Chapter 7

Coordinating War Prisoner Relief: The American YMCA Expands WPA Work in Germany

1

With the success of Archibald Harte's POW shuttle diplomacy, in the name of reciprocity the Association found it imperative

to coordinate its various relief programs between YMCA agencies (the American YMCA, the World's Alliance, and various national

YMCA councils) and belligerent governments. In January 1916, secretaries engaged in WPA work in Germany, Austria-Hungary,

Britain, France, and Italy attended a conference in Geneva (representatives working in Russia could not attend the meeting).

This conference was convened to develop a well-knit organization that would be able to coordinate and expand WPA services

across Europe. During this meeting, the character and scope of WPA operations were clearly defined to avoid confusion

among secretaries and to achieve a common level of service. The participating secretaries also adopted fundamental principles

to guide their actions, maintain their neutral status, and meet the needs of POWs. Finally, the conferees agreed that the

World's Committee of the World's Alliance would exercise a general supervisory role over WPA activities. In March, the World's

Committee decided that the WPA program needed a strong Executive Secretary to oversee POW relief operations. He would

concentrate his efforts on executing the plans of the World's Committee on POW relief and meeting the requests arriving

from WPA Secretaries for assistance. Darius A. Davis, the American YMCA secretary sent to France to replace Carlisle V.

Hibbard (the latter had returned to New York to direct POW operations for the International Committee) arrived in Geneva

after touring French prison camps. His list of needs overwhelmed the World's Committee, and it was clear that a chief

administrator was needed. In June 1916, the World's Committee finally convinced Rudolf Horner, former General Secretary

of the Lisbon Association, to accept the position, and he set up WPA headquarters in Geneva. His work greatly increased

the efficiency of International YMCA service to POWs.1

With the success of Archibald Harte's POW shuttle diplomacy, in the name of reciprocity the Association found it imperative

to coordinate its various relief programs between YMCA agencies (the American YMCA, the World's Alliance, and various national

YMCA councils) and belligerent governments. In January 1916, secretaries engaged in WPA work in Germany, Austria-Hungary,

Britain, France, and Italy attended a conference in Geneva (representatives working in Russia could not attend the meeting).

This conference was convened to develop a well-knit organization that would be able to coordinate and expand WPA services

across Europe. During this meeting, the character and scope of WPA operations were clearly defined to avoid confusion

among secretaries and to achieve a common level of service. The participating secretaries also adopted fundamental principles

to guide their actions, maintain their neutral status, and meet the needs of POWs. Finally, the conferees agreed that the

World's Committee of the World's Alliance would exercise a general supervisory role over WPA activities. In March, the World's

Committee decided that the WPA program needed a strong Executive Secretary to oversee POW relief operations. He would

concentrate his efforts on executing the plans of the World's Committee on POW relief and meeting the requests arriving

from WPA Secretaries for assistance. Darius A. Davis, the American YMCA secretary sent to France to replace Carlisle V.

Hibbard (the latter had returned to New York to direct POW operations for the International Committee) arrived in Geneva

after touring French prison camps. His list of needs overwhelmed the World's Committee, and it was clear that a chief

administrator was needed. In June 1916, the World's Committee finally convinced Rudolf Horner, former General Secretary

of the Lisbon Association, to accept the position, and he set up WPA headquarters in Geneva. His work greatly increased

the efficiency of International YMCA service to POWs.1

While some administrative problems were solved by the Geneva Conference in January 1916, other concerns emerged. Belligerent

governments became suspicious of neutral secretaries who worked in their countries traveling to other nations to meet with

representatives who were working in enemy states. The threat of espionage or propaganda became a pressing issue. Another WPA

Secretary Conference, scheduled for Copenhagen in April 1916, had to be canceled due to diplomatic problems. More importantly,

the decision to concentrate WPA operations under the World's Committee in Geneva was not fully accepted by all American

secretaries. Harte continued to act independently as the American YMCA's International General Secretary in his work in

Central and Eastern Europe.2

While some administrative problems were solved by the Geneva Conference in January 1916, other concerns emerged. Belligerent

governments became suspicious of neutral secretaries who worked in their countries traveling to other nations to meet with

representatives who were working in enemy states. The threat of espionage or propaganda became a pressing issue. Another WPA

Secretary Conference, scheduled for Copenhagen in April 1916, had to be canceled due to diplomatic problems. More importantly,

the decision to concentrate WPA operations under the World's Committee in Geneva was not fully accepted by all American

secretaries. Harte continued to act independently as the American YMCA's International General Secretary in his work in

Central and Eastern Europe.2

While the World's Committee strove to establish a more effective international system, Harte developed strong national YMCA committees to promote WPA operations within belligerent nations. During a trip to Petrograd, Harte developed an efficient national organization for POW relief operations in Russia. This national committee enjoyed strong leadership and gained several important rights, including permission to use the official tsarist seal, bank funds, and transact business within the Russian Empire. The key to its successful organization was the Russian demand that similar national organizations be established in Germany and the Dual Monarchy.3

On 8-9 April 1916, Harte called a special meeting of the Deutsches Kommitee der Kriegsgefangenenhilfe der Christlicher Vereine jünger Männer (German YMCA WPA Committee) at the War Prisoners' Department of the Ministry of War in Berlin to make POW relief work in Germany more efficient. This conference finally established the reciprocal service to Russian POWs in Germany that had been created for German prisoners in Russia. The German authorities heartily supported Harte's proposal, and agreed to adopt his recommendations. Participants at this conference included the members of the War Prisoners' Department: Prince Max of Baden (Chairman of the War Prisoners' Department); Freiherr Friedrich von Pourtales (Vice Chairman of the War Prisoners' Department and former Ambassador to St. Petersburg); Cavalry General Kurt W. von Pfuel (Chairman of the Central Committee of the German Red Cross); Dr. von Studt (German Red Cross and retired Minister of State); Freiherr von Spitzenburg (Privy Counselor of Her Imperial Highness, Kaiserin Augusta Victoria); Major-General Friedrich (Prisoner-of-War Department, Ministry of War); Major Bauer (Prisoner-of-War Department); Captain Freiherr von Bönigk (Prisoner-of-War Department); Professor Thomas C. Hall (an American exchange professor and American YMCA advocate); Harte; Dr. Gerhard Niedermeyer (National Secretary of the DCSV); Georg Michaelis (Undersecretary of State and Chairman of the DCSV); Conrad Hoffman; and G. Rosenkranz and Herr Meyer (members of the German National YMCA Committee). Honorary committee members included Ambassador James W. Gerard (representing the United States), Ambassador Polo de Bernabe (Spain), Ambassador Count Moltke (Denmark), and Ambassador Count Taube (Sweden), all members of the diplomatic corps representing Allied interests in Germany. To streamline bureaucratic decision-making, the members of the War Prisoners' Department appointed a Special Executive Committee, which included Prince Max (Honorary Chairman), Hall (Chairman), von Bönigk, Niedermeyer, and Hoffman. The Special Executive Committee conducted daily operations, and reported to the full committee at its meetings.4

5

In policies adopted at the April conference, the War Prisoners' Department agreed to render services to Russian prisoners

in Germany on the same basis that the Russians had granted to the American YMCA secretaries in Russia. These services and

responsibilities were described as follows:

In policies adopted at the April conference, the War Prisoners' Department agreed to render services to Russian prisoners

in Germany on the same basis that the Russians had granted to the American YMCA secretaries in Russia. These services and

responsibilities were described as follows:

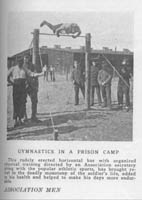

The work of the secretaries shall consist in promoting and developing with utilization to the fullest extent possible of the prisoners themselves, the following features:

- Halls or barracks for religious services, schools, etc.

- Equipment for athletics, gymnastics, and playgrounds, using YMCA funds for this purpose.

- Handicraft work of all kinds, by supplying the necessary tools and raw material for the same.

- Libraries.

- Baths and washing facilities where necessary.

- Hospitals, disinfectant equipment, medical supplies, bandage materials, etc.

- Equipment for dental work.

- Distribution of food parcels; method to be determined and regulated by the Executive Committee.

- Extension or erection of adequate canteen facilities.

- Transmission of moneys, making advancement of funds and arrangements for adequate exchange. To be under the control of the Executive Committee.5

This document was signed by Prince Max, Friedrich, and Harte, and represented an important victory in Association POW diplomacy. For Harte, this arrangement represented a blueprint for establishing a YMCA organization inside a military prison. More importantly, this became the basis for all subsequent Association POW work in Germany for the remainder of the war. The one major drawback to the plan was the German stipulation that all welfare work for POWs would be conducted by neutral secretaries.6

The National WPA Committee plan was subsequently accepted by the Austro-Hungarians, British, French, and Italians. The

actual implementation of WPA operations became very complicated. A Russian prisoner in Germany could make a request through

the YMCA Field Secretary; the Association secretary conveyed it to the German National WPA Committee, which forwarded the

petition to the German Ministry of War; if the Ministry of War approved it, permission was transmitted to the Russian

National WPA Committee in Petrograd; the Russian National WPA Committee would then send a YMCA secretary to obtain the

desired item and send it, via the German National WPA Committee and a YMCA Field Secretary, to the Russian POW. Desired

items were wide-ranging in scope, including books, food, clothing, musical instruments, tools, money, athletic equipment,

Bibles, religious paraphernalia, theatrical equipment, handicraft supplies, and information. As a result of Harte's

diplomacy in the spring of 1916, Fred Haggard became the National YMCA Secretary for Russia, Hoffman for Germany, and

Edgar MacNaughten for Austria-Hungary. Harte, as International General Secretary, represented the International Committee

and served as their supervisor for POW relief operations. To cement the ties of reciprocity, Harte arranged a meeting

between representatives of the German and Russian Ministries of War in Copenhagen. He wished to facilitate the operations

of the WPA organizations he had helped to create; however, the contingencies of the war prevented the military delegates

from meeting in the neutral capital.7

The National WPA Committee plan was subsequently accepted by the Austro-Hungarians, British, French, and Italians. The

actual implementation of WPA operations became very complicated. A Russian prisoner in Germany could make a request through

the YMCA Field Secretary; the Association secretary conveyed it to the German National WPA Committee, which forwarded the

petition to the German Ministry of War; if the Ministry of War approved it, permission was transmitted to the Russian

National WPA Committee in Petrograd; the Russian National WPA Committee would then send a YMCA secretary to obtain the

desired item and send it, via the German National WPA Committee and a YMCA Field Secretary, to the Russian POW. Desired

items were wide-ranging in scope, including books, food, clothing, musical instruments, tools, money, athletic equipment,

Bibles, religious paraphernalia, theatrical equipment, handicraft supplies, and information. As a result of Harte's

diplomacy in the spring of 1916, Fred Haggard became the National YMCA Secretary for Russia, Hoffman for Germany, and

Edgar MacNaughten for Austria-Hungary. Harte, as International General Secretary, represented the International Committee

and served as their supervisor for POW relief operations. To cement the ties of reciprocity, Harte arranged a meeting

between representatives of the German and Russian Ministries of War in Copenhagen. He wished to facilitate the operations

of the WPA organizations he had helped to create; however, the contingencies of the war prevented the military delegates

from meeting in the neutral capital.7

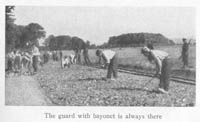

Hoffman reported that the American field secretaries had established cordial relations with most German camp officials.

Prison camp officials extended considerable privileges to Association secretaries so they could carry out the Red Triangle

program. Problems arose from time to time, some of which led to serious incidents. During a visit to a prison camp, a

secretary accepted a postcard from a prisoner. All secretaries had been warned never to bring into or take out of a prison

camp any written or printed material without submitting it to the camp censor for approval. He attempted to drop the

card off at the censor's office, but the door was locked, and he absent-mindedly left it in his pocket. When he was

departing the camp, a guard asked if he had received any written material from the POWs, and the secretary produced

the postcard. The camp commandant reported the incident to the Corps Commander and, despite Hoffman's protests, the

secretary had to be removed from German service. The American Senior Secretary suspected that a camp official had set

a trap for the unwary field secretary. On another occasion, a secretary was shaking hands with POWs. One prisoner

pressed a note into the palm of the American's hand. Fortunately, the Red Triangle worker was able to dispose of the note

without notice by the German official accompanying him. The YMCA was also indirectly involved in a POW escape. The

Association was sponsoring a two-day track and athletic meet at a prison camp. To prepare for the event, the field

secretary sent a POW on an errand, and the prisoner never returned. The YMCA immediately came under suspicion, and

Hoffman had to do a lot of explaining to clear the organization's name. The track meet was, of course, canceled and

the POWs came under increased supervision with curtailed privileges.8

Hoffman reported that the American field secretaries had established cordial relations with most German camp officials.

Prison camp officials extended considerable privileges to Association secretaries so they could carry out the Red Triangle

program. Problems arose from time to time, some of which led to serious incidents. During a visit to a prison camp, a

secretary accepted a postcard from a prisoner. All secretaries had been warned never to bring into or take out of a prison

camp any written or printed material without submitting it to the camp censor for approval. He attempted to drop the

card off at the censor's office, but the door was locked, and he absent-mindedly left it in his pocket. When he was

departing the camp, a guard asked if he had received any written material from the POWs, and the secretary produced

the postcard. The camp commandant reported the incident to the Corps Commander and, despite Hoffman's protests, the

secretary had to be removed from German service. The American Senior Secretary suspected that a camp official had set

a trap for the unwary field secretary. On another occasion, a secretary was shaking hands with POWs. One prisoner

pressed a note into the palm of the American's hand. Fortunately, the Red Triangle worker was able to dispose of the note

without notice by the German official accompanying him. The YMCA was also indirectly involved in a POW escape. The

Association was sponsoring a two-day track and athletic meet at a prison camp. To prepare for the event, the field

secretary sent a POW on an errand, and the prisoner never returned. The YMCA immediately came under suspicion, and

Hoffman had to do a lot of explaining to clear the organization's name. The track meet was, of course, canceled and

the POWs came under increased supervision with curtailed privileges.8

By the spring of 1916, the Germans countermanded the privilege of American secretaries to speak to POWs privately, a

condition that was part of the original YMCA agreement (U.S. government officials also lost this privilege in July 1916).

As a result, a German interpreter had to accompany the field secretaries on prison camp visits. This led to serious

problems. Interpreters had to leave their duties in the censor's office for several hours, which lengthened their shift,

and the secretaries became an unwelcome annoyance. In addition, the confidence of POWs waned in the presence of German

interpreters. In response, Hoffman urged YMCA workers to win the friendship of the camp interpreters and to

visit camps as often as possible. Over several weeks, the interpreters came to know the field secretaries. Finding them

to be reliable and trustworthy, they allowed most secretaries to soon renew their former practice of visiting the

POWs unattended, as the interpreters stayed at work in the censor's office.9

By the spring of 1916, the Germans countermanded the privilege of American secretaries to speak to POWs privately, a

condition that was part of the original YMCA agreement (U.S. government officials also lost this privilege in July 1916).

As a result, a German interpreter had to accompany the field secretaries on prison camp visits. This led to serious

problems. Interpreters had to leave their duties in the censor's office for several hours, which lengthened their shift,

and the secretaries became an unwelcome annoyance. In addition, the confidence of POWs waned in the presence of German

interpreters. In response, Hoffman urged YMCA workers to win the friendship of the camp interpreters and to

visit camps as often as possible. Over several weeks, the interpreters came to know the field secretaries. Finding them

to be reliable and trustworthy, they allowed most secretaries to soon renew their former practice of visiting the

POWs unattended, as the interpreters stayed at work in the censor's office.9

Hoffman sent repeated appeals and petitions to the Ministry of War to gain greater freedom for American WPA secretaries.

He finally succeeded in getting the War Ministry to allow individual corps commanders to decide about such privileges.

Hoffman then approached several generals and gained the confidence of the commander of the IV Army Corps, stationed in

Magdeburg. He granted WPA secretaries official permission to visit prison camps in his jurisdiction without the required

German guide or interpreter. Hoffman received similar permits from several other corps commanders, but the commander of

the III Army Corps in Berlin rejected the request and sent an official protest to the Ministry of War. He demanded that

other corps commanders who had issued permits to withdraw the privilege of unaccompanied visits immediately, and they

complied.10

Hoffman sent repeated appeals and petitions to the Ministry of War to gain greater freedom for American WPA secretaries.

He finally succeeded in getting the War Ministry to allow individual corps commanders to decide about such privileges.

Hoffman then approached several generals and gained the confidence of the commander of the IV Army Corps, stationed in

Magdeburg. He granted WPA secretaries official permission to visit prison camps in his jurisdiction without the required

German guide or interpreter. Hoffman received similar permits from several other corps commanders, but the commander of

the III Army Corps in Berlin rejected the request and sent an official protest to the Ministry of War. He demanded that

other corps commanders who had issued permits to withdraw the privilege of unaccompanied visits immediately, and they

complied.10

10

By early May 1916, the American YMCA reported confidentially to the organization's financial supporters regarding the

extent of WPA efforts in German prison camps. By this time, the WPA in Germany had one Swedish and four American

secretaries conducting POW relief operations. Services included the promotion of religious services, the organization

of education classes, support for arts and handicrafts, the supply of athletic and musical supplies, presentation of

stereopticon lectures, the staging of evangelistic meetings, and the organization of information bureaus to handle

enquiries regarding missing men. By this time, the American YMCA had constructed Association halls at Göttingen,

Crossen-an-der-Oder, Danzig, Ruhleben, Frankfurt-am-Main, and Senne III, and the Germans had provided the YMCA with

barracks for Association use at Giessen, Worms, and Döberitz. In addition, Association programs were underway at

Münster II and Senne II, both in Westphalia; Schneidemühl; and Dyrotz. Hoffman, Harte, and James E. Sprunger

had already conducted extensive prison camp visitations, and new secretaries were beginning work in the field.11

By early May 1916, the American YMCA reported confidentially to the organization's financial supporters regarding the

extent of WPA efforts in German prison camps. By this time, the WPA in Germany had one Swedish and four American

secretaries conducting POW relief operations. Services included the promotion of religious services, the organization

of education classes, support for arts and handicrafts, the supply of athletic and musical supplies, presentation of

stereopticon lectures, the staging of evangelistic meetings, and the organization of information bureaus to handle

enquiries regarding missing men. By this time, the American YMCA had constructed Association halls at Göttingen,

Crossen-an-der-Oder, Danzig, Ruhleben, Frankfurt-am-Main, and Senne III, and the Germans had provided the YMCA with

barracks for Association use at Giessen, Worms, and Döberitz. In addition, Association programs were underway at

Münster II and Senne II, both in Westphalia; Schneidemühl; and Dyrotz. Hoffman, Harte, and James E. Sprunger

had already conducted extensive prison camp visitations, and new secretaries were beginning work in the field.11

Mott's Second European Trip

Due to the continued conflagration of war and the greatly mounting welfare needs of Europe, John R. Mott returned during

the late spring of 1916. Mott told the International Committee of the "call that had come to him from many sources to

visit Europe and of the urgent necessity of his inspecting the War Work and of conferring with the secretaries on their

difficult problems and on their rapidly expanding opportunities." On May 29, he sailed from New York through submarine

infested waters, arriving at Aberdeen on June 7 (the Battle of Jutland had just taken place in the North Sea). After

visiting American, English, and French YMCA officials in Britain and France, the General Secretary traveled to Geneva

in June. He met with World's Committee members and International Red Cross representatives. Most importantly, he attended

a three-day conference on POW relief, attended by WPA secretaries from all of the belligerent nations. Mott was so

impressed with the need for and the opportunity of this work that he cabled New York for twenty additional supervising

secretaries to expand the current WPA force. He estimated that at least sixty-five men were needed for war prison relief

work alone.12

Due to the continued conflagration of war and the greatly mounting welfare needs of Europe, John R. Mott returned during

the late spring of 1916. Mott told the International Committee of the "call that had come to him from many sources to

visit Europe and of the urgent necessity of his inspecting the War Work and of conferring with the secretaries on their

difficult problems and on their rapidly expanding opportunities." On May 29, he sailed from New York through submarine

infested waters, arriving at Aberdeen on June 7 (the Battle of Jutland had just taken place in the North Sea). After

visiting American, English, and French YMCA officials in Britain and France, the General Secretary traveled to Geneva

in June. He met with World's Committee members and International Red Cross representatives. Most importantly, he attended

a three-day conference on POW relief, attended by WPA secretaries from all of the belligerent nations. Mott was so

impressed with the need for and the opportunity of this work that he cabled New York for twenty additional supervising

secretaries to expand the current WPA force. He estimated that at least sixty-five men were needed for war prison relief

work alone.12

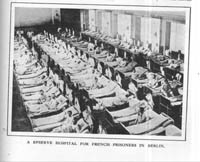

Mott then proceeded to Germany via Basel. The General Secretary stopped at Carlsruhe, where he met with Prince Max, and

continued on to Darmstadt. There he visited the prison camp for French POW's and a cemetery. He then moved on to Berlin

for a five-day visit. He observed the terrible casualties suffered by men who had fought at Verdun. Accepting a personal

invitation from Ambassador Gerard, Mott lunched at the embassy with Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and made

calls at the Ministry of War. In his invitation to the General Secretary, the U.S. ambassador called the American YMCA's

WPA work "the best and most novel work of the war." Gerard reemphasized the importance of POW relief work. It had mollified

a great deal of the hatred the German public had taken at American neutrality violations. Mott also visited several prison

camps near the German capital. He gave a special address at Ruhleben on June 2, accompanied by Gerard. The General Secretary

also took the opportunity to meet with numerous American, Dutch, and German Association officials, including Harte,

Hibbard, Hall, Hermann Rutgers, Theophil Mann, Niedermeyer, Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze, Julius Richter, and Karl Axenfeld.

Finishing his work in Berlin, Mott departed for Vienna to talk with Austrian officials.13

Mott then proceeded to Germany via Basel. The General Secretary stopped at Carlsruhe, where he met with Prince Max, and

continued on to Darmstadt. There he visited the prison camp for French POW's and a cemetery. He then moved on to Berlin

for a five-day visit. He observed the terrible casualties suffered by men who had fought at Verdun. Accepting a personal

invitation from Ambassador Gerard, Mott lunched at the embassy with Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and made

calls at the Ministry of War. In his invitation to the General Secretary, the U.S. ambassador called the American YMCA's

WPA work "the best and most novel work of the war." Gerard reemphasized the importance of POW relief work. It had mollified

a great deal of the hatred the German public had taken at American neutrality violations. Mott also visited several prison

camps near the German capital. He gave a special address at Ruhleben on June 2, accompanied by Gerard. The General Secretary

also took the opportunity to meet with numerous American, Dutch, and German Association officials, including Harte,

Hibbard, Hall, Hermann Rutgers, Theophil Mann, Niedermeyer, Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze, Julius Richter, and Karl Axenfeld.

Finishing his work in Berlin, Mott departed for Vienna to talk with Austrian officials.13

After meeting with Austrian officials in the imperial capital and Hungarian officials in Budapest, Mott returned to

Berlin. During this trip, the General Secretary observed first-hand the tragic sight of a trainload of Allied prisoners

en route to prison camps. Mott conferred further with Harte and Hoffman at his hotel about future WPA work. He also

lunched at the U.S. Embassy a second time, and entertained ten "war workers" at a dinner.

After meeting with Austrian officials in the imperial capital and Hungarian officials in Budapest, Mott returned to

Berlin. During this trip, the General Secretary observed first-hand the tragic sight of a trainload of Allied prisoners

en route to prison camps. Mott conferred further with Harte and Hoffman at his hotel about future WPA work. He also

lunched at the U.S. Embassy a second time, and entertained ten "war workers" at a dinner.

The General Secretary practiced his diplomatic skills by calling at the Danish and Chinese embassies. Before leaving

for Copenhagen, Mott had discussions with Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow. He eventually traveled to Stockholm,

Petrograd, and Moscow before returning to the United States in August 1916. The General Secretary would never forget

this trip. While visiting a military hospital in Germany, he asked a surgeon to explain the effects of modern warfare.

He then walked through endless wards, observing the results of shrapnel, shellfire, bayonets, swords, lances, and

artillery concussions, as well as the victims of tetanus, gas gangrene, and liquid fire. He almost passed out from

witnessing the horrors these unfortunates endured.14

The General Secretary practiced his diplomatic skills by calling at the Danish and Chinese embassies. Before leaving

for Copenhagen, Mott had discussions with Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow. He eventually traveled to Stockholm,

Petrograd, and Moscow before returning to the United States in August 1916. The General Secretary would never forget

this trip. While visiting a military hospital in Germany, he asked a surgeon to explain the effects of modern warfare.

He then walked through endless wards, observing the results of shrapnel, shellfire, bayonets, swords, lances, and

artillery concussions, as well as the victims of tetanus, gas gangrene, and liquid fire. He almost passed out from

witnessing the horrors these unfortunates endured.14

Mott arrived in New York on August 9 on the Norwegian steamer S.S. Oscar II from Copenhagen, accompanied by

Harte, who had taken several weeks' vacation. Mott reported that he had visited prison camps in all of the belligerent

European countries, and claimed that the reports of poor treatment of POWs were greatly exaggerated. Prisoners received

virtually the

Mott arrived in New York on August 9 on the Norwegian steamer S.S. Oscar II from Copenhagen, accompanied by

Harte, who had taken several weeks' vacation. Mott reported that he had visited prison camps in all of the belligerent

European countries, and claimed that the reports of poor treatment of POWs were greatly exaggerated. Prisoners received

virtually the

same food and care as the soldiers of their captors' armies. Mott believed that everything possible was being done

for the comfort and health of the war prisoners. He told the press that the American YMCA had forty-five secretaries

serving 1.75 million Allied POWs in Germany, 1.5 million Central Power prisoners in Russia, and one million Allied POWs

in Austria-Hungary, as well as additional Central Power prisoners in France, Italy, and Britain. Thousands more prisoners

arrived at prison camps across Europe on a weekly basis, and Mott stated that the YMCA was doing its best to provide

relief services to these unfortunate men.15

same food and care as the soldiers of their captors' armies. Mott believed that everything possible was being done

for the comfort and health of the war prisoners. He told the press that the American YMCA had forty-five secretaries

serving 1.75 million Allied POWs in Germany, 1.5 million Central Power prisoners in Russia, and one million Allied POWs

in Austria-Hungary, as well as additional Central Power prisoners in France, Italy, and Britain. Thousands more prisoners

arrived at prison camps across Europe on a weekly basis, and Mott stated that the YMCA was doing its best to provide

relief services to these unfortunate men.15

Expanding WPA Operations in Germany

15

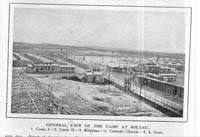

By the early months of 1916, it had become clear to Hoffman that a more effective means of implementing WPA operations

was necessary. Several major obstacles limited POW relief work in Germany. First, Hoffman recognized that the construction

of huts in German prison camps led to considerable inefficiency. While their construction represented an important mental

and physical diversion for POWs, and became the social center of camp life once completed, these halls were expensive to

construct and were a major drain on the Association's budget. In addition, valuable time was lost negotiating permission

from individual camp commandants and obtaining permits from the proper authorities. Finally, the supply of building

materials was limited, since the German economy was focused on war production.

By the early months of 1916, it had become clear to Hoffman that a more effective means of implementing WPA operations

was necessary. Several major obstacles limited POW relief work in Germany. First, Hoffman recognized that the construction

of huts in German prison camps led to considerable inefficiency. While their construction represented an important mental

and physical diversion for POWs, and became the social center of camp life once completed, these halls were expensive to

construct and were a major drain on the Association's budget. In addition, valuable time was lost negotiating permission

from individual camp commandants and obtaining permits from the proper authorities. Finally, the supply of building

materials was limited, since the German economy was focused on war production.

Second, and more importantly, under the German-YMCA Agreement of 1916, based on the Principle of Reciprocity,

twenty-five neutral secretaries were permitted to conduct relief work in prison camps in Central Power countries.

Because Harte had negotiated access to Austro-Hungarian prison camps for twelve American secretaries with Viennese

officials, only thirteen could conduct operations in Germany. These thirteen workers had to cover 150 main prison

camps (Stammlager) over twenty-four Army Corps districts, which necessarily limited the amount of time and

quality contact they could spend with Allied prisoners. Although WPA operations were also supported by German YMCA

volunteers, DCSV secretaries, and neutral clergymen with access to prison camps, the bulk of WPA service fell to

experienced American secretaries.16

Second, and more importantly, under the German-YMCA Agreement of 1916, based on the Principle of Reciprocity,

twenty-five neutral secretaries were permitted to conduct relief work in prison camps in Central Power countries.

Because Harte had negotiated access to Austro-Hungarian prison camps for twelve American secretaries with Viennese

officials, only thirteen could conduct operations in Germany. These thirteen workers had to cover 150 main prison

camps (Stammlager) over twenty-four Army Corps districts, which necessarily limited the amount of time and

quality contact they could spend with Allied prisoners. Although WPA operations were also supported by German YMCA

volunteers, DCSV secretaries, and neutral clergymen with access to prison camps, the bulk of WPA service fell to

experienced American secretaries.16

When visiting prison camps, WPA secretaries ran into infrastructure problems. In large prisons, the Germans segregated

the POWs into smaller compounds according to a model known as the "divided camp system." Prisoners were not permitted

to cross the wire to enter other sections of the prison camp. Through this system, camp authorities could exercise the

same kind of control as in a small prison camp, but were able to operate efficiently through economies of scale and

larger infrastructure.

When visiting prison camps, WPA secretaries ran into infrastructure problems. In large prisons, the Germans segregated

the POWs into smaller compounds according to a model known as the "divided camp system." Prisoners were not permitted

to cross the wire to enter other sections of the prison camp. Through this system, camp authorities could exercise the

same kind of control as in a small prison camp, but were able to operate efficiently through economies of scale and

larger infrastructure.

When Sprunger encountered this system at Giessen, he was quickly frustrated in his work. Because POWs could not move

between sections, he would have had to organize and equip a separate Association for each compound. This would have

been a tremendous drain on his time and the YMCA's resources. Over time, Sprunger was able to develop a rapport with

the camp commandant, and he finally persuaded the German authorities to allow YMCA committee heads to work in all parts

of the camp. This permission allowed Sprunger to develop one Association that could serve the entire camp population.

William Lawall tried a different approach in his first prison camp assignment. To gain the confidence of the POWs, he

voluntarily became a prisoner by moving into the camp. The advantage to living in the prison was that the American

secretary was able to ascertain the needs of these men and work with them as a compatriot. The more serious drawback

was that the YMCA simply lacked the manpower to permit Red Triangle workers to live in prison camps. A more efficient

system of providing welfare relief was needed.17

When Sprunger encountered this system at Giessen, he was quickly frustrated in his work. Because POWs could not move

between sections, he would have had to organize and equip a separate Association for each compound. This would have

been a tremendous drain on his time and the YMCA's resources. Over time, Sprunger was able to develop a rapport with

the camp commandant, and he finally persuaded the German authorities to allow YMCA committee heads to work in all parts

of the camp. This permission allowed Sprunger to develop one Association that could serve the entire camp population.

William Lawall tried a different approach in his first prison camp assignment. To gain the confidence of the POWs, he

voluntarily became a prisoner by moving into the camp. The advantage to living in the prison was that the American

secretary was able to ascertain the needs of these men and work with them as a compatriot. The more serious drawback

was that the YMCA simply lacked the manpower to permit Red Triangle workers to live in prison camps. A more efficient

system of providing welfare relief was needed.17

As a result, Hoffman instituted the policy of "touch and go" to maximize contact and improve the efficiency of service

for war prisoners. American field secretaries entered prison camps and concentrated on organizing a camp Association,

supervised by a managing committee. This task was easier among British POWs, since many of these men had belonged to

YMCAs at home and were already aware of the purpose and goals of the organization. But Catholic and Orthodox prisoners

were often suspicious of the objectives of a Protestant welfare agency. In addition to the president, vice

president, secretary, and treasurer, the field secretary organized the managing body with functional committees

including religion, education, music, sports, welfare, entertainment, and other important activities. Once the

managing committee was selected, the field secretary then provided equipment (musical instruments, athletic equipment,

theatrical costumes and props, books, tools, religious articles, and other items), supplied by WPA Headquarters in Berlin,

so that the POW Association could begin operations. The Red Triangle worker trained the YMCA leaders in the camp, and they

worked together to get operations underway. The vision behind the program was that the prisoners would operate a

self-help welfare organization with funding, equipment, supplies, and supervision provided by the American YMCA. With a

successful Association program up and running, the field secretary then moved on to another prison camp to repeat this

process.18

As a result, Hoffman instituted the policy of "touch and go" to maximize contact and improve the efficiency of service

for war prisoners. American field secretaries entered prison camps and concentrated on organizing a camp Association,

supervised by a managing committee. This task was easier among British POWs, since many of these men had belonged to

YMCAs at home and were already aware of the purpose and goals of the organization. But Catholic and Orthodox prisoners

were often suspicious of the objectives of a Protestant welfare agency. In addition to the president, vice

president, secretary, and treasurer, the field secretary organized the managing body with functional committees

including religion, education, music, sports, welfare, entertainment, and other important activities. Once the

managing committee was selected, the field secretary then provided equipment (musical instruments, athletic equipment,

theatrical costumes and props, books, tools, religious articles, and other items), supplied by WPA Headquarters in Berlin,

so that the POW Association could begin operations. The Red Triangle worker trained the YMCA leaders in the camp, and they

worked together to get operations underway. The vision behind the program was that the prisoners would operate a

self-help welfare organization with funding, equipment, supplies, and supervision provided by the American YMCA. With a

successful Association program up and running, the field secretary then moved on to another prison camp to repeat this

process.18

Established prison Associations kept in contact with the YMCA in two ways. The camp leaders could write to the WPA

headquarters and request additional equipment and supplies as needed. More importantly, a YMCA secretary would

visit periodically to review operations, drop off supplies, and introduce new programs and activities. This "touch and

go" policy allowed a small number of Association secretaries to visit a large number of prison camps in a relatively

short period of time. This broadcast approach also served to publicize the Association's WPA program. As the Germans

transferred POWs between camps, those men who had received YMCA relief pressed to have similar services established at

their new camps. The WPA concept spread like wildfire as camp officials invited field secretaries to visit their facilities.

Because the newly arrived prisoners were already aware of the YMCA program, secretaries found their work in establishing

a welfare program much easier.

Established prison Associations kept in contact with the YMCA in two ways. The camp leaders could write to the WPA

headquarters and request additional equipment and supplies as needed. More importantly, a YMCA secretary would

visit periodically to review operations, drop off supplies, and introduce new programs and activities. This "touch and

go" policy allowed a small number of Association secretaries to visit a large number of prison camps in a relatively

short period of time. This broadcast approach also served to publicize the Association's WPA program. As the Germans

transferred POWs between camps, those men who had received YMCA relief pressed to have similar services established at

their new camps. The WPA concept spread like wildfire as camp officials invited field secretaries to visit their facilities.

Because the newly arrived prisoners were already aware of the YMCA program, secretaries found their work in establishing

a welfare program much easier.

Field visitation became especially important as the Germans began to utilize POW labor to maintain the national economy.

Instead of allowing enlisted prisoners to languish unproductively in prison camps, where they were a drain on the empire's resources,

the Germans assigned POWs to labor detachments (Arbeitskommandos) and sent them to work in factories, quarries,

forests, mines, and fields. These work parties ranged in size from two to two thousand men, and were scattered across

Germany. Field secretaries could still visit these POWs, but it was a far more difficult process. German officials

maintained the relief system in the main camps by exempting YMCA committee leaders from labor detachment assignments.

Thus they could maintain welfare operations, especially for men still idle in the camps or those who were

wounded.19

Field visitation became especially important as the Germans began to utilize POW labor to maintain the national economy.

Instead of allowing enlisted prisoners to languish unproductively in prison camps, where they were a drain on the empire's resources,

the Germans assigned POWs to labor detachments (Arbeitskommandos) and sent them to work in factories, quarries,

forests, mines, and fields. These work parties ranged in size from two to two thousand men, and were scattered across

Germany. Field secretaries could still visit these POWs, but it was a far more difficult process. German officials

maintained the relief system in the main camps by exempting YMCA committee leaders from labor detachment assignments.

Thus they could maintain welfare operations, especially for men still idle in the camps or those who were

wounded.19

Hoffman assigned secretaries to one to three Army Corps districts to conduct field operations as they arrived. By traveling

between camps, Red Triangle workers strove to visit each camp in their region once or twice a month. As a result, a secretary

could visit anywhere from twenty-five to forty camps in a four week period, depending on the area assigned and the number of organized

Associations within those camps. Between 8 July and 11 August 1917, one WPA field secretary conducted the following visits:

Hoffman assigned secretaries to one to three Army Corps districts to conduct field operations as they arrived. By traveling

between camps, Red Triangle workers strove to visit each camp in their region once or twice a month. As a result, a secretary

could visit anywhere from twenty-five to forty camps in a four week period, depending on the area assigned and the number of organized

Associations within those camps. Between 8 July and 11 August 1917, one WPA field secretary conducted the following visits:

| July 8 | Altdamm, Pomerania, Prussia (II Army Corps) |

| July 10 | Sagan, Brandenburg, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| Sprottau, Brandenburg, Prussia (V Army Corps) | |

| July 11 | Neuhammer, Silesia, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| July 12 | Lauban, Silesia, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| July 13 | Reisen, Posen, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| July 16 | Czersk, West Prussia, Prussia (XVII Army Corps) |

| July 17 | Hammerstein, West Prussia, Prussia (XVII Army Corps) |

| July 18 | Stargard, Pomerania, Prussia (II Army Corps) |

| July 19 | Güstrow, Mecklenburg (IX Army Corps) |

| July 20 | Augustabad, Mecklenburg (IX Army Corps) |

| July 21 | Stralsund-Danholm, Pomerania, Prussia (II Army Corps) |

| July 22 | Stralkowo, Posen, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| July 23 | Skalmierschütz, Posen, Prussia (V Army Corps) |

| July 27 | Neisse, Silesia, Prussia (VI Army Corps) |

| Lamsdorf, Silesia, Prussia (VI Army Corps) | |

| July 28 | Gnadenfrei, Silesia, Prussia (VI Army Corps) |

| July 30 | Schneidemühl, West Prussia, Prussia (II Army Corps) |

| July 31 | Arys, East Prussia, Prussia (XX Army Corps) |

| August 1 | Preussisch Holland, East Prussia (XX Army Corps) |

| August 2 | Mewe, West Prussia, Prussia (XVII Army Corps) |

| August 3 | Danzig-Troyl, West Prussia, Prussia (XVII Army Corps) |

| August 8 | Parchim, Mecklenburg (IX Army Corps) |

| August 9 | Bad Stuer, Mecklenburg (IX Army Corps) |

| August 11 | Fürstenberg, Brandenburg, Prussia (III Army Corps) |

This field secretary covered a tremendous territory, which included five provinces in Prussia and Mecklenburg, or six

Army Corps districts (the II, V, VI, IX, XVII, and XX Army Corps).

This field secretary covered a tremendous territory, which included five provinces in Prussia and Mecklenburg, or six

Army Corps districts (the II, V, VI, IX, XVII, and XX Army Corps).

While most secretaries did not have to cover as extensive an area, this indicates the amount of traveling most

Red Triangle workers undertook to serve war prisoners.20

While most secretaries did not have to cover as extensive an area, this indicates the amount of traveling most

Red Triangle workers undertook to serve war prisoners.20

Another field secretary visited prison camps 108 times over a four-month period between September and December 1916. The prisons that this worker ministered to included:

| Camp | Number of Visits |

|---|---|

| Cottbus-Sielow | 27 |

| Döberitz | 13 |

| Dyrotz | 12 |

| Berlin Lazerette | 10 |

| Cottbus-Merzdorf | 7 |

| Ruhleben | 6 |

| Frankfurt-an-der-Oder | 6 |

| Guben | 4 |

| Cüstrin-Fort Gorgast | 4 |

| Münchberg | 3 |

| Havelberg | 3 |

| Crossen-an-der-Oder | 3 |

| Cüstrin-Fort Zorndorf | 2 |

| Halbe | 2 |

| Brandenburg | 2 |

| Blankenburg | 2 |

| Beeskow | 1 |

| Berger Damm | 1 |

This field secretary operated solely in Brandenburg, visiting prison camps under the jurisdiction of the III Army Corps in Berlin. On average, this worker worked in twenty-seven different camps during the course of a month, or almost one a day.21

By early fall 1916, nine American secretaries worked in Germany under the direction of Hoffman. Seven men served as

field secretaries, visiting prison camps and promoting Association activities. Two additional secretaries (E. O. Jacob

and J. S. Kennard) arrived in Germany during the summer of 1916 to conduct field operations. They joined Hoffman, Lawall,

Carl T. Michel, J. Gustav White, J. E. Wehner (who arrived in April 1916), and Claus Olandt (Sprunger had to leave Germany

early in the year because he contracted influenza, and Lawall's assignment would end on 1 December 1916). Two more American

secretaries arrived in September 1916 (Crawford Wheeler and Alfred Lowry, Jr.), followed by three more in November

(Arthur Siebens, Lewis W. Dunn, and Louis E. Wolferz). They were joined by three German YMCA secretaries assigned to American WPA

work: Reverend G. Schrenk (between June 1915 and January 1916), Johann Grote, and Reverend Theophil Mann. The American

YMCA had constructed halls in ten prison camps, and the German Army had assigned barracks for Association use in six

additional prisons.

By early fall 1916, nine American secretaries worked in Germany under the direction of Hoffman. Seven men served as

field secretaries, visiting prison camps and promoting Association activities. Two additional secretaries (E. O. Jacob

and J. S. Kennard) arrived in Germany during the summer of 1916 to conduct field operations. They joined Hoffman, Lawall,

Carl T. Michel, J. Gustav White, J. E. Wehner (who arrived in April 1916), and Claus Olandt (Sprunger had to leave Germany

early in the year because he contracted influenza, and Lawall's assignment would end on 1 December 1916). Two more American

secretaries arrived in September 1916 (Crawford Wheeler and Alfred Lowry, Jr.), followed by three more in November

(Arthur Siebens, Lewis W. Dunn, and Louis E. Wolferz). They were joined by three German YMCA secretaries assigned to American WPA

work: Reverend G. Schrenk (between June 1915 and January 1916), Johann Grote, and Reverend Theophil Mann. The American

YMCA had constructed halls in ten prison camps, and the German Army had assigned barracks for Association use in six

additional prisons.

The WPA field secretaries visited and established Associations in another seventy prison camps. As a result, the YMCA had

relief workers conducting welfare operations in approximately 60 percent of the prison camps in Germany. The percentage

of prisoners affected was even greater, since the secretaries focused their activities on the most populous camps. The

Association also established contact with the most of the remaining camps by correspondence, working with these camps'

welfare committees.

The WPA field secretaries visited and established Associations in another seventy prison camps. As a result, the YMCA had

relief workers conducting welfare operations in approximately 60 percent of the prison camps in Germany. The percentage

of prisoners affected was even greater, since the secretaries focused their activities on the most populous camps. The

Association also established contact with the most of the remaining camps by correspondence, working with these camps'

welfare committees.

The WPA office in Berlin supported these activities, dispatching musical instruments, books, tools, sports equipment,

educational supplies, entertainment equipment, theatrical props, religious paraphernalia, and a wide range of needed

goods. The office served as an Allied POW information bureau, a financial processing center for funds for POWs, and a

correspondence office to provide reports to other national WPA committees, the German government, and foreign embassies.

Hoffman made arrangements with Deutsche Bank to transfer YMCA funds for German POWs in Russia, which as the most efficient

way to send money to prisoners on the Eastern Front. The YMCA employed five typists and stenographers, as well as a censor

who inspected books destined for prison camps. In addition, during times of special pressure, the office staff was assisted

by German women who volunteered their services.22

The WPA office in Berlin supported these activities, dispatching musical instruments, books, tools, sports equipment,

educational supplies, entertainment equipment, theatrical props, religious paraphernalia, and a wide range of needed

goods. The office served as an Allied POW information bureau, a financial processing center for funds for POWs, and a

correspondence office to provide reports to other national WPA committees, the German government, and foreign embassies.

Hoffman made arrangements with Deutsche Bank to transfer YMCA funds for German POWs in Russia, which as the most efficient

way to send money to prisoners on the Eastern Front. The YMCA employed five typists and stenographers, as well as a censor

who inspected books destined for prison camps. In addition, during times of special pressure, the office staff was assisted

by German women who volunteered their services.22

Conclusion

Though the American YMCA characterized its activities as non-political, humanitarian welfare service to POWs, in

practice the Association had to deal with political issues which affected war prisoners. The YMCA secretary usually

lacked any official status, and therefore provided social assistance purely at the pleasure of the host government.

While Harte's shuttle diplomacy opened prison camps to American secretaries, the creation of WPA organizations

established the infrastructure for Red Triangle workers to work with captor governments to provide relief services

for war prisoners. By 1916, the WPA operated on three levels: the World's Alliance of YMCAs at the international level;

on the national level through national YMCA committees; and at the individual level through secretarial work in the

camps.

Though the American YMCA characterized its activities as non-political, humanitarian welfare service to POWs, in

practice the Association had to deal with political issues which affected war prisoners. The YMCA secretary usually

lacked any official status, and therefore provided social assistance purely at the pleasure of the host government.

While Harte's shuttle diplomacy opened prison camps to American secretaries, the creation of WPA organizations

established the infrastructure for Red Triangle workers to work with captor governments to provide relief services

for war prisoners. By 1916, the WPA operated on three levels: the World's Alliance of YMCAs at the international level;

on the national level through national YMCA committees; and at the individual level through secretarial work in the

camps.

The World's Committee in Geneva was the global coordinating body for POW relief work. Since most national Associations

participated in this organization, the World's Alliance stood above reproach in terms of political bias. At the beginning

of the war, the American YMCA acknowledged the extensive experience of the World's Committee in previous relief operations

in Europe and assumed that this body would lead the YMCA through the conflict as a global organization. Mott directed

Hibbard to work closely with Christian Phildius in January 1915, since the "World's Committee is the body to unify and

lead all this great work in Europe and our sole desire in America is to do everything in our power to serve you

[Phildius] and strengthen your hands in this work."23

The World's Committee in Geneva was the global coordinating body for POW relief work. Since most national Associations

participated in this organization, the World's Alliance stood above reproach in terms of political bias. At the beginning

of the war, the American YMCA acknowledged the extensive experience of the World's Committee in previous relief operations

in Europe and assumed that this body would lead the YMCA through the conflict as a global organization. Mott directed

Hibbard to work closely with Christian Phildius in January 1915, since the "World's Committee is the body to unify and

lead all this great work in Europe and our sole desire in America is to do everything in our power to serve you

[Phildius] and strengthen your hands in this work."23

Yet as Harte recorded his diplomatic successes, Phildius achieved only minimal gains. Therefore, the American YMCA

assumed a greater role in the direction of the WPA. The World's Committee increasingly became an umbrella organization

that channeled American resources to specific areas of operations. Although the American YMCA began its POW mission as

an instrument of the

Yet as Harte recorded his diplomatic successes, Phildius achieved only minimal gains. Therefore, the American YMCA

assumed a greater role in the direction of the WPA. The World's Committee increasingly became an umbrella organization

that channeled American resources to specific areas of operations. Although the American YMCA began its POW mission as

an instrument of the

World's Committee, by May 1916 the New York organization noted the Geneva body's limitations, stating that American

secretaries "worked through it [the World's Committee] whenever possible." As POW work gathered momentum, the primary

role that fell to the World's Committee was recruiting neutral European secretaries to augment POW relief services

after the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany. Even then, after American YMCA WPA operations were curtailed in Central Europe,

the World's Committee depended heavily on American financial support.24

World's Committee, by May 1916 the New York organization noted the Geneva body's limitations, stating that American

secretaries "worked through it [the World's Committee] whenever possible." As POW work gathered momentum, the primary

role that fell to the World's Committee was recruiting neutral European secretaries to augment POW relief services

after the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany. Even then, after American YMCA WPA operations were curtailed in Central Europe,

the World's Committee depended heavily on American financial support.24

The strength of the WPA organization was concentrated at the national level in each belligerent country. The American

YMCA strove to establish WPA committees as the primary organ to supervise POW relief. The composition and power of each

committee varied considerably, but most were organized under the jurisdiction of the national YMCA, and their membership

included influential patrons, government officials, diplomatic representatives, and the Senior American Secretary assigned

to that country. It was important to organize the WPA under the supervision of the national YMCAs, since it gave belligerent

governments a degree of control over a neutral social welfare organization. Government officials associated with the WPA

worked with neutral Association secretaries, which extended a semi-official status to WPA committees. More importantly,

these national WPA committees assisted neutral embassies to fulfill their POW inspection responsibilities. National WPA

committees could better assist neutral embassies to provide prisoner information, distribute supplies, improve mail and

parcel services, and allocate funds to prisoners. The WPA committees of different nations also coordinated and

disseminated information regarding POW relief activities, which further promoted the Principle of Reciprocity.25

The strength of the WPA organization was concentrated at the national level in each belligerent country. The American

YMCA strove to establish WPA committees as the primary organ to supervise POW relief. The composition and power of each

committee varied considerably, but most were organized under the jurisdiction of the national YMCA, and their membership

included influential patrons, government officials, diplomatic representatives, and the Senior American Secretary assigned

to that country. It was important to organize the WPA under the supervision of the national YMCAs, since it gave belligerent

governments a degree of control over a neutral social welfare organization. Government officials associated with the WPA

worked with neutral Association secretaries, which extended a semi-official status to WPA committees. More importantly,

these national WPA committees assisted neutral embassies to fulfill their POW inspection responsibilities. National WPA

committees could better assist neutral embassies to provide prisoner information, distribute supplies, improve mail and

parcel services, and allocate funds to prisoners. The WPA committees of different nations also coordinated and

disseminated information regarding POW relief activities, which further promoted the Principle of Reciprocity.25

The American WPA secretary was the direct Association contact with the individual prisoner of war. Due to the limited number of neutral secretaries available for WPA service and the immense areas that they had to cover, secretaries operated under the "Principle of Visitation." Once a secretary gained access to a prison camp, he immediately organized the inmates, usually along the lines of a College Association (the type most familiar to American secretaries). The prisoners elected a general camp committee, which in turn organized several sub-committees by function. These functional committees varied greatly between prison camps, but most adopted a combination of working groups which included welfare, library and reading room, school, arts, music, theater, cinematograph and gramophone, athletic and games, wood-carving and handwork, Christmas festivities, and religious committees. The secretary also acquired a special building to house welfare operations and the equipment to implement the Association's "Four-fold" Program. Once a camp Association was firmly established, the WPA field secretary moved on to the next prison facility. The secretary would return to established camp Associations on a periodic basis, to check up on operations and provide supplies and new equipment. The objective of the "Principle of Visitation" was to establish self-sustaining organizations among the prison inmates. The bulk of the manpower for social welfare operations was provided by the POWs themselves, which permitted field secretaries to cover far larger areas and minister to a greater number of prisoners than assignment to a single camp would have allowed.

Notes:

Note 1: Executive of the World's Committee of YMCAs, "World's Committee of Young Men's Christian Associations, Plenary Meeting of 1920 at Geneva: Report of the Executive for the Period July 1914 to June 1920," The Sphere 2:3 (1921): 197; and Olin D. Wannamaker, For the Six Million Prisoners: The Welfare Work of the YMCA in the Prison Camps of Ten Nations during World War I (September 1921): 119-20. back

Note 2: Wannamaker, Six Million, 120. back

Note 3: Ibid., 121. back

Note 4: The official title of the resulting organization was the German Committee for the Assistance of Prisoners of War of the Young Men's Christian Associations. As the number of Allied POWs continued to grow in Germany, and increasing numbers of men and resources had to be assigned to the Ministry of War's Prisoner of War Department, Friedrich and his staff advanced in rank. By the end of the war, Friedrich had been promoted from colonel to the rank of major-general, while Bauer became a lieutenant-colonel. "Report of the Meeting of the 8th April 1916 in the War Ministry in Berlin," circa April 1916, 1-3. General Report, circa March 1917, 1. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid YMCA, 1914-1915; POW Camps in Germany and France; War Guilt Question." Section 43: "Germany." Folder X391.2 (43): "War Prisoners' Aid in Germany, 1914-1918." World's Alliance of YMCAs Archives, Geneva; Conrad Hoffman, Jr., In the Prison Camps of Germany: A Narrative of "Y" Service among Prisoners of War (New York: Association Press, 1920), 84-85; William Howard Taft, Frederick Harris, Frederic Houston Kent, and William J. Newlin, eds. Service with Fighting Men: An Account of the Work of the American Young Men's Christian Association in the World War, 2 vols. (New York: Association Press, 1922), 2:295; J. Scott Keltie and M. Epstein, eds. The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1915 (London: Macmillan and Company, 1915), 995; and Wannamaker, Six Million, 132. back

Note 5: "Report of the Meeting of the 8th April 1916 in the War Ministry in Berlin," circa April 1916, 1-3. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid YMCA, 1914-1915; POW Camps in Germany and France; War Guilt Question." Section 43: "Germany." Folder X391.2 (43): "War Prisoners' Aid in Germany, 1914-1918." World's Alliance of YMCAs Archives, Geneva. back

Note 6: "Report of the Meeting of 8th April 1916 in the War Ministry in Berlin," circa April 1916, 1-3. General Report, no date, 1-28. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid YMCA, 1914-1915; POW Camps in Germany and France; War Guilt Question." Section 43: "Germany." Folder X391.2 (43): "War Prisoners' Aid in Germany, 1914-1918." World's Alliance of YMCA Archives, Geneva, Switzerland; Archibald C. Harte, "Notes on YMCA Conference, Saturday and Sunday, April 8th and 9th, 1916, Berlin, A. C. Harte Presiding," 9 April 1916, 1-9. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid YMCA, 1914-1915; POW Camps in Germany and France; War Guilt Question." Section 43: "Germany." Folder: "War Prisoners' Aid in Germany: Miscellaneous." World's Alliance of YMCAs Archives, Geneva; Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 84-85; Taft, Harris, Kent, and Newlin, Service with Fighting Men, 2:295; and Wannamaker, Six Million, 132-33. back

Note 7: Wannamaker, Six Million, 120. back

Note 8: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 86-87. back

Note 9: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 88. back

Note 10: Ibid. back

Note 11: "Young Men's Christian Association, Prisoners of War Department: Items of Progress and Interest, May 1st, 1916," 1 May 1916, 1-2. Box X673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN. back

Note 12: International Committee of Young Men's Christian Associations, "Summary of Minutes of Regular Monthly Meetings of the International Committee of the Young Men's Christian Associations," 15 May 1916 and 6 June 1916, New York, 2 and 3. International Committee, Monthly Meeting Minutes, 1909-1916. Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN; C. Howard Hopkins, John R. Mott, 1865-1955: A Biography: 20th Century Ecumenical Statesman (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1979), 463-65; and Wannamaker, Six Million, 122-23. back

Note 13: James W. Gerard, "From the American Ambassador, Berlin," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 July 1916): 3; James W. Gerard to John R. Mott, 10 May 1916, 1. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box X673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder E: "Prisoners of War, YMCA Work for Germany." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN; J. Davidson Ketchum, Ruhleben: A Prison Camp Society (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965), 324-25; and Hopkins, John R. Mott, 465. back

Note 14: Hopkins, John R. Mott, 466-67. back

Note 15: "Prison Camp Captives Exceed 5,000,000 Men: American, Who Saw All of Them, Says Germany Has the Most and Russia Next: All Being Well Treated: Given the Same Food and Care That Armies of Respective Countries Receive," 10 August 1916. Armed Services Records Box AS-20. Box 673.6: "Reports, Clippings, Publications, 1915-1921: World War #1: Prisoners of War." Folder A: "Prisoners of War: Their Treatment." ." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN. back

Note 16: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 65-66. back

Note 17: James E. Sprunger, "Notes from Camps Visited by J. E. Sprunger," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (15 April 1916): 45; and William H. Lawall, "In Prison, Ye Visited Me," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 July 1916): 46. back

Note 18: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 65-66 and 74. back

Note 19: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 65-66; and James E. Sprunger, "Notes from Camps Visited by J. E. Sprunger," 45-46. back

Note 20: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 74; and Taft, Harris, Kent, and Newlin, Service with Fighting Men, 2:294. back

Note 21: Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 75. back

Note 22: James E. Sprunger, "Notes from Camps Visited by J. E. Sprunger," 46; Carl T. Michel, "Extracts from Letters of Three of the New Secretaries," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 July 1916): 45; Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 79; Conrad Hoffman to Thomas C. Hall, no date, 1-2. General Report, circa March 1917, 1-2. World's Alliance Box X391.2: "War Prisoners' Aid YMCA, 1914-1915; POW Camps in Germany and France; War Guilt Question." Section 43: "Germany." Folder X391.2 (43): "War Prisoners' Aid in Germany, 1914-1918." World's Alliance of YMCAs Archives, Geneva; Archibald C. Harte, "With the Prisoners of War," in In the Camps, Trenches, and Prisons of Asia, Africa, and Europe (Oxford: Frederick Hall, Printer to the University, 1916), 36. Armed Services Box AS-20. Box X673.6: "Reports: 1916-1921: World War #1: Allied Armies and Prisoners of War." Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN; and Wannamaker, Six Million, 139-41. back

Note 23: John R. Mott to Christian Phildius, 12 January 1915, New York, 1. John R. Mott Papers, Box 70, Folder 1279, Yale School of Divinity, New Haven, CT. back

Note 24: International Committee, Report of the International Committee of the Young Men's Christian Associations to the Thirty-Ninth International Convention at Cleveland, Ohio, May 12-16, 1916 (New York: Association Press, 1916), 83. back

Note 25: Archibald C. Harte, "War Prisoners' Aid," 12 July 1918. John R. Mott Papers, Box 38, Folder 702, Yale School of Divinity, New Haven, CT; Christian Phildius to John R. Mott, 20 September 1915, Geneva, 1. John R. Mott Papers, Box 70, Folder 1279, Yale School of Divinity, New Haven, CT; "Russia: Prisoners of War," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 1 (31 January 1916): 43-45; Edgar MacNaughten, "Austria-Hungary: For Prisoners of War," For the Millions of Men Now Under Arms 2 (1 November 1916): 33-35; and Hoffman, In the Prison Camps of Germany, 84-85. back