Chapter 18

Countering the Bolshevik Threat: Repatriation and American YMCA Expansion into Eastern Europe

1

By the summer of 1919, American officials expected the imminent repatriation of Russian POWs from Germany. The

Allies supported the White Russian armies and had committed their military forces to occupying North Russia and

Siberia. General Anton Ivanovich Denikin was preparing a major summer offensive to regain the Ukraine, and

General Nicholas Yudenitch would launch an attack on Petrograd in the fall of 1919. While the Polish frontier

and the Danube River-the natural routes of prisoner exchange-were closed to traffic, American relief organizations

planned the repatriation process through Baltic ports. In May 1919, the American Red Cross sent commissions to

Lithuania and Estonia to prepare for these operations.

By the summer of 1919, American officials expected the imminent repatriation of Russian POWs from Germany. The

Allies supported the White Russian armies and had committed their military forces to occupying North Russia and

Siberia. General Anton Ivanovich Denikin was preparing a major summer offensive to regain the Ukraine, and

General Nicholas Yudenitch would launch an attack on Petrograd in the fall of 1919. While the Polish frontier

and the Danube River-the natural routes of prisoner exchange-were closed to traffic, American relief organizations

planned the repatriation process through Baltic ports. In May 1919, the American Red Cross sent commissions to

Lithuania and Estonia to prepare for these operations.

After shipping relief supplies and personnel to these countries, the Red Cross set up clearing stations to process

Russian prisoners from Germany. Over twelve thousand Russians passed through Lithuania in May 1919, but the

organization acknowledged that they were a "mere drop in the bucket." Red Cross officials worked with the Inter-Allied

Commission to facilitate this Baltic exodus. An additional twenty-six thousand Russian POWs traveled through Estonia within the

next few months. In addition, the Allies developed a Hamburg-to-Odessa shipping route to transport Russian prisoners

to southern Russia. By the end of the summer, the Allies had transported fifty thousand prisoners on the long voyage to the

Black Sea.

After shipping relief supplies and personnel to these countries, the Red Cross set up clearing stations to process

Russian prisoners from Germany. Over twelve thousand Russians passed through Lithuania in May 1919, but the

organization acknowledged that they were a "mere drop in the bucket." Red Cross officials worked with the Inter-Allied

Commission to facilitate this Baltic exodus. An additional twenty-six thousand Russian POWs traveled through Estonia within the

next few months. In addition, the Allies developed a Hamburg-to-Odessa shipping route to transport Russian prisoners

to southern Russia. By the end of the summer, the Allies had transported fifty thousand prisoners on the long voyage to the

Black Sea.

The American YMCA followed the lead of the Red Cross and set up operations in Narva, Estonia during the fall of

1919. Two American secretaries organized a clearing station for Russian prisoners heading home from Germany, and

for Central Power POWs en route to Germany or the former Hapsburg dominions. Both the Baltic and Black Sea routes

were inadequate, however, for the hundreds of thousands of prisoners who had to be repatriated. By 30 June 1919,

the American Red Cross planned to reduce repatriation operations in the Baltic because officials expected the

imminent opening of the Polish frontier and the Danube River. The prospect of a White Russian victory in the

Russian Civil War was thought to be so likely that the American Red Cross expected the remainder of Germany's

Russian POWs to return home before the winter of 1919-1920.1

The American YMCA followed the lead of the Red Cross and set up operations in Narva, Estonia during the fall of

1919. Two American secretaries organized a clearing station for Russian prisoners heading home from Germany, and

for Central Power POWs en route to Germany or the former Hapsburg dominions. Both the Baltic and Black Sea routes

were inadequate, however, for the hundreds of thousands of prisoners who had to be repatriated. By 30 June 1919,

the American Red Cross planned to reduce repatriation operations in the Baltic because officials expected the

imminent opening of the Polish frontier and the Danube River. The prospect of a White Russian victory in the

Russian Civil War was thought to be so likely that the American Red Cross expected the remainder of Germany's

Russian POWs to return home before the winter of 1919-1920.1

The failure of the White Russian leaders to unify under a single command and coordinate their military operations

had an adverse effect on Russian POWs in Germany. Instead of returning home near the end of 1919, the Russians

suffered through another winter in German prison camps. The American YMCA provided services and supplies to

relief committees in the camps during this period. Between 1 November 1918 and 31 October 1919, the International

Committee expended $201,200 on WPA operations in German camps, almost 25 percent of the American YMCA's WPA total

budget for that fiscal year. With few Russian prisoners having been repatriated, the American YMCA tried to provide

some relief over the Christmas holidays. They sent supplies from Paris (the center for American YMCA relief work

for Russian refugees) to German prison camps to help the inmates celebrate the Orthodox Christmas in January 1920.

Donald Lowrie, an American YMCA secretary who had worked in Russia during the war, supervised Association efforts

for Russian prisoners in Germany. He faced a difficult challenge since the majority of these men simply wanted to

return home. Lowrie continued Red Triangle support through education, religious, and recreational work to combat

this "soul-destroying environment." Lowrie distributed Christmas parcels in December 1919, including indoor games

(dominoes, checkers, chess, and halma), mouth organs, and a small amount of money (one hundred to 250 Marks), so that

welfare committees could purchase a Christmas tree, decorations, and small supplies. He also made sure that every

Russian prisoner received a pound of apples, and the YMCA continued to distribute candy, cigarettes, cocoa, and

milk. The Red Triangle supplies were supplemented by parcels from the Norwegian Relief Committee, which included

Russian books.2

The failure of the White Russian leaders to unify under a single command and coordinate their military operations

had an adverse effect on Russian POWs in Germany. Instead of returning home near the end of 1919, the Russians

suffered through another winter in German prison camps. The American YMCA provided services and supplies to

relief committees in the camps during this period. Between 1 November 1918 and 31 October 1919, the International

Committee expended $201,200 on WPA operations in German camps, almost 25 percent of the American YMCA's WPA total

budget for that fiscal year. With few Russian prisoners having been repatriated, the American YMCA tried to provide

some relief over the Christmas holidays. They sent supplies from Paris (the center for American YMCA relief work

for Russian refugees) to German prison camps to help the inmates celebrate the Orthodox Christmas in January 1920.

Donald Lowrie, an American YMCA secretary who had worked in Russia during the war, supervised Association efforts

for Russian prisoners in Germany. He faced a difficult challenge since the majority of these men simply wanted to

return home. Lowrie continued Red Triangle support through education, religious, and recreational work to combat

this "soul-destroying environment." Lowrie distributed Christmas parcels in December 1919, including indoor games

(dominoes, checkers, chess, and halma), mouth organs, and a small amount of money (one hundred to 250 Marks), so that

welfare committees could purchase a Christmas tree, decorations, and small supplies. He also made sure that every

Russian prisoner received a pound of apples, and the YMCA continued to distribute candy, cigarettes, cocoa, and

milk. The Red Triangle supplies were supplemented by parcels from the Norwegian Relief Committee, which included

Russian books.2

The Russian prisoners in Germany were clearly a forgotten lot. While the Allied blockade had been lifted in June

1919 and food exports had resumed to Germany, the Russian POWs found that their rations continued to be meager.

Clothing was in equally short supply. Although the Weimar government and German help committees did all they could

to assist the Russians, their position remained pitiable. By January 1920, over two hundred thousand Russian prisoners still

languished in Germany, and they all harbored hopes of returning home during the summer months. The Russian

prisoners, however, would clearly not be leaving Germany in the foreseeable future, and the American YMCA would

have to reorganize its welfare operations.3

The Russian prisoners in Germany were clearly a forgotten lot. While the Allied blockade had been lifted in June

1919 and food exports had resumed to Germany, the Russian POWs found that their rations continued to be meager.

Clothing was in equally short supply. Although the Weimar government and German help committees did all they could

to assist the Russians, their position remained pitiable. By January 1920, over two hundred thousand Russian prisoners still

languished in Germany, and they all harbored hopes of returning home during the summer months. The Russian

prisoners, however, would clearly not be leaving Germany in the foreseeable future, and the American YMCA would

have to reorganize its welfare operations.3

Establishment of Russian Relief Work in Germany

5

To a large extent, the International Committee had neglected their Russian charges still in Germany. After the

war, the American YMCA developed post-war welfare programs in many Eastern European nations and implemented

pledges made during the conflict. While a general reconciliation with Germany was achieved by 1920 within the World's Alliance, relations

between the American and German Associations remained guarded. The International Committee had focused on providing

welfare services for the victims of the Russian Civil War and helping the Russian Orthodox Church survive the

conflict. Ralph Hollinger, an experienced American YMCA secretary, organized an Association School in Cleveland

to train secretaries for service with Russians before leaving for Eastern Europe in 1919. Early in 1920, Paul B.

Anderson and Joseph J. Somerville, American secretaries with extensive Russian experience, were in London preparing

to return to Russia when they learned of the plight of the Russian prisoners still in Germany. They took immediate

measures to have men sent from Hollinger's school to Germany to assist Lowrie.4

To a large extent, the International Committee had neglected their Russian charges still in Germany. After the

war, the American YMCA developed post-war welfare programs in many Eastern European nations and implemented

pledges made during the conflict. While a general reconciliation with Germany was achieved by 1920 within the World's Alliance, relations

between the American and German Associations remained guarded. The International Committee had focused on providing

welfare services for the victims of the Russian Civil War and helping the Russian Orthodox Church survive the

conflict. Ralph Hollinger, an experienced American YMCA secretary, organized an Association School in Cleveland

to train secretaries for service with Russians before leaving for Eastern Europe in 1919. Early in 1920, Paul B.

Anderson and Joseph J. Somerville, American secretaries with extensive Russian experience, were in London preparing

to return to Russia when they learned of the plight of the Russian prisoners still in Germany. They took immediate

measures to have men sent from Hollinger's school to Germany to assist Lowrie.4

By May 1920, the American YMCA had greatly expanded the scope of its WPA work for Russian prisoners. Anderson

and Somerville joined Lowrie in Germany to expand Association operations. This force was augmented by fifteen

American Rhodes scholars from Oxford University who volunteered to spend their summer in Germany helping the

Russians. The situation in the prison camps had changed radically during the winter months. The Russian POWs

became zealous students after a rumor began that the Soviet government would not accept any POWs who could not

read or write.

By May 1920, the American YMCA had greatly expanded the scope of its WPA work for Russian prisoners. Anderson

and Somerville joined Lowrie in Germany to expand Association operations. This force was augmented by fifteen

American Rhodes scholars from Oxford University who volunteered to spend their summer in Germany helping the

Russians. The situation in the prison camps had changed radically during the winter months. The Russian POWs

became zealous students after a rumor began that the Soviet government would not accept any POWs who could not

read or write.

Russian welfare committees in the prison camps "abolished illiteracy" among these soldiers, who were largely

peasants, and declared that no prisoner would be repatriated who could not pass a literacy test. Anderson helped

the Russians set up schools across Germany. The POWs set up education committees, recruited teachers from the POW

ranks, and the Association obtained scarce Russian textbooks from a variety of sources. The dearth of textbooks

was the primary obstacle, and the YMCA had to import them from the Russian border countries, such as Latvia, Poland,

and Czechoslovakia. Anderson also requested that the Russian Department of the American YMCA publish Russian books

in Berlin. To teach orthography, the Association printed the letters of the Russian alphabet on large sheets of paper.

Teachers could easily tack these sheets to the walls of classrooms and POWs could practice copying the letters in

their notebooks.

Russian welfare committees in the prison camps "abolished illiteracy" among these soldiers, who were largely

peasants, and declared that no prisoner would be repatriated who could not pass a literacy test. Anderson helped

the Russians set up schools across Germany. The POWs set up education committees, recruited teachers from the POW

ranks, and the Association obtained scarce Russian textbooks from a variety of sources. The dearth of textbooks

was the primary obstacle, and the YMCA had to import them from the Russian border countries, such as Latvia, Poland,

and Czechoslovakia. Anderson also requested that the Russian Department of the American YMCA publish Russian books

in Berlin. To teach orthography, the Association printed the letters of the Russian alphabet on large sheets of paper.

Teachers could easily tack these sheets to the walls of classrooms and POWs could practice copying the letters in

their notebooks.

At Bautzen, the Association secretary found only one thousand Russian prisoners. All fifty illiterate POWs in this camp

went to school for three hours every day. To compensate these men for their enforced schooling, the camp commandant

"paid " them five cigarettes a day. The American YMCA provided books to the school at Stargard, which permitted

the camp committee to extend their operations. A similar situation emerged at Parchim.

At Bautzen, the Association secretary found only one thousand Russian prisoners. All fifty illiterate POWs in this camp

went to school for three hours every day. To compensate these men for their enforced schooling, the camp commandant

"paid " them five cigarettes a day. The American YMCA provided books to the school at Stargard, which permitted

the camp committee to extend their operations. A similar situation emerged at Parchim.

The Russian POWs sought to establish an "ideal community," where everyone worked for the good of all. Over three hundred

students volunteered to go to the camp school, which was taught by seven teachers drawn from the POW ranks,

who refused pay for their labors. The poorer pupils helped with the school and worked for free during their

spare time in camp activities such as bookbinding, theater work, or choir participation.

The Russian POWs sought to establish an "ideal community," where everyone worked for the good of all. Over three hundred

students volunteered to go to the camp school, which was taught by seven teachers drawn from the POW ranks,

who refused pay for their labors. The poorer pupils helped with the school and worked for free during their

spare time in camp activities such as bookbinding, theater work, or choir participation.

Proceeds from entertainment performances were used to purchase new books for the library and daily newspapers

for the barracks, reading room, hospital, and prison. Russian camp authorities encouraged educational pursuits

through speeches and propaganda notices. Their mantra was: "If you can read, go to the library and get books;

if you can't, come to school and we will teach you." For more advanced students, the education committees

organized courses in history, geography, mathematics, and languages. By the end of the year, the American secretary

could report that only a very small number of men (less than 15 percent of the POWs) remained illiterate.5

Proceeds from entertainment performances were used to purchase new books for the library and daily newspapers

for the barracks, reading room, hospital, and prison. Russian camp authorities encouraged educational pursuits

through speeches and propaganda notices. Their mantra was: "If you can read, go to the library and get books;

if you can't, come to school and we will teach you." For more advanced students, the education committees

organized courses in history, geography, mathematics, and languages. By the end of the year, the American secretary

could report that only a very small number of men (less than 15 percent of the POWs) remained illiterate.5

At Bautzen, the Association secretary found only one thousand Russian prisoners. All fifty illiterate POWs in this camp went to school for three hours every day. To compensate these men for their enforced schooling, the camp commandant "paid" them five cigarettes a day. The American YMCA provided books to the school at Stargard, which permitted the camp committee to extend their operations. A similar situation emerged at Parchim. The Russian POWs sought to establish an "ideal community," where everyone worked for the good of all. Over 300 students volunteered to go to the camp school, which was taught by seven teachers drawn from the POW ranks, who refused pay for their labors. The poorer pupils helped with the school and worked for free during their spare time in camp activities such as bookbinding, theater work, or choir participation. Proceeds from entertainment performances were used to purchase new books for the library and daily newspapers for the barracks, reading room, hospital, and prison. Russian camp authorities encouraged educational pursuits through speeches and propaganda notices. They embraced the concept: "If you can read, go to the library and get books; if you can't, come to school and we will teach you." For more advanced students, the education committees organized courses in history, geography, mathematics, and languages. By the end of the year, the American secretary could report that only a very small number of men (less than 15 percent of the POWs) remained illiterate.6

But the Russians' enthusiasm exceeded a mere thirst for learning to read and write. The prisoners embraced the

concept that the salvation of Russia lay in the improved knowledge and working ability of its citizens. What

the country desperately needed was an improved level of education throughout the entire population. While there

were strong Bolshevist tendencies among the Russian prisoners in Germany, non-Bolsheviks spoke their thoughts

and held office in the camp committees-all of the prison camps adopted the principle of absolute free speech.

With the success of the Red Army, many POWs accepted the Soviet as their future form of government as a matter

of national patriotism. Given the destruction caused by the First World War and the Russian Civil War, most

Russian prisoners realized that they were not returning to a land of milk and honey. They recognized that "what

Russia needs most was education of all her people, education both general and technical."7

But the Russians' enthusiasm exceeded a mere thirst for learning to read and write. The prisoners embraced the

concept that the salvation of Russia lay in the improved knowledge and working ability of its citizens. What

the country desperately needed was an improved level of education throughout the entire population. While there

were strong Bolshevist tendencies among the Russian prisoners in Germany, non-Bolsheviks spoke their thoughts

and held office in the camp committees-all of the prison camps adopted the principle of absolute free speech.

With the success of the Red Army, many POWs accepted the Soviet as their future form of government as a matter

of national patriotism. Given the destruction caused by the First World War and the Russian Civil War, most

Russian prisoners realized that they were not returning to a land of milk and honey. They recognized that "what

Russia needs most was education of all her people, education both general and technical."7

At this point, political perspectives had shifted radically, both on the part of the Russian prisoners and the

American and British secretaries. While Conrad Hoffman and the Allied authorities exercised primary control

over the Russian POWs, the Association was locked in mortal combat with the Bolsheviks. Maintaining tight

control over Bolshevik activities, the Allies sought to win the hearts and minds of these prisoners, and the

Association believed that it held the upper hand through its Four-fold Program of mental, spiritual, and physical

improvement. With the withdrawal of Allied supervision and the reduction of Association WPA support, the Russian

prisoners found themselves increasingly neglected and isolated. By the summer of 1920, the tide had turned. Most

of the Russian POWs accepted the prediction that the Bolsheviks would emerge triumphant from the Russian Civil

War, and they embraced Marxist ideology. Even the American YMCA realized that access to Russia in the future

would require cooperation with the Soviet government. By refusing to work with the Bolsheviks to develop a

modus vivendi, the Association would lose all of the gains that the organization had made since the beginning

of World War I.8

At this point, political perspectives had shifted radically, both on the part of the Russian prisoners and the

American and British secretaries. While Conrad Hoffman and the Allied authorities exercised primary control

over the Russian POWs, the Association was locked in mortal combat with the Bolsheviks. Maintaining tight

control over Bolshevik activities, the Allies sought to win the hearts and minds of these prisoners, and the

Association believed that it held the upper hand through its Four-fold Program of mental, spiritual, and physical

improvement. With the withdrawal of Allied supervision and the reduction of Association WPA support, the Russian

prisoners found themselves increasingly neglected and isolated. By the summer of 1920, the tide had turned. Most

of the Russian POWs accepted the prediction that the Bolsheviks would emerge triumphant from the Russian Civil

War, and they embraced Marxist ideology. Even the American YMCA realized that access to Russia in the future

would require cooperation with the Soviet government. By refusing to work with the Bolsheviks to develop a

modus vivendi, the Association would lose all of the gains that the organization had made since the beginning

of World War I.8

This new Russian relief movement focused on practical training courses where prisoners could learn new trades and

skills to rebuild and modernize the Russian economy. Prison committees emphasized the value of trade for the

development of the nation rather than for individuals securing a livelihood. One important area of development was

electricity; Russia lacked a national electrical system. At Crossen-an-der-Oder, the Association helped set up the

Technical School of Electricity. The YMCA hired a teacher from Berlin, and the proceeds from the camp's canteen and

cinema shows went to support the school. Anderson pressed the Association to establish another technical school at

Güstrow. The YMCA trained prisoners in a wide variety of fields. Some prisoners learned electrical theory and

application, including the generation and transmission of electrical currents, simpler uses of electric power,

wiring for light and power, telephone installation, and telegraphy. In carpentry, furniture-making, and painting

classes, POWs received training in the use of ordinary carpentry tools, making joints for simple building construction,

furniture-making, and varnishing and painting these products. Other prisoners at Güstrow learned locksmithing,

including opening locks whose keys were lost, lock construction systems, and safety appliances. Since many Russian

prisoners came from rural areas, agricultural classes were also stressed. Prisoners learned about soil culture, crop

rotation, dairying, and farm machinery use. In addition, POWs could receive training in library science and learn how

to set up libraries for village communities. Similar schools were established in Parchim, Stargard, and

Altdamm.9

This new Russian relief movement focused on practical training courses where prisoners could learn new trades and

skills to rebuild and modernize the Russian economy. Prison committees emphasized the value of trade for the

development of the nation rather than for individuals securing a livelihood. One important area of development was

electricity; Russia lacked a national electrical system. At Crossen-an-der-Oder, the Association helped set up the

Technical School of Electricity. The YMCA hired a teacher from Berlin, and the proceeds from the camp's canteen and

cinema shows went to support the school. Anderson pressed the Association to establish another technical school at

Güstrow. The YMCA trained prisoners in a wide variety of fields. Some prisoners learned electrical theory and

application, including the generation and transmission of electrical currents, simpler uses of electric power,

wiring for light and power, telephone installation, and telegraphy. In carpentry, furniture-making, and painting

classes, POWs received training in the use of ordinary carpentry tools, making joints for simple building construction,

furniture-making, and varnishing and painting these products. Other prisoners at Güstrow learned locksmithing,

including opening locks whose keys were lost, lock construction systems, and safety appliances. Since many Russian

prisoners came from rural areas, agricultural classes were also stressed. Prisoners learned about soil culture, crop

rotation, dairying, and farm machinery use. In addition, POWs could receive training in library science and learn how

to set up libraries for village communities. Similar schools were established in Parchim, Stargard, and

Altdamm.9

Anderson realized that the Association was taking on a large project. He developed ties with the Russian Bureau

for War Prisoners to collaborate in setting up technical institutes to train prisoners. With limited resources

in terms of books, instructors, and material, Anderson recognized that the greatest benefits from this training

would only be achieved by limiting the variety of courses offered to POWs and the number of students.

Anderson realized that the Association was taking on a large project. He developed ties with the Russian Bureau

for War Prisoners to collaborate in setting up technical institutes to train prisoners. With limited resources

in terms of books, instructors, and material, Anderson recognized that the greatest benefits from this training

would only be achieved by limiting the variety of courses offered to POWs and the number of students.

By keeping classes small, they could achieve the highest efficiency of instruction, training, and practice.

Anderson believed that by training Russian POWs, the Association would become an effective force in the

reconstruction of the country through the future activities of the men that they trained. These skilled workers

would demonstrate the effectiveness of the Association program, and the Soviet government would be willing to

consider new forms of cooperation in the near future.10

By keeping classes small, they could achieve the highest efficiency of instruction, training, and practice.

Anderson believed that by training Russian POWs, the Association would become an effective force in the

reconstruction of the country through the future activities of the men that they trained. These skilled workers

would demonstrate the effectiveness of the Association program, and the Soviet government would be willing to

consider new forms of cooperation in the near future.10

These WPA secretaries also introduced the same programs and activities to Russian prisoners as had been organized

for POWs during the war. They set up canteens, provided musical instruments for the formation of bands and

orchestras, and organized choirs and theater companies. Probably the most popular entertainment among the Russian

POWs was motion pictures, for which the American YMCA provided projectors and films. The Russian Welfare Committee

at Stargard sent a note of gratitude to the International Committee:

These WPA secretaries also introduced the same programs and activities to Russian prisoners as had been organized

for POWs during the war. They set up canteens, provided musical instruments for the formation of bands and

orchestras, and organized choirs and theater companies. Probably the most popular entertainment among the Russian

POWs was motion pictures, for which the American YMCA provided projectors and films. The Russian Welfare Committee

at Stargard sent a note of gratitude to the International Committee:

Thanks to your services in providing entertainments, and especially the gift of a cinema, our comrades pass their free time for their own good, and every day they are attracted away from harmful pastimes such as drinking and gambling.11

American secretaries had also set up an extensive welfare system for Russian prisoners in southern Germany by July 1920, establishing camp work at Erlangen, Puchheim, Hammelburg, Bayreuth, Ingolstadt, and Nürnberg in Bavaria, and Ulm and Münsingen in Württemberg. By this time, Anderson had set up an Association headquarters for Russian work in Berlin, with the assistance of Trainer P. Miller, which was at full operation by October. The moral welfare of these men remained a high priority for the YMCA secretaries.12

American Relief Operations

15

The YMCA secretaries dispatched to work with Russian prisoners also cooperated with other American relief

organizations working in Germany. American Red Triangle workers noted the terrible economic conditions the

German people faced during the summer of 1920. The lack of fuel, the high cost of foreign raw materials, and

difficulties in finding overseas markets crippled Germany's export industries, which represented 25 percent of

the nation's Gross Natioanl Product before the war. Every German city was crowded with idle men, barefoot women,

and sickly and stunted children. The cinemas were crowded every night, not because of widespread prosperity, but

because the movies were the only place people could get warm. The German government was headed for bankruptcy, as

state printing presses produced one billion new paper Marks each week without increasing the nation's gold

reserves. The Germans were using up their permanent wealth at a rapid pace. They lived in houses they could not

rebuild, wore out furniture and clothing they could not replace, and traveled over roads and railroads that were

steadily deteriorating. In Stettin, the tramway system simply stopped because the company could not maintain fares

that people could afford and simultaneously pay the wages of the system's employees. As a result, workers had to

walk to their jobs, tramway operators became unemployed, and the company's shares lost all value.

The YMCA secretaries dispatched to work with Russian prisoners also cooperated with other American relief

organizations working in Germany. American Red Triangle workers noted the terrible economic conditions the

German people faced during the summer of 1920. The lack of fuel, the high cost of foreign raw materials, and

difficulties in finding overseas markets crippled Germany's export industries, which represented 25 percent of

the nation's Gross Natioanl Product before the war. Every German city was crowded with idle men, barefoot women,

and sickly and stunted children. The cinemas were crowded every night, not because of widespread prosperity, but

because the movies were the only place people could get warm. The German government was headed for bankruptcy, as

state printing presses produced one billion new paper Marks each week without increasing the nation's gold

reserves. The Germans were using up their permanent wealth at a rapid pace. They lived in houses they could not

rebuild, wore out furniture and clothing they could not replace, and traveled over roads and railroads that were

steadily deteriorating. In Stettin, the tramway system simply stopped because the company could not maintain fares

that people could afford and simultaneously pay the wages of the system's employees. As a result, workers had to

walk to their jobs, tramway operators became unemployed, and the company's shares lost all value.

Despite these hardships, most Germans treated American relief workers with the utmost kindness and consideration.

The upper classes were eager to establish a good relationship with the Americans, while the lower classes heard

of the American relief work and showed their appreciation for U.S. welfare efforts. German families in contact

with the AEF found good reason for making the acquaintance of Americans in Germany.

Despite these hardships, most Germans treated American relief workers with the utmost kindness and consideration.

The upper classes were eager to establish a good relationship with the Americans, while the lower classes heard

of the American relief work and showed their appreciation for U.S. welfare efforts. German families in contact

with the AEF found good reason for making the acquaintance of Americans in Germany.

To have been a POW under American control during the war was usually a windfall for the family. Most German

prisoners brought home comforts that the family could not afford, including American tobacco, soap, a U.S.

Army overcoat, wool socks, shirts, and underwear.13

To have been a POW under American control during the war was usually a windfall for the family. Most German

prisoners brought home comforts that the family could not afford, including American tobacco, soap, a U.S.

Army overcoat, wool socks, shirts, and underwear.13

The American YMCA consulted with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and the American Relief Administration (ARA) during these organizations' welfare work in Germany. The first American Quaker delegation (consisting of Jane Addams, Carolena M. Wood, and Dr. Alice Hamilton) crossed the Dutch border into Germany in June 1919 and conducted a survey of conditions. They reported on the terrible impact of the Allied blockade on the health of German children, and they recommended that the AFSC undertake a food distribution program to assist them. German children suffered from a variety of diseases including rickets, mental retardation, dropsy, anemia, skin disease, and especially tuberculosis. Children were often two to three years older than they appeared. During the fall of 1919, Herbert Hoover asked the Quakers to take over American food distribution in Germany. The AFSC accepted the request and sent the first group of eighteen relief workers, under the direction of Alfred G. Scattergood, in January 1920, to initiate food distribution operations. Within six months, the AFSC was feeding approximately eight hundred thousand undernourished children one hot meal a day.

The Quakers set up food distribution operations across Germany, focusing on large cities, particularly Berlin,

Danzig, Stettin, Breslau, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Hamburg, Essen, Cologne, Coblenz, Frankfurt-am-Main, Mainz,

Munich, Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz. The organization set up eight relief districts, with a central office

in each district (Essen, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, Frankfurt-am-Main, Dresden, and Munich). Two or

more American Quaker representatives were assigned to each office-with the exception of Cologne, which was

under the direction of the British Society of Friends-to coordinate and inspect the allocation, transport,

and distribution of supplies; to arrange medical examinations of mothers and children seeking rations; to

organize and direct local volunteer groups; to make periodic reports, inventories, and audits; and to enable

efficient, honest, non-partisan, and friendly implementation of this program. The AFSC was able to set up such

an extensive operation by enlisting German volunteers; over twenty-two thousand Germans supported this great humanitarian

enterprise. The Quakers organized central kitchens and feeding stations in these cities, providing the food and

equipment. Children received white bread and thick, hot soup after they had been selected through a careful

medical examination as the neediest cases.

The Quakers set up food distribution operations across Germany, focusing on large cities, particularly Berlin,

Danzig, Stettin, Breslau, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Hamburg, Essen, Cologne, Coblenz, Frankfurt-am-Main, Mainz,

Munich, Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz. The organization set up eight relief districts, with a central office

in each district (Essen, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, Frankfurt-am-Main, Dresden, and Munich). Two or

more American Quaker representatives were assigned to each office-with the exception of Cologne, which was

under the direction of the British Society of Friends-to coordinate and inspect the allocation, transport,

and distribution of supplies; to arrange medical examinations of mothers and children seeking rations; to

organize and direct local volunteer groups; to make periodic reports, inventories, and audits; and to enable

efficient, honest, non-partisan, and friendly implementation of this program. The AFSC was able to set up such

an extensive operation by enlisting German volunteers; over twenty-two thousand Germans supported this great humanitarian

enterprise. The Quakers organized central kitchens and feeding stations in these cities, providing the food and

equipment. Children received white bread and thick, hot soup after they had been selected through a careful

medical examination as the neediest cases.

The American YMCA secretaries in Germany worked with Robert Yarnall, the leader of the American Quaker Mission

in Germany, although the focus of Red Triangle work remained relief for the Russian prisoners. In New York,

Hoover called a conference in June 1920 to address welfare relief operations in Germany. This meeting included

representatives of the AFSC, the American YMCA, the American Relief Administration, the YWCA, and the Jewish

Joint Distribution Committee. Hoover asked these organizations to cooperate and pool their resources in mutual

assistance. He recommended that they form a new fund-raising organization to finance relief operations. The

representatives agreed and formed the European Relief Council (ERC). Over time, the American Red Cross, the

Federal Council of Churches, the Knights of Columbus, and the National Catholic Welfare Council joined the

ERC. The goal of all of these organizations in extending assistance to Germany was to carry the message of

good will from America and to provide needed assistance to desperate people. This work was of immense value

for the future peace of Central Europe, and marked the first step towards the friendship among nations that

was a prerequisite for the reconstruction of Europe.14

The American YMCA secretaries in Germany worked with Robert Yarnall, the leader of the American Quaker Mission

in Germany, although the focus of Red Triangle work remained relief for the Russian prisoners. In New York,

Hoover called a conference in June 1920 to address welfare relief operations in Germany. This meeting included

representatives of the AFSC, the American YMCA, the American Relief Administration, the YWCA, and the Jewish

Joint Distribution Committee. Hoover asked these organizations to cooperate and pool their resources in mutual

assistance. He recommended that they form a new fund-raising organization to finance relief operations. The

representatives agreed and formed the European Relief Council (ERC). Over time, the American Red Cross, the

Federal Council of Churches, the Knights of Columbus, and the National Catholic Welfare Council joined the

ERC. The goal of all of these organizations in extending assistance to Germany was to carry the message of

good will from America and to provide needed assistance to desperate people. This work was of immense value

for the future peace of Central Europe, and marked the first step towards the friendship among nations that

was a prerequisite for the reconstruction of Europe.14

The Renewed Repatriation of Russian Prisoners in the Summer of 1920

20With the successes of the Red Army and the collapse of the White Armies across Russia during the summer of 1920, there was no longer any reason for the Allies to prevent the Weimar government from repatriating Russian prisoners. The Germans established a Baltic shipping route between Stettin and Narva, Estonia, Riga, Latvia, and Bjoerkö, Finland to transport Russian prisoners from Germany and retrieve German and Dual Monarchy POWs from Russia. While the political constraints on repatriation no longer existed, physical barriers had emerged. Under Annex III of Part VIII, "Reparation," of the Versailles Treaty, most of Germany's merchant marine fleet had been transferred to the Entente nations as replacements for Allied merchant ships and fishing boats sunk during the war. These enforced reparations left very few merchant ships available to transport prisoners between Germany and Estonia. Of the eight ships that the German government could charter to ply the Baltic waters during the summer months of 1920, only one ship was German-owned.15

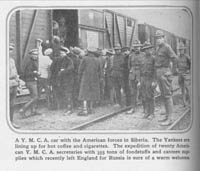

To ease the suffering of the POWs during the repatriation process, the American YMCA assigned secretaries to serve prisoners at Baltic ports and aboard the merchant ships. Lowrie, J. A. V. Davies, G. S. Whitehead, and other American secretaries served on these crowded ships. For example, the 1,500-ton transport, S.S. Regina, carried bunks for 550 men, but the average load was almost eight hundred. Despite the over-crowded situation, living conditions were better than expected. The Germans provided appetizing and adequate food, and the ship's officers made the passengers, both Russians and Central Europeans, as comfortable and contented as possible. The Central Association Office in Berlin provided the YMCA secretaries with ample supplies for the voyage. Red Triangle workers distributed gift packages (Liebesgaben) to all of the prisoners. These parcels included cigarettes, chocolate, writing paper, envelopes, small souvenir maps of the trip, games, and books. For sick and undernourished babies, the secretaries provided condensed milk (many Central Power prisoners imprisoned in Siberia during the war acquired wives and families and brought them home during the repatriation process). For sick Central Power prisoners returning from Russia, the YMCA offered milk, eggs, lemons, and biscuits. The Association also arranged for doctors to accompany the ships, although they had few supplies to minister to the seriously ill. This welfare work was unique, as the American YMCA was the only relief agency working with the repatriates.16

For the Russian prisoners heading back home, these voyages were only the beginning of their long trek. Once on

board ship, they abandoned their shyness and began to play music on their accordions. This eventually expanded

into larger shows, where performers usually included clog dancers, acrobats, readers, opera singers, and makeshift

orchestras.

For the Russian prisoners heading back home, these voyages were only the beginning of their long trek. Once on

board ship, they abandoned their shyness and began to play music on their accordions. This eventually expanded

into larger shows, where performers usually included clog dancers, acrobats, readers, opera singers, and makeshift

orchestras.

Men gathered into groups by nationality for evening concerts and vied with each other singing their favorite

national songs. They offered a simple fervent patriotism as they sang their Russian songs. Despite the red bands

they wore on their arms, they carried home loving and kindly hearts.17

Men gathered into groups by nationality for evening concerts and vied with each other singing their favorite

national songs. They offered a simple fervent patriotism as they sang their Russian songs. Despite the red bands

they wore on their arms, they carried home loving and kindly hearts.17

The Central Power prisoners arriving in Stettin from Russia were a somewhat different lot. The Bolshevik government sent home only prisoners that had been certified 60 percent invalid by a special committee; officers were not permitted to leave. Some officers slipped through the examination disguised as enlisted men or insane. Life in much of Russia had been reduced to a state of barter. Prisoners exchanged goods for labor or other goods. Lowrie met POWs who earned forty-two rubles a day for skilled work, but a pound of butter cost 1,300 rubles. It was difficult for these men to survive, but they formed cooperatives where members pooled their resources and food to make ends meet. The Central Power prisoners also varied considerably in nationality. They began the war as German or Austro-Hungarian troops, but they arrived at Stettin as Germans, Austrians, Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Romanians, Yugoslavians, or Italians. In comparison to the Russian prisoners, these men were more alert, better educated, and even more destitute. Since many of these men had lived in Russia for six years, some of them had met Russian women and married. They returned with complete families, and Lowrie reported that one transport he traveled on carried eighty children, including an eight-day old baby. Many of these men were sick, the children were malformed and undernourished, and all bore traces of mental suffering; Davies described one ship that landed 125 insane prisoners in Stettin.18

When these ships docked, the former prisoners were met by German girls carrying flowers and bands playing national songs. The prisoners cheered for the first time in many years. They stumbled down the gangplanks carrying assorted packs filled with their ragged collections of worldly goods. The POWs wore a variety of articles, ranging from German and Austrian uniforms to Russian peasant clothing, all patched. Some wore shoes or homemade sandals, but most were ragged. Nevertheless, they wept at the welcome. Families reunited on the docks: parents and sons, wives and husbands, and even new children or grandchildren. Some parents and wives met every transport, hoping to hear some news about a lost loved one from disembarking prisoners. The YMCA had secretaries meet these transports at their arrival at Stettin. The Americans were invariably asked if the United States was open to these men. With the imposition of tougher immigration laws, the secretaries had to respond that, while the U.S. did not offer them a home at that time, Americans were mindful of their plight and were anxious to help them rebuild Europe.19

25The Germans could not understand the motivation behind the American YMCA's relief effort for prisoners during the repatriation process. The primary principle that drove Red Triangle welfare operations was the organization's basic Christian mission. These prisoners were a forgotten lot, with many significant needs. They had been neglected by the world, their children were undernourished, and most were sick. These forlorn prisoners felt a new hope when they met an Association secretary who renewed their spirits and gave them a reason to look forward to the future:

The generous sympathy and compassion, the realization that we are not entirely forgotten in this foreign land, help many a despairing one to new hope, and to bring a bright beam of sunshine into their existence.20

By providing comforts and demonstrating a Christian concern, secretaries hoped, in some small way, to assuage the

pain these men had endured and to show that they were not completely forgotten. As one returning POW said, "Your

service is indicative of the spirit of true and genuine religion, it strengthens the hope in me for a time of

fraternalism and Christian love among men."21 These were

the first concrete post-war steps towards international reconciliation and the reconstruction of Central and

Eastern Europe.22

By providing comforts and demonstrating a Christian concern, secretaries hoped, in some small way, to assuage the

pain these men had endured and to show that they were not completely forgotten. As one returning POW said, "Your

service is indicative of the spirit of true and genuine religion, it strengthens the hope in me for a time of

fraternalism and Christian love among men."21 These were

the first concrete post-war steps towards international reconciliation and the reconstruction of Central and

Eastern Europe.22

The Russo-Polish War of 1920 and German Prison Camps

The number of Russian POWs in Germany suddenly grew again during the fall of 1920 as the result of the Russo-Polish War. On 25 April 1920 the Polish Army invaded the Ukraine to seize control of this territory from the Bolsheviks. The Poles had formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader, General Simon Petliura, and sought to take advantage of Bolshevik diversions on other fronts. The Polish Army swarmed east, and by May 7 the Poles had captured Kiev. The American YMCA sent war work secretaries to support the Polish Army, and it appeared that the Poles had won a stunning victory. The Red Army, however, spent this time concentrating its forces for a counter-offensive in the Ukraine. In early June 1920, the Bolshevik armies attacked, and the Poles staged a desperate defense. The Polish lines broke, and the Bolsheviks recaptured Kiev on June 11, and seized Vilna on July 15. The Poles retreated west, fighting a delaying action. The Red Army captured Pinsk, Grodno, and Bialystok, and a Polish collapse appeared imminent. But this delaying action bought Marshal Josef Pilsudski time to reorganize his forces (with the support of the French, under General Maxim Weygand) and establish a defense line between Lvov, in the southeast, running northwest to Plotsk. By August 14, the Bolsheviks were on the outskirts of the Polish capital, and the Battle of Warsaw began. After several days of heavy Bolshevik attack, the Poles launched a counter-offensive east of Warsaw. Through the "Miracle of the Vistula," Pilsudski split the Bolshevik armies, forcing the Soviets to fall back and relinquish their Polish conquests. With new threats from the White Russians under General Peter Wrangel from Yalta, the Bolsheviks decided to sign an armistice with the Poles on 12 October 1920 to end the fighting on their western front.23

With the sudden Polish counter-offensive in August 1920, Red Army units in northern Poland found themselves cut

off from retreat. They faced two alternatives: annihilation by the Poles or internment in East Prussia. Given

these choices, the Bolsheviks crossed the German border and surrendered. Approximately forty thousand Red Army prisoners

became the "guests" of the German government. These new Soviet internees represented a new threat to German

security. They were feared by the German population because of their reported atrocities during the Russian Civil

War, and by the Weimar government for their potential incitement of radicals. As a result, the Germans established

an air-tight guard over these men to prevent them from having any contact with civilians. The Soviet representatives

in Germany supported this decision because they did not want these men exposed to Allied agents. Even Red Triangle

secretaries found it difficult to enter prison camps with Bolshevik prisoners.24

With the sudden Polish counter-offensive in August 1920, Red Army units in northern Poland found themselves cut

off from retreat. They faced two alternatives: annihilation by the Poles or internment in East Prussia. Given

these choices, the Bolsheviks crossed the German border and surrendered. Approximately forty thousand Red Army prisoners

became the "guests" of the German government. These new Soviet internees represented a new threat to German

security. They were feared by the German population because of their reported atrocities during the Russian Civil

War, and by the Weimar government for their potential incitement of radicals. As a result, the Germans established

an air-tight guard over these men to prevent them from having any contact with civilians. The Soviet representatives

in Germany supported this decision because they did not want these men exposed to Allied agents. Even Red Triangle

secretaries found it difficult to enter prison camps with Bolshevik prisoners.24

The interminable state of war had a terrible impact on many Red Army prisoners, and the Soviet Bureau in Berlin

recognized how much the American YMCA had assisted Russian POWs during World War I. Anderson visited the prison

camp for the new Russian internees at Arys in late August 1920 and recognized the need for the immediate

implementation of relief work for these men. He contacted John R. Mott in early September requesting additional

aid to begin operations. The American willingness to extend assistance and the dire condition of many of these internees

resulted in the Bolsheviks permitting another American YMCA secretary, D. M. Amaker, to inspect Red Army internees

in the fall of 1920. Amaker's mission was to study how Association efforts might be most profitably directed for

the welfare of Red Army prisoners; to observe the morale and physical condition of the prisoners and take stock of

their willingness to organize schools and participate in sports, music, or theatricals; to ascertain the needs of

sick Red Army prisoners; and to look for other possible areas of usefulness. He was accompanied by two Russians: Dr.

Jossilewski, a physician who was not sympathetic to Bolshevik economic theories but was deeply interested in the

welfare of Russian POWs; and Colonel Duisburg, a former tsarist officer who had converted to the Bolshevik cause.

He was interned with his troops in East Prussia, but was elected by the interned officers as their representative

to the Soviet Bureau in Berlin. By permitting Amaker to travel with Soviet representatives, the German prison camp

commandants could see that the Bolshevik authorities personally vouched for YMCA work.25

The interminable state of war had a terrible impact on many Red Army prisoners, and the Soviet Bureau in Berlin

recognized how much the American YMCA had assisted Russian POWs during World War I. Anderson visited the prison

camp for the new Russian internees at Arys in late August 1920 and recognized the need for the immediate

implementation of relief work for these men. He contacted John R. Mott in early September requesting additional

aid to begin operations. The American willingness to extend assistance and the dire condition of many of these internees

resulted in the Bolsheviks permitting another American YMCA secretary, D. M. Amaker, to inspect Red Army internees

in the fall of 1920. Amaker's mission was to study how Association efforts might be most profitably directed for

the welfare of Red Army prisoners; to observe the morale and physical condition of the prisoners and take stock of

their willingness to organize schools and participate in sports, music, or theatricals; to ascertain the needs of

sick Red Army prisoners; and to look for other possible areas of usefulness. He was accompanied by two Russians: Dr.

Jossilewski, a physician who was not sympathetic to Bolshevik economic theories but was deeply interested in the

welfare of Russian POWs; and Colonel Duisburg, a former tsarist officer who had converted to the Bolshevik cause.

He was interned with his troops in East Prussia, but was elected by the interned officers as their representative

to the Soviet Bureau in Berlin. By permitting Amaker to travel with Soviet representatives, the German prison camp

commandants could see that the Bolshevik authorities personally vouched for YMCA work.25

This delegation traveled across Germany, inspecting the prison camps that held Red Army detainees. They began

with visits to prison camps in the vicinity of Berlin before heading south. In Bayreuth, in Bavaria, Amaker found hundreds

of suffering prisoners. They had marched hundreds of miles on empty stomachs and were in desperate need of clean

clothing, baths, and good food. Most of these men were exhausted and apathetic.

This delegation traveled across Germany, inspecting the prison camps that held Red Army detainees. They began

with visits to prison camps in the vicinity of Berlin before heading south. In Bayreuth, in Bavaria, Amaker found hundreds

of suffering prisoners. They had marched hundreds of miles on empty stomachs and were in desperate need of clean

clothing, baths, and good food. Most of these men were exhausted and apathetic.

In the German prison, the Russians were disinfected and bathed and then received a thick soup. The German hospital

barracks were not prepared to receive the Red Army prisoners, and the Russians felt bitterness against the Germans

for not offering them better treatment. The delegates proceeded to Erlangen, where Red Army and German

military patients received the same treatment and were integrated into the same wards. These interned soldiers

raved about their good treatment and begged to remain where they were.26

In the German prison, the Russians were disinfected and bathed and then received a thick soup. The German hospital

barracks were not prepared to receive the Red Army prisoners, and the Russians felt bitterness against the Germans

for not offering them better treatment. The delegates proceeded to Erlangen, where Red Army and German

military patients received the same treatment and were integrated into the same wards. These interned soldiers

raved about their good treatment and begged to remain where they were.26

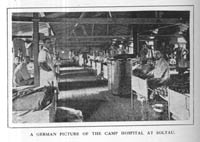

The delegates then traveled north, visiting Red Army enlisted prisoners at Soltau and Parchim, plus the officers'

camp at Falkenburger Moor. Conditions in the prison camps in northern Germany were superior to those in the south.

In these prisons, the morale of the Red Army troops was much better. They chafed at the restrictions the Germans

placed on their liberty of movement, and they pointed out that they were interned soldiers, not prisoners of war.

They considered themselves to be the "guests" of the German government, and they expected the best of everything.

Upon closer reflection, many Red Army detainees acknowledged that they were glad to stay in Germany for a while,

with a roof over their heads, a place to lie down, and at least one good meal a day. Amaker was especially

surprised by the clothing the Red Army internees wore: many of these men wore American Army coats, shirts,

breeches, wrapped puttees, and overseas caps (the Russians had taken them from Polish POWs, corpses, or from

captured warehouses). Both Red Army officers and enlisted men were delighted at the prospect of receiving Red

Triangle welfare support. They welcomed the gifts of athletic equipment, including soccer balls, basketballs,

handballs, as well as indoor games, such as checkers and chess. Amaker also arranged for the YMCA to send special

food items to Red Army prisoners in German military hospitals as well as other gifts. He opened the door for

American YMCA assistance to all two hundred thousand Russian prisoners still incarcerated in Germany as of December

1920.27

The delegates then traveled north, visiting Red Army enlisted prisoners at Soltau and Parchim, plus the officers'

camp at Falkenburger Moor. Conditions in the prison camps in northern Germany were superior to those in the south.

In these prisons, the morale of the Red Army troops was much better. They chafed at the restrictions the Germans

placed on their liberty of movement, and they pointed out that they were interned soldiers, not prisoners of war.

They considered themselves to be the "guests" of the German government, and they expected the best of everything.

Upon closer reflection, many Red Army detainees acknowledged that they were glad to stay in Germany for a while,

with a roof over their heads, a place to lie down, and at least one good meal a day. Amaker was especially

surprised by the clothing the Red Army internees wore: many of these men wore American Army coats, shirts,

breeches, wrapped puttees, and overseas caps (the Russians had taken them from Polish POWs, corpses, or from

captured warehouses). Both Red Army officers and enlisted men were delighted at the prospect of receiving Red

Triangle welfare support. They welcomed the gifts of athletic equipment, including soccer balls, basketballs,

handballs, as well as indoor games, such as checkers and chess. Amaker also arranged for the YMCA to send special

food items to Red Army prisoners in German military hospitals as well as other gifts. He opened the door for

American YMCA assistance to all two hundred thousand Russian prisoners still incarcerated in Germany as of December

1920.27

By November 1920, the American YMCA had established an extensive welfare program for Russian prisoners across

Germany. Bryant R. Ryall supervised Russian operations from Berlin, which included relief work for war

prisoners, internees, and refugees. The Association set up technical schools and libraries across Germany for

Russian refugees who had fled the horrors of the Russian Civil War. For POWs and internees, the Association

assigned six American Red Triangle workers to work as field secretaries in thirty-nine prison camps. M. V.

Arnold worked in northern Germany, assigned to Pomerania (Altdamm and Stargard) and Mecklenburg (Güstrow,

and Parchim). J. N. Engle served eight prison camps in central and eastern Germany.

By November 1920, the American YMCA had established an extensive welfare program for Russian prisoners across

Germany. Bryant R. Ryall supervised Russian operations from Berlin, which included relief work for war

prisoners, internees, and refugees. The Association set up technical schools and libraries across Germany for

Russian refugees who had fled the horrors of the Russian Civil War. For POWs and internees, the Association

assigned six American Red Triangle workers to work as field secretaries in thirty-nine prison camps. M. V.

Arnold worked in northern Germany, assigned to Pomerania (Altdamm and Stargard) and Mecklenburg (Güstrow,

and Parchim). J. N. Engle served eight prison camps in central and eastern Germany.

He conducted operations in Brandenburg (Crossen-an-der-Oder, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Cottbus, Guben, and

Müncheberg), Silesia (Sagan and Neuhammer), and Saxony (Bautzen). Charles L. Moore was assigned the

largest number of prison camps, serving nine facilities in Prussian Saxony, Anhalt, and Hesse-Nassau in central

Germany. Moore worked in Prussian Saxony (Merseburg, Quedlinburg, Magdeburg, Gardelegen, and Salzwedel),

Anhalt (Zerbst), Hesse-Nassau (Cassel), and Saxony (Chemnitz and Zwickau). Joseph J. Somerville served

Russians in northwestern Germany, working in Westphalia (Senne, Minden, Ströhen Moore, and Lichtenhorst)

and Hannover (Hameln, Celle, and Lüneburg). V. C. Hart, also assigned to northwestern Germany, focused his

work exclusively on prisons in Hannover (Soltau, Havelburg, Ahlen Falkenberger Moore, and Königsmoor). In

southern Germany, Howard E. Merrill conducted WPA operations in Bavaria (Würzburg, Bayreuth, Erlangen,

Puchheim, and Hammelburg), Württemberg (Ulm and Münsingen), and Brandenburg (Fürstenfeldbrück).

Together, they served 158,220 Russian prisoners and internees in German prison camps, plus 3,787 Russians

convalescing in hospitals. The American secretaries also provided services to the sixteen boatloads of Russians

that departed Germany for Estonia during November 1920.28

He conducted operations in Brandenburg (Crossen-an-der-Oder, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, Cottbus, Guben, and

Müncheberg), Silesia (Sagan and Neuhammer), and Saxony (Bautzen). Charles L. Moore was assigned the

largest number of prison camps, serving nine facilities in Prussian Saxony, Anhalt, and Hesse-Nassau in central

Germany. Moore worked in Prussian Saxony (Merseburg, Quedlinburg, Magdeburg, Gardelegen, and Salzwedel),

Anhalt (Zerbst), Hesse-Nassau (Cassel), and Saxony (Chemnitz and Zwickau). Joseph J. Somerville served

Russians in northwestern Germany, working in Westphalia (Senne, Minden, Ströhen Moore, and Lichtenhorst)

and Hannover (Hameln, Celle, and Lüneburg). V. C. Hart, also assigned to northwestern Germany, focused his

work exclusively on prisons in Hannover (Soltau, Havelburg, Ahlen Falkenberger Moore, and Königsmoor). In

southern Germany, Howard E. Merrill conducted WPA operations in Bavaria (Würzburg, Bayreuth, Erlangen,

Puchheim, and Hammelburg), Württemberg (Ulm and Münsingen), and Brandenburg (Fürstenfeldbrück).

Together, they served 158,220 Russian prisoners and internees in German prison camps, plus 3,787 Russians

convalescing in hospitals. The American secretaries also provided services to the sixteen boatloads of Russians

that departed Germany for Estonia during November 1920.28

The same six American secretaries maintained relief operations at these prison camps during December 1920.

During this period, approximately forty thousand Russian POWs left Germany on twenty-three different voyages.

The same six American secretaries maintained relief operations at these prison camps during December 1920.

During this period, approximately forty thousand Russian POWs left Germany on twenty-three different voyages.

The number of Russian prisoners fell to 116,476, although the number of Russians in German prison hospitals

increased by twelve cases. At this time, Amos A. Ebersole, Charles Seitz, and Herbert S. Gott expanded

Association services for Russian refugees in Eastern Europe. In particular, they worked to institute relief

services in Estonia to meet the growing tide of Russian refugees in the Baltic countries.29

The number of Russian prisoners fell to 116,476, although the number of Russians in German prison hospitals

increased by twelve cases. At this time, Amos A. Ebersole, Charles Seitz, and Herbert S. Gott expanded

Association services for Russian refugees in Eastern Europe. In particular, they worked to institute relief

services in Estonia to meet the growing tide of Russian refugees in the Baltic countries.29

The onset of winter slowed down the repatriation process in January 1921. The freezing of Baltic ports hindered

shipborne traffic. While twenty-two transport voyages occurred during the month, the number of Russian POWs in

Germany only declined by just under fourteen thousand men, to 102,681.

The onset of winter slowed down the repatriation process in January 1921. The freezing of Baltic ports hindered

shipborne traffic. While twenty-two transport voyages occurred during the month, the number of Russian POWs in

Germany only declined by just under fourteen thousand men, to 102,681.

The good news was that over seven hundred Russians left German hospitals, leaving 3,001 Russian patients. Enough Russian

POWs had left the country so that the German government could close the facilities at Merseberg and Zwickau, and

the government announced that an additional seven camps would be shut down that month. During the long winter

months, the six American field secretaries maintained religious, social, and education work. They made a major

effort to make sure that the prisoners and internees enjoyed a cheerful Orthodox Christmas. The Association

trade schools remained operating at full throttle, and Wünsdorf became a model school for refugees.

The good news was that over seven hundred Russians left German hospitals, leaving 3,001 Russian patients. Enough Russian

POWs had left the country so that the German government could close the facilities at Merseberg and Zwickau, and

the government announced that an additional seven camps would be shut down that month. During the long winter

months, the six American field secretaries maintained religious, social, and education work. They made a major

effort to make sure that the prisoners and internees enjoyed a cheerful Orthodox Christmas. The Association

trade schools remained operating at full throttle, and Wünsdorf became a model school for refugees.

To assist the poorer elements of the German population, YMCA secretaries helped the American Quakers operate

soup kitchens. In addition, American Baptists had taken an intense interest in fighting Bolshevism through

evangelical Christian work. Twenty-five Baptist churches pooled their resources in early 1921 to support four

evangelists working in German prison camps. They were locked in mortal combat with Bolshevik agitators, who

opposed the Baptist evangelists with all of their power. The Christian-Bolshevik struggle for the hearts and

minds of Russian prisoners was far from over.30

To assist the poorer elements of the German population, YMCA secretaries helped the American Quakers operate

soup kitchens. In addition, American Baptists had taken an intense interest in fighting Bolshevism through

evangelical Christian work. Twenty-five Baptist churches pooled their resources in early 1921 to support four

evangelists working in German prison camps. They were locked in mortal combat with Bolshevik agitators, who

opposed the Baptist evangelists with all of their power. The Christian-Bolshevik struggle for the hearts and

minds of Russian prisoners was far from over.30

The repatriation process resumed in earnest in February 1921. Nineteen shiploads of Russian prisoners carried

over thirty thousand men during the month, leaving 69,745 POWs and internees, while the number of hospital patients fell

to 2,389.

The repatriation process resumed in earnest in February 1921. Nineteen shiploads of Russian prisoners carried

over thirty thousand men during the month, leaving 69,745 POWs and internees, while the number of hospital patients fell

to 2,389.

Prison camps closed in Mecklenburg (Parchim), Saxony (Bautzen and Chemnitz), Silesia (Neuhammer), Brandenburg

(Cottbus, Müncheberg, and Fürstenfeldbruck), Prussian Saxony (Merseburg), Westphalia (Ströhen

Moore), Württemberg (Ulm and Münsingen), and Bavaria (Würzburg, Puchheim, and Hammelburg). Fourteen

prison camps closed operations across Germany, which allowed the American YMCA to reassign Arnold and Merrill to other

duties. They were replaced by C. C. Hatfield, who took over operations in the few camps left open in Mecklenburg,

Pomerania, and Bavaria.31.

Prison camps closed in Mecklenburg (Parchim), Saxony (Bautzen and Chemnitz), Silesia (Neuhammer), Brandenburg

(Cottbus, Müncheberg, and Fürstenfeldbruck), Prussian Saxony (Merseburg), Westphalia (Ströhen

Moore), Württemberg (Ulm and Münsingen), and Bavaria (Würzburg, Puchheim, and Hammelburg). Fourteen

prison camps closed operations across Germany, which allowed the American YMCA to reassign Arnold and Merrill to other

duties. They were replaced by C. C. Hatfield, who took over operations in the few camps left open in Mecklenburg,

Pomerania, and Bavaria.31.

A major political breakthrough in Russian POW repatriation from Germany occurred in March 1921, when the Polish

and Bolshevik governments signed the Treaty of Riga. This agreement officially ended the war between Poland and

Russia and allowed the Germans to repatriate Red Army internees. Five American field secretaries under Ryall's

direction served the Russians in twenty-two prison camps, but the number of prisoners departing Germany during

March was low.

A major political breakthrough in Russian POW repatriation from Germany occurred in March 1921, when the Polish

and Bolshevik governments signed the Treaty of Riga. This agreement officially ended the war between Poland and

Russia and allowed the Germans to repatriate Red Army internees. Five American field secretaries under Ryall's

direction served the Russians in twenty-two prison camps, but the number of prisoners departing Germany during

March was low.

Only fourteen thousand Russians headed east, leaving a total of 55,468 POW's and internees in prisons and another 2,217

patients in German hospitals. With the advent of spring and the thawing of Baltic ports, the number of departing

Russians increased to over sixteen thousand. By the end of April 1921, only 39,318 POWs remained in Germany (plus 2,037

hospital patients). Somerville also left Germany, leaving Hart, Moore, Hatfield, and Engle as the Association

field secretaries. F. Hill Turner supervised the technical school at Wünsdorf for Russian refugees.32

Only fourteen thousand Russians headed east, leaving a total of 55,468 POW's and internees in prisons and another 2,217

patients in German hospitals. With the advent of spring and the thawing of Baltic ports, the number of departing

Russians increased to over sixteen thousand. By the end of April 1921, only 39,318 POWs remained in Germany (plus 2,037

hospital patients). Somerville also left Germany, leaving Hart, Moore, Hatfield, and Engle as the Association

field secretaries. F. Hill Turner supervised the technical school at Wünsdorf for Russian refugees.32

With the swift repatriation of Russian POWs and internees back to Russia, the American YMCA again shifted gears.

The Red Triangle secretaries reduced their work for the waning number of prisoners and concentrated on providing

welfare services to Russian refugees who could not return home for political reasons. By November 1921, the

American YMCA had ended all of its work for Russian prisoners of war in Germany and dedicated its resources to

refugee assistance.33

With the swift repatriation of Russian POWs and internees back to Russia, the American YMCA again shifted gears.

The Red Triangle secretaries reduced their work for the waning number of prisoners and concentrated on providing

welfare services to Russian refugees who could not return home for political reasons. By November 1921, the

American YMCA had ended all of its work for Russian prisoners of war in Germany and dedicated its resources to

refugee assistance.33

With Bolshevik victories in the Russian Civil War and the pillars of tsarist society threatened with extinction,

the American YMCA assumed a new role in the post-war world. The Bolsheviks launched the Red Terror, a campaign

to reconstruct Russian society and place it on the path to socialism. Dedicated to atheism and the destruction

of the key institutions of the imperial regime, the Bolsheviks strove to eliminate all vestiges of the Russian

Orthodox Church. Surviving members of the Russian nobility fled the country to save their lives. Even Russian

intellectuals found themselves in conflict with the nation's new social architects. The American YMCA had hoped