Occupational Hazards of Cash and Credit in Kabul and Qandahar

1We can now deal with the interaction between British occupation officials and local Indian bankers, Hindkis, in Qandahar and Kabul. The relationship between colonial authorities and Indian bankers concerned both the cash and credit realms of economic exchange. The cash-based interaction unfolded primarily in Qandahar where the British encountered unexpected difficulties from their own troops when trying to institute a currency exchange-rate change. This money matter was more of a short-term concern than the credit-based exchanges between the British occupation authorities and Indian bankers in Kabul. The British occupation came to an end in the capital city they helped define as such. At its very end, the occupation force was by default led by a colonial officer who, during the most dire of straits, negotiated the receipt of large sums of cash from bankers in Kabul. These transactions posed a very real threat to the fiscal solvency of the British East India Company because of the way the Afghan occupation ended and the North Indian merchant capital that was lost as a result. The demise of Indus Army posed a long-term financial challenge for the British.

2Two general principles regarding interregional currency flows through Afghanistan during the nineteenth century are evident. The first rule is that gold currencies moved through Afghanistan in a southeasterly direction from Russia to India rather than being consumed in the country. The companion notion concerns the British Indian rupee, a silver based currency, which found a greatly expanded range of use to the northwest of Delhi as a result of Durrani state minting practices in Kabul. Before discussing the Qandahar exchange-rate change, it is important to emphasize that the movement and interaction of currencies were themselves sources of state revenue. Burnes's reformation of the Kabul customs house or chabutara during the first occupation reflects the British intent to capitalize on the movement of currency through the city.1

3Burnes's reforms of the customs house in Kabul were consistent with the basic colonial plan for the country's economy, namely, to increase revenue, streamline its collection, loosen local restraints on the flow of merchant capital, and revise the accounting practices associated with state resources. Burnes intended to centralize the collection of transit duties or rahdari on the movement of foreign goods through the country at the Kabul customs house. Consequently, his reforms reflect a severe diminution in the collection of various forms of road tolls and transit duties by local notables such as khans, foujdars, and qaladars outside of Kabul.2 Burnes was confident about the profit his reforms would reap on the movement of silver-based money, but he was especially optimistic about the profits derived from the passage of gold currencies found in Iran, Central Asia, Russia, and China, such as generic bullion, yamous, ducats and tillas, through Kabul en route to the cash siphon that was India. Burnes declared his reforms yielded a 400 percent increase in the state revenue derived from the movement of money through Kabul. He claimed Rs. 30,000 would be generated from this revised source, whereas the previous fiscal year only Rs. 6,000 was received.3

4The British were well aware of the revenue possibilities from taxing the movement of money through Kabul. Colonial officials were also very cognizant of how in Afghanistan, particularly the eastern portion of the country, Shikarpuri and other Indian bankers profited from transactions involving more than one form of currency, whether the exchange involved bills of exchange and a state money, or two metallic currencies. Elphinstone's foundational economic dictums about Afghanistan gained wide circulation and credence during more than two decades between their appearance in print and the first British invasion of the country. Occupation authorities surely heeded his opinion regarding the Hindkis of the country:

They derive their profits from lending money, which they do at an enormous interest, by negotiating bills of exchange, and by transactions connected with the fluctuations of the exchange in the place where they reside. The also mix trade and agency with their banking business. Another source of profit arises from advancing money to government for bills on the revenue of provinces, and this hazardous speculation is recommended as a premium, always large, and increasing with the risk of non-payment. Some of the bankers are very rich, but there are numberless little shops set up with very small capitals, which practice the same trade as the great ones, among the poor people of their particular neighborhood.4

5During October and November 1840, roughly a year before the occupation's demise, the British Political Agent in Qandahar, Henry Rawlinson, exchanged letters with his superior Macnaughten in Kabul about plans to institute an exchange-rate change between a local currency, the Qandahar rupee, and the Company rupee.5 Rawlinson's attempt to fashion a greater role for Company rupees in Qandahar was motivated by the success of similar efforts in Kabul. The British officers recognized the important role of the colonial army in spreading Company coin throughout occupied territory. Correspondence between Rawlinson and Macnaughten was concerned precisely with when and how to implement the local exchange-rate change. Their discussions highlight the complex relationships between the metallic currencies circulating in a given locality, and the money-market rates on hundis or bills of exchange involving at least one of the currencies affected by the proposed rate change.6 With Elphinstone's coded warning about the profits turned by Hindki bankers on exchange-rate transactions and Macnaughten's direct advice, Rawlinson certainly knew about some of the obstacles and potential dangers to the enactment of a new exchange-rate scheme, but he could not prepare for all of the possible complications. The interaction between coinage and paper credit can easily become confusing for participants and distant analysts alike, especially during conversion sequences occurring like this one when monetary values fluctuate rapidly, and no less an authority than Braudel refers to this interplay as "not only complicated but diabolical."7

6Rawlinson wanted to devalue the local Qandahar rupee by approximately 11 percent in relation to the British Indian or Company rupee. Instead of the current Qandahar Rs. 133 1/3 for every Company Rs. 100, he wanted to make the exchange rate Qandahar Rs. 150 for every Company Rs. 100.8 Rawlinson did at least two things in an effort to secure the greatest possible advantage for the Company during the transition to the new rate. Before announcing the change he quietly collected as much Company currency as possible while concurrently dispensing with the Qandahar rupees held in the Indus Army treasury.9 The Company agenda was to pay the occupation troops in its own rupees, and by taking such steps Rawlinson was trying to avoid having to enter Qandahar's hundi money market for Company rupees, which would have been both an ironic and expensive undertaking. As soon as the rate-change plan was announced or even rumored to occur, Rawlinson expected the local Hindki bankers, moneychangers, and currency dealers to elevate the bill of exchange rate from the current 4 percent to at least 10 percent, and maybe even 12 percent.10 He was trying to avoid such potentially heavy losses by having Company rupees and not the Qandahar variety on-hand. Rawlinson's surreptitious gathering of Company rupees from the local economy was successful in the sense that he achieved that end without his scheme becoming known by the local Hindki community, but it was apparently incomplete in terms of having acquired the necessary amount.

7Rawlinson was also successful in purging his treasury of Qandahar rupees, but this achievement was simultaneously viewed as a potentially worrisome point. Rawlinson knew that if he was forced to enter the hundi-based money market for Company rupees the 150:100 rate would apply to his disadvantage in the first instance. Compounding that problem was his knowledge of local banking practices which required one-third of the total value of such a transaction in Qandahar rupees as up-front security, and he now lacked that form of money. However, it was the unexpected that proved most troublesome for Rawlinson. Although he had been able to keep news of the exchange-rate change from the local Hindki banking community and dispense of Qandahar rupees, Rawlinson could not suppress information about his actions on those fronts from his own troops who cried foul. The Company troops in Qandahar held mainly Qandahar rupees, and they demanded to exchange them at the Company treasury at nothing less than the prevailing 133 1/3 to 100 rate. Now foreseeing an unexpected run on the Company's money in an amount he had not yet fully acquired, Rawlinson decided to delay instituting the new exchange rate.11

8As a result, for a short time the troops had the opportunity to dispose of some of their Qandahar currency on the open market or exchange it at the 133 1/3 to 100 rate. During this transition period of a few weeks during October and November 1840 it is unclear whether local Hindki bankers learned of the impending exchange-rate change. When the new rate was finally made official on December first, Rawlinson found himself in possession of nearly a lakh of this local money or Qandahar Rs. 1,00,000, a currency form and volume he had recently taken steps to purge from the occupation army's treasury. To dispose of this unexpected batch of devalued rupees returned by his troops, Rawlinson paid the "camel contract," or the local official in charge of providing camels used to supply and transport the occupation army.12

9Rawlinson's dilemma lay in his inability to avoid engaging Qandahar's hundi-based money market. As just noted, the everyday terms of credit provided by local Hindki bankers to the occupation army in Qandahar was 4 percent per month. This is twice the sum cited by Yang as an average amount of monthly interest charged on hundis in colonial Patna.13 Hundis or bills of exchange were the defining fiscal instrument of the Qandahar money market, and their issuance structured the circulation of cash currencies and credit and debt relations in the locality. Bills of exchange served similar purposes in other locations throughout South and Central Asia.

10According to Braudel, bills of exchange had a dual nature.14 First was their official role as a form of long-distance payment necessary in large-scale trade. More significant for our purposes is Braudel's distillation of a second function for bills of exchange, namely, a debt servicing aspect. According to Braudel, a bill of exchange could also serve as "a concealed instrument of credit at interest, an opportunity for some to lend and make their money earn profits, and for others to obtain the advances necessary to any trade."15 In nineteenth-century Afghanistan, many of those who borrowed or sought cash advances through the hundi-based money market had exhausted familial and kin-based economic support and were not fiscally solvent. For many of the economically vulnerable who sought cash from Hindki bankers, the infusion of capital they received contributed only to short-term fiscal buoyancy, say for a season or a year, after which time they would again engage the hundi-based money market for more credit and greater debt. Individual producers, smaller merchants, larger traders, local notables, and government officials throughout nineteenth-century Afghanistan were in many ways dependent on the cash advances, credit provisioning, and debt maintenance services provided by Hindki bankers.

11Before their invasion and occupation of Kabul, Qandahar, and eastern Afghanistan the British relied on bankers throughout North India who served the expanding and maturing colonial state in substantial ways, including as revenue farmers and as financiers of war. Indian bankers invested heavily in the British colonial project in all its forms, including the invasion of Afghanistan. Revenue documents from the occupation period reveal a reluctant and fragile dependence of British officials on Indian bankers. We have just seen how British occupation officers stationed in Qandahar tried in vain to evade the controlling influence exercised by Hindki bankers over the availability and interaction of different currency forms in the city. In Kabul, the most senior British authorities were similarly unable to avoid engaging local bankers, but in the capital city colonial officers sought large-scale cash advances, realized through hundis, in an unsuccessful effort to save the occupation. Given the outcome of the occupation, the final British hundi transactions in Kabul jeopardized the survival of the colonial state India.

12War and political flux usually entail significant effects on intercurrency relations that can in turn complicate hundi transactions. In occupied Afghanistan the pace of currency transformations was rapid and fluctuations in bilateral currency exchange rates such as in Qandahar occurred elsewhere in the country. Each local change exchange-rate change was a sensitive political topic and had ramifications in distant markets. For example, in Herat during the fall of 1840 Major D'Arcy Todd used invisible ink to explain and justify his withdrawal of Rs. 31,200 cash from the Company treasury.16 Todd also issued six hundis from Herat in October of that year. These bills were payable on the Bombay, Qandahar, and Ludiana treasuries, and totaled Company Rs. 68,503. However, Todd failed to indicate the exact terms of the transactions on the bills themselves, which prompted the Indian Government to write to his superior Macnaughten in Kabul who was the British official in charge of the colonial occupation. As a result, in December 1840 Macnaughten issued a circular to all colonial officers in Afghanistan concerning their issuance of hundis. Macnaughten instructed that henceforth all bills should include the rate of exchange at which the transaction occurred, and the amount of local rupees or other currency received in lieu of every 100 Company rupees.17

13A year later, during the late fall of 1841, the situation had declined considerably for the British and their occupation of Kabul. Burnes was killed on 2 November as was Macnaughten on 23 December. Major Eldred Pottinger, elderly, wounded, and apparently still in his capacity as British Political Agent at Charikar, assumed charge of negotiations with local leaders in eastern Afghanistan for a British retreat from Kabul to Peshawar. Pottinger, by default, had become responsible for the fate of approximately 16,500 people including European and Indian officers and troops, family members of European officers, and many categories of Indian laborers and camp followers forming the Army of the Indus. When he assumed the mantle of leadership Pottinger might well have held the legitimate view that he and a great many others were about to face their own mortality on the ill-fated retreat from Kabul in January 1842. However desperate he might rightly have been, his financial conduct at this time compromised the buoyancy of a number of banking firms in North India whose resources were thoroughly implicated in the fiscal infrastructure the British East India Company.

14Under siege in the British cantonment in Kabul and understandably frantic, at the very end of 1841 Pottinger issued bills of exchange payable at multiple British treasuries throughout North India for more than 13 lakhs, or over one million three hundred thousand Company rupees.18 Pottinger was clearly hoping to purchase safe passage through hostile tribal territories primarily inhabited by eastern Ghalzi Pashtuns. In return for the hefty sums of cash advanced to him Pottinger issued hundis on the Ludiana treasury for Rs. 105,000 to Rorsukh Rae, Rs. 30,000 to Dodum Rae, and Rs. 30,000 to Basha Mall. A number of other treasuries in India were affected by Pottinger's desperation hundis, but no information about recipients is given. These include bills of exchange payable at British treasuries in Ferozpore for Rs. 238,4000, in Delhi for Rs. 390,000, in Agra for Rs. 200,000, and Cawnpore for Rs. 20,000.19

15The banking firms whose representatives in Kabul advanced the cash to Pottinger had a substantial if not controlling interest in the Company's finances in North India. In the cities named earlier and elsewhere these banking firms regularly supplied the British treasuries with cash. The firms recognized the impending doom of the occupation and as a result began to restrict the flow of cash to British treasuries in North India. Their rationale in doing so was to guard against the expected losses of their capital in Kabul as a result of the British failure there. The British government also recognized the gravity of the situation in Kabul and therefore instructed their own treasury officials in Ferozpore and Ludiana to "delay without refusing remittance" on bills drawn on those treasuries.20 In response, a number of North Indian banking firms reneged outright on cashing hundis issued to the British government and its officials. The affairs in Kabul were transforming cooperative relations between North Indian bankers and colonial authorities into exchanges based on negative reciprocity. The anticipated and real losses of trans-national merchant capital in Kabul as a result of the British occupation's collapse threatened to force the closure of a number of North Indian banking firms, which in turn seriously destabilized the fiscal integrity of the British government in India.

^topGovernment Account Book Fluidity

16Before the first Anglo-Afghan war of 1839–42, colonial officials accrued basic information about the fruit produced and consumed in the area between Qandahar and Kabul. The invasion and occupation were motivated by a number of economic considerations, foremost among them being the transformation of the Indus River into a thoroughfare for commercial steamships. The British then perceived Kabul as a staging area for Central Asian traders doing business in India. Colonial policy makers envisioned the city as a node from which to direct commercial caravans carrying fruit and other commodities from the Hindu Kush mountains and further north to the planned market at Mithenkote along the Indus. At the same time the British imagined Kabul as a center of consumption in its own right, and as a site from which to launch the distribution of Indian and European goods into the markets of Bukhara and greater Central Asia. The significantly increased role for Kabul in the Indus-based commercial scheme required a pliant political edifice. The colonial Army of the Indus was conceived to restore a Durrani monarch deposed thirty years earlier, and who had since been residing in British India as a colonial state pensioner.

17The British occupation of Kabul began in September 1839, but it was not until the fall harvest of 1841 that the colonial authorities assumed full control of the kingdom's account books from their Durrani puppet Shuja. For the first two years of the occupation the British paid for Shuja's artillery, musketry, and foot soldiers who were responsible for maintaining a "superior protection of the merchant and the cultivator" when compared to the previous regime of Dost Muhammad in Kabul.21 Crediting these improved conditions, the British Envoy and Minister to Shuja's court, William Macnaughten, noted an increase of Rs. 2,25,051 over the Rs. 9,00,000 collected in taxes by Dost Muhammad the year before the occupation. However, Shuja continued appealing to his colonial patrons for more and more material support and in May of 1841 asked for Rs. 50,000 monthly to pay for his civil administration, court, and family.22 This request turned out to be the last straw, so to speak, which severed Shuja's financial umbilical cord to the British. This petition was received as presumptuous and piqued the ire of the Governor General of India who commented that Shuja appeared uninterested in using his own resources to govern. The Governor General's conviction resulted in Macnaughten assuming full fiscal responsibility for the colonially contrived polity.

18Macnaughten deputed R. S. Trevor to revise the Kabul account books and thus transform the revenue scheme of the fledgling Anglo-Durrani state. Trevor removed fiscal authority from Mulla Shakur who served as Shuja's main confidante while pensioning in Ludiana. Until his dispatch from office in Kabul Mulla Shakur was for all practical purposes Shuja's untitled finance minister, and in that capacity made a series of substantive changes to the land revenue and customs collected in and around the city during the occupation.23 For translation, explanation, and interpretation of the Kabul account books, and general information about the fiscal machinery of the Durrani state, Trevor relied quite heavily and almost exclusively on Mirza Abd al-Raziq.24 Abd al-Raziq was the main repository of knowledge about the financial infrastructure of the Kabul kingdom and the primary element of bureaucratic continuity between the revenue regimes of Mulla Shakur and Trevor during the British occupation.

19The British occupation ended with the besieged Army of the Indus attempting to retreat from Kabul in January 1842. The resulting massacre and hostage taking led to the formation of an army of retribution. During the fall of 1842 this force destroyed important parts of the commercial infrastructure in Kabul such as the Mughal era covered bazaar known as the chahar chattah, and fruit-producing villages surrounding the city such as Istalif.25 The occupation's end left the British attempt to transform Kabul's role in regional and interregional marketing networks incomplete, and the vengeful retaliation for the loss of the Army of the Indus dealt a severe blow to the local economy. However, records from the occupation, particularly the documents resulting from Trevor's revision of the Kabul account books, reveal much about the financial infrastructure of the Durrani state and how the British planned to transform Kabul into a colonial capital.26

20An increasing prominence and reliance on revenue farmers was the most noticeable theme in a wide range of alterations made by Trevor at all levels of the economy and in all territories subject to the Kabul-centered Durrani state. In terms of fruit production and marketing, which traversed and integrated many economic sectors and social groups throughout eastern Afghanistan, the British agenda was favorably designed for the community of brokers who financed and organized the export trade in that commodity. The colonial revisions of the Kabul account books created the opportunity for commercial brokers to become state-contracted revenue farmers with much greater levels of interest and influence in the fruit-laden valleys and villages surrounding Kabul.

21The fiscal restructuring of Afghanistan, though never fully realized because of the occupation's demise, was a complicated undertaking in textual terms. The Kabul account books were difficult to fully decipher in the first instance, and to restructure them in accordance with the British budget, mercantile philosophy, and political ideology was a challenging task. At the outset of his assignment, Trevor questioned the accuracy of the Durrani state revenue records and commented with a mixture of curiosity and remorse on the textual practices constituting their maintenance. Trevor qualified his own interpretation and manipulation of the state's fiscal registers by claiming the "system of public accounts" facilitated the Afghan propensity to practice fraud and graft.27

22Trevor noted a number of problematic distinctions within the Kabul account books. He presented these curiosities as evidence predisposing his revisionist task to failure, and almost pleaded for the numbers he proposed and the reasoning used to arrive at them "be considered merely as the nearest approach to the truth within my reach on a subject where much uncertainty is in my opinion quite unavoidable."28 The first and most consequential ambiguity in the Kabul account books was between the two main forms of the Durrani state's revenue, namely, money and agricultural produce. Trevor qualified his understanding of the distinction between cash and kind in the following way:

It must be observed however that the statement of the revenue in money though usual and in some respects convenient is in reality a fiction, the greatest portion of it being claimable and actually paid in kind. . . . In the Registers kept at Cabul the rule is to set down in kind whatever part of the revenue is derived from the various sorts of corn, rice, cotton, pulse and seeds yielding oil which are usually cultivated and to enter in money the dues from all other produce as fruit, melon beds, straw, clover, lucerne, sheep, etc. But even these registers give but an imperfect notion of the real state of things, there being several whole districts and parts of others in which the revenue whether of grain or money cannot possibly be levied but by taking in payment cloathes, stock furniture, cattle, or whatever else the armed force sent one a year to collect in can come by. Also when the revenue of a district is farmed, it is usual for government to bargain with the contractor for payment in cash or produce as may be convenient without reference to its exact rights, and leaving him to make the necessary arrangements with the cultivator.29

23In this testimonial about the Kabul revenue scheme, it is important to note that fruit was a commodity group clearly associated with a monetary value and that revenue farmers could bargain for combinations of cash and kind to pay for their government contracts. Trevor also noted farmers collected revenue at the time of harvesting the principal crops of each district.30 Brokers were already active in converting commodities into currency at harvest time,31 and the British planned to increase the role of revenue farming in the Durrani state's fiscal structure (see later). For the fruit-producing regions surrounding Kabul in particular the colonial fiscal regime facilitated the direct entry of commercial brokers into state revenue-farming roles. This move was designed to give brokers a greater interest in governing Afghanistan and their merchant capital wider circulation in the frontier economy between Central and South Asia and from there into the burgeoning global economy.

24Trevor also noted an unclear distinction between land revenue on the one hand, and customs and petty taxes on the other. In his discussion of the "professed separation" between those two forms of state revenue he outlined five instances where the customs and petty taxes of a district bled into the land revenue.32 Trevor was particularly perplexed at the entry of debits and credits in the Kabul fiscal registers. Any tax abolished in a district was not completely so, it seemed, because instead of disappearing from the books they were maintained textually as debits and credits of equal amounts. This allowed the amount credited to be easily resuscitated in another form as a debit when it came to the district-wide tallying of many and various kinds of revenue claims and exemptions.33 Even when landed property was confiscated by the state and became khalisa or crown lands, the tax formerly associated with the property remained in the given district's account as a debit. Furthermore, there were multiple types of crown lands and different relationships between the government and cultivators and others involved in the production process (such as those furnishing seed, implements, or animal labor) in each, all of which appeared hard for Trevor to sift through and comprehend let alone reform. For most "rules" in the Kabul accounts there appeared to be many and different kinds of exceptions. Trevor noted that "the general effect is not a little puzzling," and attached "great importance (to the) simplification of the system of public accounts."34

25From the perspectives of his superiors, the arbitrary and fluid nature of the Kabul account books presented an opportunity for Trevor to favorably reconfigure the resource base of the Durrani polity. Trevor reported the results of his efforts to Macnaughten who received instructions directly from the Governor General of India. In the cover letter of his tabular report to Macnaughten Trevor referenced Burnes' concomitant reorganization of the Kabul customs house that was an important institution known locally as the chabutara.35 Burnes claimed his reforms would increase the customs house revenue by Rs. 8,400. However, Mirza Abd al-Raziq and other central state officers told Trevor the net gain arrived at by Burnes was both inflated and a premature evaluation. Trevor opined to Macnaughten that the effectiveness of the customs house or any other account reforms could not be known until medium-range and long-term financial cycles had run their course. Trevor's uncertainty about all the Kabul-based revenue statistics reflected a set of methodological reservations about Durrani state bookkeeping practices.

26Burnes posted his numbers in May 1841 and Macnaughten forwarded them to the Governor General in Calcutta in July. Trevor's reforms were announced and forwarded in September. However, signs of the occupation's collapse became clearly evident by October.36 The timing of the reforms raises questions about the fiscal integrity of the occupation and its relationship to the North Indian colonial economy. Here it is sufficient to briefly address the reforms' temporal coincidence with the occupation's demise. The reforms were intended to increase the role of brokers and revenue farmers in the fiscal regime of the Anglo-Durrani state, but that agenda was motivated less by political than by economic exigencies. Alliances with brokers involved in the trade between South and Central Asia and other communities of financial intermediaries linking producers and revenue collectors throughout North India drew the British toward Kabul. Based on successful engagement of those intermediate commercial groups, and after many years of watching Shuja mishandle his stipends, British officials exhibited feelings of confidence and relief when they assumed full revenue command of Kabul and its dependencies. Refashioning the account books was an important step in the colonial administrative and textual creation of Afghanistan.

27Trevor was circumspect about the methodological integrity of the Kabul accounts, and issued a caveat that real reform results required a lengthy fermentation or gestation period before being fully evaluated. Nonetheless, he and Macnaughten, and presumably Mirza Abd al-Raziq to a certain extent, advocated a budget with a markedly increased reliance on commercial brokerage services. Indian financiers generally and subgroups therein, such as the ubiquitous Shikarpuri Hindus, stood to gain considerably from the British reorganization of the Kabul accounts, and this was arguably the most basic and consequential aspect of the colonial construction of Afghanistan. Shikarpuris and other Indians formed the primary class of brokers who were slated to become revenue farmers under the colonial fiscal ordering of the Durrani state. Although the first British occupation of Kabul was cut short, the 1841 colonial budget for Afghanistan had a lasting social and economic impact on the region. With Trevor's revision of the Kabul account books trans-national merchant capital and colonial business practices were noticeably advanced in this frontier region.

^topLocal Experiences of the New Fiscal Regime

28How the fruit-producing communities surrounding Kabul experienced the colonial alteration of the Durrani state revenue bureaucracy is the subject of this section. Records from the occupation reveal a variety of fiscal initiatives reflecting a common theme. During the brief period of British control over the Durrani state revenue bureaucracy localities of various dimensions around Kabul experienced a decided shift toward revenue farming. The prospect of purchasing the state's sanction to collect revenue was viewed as a favorable opportunity by the extant group of large-scale commercial brokers with already broad resource bases and diverse financial portfolios. Village fort-holders (foujdars) and other local notables claiming dues along routes of passage (rahdari) were among the groups most displaced by the colonial reforms and the revenue-farming arrangements they entailed. The following deals with the impact of the colonial revenue revisions on the Koh Daman district and the villages of Istalif and Arghandeh.

29The British occupation created the financial and textual space for commercial brokers to become revenue farmers and increase their stake in the fruit-producing villages nestled in the fertile valleys surrounding Kabul. It was noted earlier that revenue from fruit was usually, though not always, entered in the Kabul account books as money before the British assumption of full fiscal control of the nascent Afghanistan. Before Trevor's revisions in fruit-producing localities brokers were primary agents of the conversion of agricultural produce into money form. Their services facilitated the remission of cash taxes to the state and helped fulfill smaller-scale local needs for cash currency (for a number of potential reasons including but not limited to debt payment, life course ritual expenditure, and regular and irregular personal and household consumption needs).

30Commercial brokers transformed fruit into cash at harvest sites. At the same time they also initiated the marketing processes that brought eastern Afghan fruit to local consumers and the dense populace of North India. After harvest brokers arranged for one or more of the marketing steps necessary for fruit to arrive at final points of consumption. For present purposes the marketing cycle consisted of the sorting, weighing, packaging, storage, and transport of fruit to retail destinations. However, it is important to appreciate that for elements or portions of a given load this sequence could be restarted at a number of points in transit. Successful brokers of fruit may well have performed similar marketing functions for other commodities, thus making them attractive candidates to purchase revenue-farming rights in the Durrani state that were created and auctioned by the British.

31Brokers operating at harvest sites dictated the subsequent marketing course followed by the fruit produce of Kabul and eastern Afghanistan. Such marketing activity had both local and foreign dimensions as fruit and other forms of capital handled by successful commercial brokers circulated regularly between and widely within Central and South Asia. The British reformation of the Durrani state's revenue structure is notable for providing successful commercial brokers with already diverse financial portfolios the opportunity to further expand their resource base. For example, under Trevor's 1841 budget the right to collect dalali or the duty on brokerage profits earned in Kabul was farmed out for 60 percent above the previous year's rate.37 Such an increase reflects a substantially expanded role for the institution of brokerage during the colonial fiscal regime.

32The tax attached to fruit brokerage specifically was referred to as maiwadari.38 This was a tax levied on fruit sold in Kabul, but it applied only to fruit sold for subsequent export. Maiwadari was collected in Kabul at various rates according the season, the type of fruit and mode of transport (via camels, donkeys, or mules). Perhaps the most common articulation of the maiwadari tax during this period was Rs. 2 charged on a camel load of grapes exported from Kabul during the fall season. Trevor's fiscal restructuring of the Kabul accounts and revenue scheme budgeted Rs. 2,500 for the rights to the maiwadari revenue farm, which was more than a 10 percent increase from the previous fiscal year's amount of Rs. 2,240.39

33Through their revision of the government account books the British expanded the niche of brokers at the central state level. These textual transformations were intended to further concentrate the resources associated with the institution of brokerage in Kabul. From the perspective of colonial policy makers, amplifying Kabul's role as a center of interregional trade brokerage would compliment the city's recent service as a political capital.40 The colonial attempts to develop Kabul as a brokerage center expanded on the city's historical role as a wholesale market and staging area for goods in transport between Central and South Asia. The British revision of the Kabul accounts meant significant changes in the city's relationship to surrounding fruit-producing localities.

34Koh Daman was and remains the most important fruit-producing locality in the vicinity of Kabul. The district begins roughly 15 miles west of Kabul and continues to the north along the Paghman mountain range for about 30 miles. The primary plain of the Koh Daman district varies from 4 to 12 miles in length. Koh Daman is very well watered by the Ghorband and Panjsher Rivers, and the district's natural irrigation is amplified by innumerable man-made canals. For British Indian mounted troops and mobile artillery passage through Koh Daman was a near impossibility. This lush zone of fruit production was described in colonial records as being:

. . . like a garden. It is all orchards and fields, with scattered fruit trees, interspersed with numerous villages and hamlets. . . . The greater portion of the fruit brought by traders into Upper India is from the Koh Daman. Here are grown grapes of dozen different kinds, apricots of six sorts, mulberries of as many, besides endless varieties of apples, pears, peaches, walnuts, almonds, quinces, cherries, and plums . . . and (it) . . . may be considered the garden of Kabul the greater part of the cultivated land being taken up by orchards and vineyards. . . . Koh Daman is chiefly famous for its grapes and other fruits, on which the people largely subsist, besides exporting immense quantities. The grapes are of many different varieties and are cultivated with great care. Many of the houses are built with interstices in the walls for the purpose of drying the grapes and converting them into kishmish (raisins) which appear to be one of the staple articles of food in Afghanistan. . . . The apricot is the commonest fruit, and there are many different kinds varying considerably in colour and flavour; perhaps one of the best is a white fleshed variety called "kaisi." Peaches and cherries are also excellent, and large numbers of melons and watermelons are grown where the soil is suitable.41

35The British envisioned a greater role for brokers as revenue farmers at the central state level. This aspect of the colonial agenda is also evident in the most lucrative fruit-producing district outside Kabul, Koh Daman. It was mentioned earlier that income from fruit production was generally entered into the Durrani state account books as money, and for that to have occurred bankers and brokers facilitating the transformation of crops into cash were very active in Koh Daman. The colonial intervention into Koh Daman's account with the government barely altered the gross revenue provided by the district.42 Trevor's plan was a significant intervention in terms of the means of revenue collection he proposed for the district, not the amount per se. The main feature of Trevor's reform package for Koh Daman was to increase the farmed component of the district's revenue by Rs. 6,000. However, this increase was offset almost exactly by a decrease in revenue of Rs. 5,992. The latter sum was composed of tax remissions, dues considered unrealizable, and a diminution in the rights of local fort-holders (foujdars).43

36During this period, Koh Daman was a district in the Kohistan woleswali or administrative division of the Parwan province. There were a number of well-known fruit-producing villages in Koh Daman, including Ak Sarai, Charikar, Istarghij, and Totum Darrah. However, Istalif was clearly the most productive locality in the district. Of 6,495 houses found in the 41 villages then comprising the Koh Daman district, Istalif contained approximately 1,200 houses, leaving each of the remaining 40 villages with an average of roughly 158 houses.44

37As a result of Trevor's reforms revenue farming became a much more prominent aspect of Istalif's internal fiscal structure and the locality's financial relationship to Kabul and the Durrani state. The most dramatic change in Istalif's revenue structure concerned the customs and petty taxes collected in the village. The year before the British assumption of full revenue control Rs. 5,400 in customs and petty taxes were collected by local notables in Istalif. Trevor rescinded the control of local actors over the collection of that form of revenue and instead farmed out the rights to collect those dues to brokers and financiers based in Kabul for Rs. 4,000.45

38The Durrani state's purported "loss" of Rs. 1,400 in the customs and petty taxes of Istalif was supposedly "recovered" in the land revenue generated by the village, the vast preponderance of which was derived from fruit production. Ultimately, Trevor seems to have reproduced the kind of clerical practice he had originally chastised. In this instance, Trevor's bookkeeping maneuver increased the farm of Istalif's land revenue by Rs. 3,000, while simultaneously remitting Rs. 600 to the local fort-holder and Rs. 1,000 to the farmer.46 The result was a Rs. 1,400 increase in Istalif's land revenue, the rights to which were farmed out. This Rs. 1,400 increase in Istalif's land revenue farm conspicuously corresponds with the decrease in revenue resulting from the colonial plan to farm out the rights to collect the customs and petty taxes associated with the village. The reforms to Istalif's land revenue scheme and the customs and petty taxes collected there, when combined, do not alter the gross amount of state revenue generated by the village. For Istalif, the colonial revenue reforms had a far more consequential impact on the means of revenue collection, which affected various sectors of the local economy, than on the sheer amount of total revenue garnered by the state from the village.

39The British used revenue farming as an economic centralization tactic and as a method of balancing the Kabul account books. The brokers who were able to enter the revenue-farming ranks were either based in Kabul or had close ties to and substantive resources in the city. Members of the upper echelon of brokers were most likely to become revenue farmers as a result of Trevor's reforms. Their advancement came at the expense of less-successful or smaller-scale brokers whose resources were not concentrated in Kabul. Given the intensity of fruit cultivation in Istalif, and the state's accounting of that local produce in money form, brokers were certainly very active in the village economy before the British occupation.47 The British reforms of the Kabul account books and the revenue structure of the Durrani state were designed to expand the role of commercial brokers to include revenue-farming responsibilities in Istalif.

40A significant portion of fruit harvested in Koh Daman and Istalif was transported to Arghandeh, a village about ten miles west of Kabul, to be packed for export.48 For Istalif Trevor's plan rearranged and farmed out rights to collect land revenue on the one hand, and customs and petty taxes on the other, while leaving the total state revenue derived from both sources combined unchanged. Similarly, in Arghandeh the colonial budget reflects an intermingling and convolution of foreign and domestic trade considerations, and the farming of rights to collect each pool of resources, without altering the total revenue derived from the locality.

41The transit tax regimen on domestic goods circulating in the territory dubbed Afghanistan was a cause of much consternation for the British.49 Trevor's revision of the Kabul account books and revenue scheme attempted to incorporate Burnes's reformation of the customs house finances. Trevor planned to remit the Rs. 7,292 in rahdari or transit taxes paid on foreign goods moving through Arghandeh, which was in keeping with Burnes's desire to have the customs house in Kabul serve as the sole point of collecting such fees. Under Trevor's plan local authorities in Arghandeh were slated to be deprived of the right to collect this foreign transit tax revenue, while brokers in Kabul were availed of the opportunity to purchase the farm of internal transit taxes valued at Rs. 8,804.50 The difference between Rs. 8,804 for the new internal transit tax farm and Rs. 7,292 formerly collected in transit taxes on foreign goods moving through Arghandeh is Rs. 1,511.

42Trevor's plan for Arghandeh was not fully consistent with Burnes's wish to inhibit the collection by local notables of transit taxes on foreign goods moving through sites other than Kabul. Burnes intended for the Kabul customs house to receive the revenue derived from transit taxes levied on goods not produced in Afghanistan. Although it restricted the right of local authorities outside of Kabul to collect rahdari in conformity with Burnes's wishes, Trevor's plan opted to farm out the revenue derived from the movement of foreign fruit through Arghandeh, which deprived the customs house of that revenue as planned by Burnes. Trevor's accounting linked the revenue derived from the import duty on fruit routed through Arghandeh with a market tax on flour and farmed out the rights to both for Rs. 42,708. The amount of the farm Trevor proposed was Rs. 1,511 more than was collected locally during the previous fiscal year. This Rs. 1,511 mirrors the difference mentioned in the previous paragraph.

43As with Koh Daman and Istalif, Trevor's plan for Arghandeh involved a concerted move to revenue farming from Kabul as opposed to the collection of taxes on local grounds. Trevor's revisions were an attempt to balance the Kabul account books and involved a reconfiguration of existing sources of revenue. His reforms resulted in opportunities for successful commercial brokers to insinuate their resources even further into the economies of these three localities that figured so prominently in the export fruit trade.

44Trevor's reforms were announced at the beginning of September 1841, in time to take affect for the duration of that year's bountiful fall fruit-harvesting and marketing season. By the end of November 1841, the large-scale export of fruit to India was nearly complete. The preponderance of the financial activities, exchanges, and transactions associated with the harvesting, sorting, weighing, packaging, and transport of local fruit from eastern Afghanistan to markets in North India (particularly Peshawar, Kohat, and Dera Ismail Khan) had occurred. By the end of that fall's fruit-marketing season commercial brokers such as the Shikarpuris, including the more prosperous among them who became revenue farmers for the colonial state, had made the majority of their profits deriving from the British attempt to manipulate the lucrative Afghan fruit trade.

Brydon

Brydon

|

Dost Mohammed and Secretary

Dost Mohammed and Secretary

|

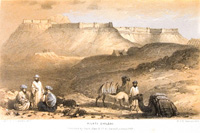

Kelat-i Ghilzai

Kelat-i Ghilzai

|

Notes

Note 1: "Increase in Cabul Commerce and Customs Duties," NAI, Foreign S.C., 2 Aug. 1841, Proceeding Nos. 61-64. back

Note 2: See Chapter 3 for more on Burnes's attempt to eliminate rahdari collection outside of Kabul. back

Note 3: Ibid. Burnes planned, perhaps unreasonably, on an almost exponential increase in the flow of these currencies as a result of his reforms. His expectations were based on the lure of a much-reduced tax charged on these moving currencies at the Kabul customs house. Burnes substantially reduced that amount from 2.5 percent to .5 percent. The rupees used his computations were Kabul kham rupees. Kham, as opposed to pukhta, rupees in the Kabul account books are addressed in Chapter 3. back

Note 4: Elphinstone, vol. I, pp. 333-334. Elphinstone also comments on the relationship between Hindki bankers and Durrani nobility. He identifies the bankers and Durranis as sharing the same interests, but the bankers worked in different though still symbiotic ways with the elite and petty Durrani nobility. The great nobles invested their money with Hindki bankers, while the lesser nobility had to "afford their protection to bankers, and treat them with great attention, in the hope of being able to borrow money from them," ibid., p. 335. Elphinstone, ibid., p. 334, also mentions dealing with bankers in Peshawar who would accept his bills, but only pay him secretly at night with money dug from the ground for the purpose. back

Note 5: "New Exchange Rate Between Qandahar and Company Rupees," NAI, Foreign S.C., 11 January 1841, Proceeding Nos. 58-60. back

Note 6: Frye, pp. 66-67 and 240, identifies the local variant of hundis in twentieth-century Afghanistan as hawalas, and emphasizes the bilateral debt-settling nature of the device by referring to it as a draft drawn on a trading associate. Frye also indicates a variety of credit standings entered into hawala transactions. back

Note 7: Braudel, p. 358. back

Note 8: "New Exchange Rate Between Qandahar and Company Rupees," NAI, Foreign S.C., 11 January 1841, Proceeding Nos. 58–60. back

Note 9: It is unclear whether Army of the Indus maintained a mobile mint in its treasury. It is appropriate to describe the location of the Qandahar mint because it aids the understanding of indigenous surveillance structures and information networks that would likely have borne on who came to know what and how about the planned exchange-rate change. The following description comes from "Qandahar: Account, Taxes, Duties," NAI, Foreign S.C., 30 April 1858, Proceeding Nos. 46–51: "In the Bazaar-i Shahi stands the 'kotwali' and mint. One kotwal, a Naib, four jemadars and twenty six chupprassies with an additional five men for the protection of the charsook is the entire police force of the City. Each jamedar has his own beat extending over about 19 muhallas each of which has a muhalladar over them who looks after the internal management of his own portion, but seldom interferes in police matters, and is not paid by government but receives a trifle at all births, marriages, and deaths." back

Note 10: "New Exchange Rate Between Qandahar and Company Rupees," NAI, Foreign S.C., 11 January 1841, Proceeding Nos. 58–60. These appear to be monthly interest rates, although their exact terms, such as when they commenced and how they were compounded, remain unclear. back

Note 11: Ibid. back

Note 12: Ibid. The recipient of the devalued currency was known as the provincial qafilabashi, or state appointed superintendent of transport. The qafilabashi would have passed any received losses on to the nomadic commercial carriers it was his duty to identify, organize, and regulate. In turn these carriers, that is, the kuchis, Lohanis, and pawindahs, would have cycled those deficits into one or a collection of exchanges and transactions remaining for that single commercial season, or more probably, rolled the losses into a forthcoming season's calculations. See Chapter 5 for more on the Durrani qafilabashi in Peshawar, and Burnes, vol. I, p. 173, for the involvement of a domestic qafilabashi in the export of purported contraband Korans. Rawlinson also considered ridding the Indus Army treasury of Qandahar rupees through advances to local officials and in remittance of hundis drawn on the Company treasury in Qandahar by British officers and agents in cities such as Herat and Farrah. back

Note 13: Yang, p. 238. Yang here refers to hundis as notes of credit whereas in another location, ibid., p. 257, he adopts the more common translation for hundi as a bill of exchange. Braudel, p. 368, distinguishes four possible handlers in a bill's life course, the purchaser, the drawer, the bearer, and the drawee who would accept the bill (or not, which might give rise to protests or a lawsuit). Of course not all individuals were required; two could suffice to complete the circuit. Levi, pp. 203-205, distinguishes hundis from bills of exchange that were written against commercial goods and could only be cashed and not deferred, transferred or sold. For a translation of hundi he prefers the compound idea of a money order and promise of payment. Levi (ibid.) notes the bond-like function of hundis that could be purchased at a 2 percent or 2.5 percent discount, and distinguishes two types of payment promises, either by distance from the point of purchase or length of time until cashing. back

Note 14: Braudel, p. 368. back

Note 15: Ibid. back

Note 16: "Instructions to Political Officers Regarding the Drawing of Bills in Cabul," NAI, Foreign S.C., 21 December 1840, Proceeding Nos. 66-68, and Foreign S.C., 28 December 1842, Proceeding Nos. 49-53. Todd's motives for using invisible ink included but were not limited to concealing financial information from local bankers and the identity of local collaborators. back

Note 17: Ibid. back

Note 18: Ibid. back

Note 19: Ibid. By this stage of the occupation's life Pottinger was not able to execute Macnaughten's orders to indicate the rate at which the hundi transaction occurred and the amount and kind of cash received. The figures given are all British Indian or Company rupees. Other British officers conducted hundi exchanges in ways that led to accusations of impropriety. See "Resources of Afghanistan," NAI, Foreign P.C., 30 March 1835, Proceeding No. 46 for Sayyid Karamat Ali's mishandling of hundis issued by Claude Wade. Wade was then the British Political Agent in Ludiana and Karamat Ali was serving as the British Newswriter in Kabul. Karamat Ali's hundi impropriety contributed to his dismissal from that post. See also N. Dupree's introduction to Lal's (1978) book on Dost Mohammad, p. xxv, where it is revealed that some of the bills Lal handled in Kabul were questioned by colonial officials and that Lal faced accusations of over-borrowing on General Pollock's account. back

Note 20: Ibid. back

Note 21: "Income and Expenses of Shuja," NAI, Foreign S.C., 24 May 1841, Proceeding Nos. 36-38. Jezailchee and janbaz are the terms used for the musketry and foot soldiers, respectively. back

Note 22: Ibid. Shuja began to receive an annual British stipend of Rs. 50,000 in Ludiana in September 1816, which included Rs. 1,500 monthly for his wife who was known as the Wuffa Begum. See PPA, Press List 2, Book 9, Serial No. 97 and Press List 3, Book 18, Serial No. 142. However both Shuja and his wife continued to regularly ask for more and different kinds of support from the British until the former's final petition in May 1841. back

Note 23: For Mulla Shakur as a "confidential servant and pre-ceptor" for Shuja see PPA, Press List 3, Book 18, Serial No. 142. For Mulla Shakur's service in all but name as the finance minister under the British-Shuja condominium see the introductory narrative to "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32-35, and Appendix O therein for the large number of tax remissions he granted during the occupation. The Shikarpuri Hindu Lala Jeth Mall served as Treasurer to Shuja during the latter's aborted attempt to regain his royal prerogative in Kabul in 1832 (see PPA, Book 141, Serial No. 68), but it is unclear whether Jeth Mall continued to serve Shuja during the British occupation. back

Note 24: It is unclear whether this Mirza Abd al-Raziq is the Munshi Abdul Razak of Delhi who Abd al-Rahman credits with opening the machine printing presses in Kabul. See Chapter 5 for more on Durrani state texts during the reign of Abd al-Rahman. back

Note 25: L. Dupree, p. 398, notes the destruction of only parts of Istalif while the Gazetteer of Afghanistan, p. 329, indicates the entire village was destroyed during the first British invasion. The chahar chatta was an innovative architectural feat for the first half of the seventeenth century and its construction is ascribed to the patronage of the Mughal official Ali Mardan Khan. The covered bazaar had four arcades that were unique for having public squares and fountains within them. The chahar chatta formed the principal retail bazaar complex in Kabul before it being leveled by the colonial army sent in retribution of the Indus Army's annihilation. The Gazetteer of Afghanistan, ibid., indicates Dost Muhammad rebuilt the structure in approximately 1850. Masson, vol. II, pp. 263–9, provides a number of useful comments about seasonal price fluctuation, fruit markets and brokerage, and the location of key institutions of Kabul commerce such as the customs house, in addition to the chahar chatta, which is described quite favorably. See Burnes, vol. I, p. 145, for a notably less enthusiastic description of the chahar chatta than Masson's. back

Note 26: "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32–35. back

Note 27: Ibid. back

Note 28: Ibid. back

Note 29: Ibid. back

Note 30: Ibid. back

Note 31: In addition to the community of brokers, the nomadic trading tribes known variously as kuchis, Lohanis, and pawindahs who transported the fruit also facilitated the entry of cash currency into fruit-producing localities (see Introduction and Chapter 1). In the fruit-based revenue regime centered on Kabul, we find brokers mediating economic relations between producers and transporters of fruit, and between those communities and the state. back

Note 32: "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32–35. back

Note 33: See later and Chapters 5 for attention to "book money" in the Durrani state financial registers. back

Note 34: Ibid. back

Note 35: Ibid., and "Increase in Cabul Commerce and Customs Duties," NAI, Foreign S.C., August 2, 1841, Proceeding Nos. 61–64. When reporting the customs house transformation to the Governor General in July 1841 Macnaughten indicated Burnes's reorganization of the most lucrative commercial institution relating to the inter regional (foreign) trade routed through Kabul resulted in a 150 percent profit on Indian and European goods transported from South to Central Asia. Burnes's reforms consisted mainly of eliminating rahdari or transit taxes collected outside of Kabul on foreign goods moving through the country. For example, for fruit rahdari was trifurcated according to the kind of fruit being transported, by what means of animal carriage, and whether the state or "chiefs and villagers" along the routes collected the dues. There were six rahdari collection points for Central Asian fruit destined for India moving the approximate 130 miles along the route segment between Bamian and Kabul. Exported Afghan fruit paid rahdari at two stations between Kabul and Ghazni. In addition to eliminating the various rahdari tolls in favor of a single tax collected in Kabul, Burnes planned to collect taxes on an increasing volume of textiles moving from South to Central Asia, and on the large amounts of opium, horses and gold currencies moving the opposite direction through the capital city. See Chapter 3 for more on Burnes's customs house reforms as they related to the movement and supply of money in and around Kabul and Qandahar during the experimental period. See Emerson and Floor for rahdari in Iran from roughly 1500 to 1750. back

Note 36: Burnes was murdered on November 2 and Macnaughten and Trevor on December 23, 1842. See L. Dupree, pp. 369–401, and Allen, Hough, Iqbal, Kaye, and Norris for more on the first Anglo-Afghan war. back

Note 37: "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32-35. The British sold the brokerage sprofit tax farm for Rs. 16,000. The previous year's entry for that account was Rs. 9,812. It is worth noting that the American adventurer Josiah Harlan also petitioned the United States Government for support in a schemes to import fruit and camels into the U.S. See Harlan (1862, 1854) and MacIntyre. back

Note 38: Ibid. The maiwadari tax was distinct from the tax on exports levied at the Kabul customs house. back

Note 39: Ibid. back

Note 40: Timur Shah transferred the Durrani capital from Qandahar in 1774. Kabul and Peshawar then shared time as the dual Durrani capital cities, the former during the summer and the latter during the winter season. Elphinstone met Shuja and gathered the bulk of his data about Kabul in Peshawar in 1809. Kabul's development as the solitary capital of an Afghanistan comprised of the Kabul, Qandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i Sharif provinces resulted from the colonial encounter. Prior conceptions of the term Afghanistan, notably Babur's, did not include all the areas or social groups associated with today's polity. back

Note 41: The Gazetteer of Afghanistan, pp. 442–7. It is important to note that citation of sources in the encyclopedic Afghanistan Gazetteer series is vague and potentially seriously misleading. Even when they appear the sources are not well referenced. The redundancy contained within original sources is perpetuated, and problematically so, in the Gazetteer series. Nevertheless, the Gazetteer pages cited here provide useful information about the social composition of the district: "Koh Daman is a favourite country residence of the wealthy inhabitants of Kabul, and is almost as thickly studded with forts as with gardens. They are strongly built, and are, in fact, mimic representations of the old baronial residences in Europe. Babar, when he conquered Afghanistan, located a number of his countrymen in the Koh Daman, the descendants of whom are now among the most prosperous in the valley." back

Note 42: "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32-35. Trevor's reforms were designed to bring in Rs. 2,42,772 whereas in the previous year Koh Damn generated Rs. 2,42,764 for the state. The difference was a mere eight rupees. back

Note 43: Ibid. Fort-holders were known locally as foujdars. Their state-sanctioned entitlements were known as foujdari. Foujdari seems to have included other local fiscal privileges known as sursat and purayana. Trevor's financial plan is notable for consistently rescinding foujdari wherever such entitlements appeared in the Kabul account books. In the case of Koh Daman the foujdari amount Trevor targeted for elimination was Rs. 2,755. back

Note 44: The Gazetteer of Afghanistan, pp. 442–7. Two villages were estimated as having 700 houses, two villages had 400 houses, three with 300, two at 200 hundred, eight with 100, and 23 villages or over 50 percent were estimated as having less than 100 houses. The same source contains entries for all the villages just mentioned in Koh Daman. back

Note 45: "Resources and Expenditure of Afghanistan, 1841," NAI, Foreign S.C., 25 October 1842, Proceeding Nos. 32-35. Such a change was in keeping with the colonial agenda of reducing rahdari tolls collected outside Kabul (see earlier). back

Note 46: Ibid. Trevor planed on Rs. 2,42,772 as the land revenue of Koh Daman. Rs. 30,480, or approximately 13 percent of that amount, was expected of Istalif. back

Note 47: Ibid. Trevor's reforms reduced dallali, or the tax on brokerage, in Istalif from Rs. 100 to Rs. 40. This move did not reflect a devaluation of brokerage as an institution because there was a far more dramatic increase in the brokerage tax at the central state level under the British revenue scheme (see earlier). back

Note 48: Ibid. About the principle Afghan export, dried and fresh fruits, Trevor noted: "[b]ut little however of either kind pass through Kabul the great fruit trade being carried on from Cohdamun direct and the duties levied at Urghundee where fresh fruit packed for exportation pays three rupees per camel load and dried fruit two rupees exclusive of kishmish (raisins) on which there is some abatement." back

Note 49: Ibid. Trevor was bewildered by the various kinds and inconsistent rates (depending on the identities of the carrier and collector) of taxation by state and local authorities on the domestic movement of "everything produced in the country which is not consumed on the spot by the producer." back

Note 50: Ibid. back