Table of Contents

Acknowledgements Introduction

Organization

Chapter Six — Working Men's Party

1Formed in 1829 as one of the nation's first pro-labor political parties, the New York City Working Men's Party (WMP) quickly divided along factional lines as three separate groups—each claiming to truly represent the political face of the city's working men—soon took turns hurling abuse at one another. In the midst of the mudslinging, Thomas Skidmore, the leader of the agrarian faction, published "Rights of Children" in his newspaper, The Friend of Equal Rights. Skidmore noticed that "Paine and others have written in behalf of the rights of men. Miss Wolstoncraft and others in favour of the Rights of Women; but few or none have said any thing in behalf of the rights of Children. Political writers, in their theories, and governments in their practice, have considered them as scarcely having any rights at all."1 After he detailed children's natural right to food, shelter, clothing, and mental and physical education, he contrasted these rights with what philanthropic charity provided them.

Like the vast majority of Working Men, Skidmore was a father and grounded his political ideology in the concerns of fatherhood and ensuring the welfare and prosperity of future generations.2 Just as Chapter Five detailed how skilled working men formed and maintained trade unions in order to combat perceived threats to their family breadwinning, this chapter explores how the WMP attempted to redress potential threats to organized men's obligations as fathers. Far from divorcing the political arena from the domestic arena, Working Men developed a party platform grounded in their household-based masculinity. This chapter argues that competing visions of fatherhood and the question of how best to provide for children guided the formation and activity of the New York Working Men's Party between 1829 and 1831.

First, this chapter briefly narrates the factional drama that consumed both the WMP and those who have studied it. While detailing the machinations of this factional debate is necessary for analyzing the WMP, this process has often overwhelmed attempts to interpret the events of these chaotic few years. This analysis is not concerned with determining whether any of the three factions embodied an "authentic" and "radical" Working Men's (or Workies') agenda.3 Second, this discussion shows that the WMP movement developed through specific gendered terms, demonstrating how issues of household-based masculine identity came to the forefront of this political endeavor. It argues that the three factions embodied three discrete interpretations of what it meant to be a proper working father and that their conflict stemmed from competing visions of how best to govern their children. Third, this chapter examines the party's short life through four of its most important and contentious platform concerns: agrarianism, education, worker morality, and birth control. When one steps back from the day-to-day wrangling of the WMP, a very different picture emerges of the party, one in which the relationship between fathers and children took center stage and accounted for the factional division that eventually led to the WMP's demise.

The Working Men's Party

Related document:

Committee of Fifty Report

The rise and fall of the New York Working Men's Party is an oft-told tale. Its first histories appeared less than a decade after

the party's collapse, and it has been a topic of frequent study and speculation ever since.4 Following a bitterly cold and economically sluggish winter, journeymen artisans met in April 1829 in

reaction to their employers' anticipated move to increase the building trades workday to eleven hours.5 A series of meetings convened a Committee of Fifty which worked to produce a report and plan

of action over the summer, even though the issue of longer workdays seems to have quickly resolved itself. Meanwhile,

Robert Dale Owen, who had moved to New York in June from his father's planned community at New Harmony, followed a summer

of writing in support of the Committee of Fifty with the creation of the "Association for the Protection of Industry and

for the Promotion of National Education."6 Led by printer George Henry Evans

and Dr. Cornelius Blatchly, the Association garnered support for the passage of a state law providing for publicly supported

education.7 The Committee of Fifty finally presented its report at a mass

meeting on October 19, 1829 at Military Hall. Isaac Odell, a journeyman carpenter, chaired the meeting and Robert Dale Owen

served as one of its secretaries.

Mechanic Thomas Skidmore firmly controlled the WMP that emerged from the October 19th meeting. He used the evening to ratify a series of resolutions in support of his agrarian program to distribute property equally among the population.8 Following the meeting and a few subsequent events, the committee hastily selected a slate of candidates for the upcoming state assembly and state senate campaigns. The November election proved a stunning debut for the weeks-old Working Men's Party formed in Skidmore's image. One of its candidates, carpenter Ebenezer Ford, was elected to the Assembly and two other candidates, Skidmore and his close associate Alexander Ming, Sr., each came within fewer than thirty votes of victory. All told, the WMP garnered over 6,000 of the 21,000 votes cast.

After the November election success, factions headed by Robert Dale Owen and Noah Cook moved swiftly to challenge Skidmore's domination of the party. At a large party meeting on December 29 at Military Hall, new operatives shouted down Skidmore's followers and gained control of the party. As a result of the December meeting, the party reemerged with a new seventy-member General Executive Committee in place of the Committee of Fifty. The new structure thoroughly isolated Skidmore's faction, and although he continued to attack each of the other camps, his activities had little effect on either of their electoral fates.

Related document:

Proceedings of WMP Dec. 1829 Meeting

Robert Dale Owen led the first group, which coalesced around his newspapers, the Free Enquirer, co-edited by

Frances "Fanny" Wright, and the Daily Sentinel.9 George Henry Evans,

editor of the Working Man's Advocate, and other supporters of Owen's state guardianship system of education also

played influential roles in this group. Noah Cook and Henry G. Guyon, who chaired the December meeting, headed the third

faction within the WMP. This group gained the endorsement of the Evening Journal after Cook became co-editor, as

well as Cook's own paper, the New-York Reformer, Farmers', Mechanics', and Working Men's Champion, and William

Goodell's evangelical temperance paper, the Genius of Temperance, Philanthropist and People's Advocate. Active

temperance and Christian morality advocates including Guyon, Adoniram Chandler, and Joseph Hoxie also assumed leadership

positions in the Cook faction.10

With Skidmore out of the way, the Owenite and Cookite factions continued a power struggle for control and the name of the Working Men's Party throughout the rest of 1830 and into 1831. With superior numbers, the Cookites eventually assumed control of the General Executive Committee and the party's agenda, most evident in the vote on the education sub-committee's report. The sub-committee produced a majority report which followed Cook's plan for a moderate system of publicly-funded education for all children regardless of wealth and rejected a minority report that followed Owen's more ambitious plan for a state guardianship system. According to Owen's plan, all children, regardless of wealth, would be removed from their families at age two and sent to boarding schools where they would receive equal food, clothes, and education until they matured.

Subsequently, the competing camps held separate nominating conventions prior to the statewide election in November 1830.11 Cookites, allied with the Albany Working Men's Party and other Farmers' and Working Men's groups from upstate, eventually formed a coalition with the Anti-Masonic and National Republican candidates, while Owen's and even Skidmore's faction also landed on the ballot with their own candidates. The 1830 election proved to be a victory for the Democratic Party. Tammany Hall collected about 11,000 votes, with Cook's coalition candidates pulling in just over 7,000 votes. Only 2,200 men supported Owen's slate, while Skidmore's faction mustered just over 100 votes. Some incarnations of the WMP struggled on for another year, but their base of support had evaporated.

10While this overview of the party has been brief, it has pointed out that in a short period, three distinct factions formed within the WMP and split over a list of wide ranging issues, from agrarianism and education to Christian worker morality and birth control. Before examining these concerns in detail, it is useful to contextualize the WMP within a contemporary moment of gendered language and ideology.

Numerous scholars show how Early Republican political culture utilized the language and imagery of masculine and feminine stereotypes to provoke certain responses regarding social order and citizenship. Likewise, ideas about gender informed a variety of political endeavors, not just the American Revolution, or Jefferson's or Jackson's political careers.12 Gendered political discourse took on specific relevance in New York state history at the time of the WMP because of recent changes in who could consider himself as a citizen. The New York Constitutional Convention of 1821 granted near-universal white male suffrage, but it was not until the changes made to the 1828 state constitution that many journeymen and laborers engaged the political system.13 The new franchise was a major topic of discussion and Working Men made clear their support of an egalitarian citizenry, albeit one composed exclusively of white men.14 In this political arena, a discussion about voters became a discussion about idealized white masculinity. In the words of one party newspaper, this issue came to the forefront because, for the first time ever, "every man is a voter" and could contribute to the debate.15 This reality also accounted for some of the animosity expressed by Democratic partisans, who wrote that by "throwing open the polls to every man that walks, we have placed the power in the hands of those who have neither property, talents, nor influence in other circumstances."16 Such attacks followed the WMP throughout its life as detractors accused them of being unworthy to join the public debate about ideal civic masculinity.

Agrarianism

While it is not surprising that Working Men's Party rhetoric contained heavily gendered content, it was unique among contemporary political movements in that it focused so specifically on the issue of fatherhood. It is difficult to argue that fatherhood was more important to Working Men than it was to other political activists, but the persistence of their parental concerns demonstrates their consistent desire to address the perceived threats to their ability to guide the fate of the next generation.17 In the case of the WMP, its activities, members, and platform issues constantly returned to the debate over ideal fatherhood. Although there are numerous examples of Working Men accusing one another of being less than "honorable men," their debates revolved around more than gendered name-calling; they centered on working fathers' obligations and on competing proposals of how working men should act to best fulfill those obligations.18 The shared importance of fatherly concerns, however, did not mean that Working Men agreed on what it meant to be a good father.

Three distinct images of fatherhood emerged among the WMP, each supported by a different faction. Led by Thomas Skidmore, the first camp posited that children had inherent natural rights regardless of their fathers' abilities. Skidmore's proposed program superceded many traditional patriarchal obligations, removing such issues as property inheritance and education from the prerogative of the father in favor of the state. Robert Dale Owen's faction championed the concept that if all children received instruction in how to be rational and just, regardless of their fathers' socioeconomic or cultural circumstances, society would have true democracy. The centerpiece of this plan was Owen's state guardianship system of education that would have removed all children from their families at age two in order to provide equal scholastic opportunity. Noah Cook's followers coalesced around a more traditional patriarchal vision: while they sought improved educational and economic opportunities for their children, they wanted to protect fathers' rights to govern their posterity and create a moral environment as they saw fit. Even though fatherly matters such as property inheritance, education, moral instruction, and birth control certainly inspired and intrigued all Working Men, divisions quickly formed over the specifics of how to address these issues politically.

Thomas Skidmore's model of fatherhood and its relationship to the next generation concerned property inheritance and his design for so-called agrarianism. Skidmore published his agrarian plan in his 400-page disquisition, The Rights of Man to Property!, and a later pamphlet entitled Political Essays, written on behalf of an organization he fronted named the New York Association for the Gratuitous Distribution of Discussion on Political Economy.19 Skidmore did not package his ideas for easy consumption and he did not offer simple answers. Scholars have correctly cited the revolutionary and grandiose nature of Skidmore's plans, even if his proposals did not actually represent many Working Men's point of view.20

15Sean Wilentz has argued that the Skidmore-led Working Men's Party of 1829 thrived because of its ability to use men such as Thomas Paine (whose work was obviously referenced in The Rights of Man to Property!) to claim the legacy of the Revolution and portray themselves as defenders of Republicanism. In this view of the party, Skidmore's eventual failure resulted from his opponents' ability to label him as "an unrepublican, violent fanatic who would make all possessions collective."21 It is, however, interesting to note what the conservative Southern Review from Charleston said in reference to Skidmore's use of Thomas Jefferson's passage on the right to "life, liberty, and property." Rather than accusing Skidmore of corrupting the quotation, they wrote that while they held Jefferson in the highest esteem as the greatest leader, they "hold that part of the Declaration of Independence to be mere words without meaning; or untrue in respect of any meaning that can reasonably be attached to them. Let him defend them who can."22 Debates about Republicanism certainly appealed to readers by playing with the familiar imagery of a figure like Paine or Jefferson, but they should not be seen as the guiding principles of a political party founded for material, rather than ideological reasons. At the end of the day, it was Skidmore's statements about the duty and obligations of fathers that captivated Working Men as they sat in their homes.

The central tenet of Skidmore's agrarian ideology was that all current property claims were unnatural and illegitimate; a new state constitution should be drafted in order to abolish all debts and redistribute land to all adult citizens through a "General Division of Property."23 The state would repeat the equal redistribution of land in successive generations and abolish inheritance until inequality and corruption died out. Since the state rather than the individual would have the power to distribute land, new understandings of property rights and the use of property would necessarily develop. For Skidmore, the main function of property was the maintenance of children. He clarified what this meant for fathers and children by writing:

If, however, the government should distribute to each family, in proportion to the number of its members, it would be to disavow the principle that a child is to look to its parent for support, and to declare that its claims rested upon the community. And this places the reliance where it ought to be, upon the rights of the being receiving support, and not upon the benevolence, of parents or others… That these children have it in their own right, and not in the right of their parents, is evident, not only from this, that large families have more than small families, in proportion to their numbers; but also from this, that those children who have lost their parents, nevertheless have as much as those whose parents are living.24

Anticipating "Rights of Children," Skidmore objected to the dependent relationship of children to their fathers because it did not account for the rights of children and left their maintenance to mere patriarchal whim. Skidmore predicated his fear of parental failure on the notion that current economic conditions did not allow the individual working man the opportunity to assure his family's survival. Disparities of societal wealth stripped men of their ability to properly provide for their children's maintenance. For Skidmore, the easiest way to fix the problem of unsupported children was to have the state assume some of the obligation to care for and maintain children, while relieving fathers of the struggle to accumulate property to pass along to the next generation.

A number of immediate problems contributed to Skidmore's concern about the ability of fathers to provide for their children. The harsh winter of 1829 offered a difficult test for workers and their families. Newspaper reports from the winter and early spring recount the large number of individuals seeking firewood, food, and any type of work they could get. According to the New York Evening Post, more than 2,000 people sought poor relief in the Fifth Ward alone over a single weekend. The same issue mentioned the establishment of "a general Soup House for the poor of the city."25 Poor economic conditions did not quickly evaporate, and individual city wards still struggled to provide food and necessities for their residents in the final days of the Working Men's Party.26 The inability to find employment and support one's family obviously weighed heavily on many working men. One paper reported that "thousands of industrious mechanics, who never before had solicited alms, were brought to the humiliating condition of applying for assistance, and with tears on their manly cheeks, confessed their inability to provide food or clothing for their families."27

Skidmore reacted to the increasing difficulty fathers experienced in providing for their children when he created a plan that relieved them of such obligations. Attempting to probe Skidmore's personal psychology for other causal links is a dangerous endeavor, but a few events from his life should be considered to provide more context for his ideas about property and father-son relations. As a working teenager, Skidmore continually fought with his own poor father about being able to retain some of his wages and eventually left home over the issue. The pressure of the struggle over property between poor fathers and their sons was clear when he wrote:

… when men therefore, say they seek to supply the wants, the future wants of their children, they deceive themselves. All the fathers of any generation, under the present order of things, may be considered as engaged in a struggle, not to supply the wants, the future wants, each of his own children, out of the labor of such parents; but to compel the children of some of these fathers, (and it happens to be a great majority of them), to labor for and supply the wants of the others, while these last riot in idleness and luxury.2820

Whether it was out of his own distrust of fathers to properly provide for their children or a realization that it was becoming much harder for many men to do so, Skidmore's ideology reflected a desire to alter traditional ideas of fatherly obligation and responsibility. Soon other Working Men openly challenged his ideas.29

The most damaging attacks on Skidmore came from other Workies with different visions of fatherhood who wanted the WMP's apparatus to promote them. During the mass meeting on December 29, 1829, Noah Cook proposed resolutions that distanced the party from Skidmore and reestablished it in a new direction. The statements made sure to amplify the WMP's objection to Skidmore's notion of property relations, inheritance, and fatherhood. In lieu of communal, State-divided property, Cook affirmed individual property rights by offering workies a more reassuring and stable vision of fatherhood and household-based masculinity. Cook noted that the Working Men had "no desire or intention of disturbing the rights of property in individuals, or the public." Instead, he said, we "consider the acquiring of property to soften the asperities of sickness, of age, and for the benefit of our posterity, as one of the greatest incentives to industry."30

This model of fatherhood successfully tied hard work to a legacy for future generations and one's own peaceful retirement and at the same time recalled a classic idea of household-based masculine responsibility. Cook offered Working Men a more recognizable, if more moderate, version of fatherhood. It struck a chord because, for most working fathers, relinquishing inheritance and property rights deprived them of domestic responsibilities that although difficult to fulfill, were central to their self-identification as husbands and fathers. The promise of relief from the pressure and obligations of parental support probably intrigued many Workies, but at the end of the day, it did not reflect their attitudes toward their roles as fathers. Skidmore never relinquished his agrarianism, but after the December meeting, few listened.31 Long after the mainstream WMP isolated him, Skidmore continued to send letters to the Free Enquirer urging the party to rethink its position on fatherhood and property. The vast majority of WMP members never came around to his way of thinking.32

For Robert Dale Owen's and Noah Cook's factions, the danger of aligning one's political future with agrarianism and its model of household-based masculinity was apparent. George Henry Evans and other Owenites' initial tacit approval of the party's agrarian resolutions eroded within weeks. Within the month of November, Evans' Working Man's Advocate actually changed its banner from "All children are entitled to equal education; all adults to equal property, and all mankind to equal privileges" to "All children are entitled to equal education; all adults, to equal privileges."33 As well as decisively rejecting agrarianism, the new banner also spoke to the ongoing battle between Skidmorites and Owenites over which system best enabled fathers to benefit their children and the next generation. Owen's supporters spelled out their warning simply: "avoid SECTARIAN DIVISION, and seek justice and equality, THROUGH EDUCATION, FOR YOUR CHILDREN, not THROUGH AGRARIAN LAWS, FOR YOURSELVES."34 The argument even outlasted the WMP's political viability.

Amos Gilbert, who succeeded Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright as editor of the Free Enquirer, traded barbs with Thomas Skidmore on the issue for three weeks in December 1831. The exchange between Gilbert and Skidmore did not aid the Working Men's Party in the electoral arena, but it was one of the clearest examples of the difference between the two groups concerning their attitudes toward fatherhood. The debate boiled down to differing ideas on how to best ensure that coming generations would enjoy a world of equality. Skidmore insisted that all adult individuals should be given property in order to ensure the equality of their positions. He asked, "would it be wrong that, male and female, the children of one family should have given to them, by their parents, on arriving at the age of maturity, as much of property with which to commence their career in life, as the children of another?"35 His notion of property relations had progressed from his 1829 work, but still contained the idea that children had natural property rights whether they were from wealthy or poor families.36

25Amos Gilbert's plan, following Robert Dale Owen's ideas on state guardianship, hinged upon the notion that the next generation needed equal education before it could handle the responsibility of equal property. He stopped just short of saying that the future was more critical than the present, writing:

I do consider the proper training of the rising generation at any time, of much greater importance than attention to the physical comfort of adults (I am thinking of our circumstances in the United States) badly as it is attended to—much as improvement is called for in that matter; the former effects one generation who have lived out half their time, and them only; the latter directly, concerns a generation just entered upon the arena of existence; and indirectly, all posterity.37

This bold statement must have been hard to swallow for a number of fathers reading the paper. While it squared with the idea of parental duty, it plainly asked working fathers to sacrifice their own comfort for the benefit of future generations.

The basic disagreement between Skidmore and Gilbert (and by extension Owen) came down to this question: should society fix the adults or the children first? Their final passages summed up each man's answer. Skidmore asked a pertinent rhetorical question: "When did a nation of miserable parents bring forth a nation of happy children? …shew me a nation of happy fathers and mothers, I will shew you a nation of happy children."38 Gilbert responded, "Show me a nation of men trained in wisdom and virtue …and I will show him one, in which not only all children are receiving rational, equal education—but one where all adults have the means of living in abundance."39

Public Education

Just as Thomas Skidmore's faction tied its vision of fatherhood to its agrarian plan, Robert Dale Owen's faction championed its state guardianship system of public education. All three WMP factions agreed on the need for publicly funded education, but varied greatly in their implementation. The issue was so central to the WMP, that some even declared that there would be no need for the party after settling the issue. The December 1829 meeting pledged that "the first subject which should engross our attention, or for which the public funds should be appropriated, is education. When this shall have been effectually attended to, we will cheerfully unite in support of any other just and feasible object."40 General resolutions at the meeting supported this call for publicly funded education, but the party delayed decisions about the party's official school program until a party subcommittee could study the issue in more depth. Not surprisingly, an educational system that satisfied all three factions of the party never materialized. The greatest difference among the Working Men's competing educational plans was the relationship each conceived between the educational apparatus and the family. Robert Dale Owen's state guardianship system was the most sweeping and original. A series of pamphlets by Owen, several public speeches by Frances Wright, numerous articles in the Free Enquirer, Daily Sentinel, and Working Man's Advocate, and the education subcommittee minority report detailed the plan.41

Based somewhat on Owen's recollections of his own education in Hofwyl, Switzerland, the system called for the state to remove children from their homes at age two and send them to a boarding school where they would all receive identical food, clothing, shelter, and education following the Pestalozzian model until they matured at age sixteen.42 Unlike day students, they would remain at the academies without vacations and would be allowed to see their parents only on very special occasions. For Owen, the basis of the plan was that if children received an equal education they would become equal adults, and thus the contemporary problems of poverty, aristocracy, and injustice would be solved. Owen produced dozens of contemporary explanations of the plan, including the following passage:

Had equal education been given in the last generation to the child of the poor as well as the rich—to the child of the mechanic as well as the president, how many parents would have been spared the sharpest and bitterest pangs of poverty—how many would have been spared the pain of anticipating their children's future hardships and degradation … Thus is the miserable condition of the working people to be traced to the carelessness of mankind in neglecting to train up children, when young, in the way they should go—to impress upon their minds the nature and value of their privileges as freemen.4330

This sentiment conveyed Owen's two main philanthropic ideas. First, an increase in education would tangibly affect the quality of life and the ability of working people to succeed. Second, the importance and duties of newly-granted suffrage and citizenship needed to be taught to the rising generation so that they would know how to use them properly.

Owen acknowledged that some aspects of this system seemed harsh, but they were necessary to ensure that society eradicated inequality. In his essays on education and again in the WMP' subcommittee on education minority report, he asked:

… [whether] the children from these State Schools are to go every evening, the one to his wealthy parents' soft carpeted drawing-room, and the other to his poor father's, or widowed mother's comfortless cabin, will they return next day as friends and equals? He knows little of human nature who thinks they will. Again, if it is to be left to the parent's taste, and pecuniary means to clothe their children as they please and as they can, the one in braided broad-cloth and velvet cap, and the other in thread-bare homespun, will they meet as friends and equals?44

Related document:

Sheet Music to Owen's Song

The state guardianship system offered little immediate reward for working fathers or other voters, but if realized, it

promised a more equal society for the next and future generations of children. This was quite a sacrifice to ask from

WMP fathers. For Owen and his supporters, however, this sacrifice was the very litmus test of Working Men's commitment

to their household-based masculinity. "Real" Working Men would be proud to give up their children (and taxes) to send

them to an academy that created a just and equal society. Ironically, because Owen was one of the few unmarried and

childless Working Men, he could not lead by example. Owen later married and even penned a song called 'Tis Home

Where'er the Heart Is, but such measures came too little, too late for his early critics.45

Owen's tough-love model of masculine fatherhood did not gain uniform acceptance among Working Men and the system's detractors offered alternative plans. On the surface, Thomas Skidmore's educational plan in The Rights of Man to Property! did not vary greatly from the state guardianship system. He too called for the state to pay for children's education, clothing, and maintenance, but he made these benefits contingent upon parents' ability "to train up their children."46 This seemingly small difference became a major point of contention because the question of fatherly duty lay at its heart.

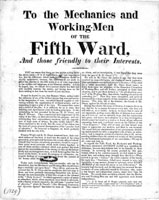

Broadside to Working Men of the Fifth Ward, 1830

Given that household-based fatherhood issues grounded the Working Men's platform, even small conflicts erupted into larger

discussions over masculinity. If a father's prerogative was to oversee the training of the next generation, the state

guardianship system deprived him of that role. Likewise, if a father's duty was to ensure the best opportunity for his

children, then perhaps recognizing the state guardianship system better fulfilled this obligation. For Skidmore,

the bond between father and child meant that one should not suffer for the benefit of the other. He asked Owen whether, "an

attention to the education of his children (even to the extent he has named) was the most important object that could be

presented to him, at the same time that, with the madness of suicide, he forbore to look after the happiness, by demanding the

rights of their father?"47 Whereas Owen's system necessitated sacrifice by

fathers, Skidmore was not prepared to subject fathers to such consequences in the cause of education.

Broadside to Working Men of the Fifth Ward, 1830

Given that household-based fatherhood issues grounded the Working Men's platform, even small conflicts erupted into larger

discussions over masculinity. If a father's prerogative was to oversee the training of the next generation, the state

guardianship system deprived him of that role. Likewise, if a father's duty was to ensure the best opportunity for his

children, then perhaps recognizing the state guardianship system better fulfilled this obligation. For Skidmore,

the bond between father and child meant that one should not suffer for the benefit of the other. He asked Owen whether, "an

attention to the education of his children (even to the extent he has named) was the most important object that could be

presented to him, at the same time that, with the madness of suicide, he forbore to look after the happiness, by demanding the

rights of their father?"47 Whereas Owen's system necessitated sacrifice by

fathers, Skidmore was not prepared to subject fathers to such consequences in the cause of education.

Noah Cook's faction of more moderate reformers, including Aaron L. Balch, a teacher from the Fifth Ward, posed a more serious challenge to Owen's state guardianship system of education. The Cook and Owen factions aligned temporarily in late 1829 and early 1830 in order to oust Thomas Skidmore from party leadership, but the groups split decisively on the issue of education. Embracing a more traditional patriarchal model of fatherhood, Cook, Balch, and others favored a school system where parents maintained an active oversight authority. They supported the ideal of Owen's plan for boarding schools where children would be "instructed, fed and clothed alike, and that this should be all done at the public expense," but their approval of the system contained one large caveat: parental choice.48 Noah Cook emphatically declared:

It should be entirely VOLUNTARY on the parts of the PARENTS whether they send their children to these [boarding] schools or not. We maintain that it shall be optional with parents where and when to send their children to school, because they, and they alone, are the natural and rightful guardians of their offspring, and NO POWER ON EARTH HAS ANY RIGHT TO CONTROL THEM.49

The proclamation's strong language asserted that a father's rights were superior to the state in regard to his children's education. Cook's faction looked positively on the potential benefits of boarding school education, even at public expense, but the important decision of whether or not to remove the child from the home rested with the father. If the state could come into the domestic arena to overstep a father's dominion, they asked, would not their families be subject to the whim of "the State guardianship of the Daily Sentinel, which 'abandons' the children of the Republic 'to the world?'"50 While Robert Dale Owen's plan accepted that paternal control of children needed to be augmented to ensure the societal benefits of equal education, Cook's followers refused to allow such liberties. They hoped "for a republican system of education," but only supported a "plan that shall leave to the father and the affectionate mother the enjoyment of the society of their offspring."51 In place of Owen's ambitious state guardianship system, Cook's camp proposed a more moderate educational system.

Cook's followers called for publicly funded education, but their approach concentrated on less expensive and ambitious ideas in order to allow fathers more flexibility. A lengthy editorial by Cook on how to get the "attention of Parents" to best establish a useful school program focused on teacher qualifications and the importance of rural education. He argued that like any other artisan or tradesman, teachers selected to care for families' needs should be well-trained and qualified. Teacher selection particularly mattered because "three-fourths of the parents in this State, who have children at school, do not visit and examine those schools once in a year." Reflecting this concern, Cook's utilitarian educational plan proposed that, "a board of County or State Censors perhaps, who should examine and grant certificates to all teachers, would be desirable. Each district should be culpable to a certain amount for employing any other teachers, and a further penalty should be imposed upon each district which did not sustain a school."52

While this particular plan lacked the overall thrust and scope of Owen's or Skidmore's approach, it seemed attainable, cost-effective, and aligned with many Working Men's model of fatherhood. Most Workies supported the idea of creating an equal society through education, but they had no desire to give up their children to the prerogative of the state to achieve educational reform. Within this reality, an improved school system that promised fathers a moderate level of publicly funded instruction for their children certainly seemed encouraging.53

The lack of educational opportunities for Working Men's children, both real and perceived, highlighted the importance of all three plans for better public school services. It is difficult to determine exactly how many children received some education in these years, but a few statistics merit close inspection. One newspaper report noted that it was "stated in the able report of the Committee to whom were referred the memorials of the trustees and other citizens, that there are 20,000 children in this city between the ages of 5 and 15, who attend no school whatever."54 Of those who attended, many frequented only religious or charity schools. Such figures alarmed Working Men. Knowing that whatever instruction children received bolstered their chances of economic success, artisan fathers who could not afford school fees personally lamented the state of education. With the apprentice system breaking down and the de-skilling of artisanal work, fathers viewed education as a way to buttress or augment craft knowledge while engaging the work arena.55

40Philanthropist Robert Dale Owen observed public school attendance figures with a very different eye. Firstly, these figures demonstrated the pressing need for publicly funded, universal education as a means of social uplift to prevent pauperism and ignorance. Secondly, they confirmed the role that religious organizations played in the education of the next generation. For a free thinking, anti-religious man like Owen, the desire to place the state in control of the educational system was at least partly driven by an attempt to deny the clergy access to children's minds.56 Unfortunately for him (and fortunately for Cook, who quickly exploited the plan), this irreligious view contradicted many working fathers' opinions. The conflict over education revealed that the issue of religion and worker morality lurked in the background of the divide between the Owenite and Cookite factions.

Worker Morality and Religion

Even though Owen's writings played down his personal irreligiousity, for years to come detractors painted him as a dangerous free-thinking radical of questionable morality.57 Owen served as a secretary at the October 19, 1829 WMP meeting that endorsed Skidmore's agrarian plan, and even though he later said that he was there in an informal capacity, the "agrarian" label stuck.58 Furthermore, Owen's association with his father's failed utopian community at New Harmony and Fanny Wright's planned community at Nashoba opened Owenites up to the charge of being anti-social communitarians.59

Dr. Cornelius Blatchly, one of Owen's allies and an unsuccessful candidate in 1829, also supported planned communities. He had been a member of the New York Society for Promoting Communities in the early 1820s (an organization associated with Robert Owen) and had even written a couple of his own radical tracts.60 Observing all of these coincidences, one religious newspaper differentiated between Cook's moral faction and Owen's free-thinking faction, writing that the "true workingmen have, in an open and manly manner, disavowed all connection with agrarian infidelity …We hesitate not to express our opposition to a 'community of property,' and especially on the principles or by the means proposed and advocated by Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright."61 In the battle between WMP factions over the label of "true workingmen," those who objected to agrarianism boasted of their manly behavior because they rejected those parts of the platform that, in their opinion, upheld a questionable morality.

Like other foci of discord within the Working Men's Party, discussions of worker morality exposed factional differences concerning fatherhood. While a number of historical studies detail the battle between Robert Dale Owen's camp and Noah Cook's followers, they primarily join Edward Pessen in accepting Owen's view that Cook's forces who usurped the party leadership included mostly political opportunists who "had little in common with true workmen" and merely hoped to cash in on the Working Men's success in the 1829 campaign.62 Pessen's argument is echoed by Sean Wilentz, who writes that "Cook and Guyon would prove (in a most ungentlemanly way), anti-Jacksonian entrepreneurial causes could be advanced with the help of some very unlikely allies, amid some uncommon political circumstances."63 Wilentz also tries to analyze the election results in 1830 to demonstrate that Cook's support came from aristocratic wards, but this argument is debatable. Based on per capita wealth in 1830, the poorest ward was the Thirteenth, in which Cook's faction earned 42.7% of the vote, significantly more than their overall city average of 34.9%, while Owen's faction received only 5.3% as compared to 10.7% citywide.64 Probing the issue of worker morality and utilizing some previously uncited sources created by Cook's faction allows for an alternate reading of the situation where the household, rather than only the ballot box, becomes the site of some of the differences between the factions. This section argues that Cook's followers believed their own rhetoric about domestic morality and temperance and in turn gained control of the party by earning support from a number of religious sources critical of Owen's supposed lack of faith and family values.

Two main factors enabled Cook's men to take control of the WMP in New York City: support from religious temperance reformers and support from upstate Workies, most notably Albany's Working Men's Party. Cook easily found powerful allies to aid his assault on Owen by questioning the latter's moral fiber. Working Men did not take the endeavor of employing religious assaults lightly. One out-of-town paper even warned the WMP not to walk the path of religious wrangling, reminding them that "in pecuniary matters we may unite, but in religion we never can. Religion is a subject of practice, rather than newspaper disputation."65 Because it was risky to bring religion (or irreligion) into politics, religious attacks scrupulously avoided focusing on theology or biblical interpretations; instead, they tied the issue of worker morality to gender relations, family dynamics, and fatherhood.

45Although Owen portrayed Cook as a lip-service Christian, the prospectus of his own newspaper, the New-York Reformer, Farmers', Mechanics', and Working Men's Champion explicitly displayed Cook's religious concerns. Alongside clearly identifiable WMP issues such as "a Republican System of Education," "Abolition of Imprisonment for Debt," and Cook's dislike of "all legal, official, and other aristocratic monopolies," the heading declared Cook's opposition to "public profligacy and immorality."66 This did not win the support of any free-thinking Owenites, but it did match up with the prospectus of the local temperance newspaper edited by evangelical William Goodell. Goodell's newspaper, the Genius of Temperance, Philanthropist and People's Advocate, declared itself unaffiliated with any of the factions, but gave tacit support to Cook's platform. The paper advocated temperance and railed against the immorality of the public theatre while it supported "General education at public expense, in consistency with parental duties and rights; the abolition of the imprisonment of honest debtors," and opposed "a system of monopolies" and "the oppressions of an effeminate and knavish aristocracy."67

The two papers complemented each other well: Cook's offered Christian morality for Working Men, and Goodell's offered Workie content for Christian moralizers. An example from Goodell's paper comes from the article, "Two Sorts of Workies," which recounted the story of a man returning upstate from a visit to New York City. He reported to his friends that he had attended some meetings at the "North American Hotel" (where Cook's faction met) and read many WMP newspapers. He concluded that two groups of Working Men existed, "the cold water workies, and the Fanny Wright workies; though he thought there were more dandies and rakes, than working men in the latter class."68 This story served two main purposes: first, to designate Cook's faction as temperance advocates, thereby claiming their correct position as carrier of the Working Men's moral banner, and second, to label Owen's followers as individuals with questionable moral and household-based masculinity credentials. Owen's critics often used the label "Fanny Wright Men" to finger the faction as weak and under the political control of a woman. Given the supposed lack of political capital women wielded in 1830, such a comment effectively questioned the strength and independence of Owen's faction. Adding to this remark the terms "dandy and rake" also sought to expose Owen's free-thinking followers as pretenders, rather than protectors of domesticity and fatherhood. The anecdote also conveyed a more subtle message of the link between Cook's faction and upstate religious support. Owen himself recognized the pairing, referring to Cook's 1830 election ticket as the "Church and State Party."69

By the election of 1830, Thomas Skidmore's faction was not numerically strong enough to fully influence these debates, but it can be quickly noted that some of its members offered other interesting perspectives on moral and religious issues. George Houston, one of Skidmore's closest associates earlier served two and a half years in Newgate prison for publishing the first English translation of Baron d'Holbach's irreligious text L'Histoire de JÚsus Christ (republished by Houston as Ecce Homo; Or a Critical Inquiry into the History of Jesus of Nazareth) which examined the life of Jesus as a human man and not the son of God.70 In the months leading up to the formation of the WMP, Houston's free enquiry newspaper The Correspondent, printed both temperance and anti-religious articles. One editorial noted both that "Drunkenness expels reason …causes internal, external, and incurable wounds; is a witch to the senses, a devil to the soul, a thief to the purse, the beggar's companion, a wife's woe, and children's sorrow" and that "Religion expels reason, destroys the memory, drowns the understanding …is a thief to the purse, the dupe's companion …the parent of priestcraft, a foe to learning, and the friend of tyrants."71 Falling somewhere between Cook's and Owen's views, Houston presented a secular, humanist morality, but like other Working Men, a morality concerned with household and parental relations. In the late 1820s, Houston's daughter even aided her father's activities by running the Minerva Institution, a free-thought school in New York City.72

Ultimately, however, Noah Cook's faction gained dominance in the party because it formed solid alliances with upstate Working Men who responded positively to the Cookites' persona as defenders of a moderate patriarchal vision of moral and temperate fatherhood. Working Men's Parties outside the city in places like Troy, Utica, and Albany included a large percentage of men who did not subscribe to Skidmore's or Owen's radical agenda, but supported Cook's discussion of worker morality.73 Whether or not Cook's religiosity was a sham, as Owen's forces claimed, it convinced those outside the city.74 A Greenfield paper in support of Cook wrote that critics stigmatized the WMP "by asserting that they are infidels—that their object is the overthrow of religion! This base report will prove as futile as it is ridiculous. It has been promptly met and put down by the working men themselves."75

Upstate support came most substantially from the Albany Working Men's Party which formed when mechanic and Methodist civic groups combined their interests to unseat longstanding Dutch-Calvinist merchants (the so-called "Albany Regency") from political power.76 Just as Cook's worker morality faction aligned with Goodell's temperance message in the city, it subsequently partnered with the Albany WMP and their frequent appeals about the dangers of drinking in the country. These groups targeted fathers and husbands in particular in order to remind them about their duties to their children. One Albany Working Men's newspaper article cited the story of a sweet, loving couple that ended up poor, sick, and violent; apparently the difficulties "had grown out of the husband's intemperate drinking and smoking."77

50

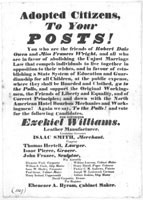

Working Men's Poster to Immigrant Voters, 1830

The Cook faction not only used the issue of religious morality to preach to the converted, but also aimed its attacks

squarely at Robert Dale Owen and his irreligion. Such attacks focused on the way Owen's camp endangered gender norms and

offered a corrupting vision to the rising generation. Critics challenged Owen's ability to act as a spokesman for working

fathers because he himself lacked the political capital of having his own wife and children. Another problem for Cook was

that the Owenites seemed openly hostile to the institution of marriage. One campaign poster from 1830 addressed to "adopted

citizens" who were friendly to "Robert Dale Owen and Miss Frances Wright" and hostile to the "North American

Hotel Bourbon Mechanics" (Cookites) appealed for votes based on the faction's desire to reform divorce laws. Alongside support

for other standard issues such as "State System of Education and Guardianship for all Children," the handbill championed the

idea of "abolishing the Unjust Marriage Law that compels individuals to live together in opposition to their

wishes."78

Working Men's Poster to Immigrant Voters, 1830

The Cook faction not only used the issue of religious morality to preach to the converted, but also aimed its attacks

squarely at Robert Dale Owen and his irreligion. Such attacks focused on the way Owen's camp endangered gender norms and

offered a corrupting vision to the rising generation. Critics challenged Owen's ability to act as a spokesman for working

fathers because he himself lacked the political capital of having his own wife and children. Another problem for Cook was

that the Owenites seemed openly hostile to the institution of marriage. One campaign poster from 1830 addressed to "adopted

citizens" who were friendly to "Robert Dale Owen and Miss Frances Wright" and hostile to the "North American

Hotel Bourbon Mechanics" (Cookites) appealed for votes based on the faction's desire to reform divorce laws. Alongside support

for other standard issues such as "State System of Education and Guardianship for all Children," the handbill championed the

idea of "abolishing the Unjust Marriage Law that compels individuals to live together in opposition to their

wishes."78

Likewise, Cook expressed the fear that Owen's personal belief system adversely effected the party's position on fatherly duty, women's roles, and children's education. One newspaper correspondent insisted that Owen's writings had, "for their tendency improper objects, and insidiously inculcating doctrines which no Christian, no father, no brother, with one spark of feeling or love in his disposition, could for a moment tolerate."79 While not overly prudish, Cook's Working Men tried to distance themselves from ideologies they deemed morally questionable. William Goodell brought these concerns together while attacking Owen's state guardianship system. He wrote:

… as parental authority and instruction were thus to be laid aside, and as the 'national' schools were to furnish no religious instruction, the public were promised a rising generation, freed from the shackles of religious principle. The way was thus to be prepared for that equal division of property, and unrestrained intercourse of the sexes which had been attempted by Fanny Wright, in her settlement at Nashoba.80

This statement condemned Owen's educational plan because it conflicted with parental wishes to give children a religious education. Without religious grounding, the paper warned, children would be defenseless against immoral behavior and the corrupting will of "infidels" like Fanny Wright and Robert Dale Owen.

Frances Wright's connection to Robert Dale Owen rendered his faction vulnerable to a wide variety of attacks over their perceived support of immoral behavior such as inverting gender norms and radically changing family dynamics.81 In a review of the pamphlet, "Fanny Wright, Unmasked by Her Own Pen," the Genius of Temperance exposed what they saw as the true danger of Wright's ideology. Echoing its opinion of Owen's educational system, the review feared how Wright's teachings assaulted marriage roles because:

… the promiscuous intercourse of the sexes, she thinks, would 'promote happiness.' Therefore she spurns the restraints of matrimony. Every other human being may lawfully claim the same 'equal rights' that may be lawfully claimed by Fanny Wright…. The debauchee finds his pleasure and happiness in the promised paradise of Fanny Wright.82

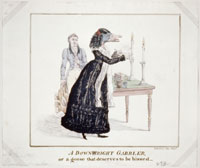

Frances Wright Portrayed as a Babbling Goose

The last statement clearly linked Wright's immorality and her challenge to the institution of marriage with particular aspects

of her sexual behavior. Frances Wright's persona, as well as actual behavior, received its strongest condemnation, however,

concerning the relationship between morality and the rising generation. Her place as a strong, free-thinking woman in the

middle of a male political movement so steeped in fatherhood made her an easy target as the embodiment of moral corruption.

One article told the story of a respectable man forced to "confine one of his four sons, in the House of Refuge, he having

essayed to throw off all restraint, moral, religious and parental, comfortably with the doctrine taught by Fanny

Wright."83 Apparently the boy heard some of Wright's public lectures and lost

his way. 84

Frances Wright Portrayed as a Babbling Goose

The last statement clearly linked Wright's immorality and her challenge to the institution of marriage with particular aspects

of her sexual behavior. Frances Wright's persona, as well as actual behavior, received its strongest condemnation, however,

concerning the relationship between morality and the rising generation. Her place as a strong, free-thinking woman in the

middle of a male political movement so steeped in fatherhood made her an easy target as the embodiment of moral corruption.

One article told the story of a respectable man forced to "confine one of his four sons, in the House of Refuge, he having

essayed to throw off all restraint, moral, religious and parental, comfortably with the doctrine taught by Fanny

Wright."83 Apparently the boy heard some of Wright's public lectures and lost

his way. 84

Similar anecdotes appeared throughout the period to warn fathers of the dangers of the irreligious Owenite faction. Because domestic maintenance was so intimately implied in political rhetoric, such discussions were not merely helpful lessons on Christian morality; they were political pitches for the soul of the Working Men's Party. Although moral Working Men attacked Robert Dale Owen and Fanny Wright for their assault on traditional marriage and corruption of youth, it was not until Owen began publishing his notions of population control that his detractors unleashed their most virulent and personal denunciations.

Birth Control

The conflict surrounding birth control and the Working Men's Party began when Robert Dale Owen sent some innocuous lithographs from England to the Typographical Society of New York, an organization of small master printers, but it soon grew into a major point of political contention over the rights of fathers to govern their families. During the discussion of what was to be done with the prints, Adoniram Chandler, an evangelical temperance advocate and leader of the Cook faction, stood up and read some controversial excerpts from Richard Carlile's Every Woman's Book, or, What is Love? He then asked the society whether they should accept any gift from someone who sanctioned this scandalous work. Carlile's book, originally published in London in 1826, offered a number of suggestions on methods of birth control and had received a mostly positive review from Robert Dale Owen two years earlier.85

Related document:

Typographical Society Response to Robert Dale Owen

Owen may not have totally supported Carlile's book, but his connection to the radical, irreligious author was well established.

At a Fourth of July celebration in 1829 for Free Enquirers sponsored by Owen, the keynote speaker toasted "Richard Carlile—May

his manly and virtuous independence in the cause of antisuperstition, meet with the cordial sympathy and imitation of the professed

antisuperstitionists of the new world."86 From Adoniram Chandler's point of view,

discussion of birth control suggested a potential threat to fatherhood and the possibility of an immoral, destabilizing vision of

household-based masculinity. The Typographical Society referred to itself as "men who, as husbands, fathers, brothers and sons,

reverence the pure principle of chastity in either sex, not only as a cardinal virtue, but as the chief, the head and

fountain of all other virtues."87 Such statements supported their vision of

virtuous fatherhood and expressed outrage because Owen supported Carlile's book. The attacks became more explicit as Owen

formulated and wrote down his own ideas on birth control.

The argument with the Typographical Society did not occur by happenstance. Adoniram Chandler most likely used the meeting to ambush Owen, whom he intensely disliked and labeled as less than a real man, "hanging to the skirts of a deluded woman."88 By linking Owen to Carlile, Chandler quickly enlisted the moral rage of the conservative Typographical Society and started a feud that continued in the pages of the Free Enquirer and other publications for months, forcing Owen to rethink and elaborate on his own ideas.89 During the course of the debate, Owen produced Moral Physiology; or, a Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question, the first birth control tract in American history. As a result he felt the wrath of both religious moralizing Cookites and Thomas Skidmore's personal version of Genesis 35:11 ("Be fruitful and multiply.")90 While the blow-by-blow machinations of this argument are fascinating, this discussion demonstrates how the opposing viewpoints reflected competing versions of fatherhood.

That Robert Dale Owen even discussed limiting family size insulted Thomas Skidmore, who entered the debate attacking Owen's proposals. Well before the publication of Moral Physiology, Skidmore ran articles on the subject in his own paper, The Friend of Equal Rights and sent letters to the Free Enquirer forcing Owen to write an expanded view of his ideas. Owen's biographer, Richard William Leopold, astutely wrote that it was, "Thomas Skidmore, class-conscious leader of the New York workingmen, who paved the way for the first American birth control tract."91 But before moving to Skidmore's several-fronted assault on Owen's ideas about birth control, it is important to delineate exactly what Robert Dale Owen said on the issue and the ramifications of his position for fatherhood and household-based masculinity.

60In many ways, Moral Physiology brought together a number of different aspects of Owen's philanthropic philosophy and his vision of ideal fatherhood. At least part of the tract laid down his ideas on free love and his support for more liberal views of sexuality.92 He intended the work to be both a scientific (physiological) work and a moral treatise; as such, he assured the reader that he was writing neither for the pleasure of "Libertines and debauchees!" nor for the consternation of "prudes and hypocrites!"93 Simply stated, Owen disapproved of the way that parents produced children they could not afford to support without first thinking about the consequences. He wrote that, "children that are brought into the world owe their existence, not to deliberate conviction in their parents that their birth was really desirable, but simply to an unreasoning instinct, which men, in the mass, have not learnt either to resist or control."94 This presented more than just an immediate problem for the parents; it caused long lasting problems for society. Owen went on to ask:

Is it not notorious, that the families of the married often increase beyond what a regard for the young beings coming into the world, or the happiness of those who give them birth, would dictate? In how many instances does the hard-working father, and more especially the mother, of a poor family, remain slaves throughout the lives, tugging at the oar of incessant labour, toiling to live, and living only to die; when, if their offspring had been limited to two or three only, they might have enjoyed comfort and comparative affluence!95

This argument was consistent with his attitudes toward education, which favored a Pestalozzian model that tried to manage one's inherent animal instincts. Owen wrote that more than state guardianship of children was necessary to alleviate the plight of working families, because "even such an act of justice [his educational plan] would be no relief from the evils of over-population." Noting that some men "ought never to become parents," Owen accosted "fathers and mothers in humble life! To you my argument comes home, with the force of reality."96 Once he had the attention of working families, he declared that their reproductive processes needed to be more intellectual and that they ought to take into consideration their poor economic situation before procreating.

In spite of these admonitions, Owen's work endeavored to maintain a positive tone. He wrote that his propositions did not attempt to punish poor families but, rather, to help them. He stated that for "married persons, the power of limiting their offspring to their circumstances is most desirable. It may often promote the harmony, peace, and comfort of families; sometimes it may save from bankruptcy and ruin."97 From start to finish the book emphasized the importance of deliberation before procreation, especially for poor parents. Into this discussion, Owen inserted a short closing to the essay that suggested withdrawal as an advisable method of birth control.98

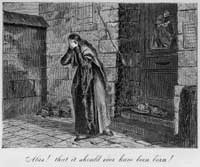

The frontispiece which Owen selected to represent the message of Moral Physiology showed a woman abandoning her baby in

the front of a foundlings' hospital with the caption "Alas, that it should ever have been born!"

Frontispiece to Robert Dale Owen's Moral Physiology

Owen wrote that it was "exceedingly appropriate to the subject, and contains, to my feelings, one of the strongest of arguments

in itself." The price difference between a pamphlet with the frontispieces and one without it reflected importance of the image:

thirty-seven cents and twenty-five cents respectively. Owen did not merely protest that the mother gave up the baby (adding to

the number of poverty-stricken orphans in need of philanthropic aid); he criticized that it had even been born to someone who

could not afford to take care of it.99

Frontispiece to Robert Dale Owen's Moral Physiology

Owen wrote that it was "exceedingly appropriate to the subject, and contains, to my feelings, one of the strongest of arguments

in itself." The price difference between a pamphlet with the frontispieces and one without it reflected importance of the image:

thirty-seven cents and twenty-five cents respectively. Owen did not merely protest that the mother gave up the baby (adding to

the number of poverty-stricken orphans in need of philanthropic aid); he criticized that it had even been born to someone who

could not afford to take care of it.99

While the book had plenty of detractors, it is useful to note one positive reaction and the way the reaction referenced the ideology of fatherhood. An anonymous journeyman wrote to the Free Enquirer stating that "I have been married nearly three years and am the father of two children." Upon reading Moral Physiology, "my visions of poverty and distress vanished; the present seemed gilded with new charms, and the future appeared no longer dreaded."100 Unquestionably, this response was the one Owen wanted: a working father contemplating Owen's argument and readjusting the management of his domestic life as a consequence. However, for every father who enjoyed reading the book, other fathers objected to what they perceived as an attack on their parental rights and reproductive choices. Thomas Skidmore joined the fray and led this second group.

65Skidmore and Owen disagreed on ideal fatherhood as it related to land distribution, inheritance, and education, but the issue of birth control exposed their strongest ideological discord. While Owen worked on Moral Physiology, Thomas Skidmore (or his associate George Houston) anonymously published a pamphlet entitled Robert Dale Owen Unmasked By His Own Pen.101 Written from the point of view of "a husband, and a father, and a MAN," the work targeted Owen as a Carlile supporter, who tried to discredit marriage as an institution and desired to turn all women into prostitutes.102 The pamphlet also attacked Owen's own father and his utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana. The author had likely read Paul Brown's Twelve Months in New Harmony, a scathing assault on the senior Owen and the failure of the community to live up to its own standards.103

Unlike Adoniram Chandler's assault, the anonymous pamphlet declared its lack of interest in Owen's and Fanny Wright's religious lives; rather, it was a blistering personal attack on Owen's own masculinity and model of fatherhood. It explicitly stated, "let R. D. Owen, with the manliness he avows, justify, if he can, those doctrines and practices the 'Every Woman's Book' contains."104 It chastised Carlile, Wright, and Owen for promoting birth control, attacking the "marriage contract," and sanctioning "promiscuous sexual intercourse."105 Without the sanctity of marital vows, questions would arise about a husband's and father's dominion and, the author feared, would lead to the widespread prostitution of working men's wives and daughters. This may seem like an overreaction, but it points out the concern that some men had with Owen's vision of fatherhood and marriage and how they were affected personally by it.

When Thomas Skidmore responded to the fourth edition of Moral Physiology a year later, he replaced the personal attack featured in Robert Dale Owen Unmasked By His Own Pen with a more thoughtful and reasoned commentary. Reprinting Owen's entire uncopyrighted essay, Skidmore added his own footnotes and conclusion for the deftly-titled Moral Physiology Exposed and Refuted, By Thomas Skidmore. Comprising the Entire Work of Robert Dale Owen On that Subject, With Critical Notes Showing Its Tendency to Degrade and Render Still More Unhappy Than it is Now, the Condition of the Working Classes, By Denying Their Right to Increase the Number of Their Children; and Recommending the Same Odious Means to Suppress Such Increase as are Contained in Carlile's: 'What is Love, or, Every Woman's Book.'106 As the title suggested, Skidmore believed that birth control would both limit working families' natural reproductive rights and further depress their lives. He questioned Owen's premise that the world was too crowded, especially in terms of Working Men and their families, writing that "the world is not now overpeopled, nor is it likely to be in hundreds of generations."107

Turning Owen's argument on its head, Skidmore argued that the socioeconomic condition of Working Men, as loving fathers and husbands, actually improved with more children. The working population, he stated, "ought to be increased; because society will be the happier."108 This argument set up a dichotomy between two very different visions of domestic economy and its relationship to fatherhood. Owen assumed that the fewer children a poor father provided for, the more he could do for each individually and the happier everyone in the family would be. Skidmore posited that the more children a father had, the happier he would be, regardless of wealth, because of the domestic bond and the additional love extra family members brought. Besides, Skidmore noted, preventing reproduction limited the rights of children who would not be born. Even though these competing figures offered Working Men disparate images of fatherhood to rally around, they both tied important issues of the day to domestic economy, because Working Men entered the political arena through their household-based masculinity and on behalf of their families.

While this discussion of birth control and the place of children in society seems to drift far from the political intrigue and raucous factionalism that usually characterizes narratives of the Working Men's Party, it is very close to where this chapter began; by stating how the issue of what was best for children was an integral aspect—not just a minor aside—in the short life of the WMP. Within days of Thomas Skidmore publishing his "Rights of Children" article which the chapter began with, the Daily Sentinel and the Free Enquirer responded with "Parental Responsibility." While covering much of the same territory, the article focused on what a parent owed to his children, rather than Skidmore's idea about what natural rights a child possessed. The writer (most likely Robert Dale Owen, who edited both papers at the time) noted that, "every upright parent virtually puts this question to himself, 'How can I best promote my children's happiness?—not my own comfort, not my own self impulses—but my children's virtue and happiness.'"109 Simply stated, a man's life was not his own: it belonged to his children and he needed to make decisions that best educated and guided them. It is critical to note that both Skidmore's "Rights of Children" and Owen's "Parental Responsibility" appeared between late May and early June 1830, just as the party split apart. These weeks marked the high point in the factional division over the state guardianship plan and morality issues as well as the beginning of Robert Dale Owen's frequent discussions of population and moral physiology in the Free Enquirer.

70Arriving in the midst of such events, and given the short life of the Working Men's Party, articles such as "Parental Responsibility" did not appear as an introspective discourse on how to properly treat one's children; they were a call to political action, a political action specifically targeting the issue of fatherhood. The commentary stated that "they who never thought of politics before are the warmest politicians now. The measure agitated is practical, national. It comes home to the feeling of every disinterested parent, and of every honest citizen who knows what human nature might be, and who sees what it is."110 For both the producers of this message and their audience of Workies, the editorial, like all of the discussions detailed in this chapter, referred to a political movement and ideology grounded in the domestic arena. This fact did not make the WMP theoretical lightweights: from agrarianism to state guardianship and birth control, they operated on the cutting edge of contemporary notions of the state and individual rights. Both Working Men and their detractors from around the state of New York and the rest of the country looked to the WMP of New York City and men like Thomas Skidmore and Robert Dale Owen for cues on how to approach radical issues; however, this does not mean that a cohesive party platform ever coalesced. Three individual factions arose, each one rooting its platform and ideology in different notions of proper fatherhood and each one agreeing that "powerful—very powerful is the parental feeling."111

As Chapters Three and Four demonstrated, working men inhabited a world where they repeatedly confronted perceived threats to their ability to provide for their families welfare and uphold their household-based vision of masculine identity. In order to collectively address the concern that their children would be doomed to economic and social inequality if they did not act, organized men formed the Working Men's Party New York between 1829 and 1831 to champion political solutions grounded in their ideas of fatherhood. During the era of the WMP, this meant that a whole set of issues (agrarianism, education, domestic morality, and birth control) came up for debate among a demographically-similar group of men who claimed that they represented the best vision of fatherhood.

Notes:

Note 1: The Friend of Equal Rights as quoted in Mechanics Free Press, July 24, 1830. Thomas Skidmore and Alexander Ming Sr. edited this daily paper that began its run on April 24, 1830; no copies are extant. back

Note 2: When I compared a compiled list of over 600 Working Men with data from the 1830 federal census, the results yielded an average household size of 5.39 individuals of whom nearly 3 were under the age of 20. For more on the demographic profile of New York's organized laborers, see Chapter One. back

Note 3: Contemporaries often used the term "Workies" as a nickname for those who most embodied the values of the WMP. Men from almost every occupational category in the city considered themselves Workies: the label did not reflect or imply a particular type of employment or skill. back

Note 4: The most useful accounts of the WMP are Hobart Berrian, A Brief Sketch of the Origin and Rise of the Working Men's Party in the City of New York (Washington DC: William Greer, 1840); George Henry Evans, History of the Origins and Progress of the Working Men's Party in New York (New York: George Henry Evans, 1842); Frank Carlton, "The Workingmen's Party of New York City, 1829-1831," Political Science Quarterly 22, issue 3 (Sept., 1907), 401-415; John R. Commons and Associates, History of Labour in the United States vol. one, (New York: Macmillian, 1918), 171-172, 231-284; Arthur Schlesinger Jr., The Age of Jackson (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1945), 133-143, 177-216; Seymour Savetsky, "The New York Working Men's Party" (M.A. thesis, Columbia University, 1948); Walter Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class: A Study of the New York Workingmen's Movement, 1829-1837 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1960); Edward Pessen, "The Working Men's Party Revisited," Labor History 3 (Fall, 1963), 203-226; Edward Pessen, Most Uncommon Jacksonians: The Radical Leaders of the Early Labor Movement (Albany: SUNY Press, 1967), 7-33, 58-79, 103-203; and Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 172-216. The following narrative is largely derived from Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class, 12-23 and Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 177-211. back

Note 5: House carpenters and other builders had already worked a ten-hour day for a couple of decades by 1829. See Chapter Five. back

Note 6: The organization began in September of 1829. For more on Owen, see Robert Dale Owen, "An Earnest Sowing of Wild Oats," Atlantic Monthly 34, number 201 (July, 1874), 67-78; Norman E. Himes, "Robert Dale Owen, the Pioneer of American Neo-Malthusianism," American Journal of Sociology 35, issue 4 (Jan., 1930), 529-547; Richard William Leopold, Robert Dale Owen, a Biography (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940), 85-102; Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class, 84-85; Pessen, Most Uncommon Jacksonians, 66-71; and Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 178-215. back

Note 7: For more on Evans, see Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class, 85-88; Pessen, Most Uncommon Jacksonians, 71-75; and Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 192-213. On Blatchly, see David Harris, Socialist Origins in the United States: American Forerunners to Marx 1817-1832 (Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum & Company, 1966), 10-19; and Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 158-167,193-200. back

Note 8: For more on Skidmore, see Harris, Socialist Origins in the United States, 91-139; Amos Gilbert, "A Sketch of the Life of Thomas Skidmore," in Free Enquirer March 30, April 6, 13, 1834; Edward Pessen, "Thomas Skidmore: Agrarian Reformer in the Early American Labor Movement," New York History 25 (July, 1954), 280-294; Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class, 82-84; Pessen, Most Uncommon Jacksonians, 58-66; and Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 182-216. back

Note 9: Owen became managing editor of the Daily Sentinel in February of 1830. On Wright, see Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 176-183, 192-193, 200-212; Celia Morris Eckhardt, Fanny Wright: Rebel in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984); and Lori D. Ginzberg, "'The Hearts of Your Readers Will Shudder': Fanny Wright, Infidelity, and American Freethought," American Quarterly 46, issue 2 (June, 1994), 195-226. back