gevisser, Life: The Observer Magazine, 17 April 1994. back

Note 2: Quoted in Neville Dubow, "Castle of Crossed Destinies," Weekly Mail and Guardian, 5, July 1996. back

Note 3: Sam Nzima, testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 22 July 1996, Soweto Hearings, day 1. Transcript available at Truth and Reconciliation Commission, (Human Rights Violations, Submissions and Transcripts; Hearing Transcripts; Johannesburg; Antoinette Sithole [accessed 2 June 2004]). The "counter-memories" that Ndlovu recorded are an indicator of similar battles over ownership in the collective memory (Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, The Soweto Uprisings: Counter-memories of June 1976 [Randburg: Ravan Press, 1998]). In academic circles, the debates around the explanations for the rise and origins of the student and youth organizations in South Africa also reflect a preoccupation with explanations that do not always, as Diseko pointed out, pay proper attention to the "dynamics of the organization, its sense of autonomy and the ability of its members to initiate and act independently" [emphasis added]. Diseko correctly pointed to the phenomenon and danger of subsuming an organization's history or, I would suggest, a historical event, such as the Soweto uprising, "under one political tradition which dominated it at a particular time in its history." It is equally important to recognize and acknowledge that the historian's consciousness too may be substantially shaped by the "political tradition" of the day. See Nozipho J. Diseko, "The Origins and Development of the South African Student's Movement SASM: 1968-1976," Journal of Southern African Studies 18, no. 1 (1991): 41, 43-46. back