Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Readers' Guide

Introduction The Narrative Official Stories The Participants Afrikaans Memory and Violence Final Thoughts Archive

Abbreviations Glossary

Gutenberg-e.org Columbia University Press

Chapter 5

Afrikaans

"We Are Fed the Crumbs of Ignorance with Afrikaans as a Poisonous Spoon"—Historical Context and Precipitating Factors

"To Hell with Boere Taal:" Student Voices

Related sections:

Chapter 2, "The Narrative"

Chapter 4, "The Participants"

The students themselves understood the disregard for the political will of the African people in South Africa.98 They saw the ideological issues at stake and recognized this policy change as a misuse of the state's power. In

their own words, student participants in the uprising present us with the concrete evidence of the centrality that Afrikaans had to the

protests and of the profound impact that the Black Consciousness movement had in raising the awareness and understanding of the importance

of this issue. It was "the Afrikaans question that made us to stand together, as students, in one Solidarity to voice our grievances," said

Khotso S. Seatlholo, leader of the SSRC, in a press release on October 29, 1976, after Tsietsi Mashinini's departure. And, returning once

more to the words with which this chapter opened, "through the rejection of Afrikaans we are prepared to break the spine of the whole

immoral White Apartheid Empire."99 Following this statement was an outline of the "main causes

of the present unrest," and there Seatlholo cast his language more broadly, but each of the issues enumerated stood in some direct or indirect

relationship to the issue of compulsory Afrikaans instruction:

(1) The White racist Government's discriminatory racial policies. They have caused unbearable suffering to many Blacks socially, economically and politically.

(2) The Whiteman's arrogance in their refusal to listen to Black man's grievances; and their unpreparedness to consult with Blacks in the making of laws that govern the country.

(3) Lack of contact and communication between Black and White at local and National levels because of the Apartheid policy.

(4) The Whiteman's avarice and readiness to amass all the economic wealth in the country and keep Black races in a perpetual state destitute and poverty. We cannot live on charity and patronisation by Whites.

(5) The undermining of the Students' Power and their determination to free themselves from the oppressive system of education and Government.100

Sifiso Ndlovu, a student at the time and an active participant in the protests, wrote many years after the uprising, when his own training as a historian and the years of hindsight allowed him to cast the issue in a considerably more theoretical language:

In 1975, while we were using English as a medium of instruction, we had to be satisfied with poorly-equipped laboratories and the lack of other necessary resources and facilities. But the use of Afrikaans the following year as a medium of instruction soon compounded the issues. What were initially problems that related to the lack of facilities and resources, now became epistemological and ideological issues which included the (ab)use of language and power.101

In May 1976, students gathering for the annual General Students' Council meeting of SASM, in Roodepoort, a town just outside Johannesburg, had also addressed the issue of Afrikaans as the first item of their agenda. Fully recognizing the "national implications" of the strikes and the schools' complicity in the "systematic producing of 'good Industrial boys' for the powers that be," the students present resolved to "totally reject … this dialect" and to "condemn the racially Separated Educational system."102 The students at this meeting recognized both the implications and pernicious intent of Bantu education made explicit in the new Afrikaans policy, and they recognized its suggestive significance for national political organization.

By making its exclusionary educational goals concrete in the form of implementing a provision that had been on the books for many years, the government delivered into the hands of the students the ideal issue around which to focus protest and resistance. Bantu education, in the larger sense, had angered the students for a long time. At first their demands were relatively modest and their concerns turned mostly around student-teacher relations, the inadequacy of teachers and materials, and what they considered unfair demands on their parents. Students at the Hofmeyr High School in Atteridgeville/Saulsville, for example, articulated these demands that they drew up in a memorandum at the request of their teachers and that they thought would be presented to their school principal and "authorities:"

Hofmeyr High School cannot, according to the grouping of the subjects, produce Medical students who qualify. We know that we are badly in need of Black doctors… 3. Teachers do not report for lessons… 4. Some teachers suffer an inferiority complex and some others suffer a superiority complex they do not treat students as human beings, they even go to the extent of being cruel to the students… 5. Married Male teachers fall in love with schoolgirls only to use them and some of the girls are in love with students and that brings about a fight between teachers and students. 6. When the school wants money for books from the students they are merciless to the students that is they send them home or they are severely caned but when the students want their changes they have to struggle for their changes. This is hard upon the parents who need the money for other purposes. 7. The schools choose expensive uniforms from shops, this is hard for the struggling parents. The child have to leave school because the parents cannot afford to buy a uniform.

At Hofmeyr High School it was not until "after the June riots" that the teaching staff and the principal "were made fully aware" that students wanted a student's representative council, and only then did they explain the importance and scope of their vision:

We believe that it is a system which limits the knowledge of the black children. A system which makes a black person to feel inferior. e.g. We believe that an education that white children are having is better than ours. In that way the white children are superior to us. Bantu Education is education which is not internationally accepted or an international education. A secondary to the whites education.103

The failures of individual teachers or the lack of adequate textbooks, among so many other factors, were never adequate as rallying points, never sufficiently powerful, in and of themselves, to focus resistance. Afrikaans, however, had a multidimensional character and immense symbolic power: It embodied everything that was wrong with Bantu education, highlighting the inadequate preparedness of teachers, the inappropriateness of textbooks (to follow through on the example above), and the impotence both of students and of parents, whose voices were not, as a matter of policy, to be taken into account:

[I]t has never been official policy to grant such permission [for exemption from the 50-50 rule] simply because the parents, the school board, the school or the pupils so desire.104

Students themselves wanted to be heard, and they articulated their thoughts on this issue in many different ways and in different forums, in speeches and in interviews, on placards and flyers, during testimony and in press releases:

[F]ollowing the unrest in our townships, students should give evidence. WE ARE PREPARED TO TAKE THE INITIATIVE. [Italic is added for emphasis; capital letters are in the original.]10575

But they also wanted action, and protests began at the Junior Secondary Schools-those most affected by the Afrikaans ruling. Seth Mazibuko, a 16-year-old student and prefect,106 described in his testimony before the Cillié Commission how the protests started at his school, Phefeni Junior Secondary:

Through early May, 1976, a female pupil of Form 2 B handed me at school a letter which I was to hand over to the head prefect… The contents of the letter read more or less as follows: "We as students of Phafeni [sic] Junior Secondary School we feel that the subjects that are taught in Afrikaans are difficult for us, because even the teachers who are responsible for these subjects, they are also difficult for them. They cannot teach them to the perfection. So we will be glad if the principal can call Mr De Beer so that we can explain to him." … He is the circuit inspector of the Zulu schools in Soweto. I took the letter to the head prefect, who ignored the letter as he claimed that it was too late for the students to complain about this. The students kept on asking me when they would get a reply to their letters on which I would reply that the principal was still trying to solve the problem.

[…]

On a Monday following this episode of the letter, it was still during May, 1976, just after all the students had attended the assembly, and were told to return to their classes by the principal, they stood firm. I could see the principal and the teachers were surprised at the action which the students followed up by raising placards which read: "We do not want social studies and mathematics in Afrikaans." The same wording was written on the back of the shirts of some of the students.107

[…]

The students also said that they wanted to see Mr De Beer, that is our circuit inspector. Our principal, Mr F. Simbulo then called me to the front where he handed to me a minute book which he claimed was a message from Mr De Beer. This was written in Afrikaans. As I started reading the message, I was shouted down by the students. I therefore discontinued the reading. Mr Simbulo then explained to the students that Mr De Beer could not come quickly, as he was in Pretoria. The students reacted by staying away from class for the rest of May, 1976.108

The evidence suggests that Seth Mazibuko was also the person who in effect linked the struggle that had already begun at the junior secondary schools with the political plans for a show of solidarity and for a broader protest, plans that came mostly from students from the high schools. At the meeting on Sunday, June 13, at which protest action against Afrikaans was considered by students from all over Soweto, Seth Mazibuko spoke for his school:109

He [the main speaker]110 also discussed the use of Afrikaans as a means of the tuition or language and called upon the prefects of our schools to come forward and to explain what the position was there. I stood up and told the congregation that the Phefeni School refused to use Afrikaans and they had boycotted the classes during May, 1976.111

When the action committee to organize the fateful protest march was elected, Seth Mazibuko was unanimously elected vice president. Later, as a member of the SSRC and SASM, he became one of the key leaders in the student movement.

Murphy (Mafison) Morobe was a student leader in 1976 and a member of SASM since 1974. Sixteen years after Soweto he remembered that, when the Afrikaans decision "first landed on our desk as the South African Students' Movement," it was

the key issue which … we had always looked for…issues around which to mobilize and get students to be involved and to be more aware of their situation as students in an Apartheid and Bantu Education environment. And when the issue was introduced in 1975, it was at levels whereby, it was introduced at the junior secondary and late, higher primary, like standard six and Form one, Form two, Form three. Now, we were at high school at that point doing Matric, and we were not directly affected by that issue. But I think that the extent to which it affected our people, the students and the teachers, was quite dramatic because we had students and teachers [student teachers?] coming to us complaining about the fact they are not in a position to teach mathematics in Afrikaans, physical sciences in Afrikaans, etc. But we looked at the underlying reasons for that and one of the key reasons was a desire on the part of the authorities to ensure that Afrikaans becomes the language of this country. And we saw it as being forced to learn through the language of what we considered to being the oppressor.112

Students did not always speak with one voice. Motapanyane, in the following quote, is apparently using some of the more dismissive characterizations of the Afrikaans issue ("the spark that fell on top of the powder keg"). It is important to note that he was speaking in an interview-quoted in the ANC's official newsmagazine, Sechaba113—after he had left South Africa and found his way into the protective fold of the ANC. He already spoke for the ANC at this point. Nevertheless, he, like so many, recognized the importance of the interconnectedness of Afrikaans and the larger context of oppression. He was also not blind to its connection, through the Department of Bantu Education, with the government:

The immediate issue was, as we know, the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction by Vorster's regime.80

[…]

Afrikaans was not the real issue. It provided the spark that fell on top of the powder keg that was building up amongst the African people as a whole. Afrikaans happened to be the immediate issue. The real issues are racism, oppression, and exploitation.114

"When the directive from the Bantu Education Department was issued that certain subjects should be taught in the medium of Afrikaans," Motapanyane said, the students reacted "very negatively." That negative reaction, and a realization of its potential force, was exactly what was needed by those leaders among the students who were looking for a cause around which to organize:

We were channelling the anger. And I think for us, a demonstration was the notion that immediately came to mind. But even as we thought of a demonstration, there continued to be memories of what happened in Sharpeville, even though in fact what happened subsequently June 16 was not really part of our plan, the students, but the fact that it happened was in itself at that point a reflection of the intensity of the situation on the ground.115

On June 13, the Sunday before the uprising, a quickly convened meeting of students from schools all over Soweto resolved not only to hold a march but to organize as many students as possible in the townships to rally to the cause. The action committee that was elected on Sunday, June 13, met again the next day in the afternoon to discuss the routes to be followed from the various schools. Murphy Morobe, who attended that meeting, also described how students there discussed the placards to be carried, and he listed some of the suggestions about what they should say:

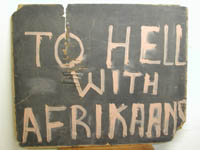

AWAY WITH AFRIKAANS.

AFRIKAANS POLLUTES OUR MINDS.

AFRIKAANS FOR AFRIKANERS.

AFRIKAANS RETARDS OUR PROGRESS.

He himself made and carried a placard reading "Away with Afrikaans" when he went to school the next morning.116 And when David Kutumela arrived at school on June 16 at about 7:45 A.M., he carried a placard, which he had made himself, that bore the same three-word message. Other students already standing and waiting in the schoolyard were also carrying placards. "Afrikaans is not an international language," one of them read.117 Tebello Motapanyane addressed the students and told them by which route they were to march to Orlando West school grounds. Tsotetsi, the vice principal, was chased away when he tried to address them:

After prayer [June 16] Mashinini shouted "Amandla," which means "Power." The students in return replied "Ngawethu"-meaning "us." Some students were wearing placards…

Away with Afrikaans

Weg is jy Vorster met jou Afrikaans [Away with you Vorster with your Afrikaans]

We are not ready for Afrikaans yet.118

Kutumela went forward after Motapanyane had finished, and he told the students that "they should move fast, hold the placards high and … I made a clenched fist and we all moved out of the school."119 Before students at Morris Isaacson High School left their school grounds to join the gathering march, they fastened to the fence of the school grounds a banner that tied Afrikaans not only to Bantu Education but also to broader issues of liberation: "We shall not use Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. The Department of Bantu Education is formed of ignorant fools. It happened in Angola. Why not here."120

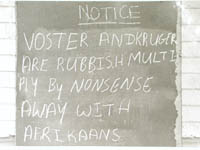

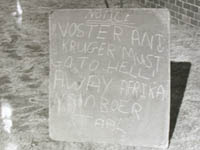

Not only did the banners and placards contain political messages, but even the materials and manner of their construction, with their origins and their multiple meanings, were eloquent. Made out of old shirts and torn-up flour or corn sacks, or with messages scrawled on the cardboard of grocery boxes or pieces of corrugated tin, the placards and posters were evidence also about the poverty and the strains of everyday life in the townships. During the first march, students displayed messages that directly addressed the Afrikaans issue:

AFRIKAANS MEANS CONFINED TO S. AFRICA85

WE SHALL NOT USE AFRIKAANS AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION

THE D.B.E. [DEPARTMENT OF BANTU EDUCATION] IS FORMED OF IGNORANT FOOLS

IT HAPPENED AT ANGOLA. WHY NOT HERE?121

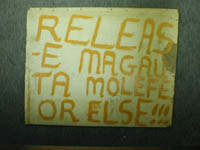

Over time the messages changed, as did the media. Slogans appeared on building walls and on the burnt-out shells of trucks that the students used as roadblocks, placing them in the middle of roads. New placards were made of doors and chalkboards ripped out of destroyed buildings and classrooms. In their diversity, these also reflected the many issues that preoccupied the students and revealed an awareness of interconnections. Spelling mistakes were clues to the failures of the education system, just as the eloquence of others highlighted the giftedness of some who sought to make their way through against great odds. And in time the issue they addressed changed to reflect the shifting agendas and targets of the uprising as well as its shifting moods.

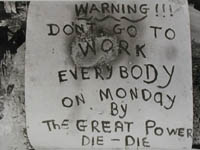

By September, several students had been detained and the SSRC called for a stay-away.

KRUGER RELEASE SETH MAZIBUKO

AZIKWELWA RELEASE ALL STUDENTS

WE ARE NOT FIGHTING PLEASE! RELEASE OUR BROTHERS AND SISTERS, WHO WERE ARRESTED AND DETAINED DURING "THE RIOTS" GILBERT MAZIBUKO122

Some were conciliatory, others were confrontational, angry, and even threatening.

DON'T PLAY, FIGHT SUPPORT SOWETO

VIVA SOWETO. THIS SHIT AFRIKAANS. COME PISS RAIN. SHIT A STORM. AMANDLA.

SOWETO: WHITE-DOMINATION, FEAR, MURDER

BLACK-REVOLUTION, POWER, FREEDOM

DON'T SHOOT AFRIKAANS INTO US123

When Henry Kissinger visited South Africa on September 17, 1976, police confiscated

See document:

Banner and Poster Slogans

and meticulously photographed and documented hundreds of placards from a demonstration they had broken up. Placards found on the

campus of the University of the North, in the northern Transvaal, also took up the cry against Afrikaans:

IF YOU KILL A KID—YOU CHALLENGE A NATION^top

HITLER IS ALIVE HE MUST BE DESTROYED

AWAY WITH THE FARM LANGUAGE

I BETTER BE A SERVANT IN HEAVEN (FREE AZANIA) THAN A KING IN HELL (WHITE SA)

WHY SHOOT INNOCENT KIDS?

AFRIKAANS A SHIT LANGUAGE. DOWN WITH THE SYSTEM

WHAT ARE BLACKS, SHOOTING TARGETS?

AFRIKAANS POISON

BOERS, GO AND FIGHT AT THE BORDERS

SOWETO TODAY—WHITES TOMORROW

AFRICA AND AFRIKAANS ARE MILES APART BEWARE AFRIKANERS

WE ARE SICK AND TIRED OF THESE PIGS TO HELL WITH THEIR STINKING AFRIKAANS124

Conclusion

"My Thoughts," a prose poem written by one of the student participants in the uprising, reflects the eloquence of an empowered thinking student consciousness:

We have been living through an unforgettable period. Here is history in the making, with all its terrific drama and all its tragic interest. For our age is transitional. Its very uniqueness prepares the way for a unique renaissance. We must learn to meet bad times with better thoughts. We must struggle for a new era characterised by heartfelt universality. It is for us to spell the riddle of the future with letters drawn from the alphabet of the present. It is for us to evaluate the movements disclosed by history and follow its own logic. It is for us to draw wise lessons out of the vanished centuries for our own ethical guidance and material profit.90

When intelligence is only partial, immature and incomplete, it leaves man cunning, selfishness and materialism. When full, mature and perfect, it teaches him wisdom, selflessness and truth.

Struggle there must be, for all life is a struggle of some kind.

For what man will not learn by reason he must learn by pain. He who will not think, must suffer.

Hatred is a sharp boomerang which not only hurts the hated but also the hater, they will hesitate twice and thrice before yielding to this worst of all sins.125

But for the outraged protests of the students, the "alphabet of the present," from which the author of this piece hoped to draw the letters for a new future, might have been in Afrikaans.

The negative assessment of the student movement, of its organizational capacity and power to effect changes, pervaded the literature. Kane-Berman called it the "turning point too soon," Hirson wrote of the "year of ash." Even Steve Biko, somewhat obliquely, referred to a need for "more careful planning and better calculation" that would allow "the desired results to a greater extent than this spontaneous situation we had last year."126 Kane-Berman described the "generalised nation-wide revolt" as a phenomenon utterly lacking a political will or historical actors, his language suggesting a mechanical, uncontrolled, inevitable escalation that had nothing to do with the people who stood at the center of it:

[I]nevitably, events gained a momentum of their own. The velocity of the chain reaction in other parts of the country suggests that these places were already volatile enough for the news of the shooting to be in itself sufficient to trigger off explosion there.127

From "the way anger and protest erupted throughout most of the Transvaal, and in several urban centres in the other three provinces, spreading much wider … and involving many who were not school students," Brooks and Brickhill concluded that the uprising was "a spontaneous response to the killing of the Soweto students on 16 June." By arguing, contrary to all the evidence they had presented to that point, that the uprising was "spontaneous," they undoubtedly sought to distance themselves from official analyses and commentary that had argued that the uprising was part of a conspiracy, one deliberately planned by communist and insurrectionary outsiders.128 In addition to creating the contradiction inherent in the two "sparks" they identified, Brooks and Brickhill, like Kane-Berman, conferred on the uprising the force of nature and wrested it out of the capable hands of the students at the center of it:

The shootings were the spark that ignited much wider frustrations and aspirations. There is no suggestion that a generalised rebellion was what the Soweto students intended when they launched their demonstration. Organization around a vital issue of the day and mobilisation in peaceful mass action had been the necessary elements in sparking off the uprising. Now "the situation" took over, and wider forces came into play.129

Despite Kane-Berman's own clear abhorrence of the "total situation in which black South Africans find themselves,"130 and despite the praise that Brooks and Brickhill express for the "courage, energy and organisational capacity of the black students,"131 these analyses, reflecting a shocking disregard for those who stood at the center of the uprising, recalled Steve Biko's reproach of most white liberals: "They forget they are talking about people. They see blacks as additional levers to some complicated industrial machine."132

Each discourse's appraisal of the causes of the uprising reflected the political agenda or ideological point of view of its proponents. It is probable that spokesmen of the state, interested in preserving the status quo, initially hoped that the focal point of the protests would remain Afrikaans, an issue that could be addressed with relative ease. Once it became clear that the uprising was either the result of causes that were more complex or that it had taken on a momentum beyond its initial focus, they necessarily argued that what they were facing was, rather than an indictment of the entire system of rule, a consequence of outside "communist" agitation or internal criminal disorder. The ANC, on the other hand, understood the uprising and its causes against the background of its hopes and plans for a more determined criticism of and mass challenge to the state. As became clear in Chapter 4, ("The Participants:" Dissent, Division, Difference—Solidarity) even among the students there was no single authoritative voice. The students not only recognized the state's discourses and methods but also set out to counter them. Just before the first anniversary of the uprising, Nina Sabela, in a set of handwritten notes for the SSRC, wrote:

We are also aware of the system's conspiracy: (1) To discredit present and past leadership with the hope of distracting the masses from the leaders. (2) To capture present leadership with the hope of retarding the student's struggle and achievements.13395

That students were extremely aware of the power of language and words was evident in their placing of the term riots inside quotation marks on one of the placards they carried during a later demonstration. They understood the threat of attempts by outsiders, especially the government, to disparage their movement, just as they understood the language of power.134

If we shift the perspective to place Afrikaans more centrally into this story, restoring its importance both as an event and as an analytical tool—if we allow for its enormous symbolic power, deeply linked to and inspired by Black Consciousness thought, and for its organizing power—then what we see is that Afrikaans was key to the uprising. The evidence is also suggestive that such a perspective would also allow for a reexamination of the direct influence of the Black Consciousness movement. If, as some have written, the Black Consciousness movement lacked focus and organization and was turned inward, then here, in Afrikaans, it had found a focus, a point of protest, a constituency (students) and a place (schools.)

At a more important analytical level, such a shift in perspective forces us to hear the voices of the students, for if we do not take Afrikaans seriously then we do not take the students' intelligence seriously: They understood Afrikaans to be symbolic for the entire system of Bantu education. If their complaints previously had been very general, now they had one issue that could stand for the whole system. They understood that as the "language of the oppressor," Afrikaans—the common experience of it and its relevance to their daily lives—would link the student movement to their parents and to the workers. They understood the implications of its implementation as proof of the illegitimacy of the state and of an attempt to exclude them from the economy and the international world. (This explains their vehement response to Kissinger's visit.) They also appreciated that their protests, petitions, and the march they had planned were legitimate ways to protest the implementation of this policy. The memory of Sharpeville was an old one—the threat of police retribution, which might have acted as a brake to their plans, was taken into account but not considered real in the students' imagination and experience.

Notes:

Note 97: Cillié Report, 1:63. back

Note 98: "To hell with Boere Taal," the quote in the title of this section, is from a placard carried by students (skoliere) demonstrating at Tlakula High School, 21 June 1976. Evidence no. 44, SAB K345, vol. 190. back

Note 99: Khotso S. Seathlolo, press release, 29 October 1976, evidence, SAB WLD 6857/77, WRAB v. Santam. Seathlolo took over as head of the SSRC (Soweto Students Representative Council) after Tsietsi Mashinini fled the country in August 1976. back

Note 100: Ibid. back

Note 101: Ndlovu, Counter-memories of June 1976, 12-14. back

Note 102: South African Students' Movement, Third General Students' Council, St. Ansgar's Conference Centre, Roodepoort, 28-30 May 1976, handwritten minutes; documents confiscated by the South African Police during the raid of SASM headquarters at 505 Lekton House, 19 October 1977, SAB WLD 6857/77, WRAB v. Santam, vol. 413. Also reprinted in Karis and Gerhart, From Protest to Challenge, 5:568-74 (document 65, "Minutes of the Annual General Students' Council of SASM (South African Students' Movement), Roodepoort, May 28-30 1976"). back

Note 103: Students of Hofmeyr High School, Atteridgeville/Saulsville, "Grievances Internally" and "External Grievances," memoranda, [find date], SAB K345, vol. 190, evidence no. 58. back

Note 104: Cillié Report, 1:43. back

Note 105: Students of Hofmeyr High School, Atteridgeville/Saulsville, "Grievances Internally" and "External Grievances," memoranda, [find date], SAB K345, vol. 190, evidence no. 58. back

Note 106: Prefects were elected or, more usually, nominated representatives of the student body at each school and acted as liaisons between the students and the teachers or principal. back

Note 107: Seth Sendile Mazibuko, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, pp. 4948-49. Seth Mazibuko remembered this day and declaration of protest again twenty years later in an interview for the television film, Two Decades… Still, June 16, film produced by Loli Repanis, directed by Khalo Carlo Matabane, for SABCTV, 16 June 1996: "It was in the morning of our usual open air assembly, after the usual praying and all that, the principal said to us, 'move into the classrooms. ' The students just stopped like that, scratched their feet on the ground, it is quite a gravel ground, you know, and after that took out our shirts, school shirts and underneath you will find another shirt, and that was the shirt that was written a slogan, you know, 'Away with Afrikaans,' and 'If you want us to do Afrikaans, you must also do Zulu. ' And take it further, placards that students had on that day, were hidden in the toilets of the school. It went on like that . . . and we stayed out of class." back

Note 108: Seth Sendile Mazibuko, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, pp. 4948-49. See also Biko, "Our Strategy for Liberation" (1977), in I Write What I Like, 147: "Now when these youngsters started with their protests they were talking about [exclusive use of] Afrikaans [in Black schools], they were talking about Bantu Education, and they meant that. But the government responded in a high-handed fashion, assuming as they always have done that they were in a situation of total power. But here for once they met a student group which was not prepared to be thrown around all the time. They decided to flex their muscles, and of course, the whole community responded. . . . " back

Note 109: The suggestion for a mass demonstration to be held on 16 June 1976, according to Mazibuko's testimony, came from Tsietsi Mashinini. Seth Sendile Mazibuko, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, Part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, p. 4950. This was confirmed by David David Lisiwe Kutumela, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, file 2/3, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, p. 4958. back

Note 110: Probably Tebello Motapanyane or Tsietsi Mashinini. In his statement Mazibuko identified him as "Aubrey" [Mokoena], but he himself corrected that, saying that it was written by the person taking down his statement during interrogation. See Essay-Winnie Mandela in Part 3 for a more detailed discussion of the process by which the statements of Mazibuko and others were obtained. back

Note 111: Seth Sendile Mazibuko, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, p. 4950. back

Note 112: Interview with Murphy Morobe, June 16, 1993, Radio 702 Talk Radio, interviewer: John Robbie. back

Note 113: Sechaba: "The African National Congress began publication of Sechaba in 1967. It documents the struggle, from the organisation's perspective, for freedom in South Africa and for the freedom of South Africa-freedom from racial discrimination, from legislation that denied human rights and from the Government's relentless policy of racially imposed injustice. Sechaba documents the process by which the African National Congress, banned in South Africa during the period 1961 to 1990, forged its struggle for freedom, justice and liberation despite being a banned organization" [my emphasis]. Southern African Freedom Struggles, c. 1950-1994, journal abstract, s. v. Sechaba, http://disa.nu.ac.za. back

Note 114: Tebello Motapanyane, interview, "How June 16 Demo Was Planned," in Sechaba 11 (second quarter, 1977): 58. back

Note 115: Murphy Morobe, interview by John Robbie, Radio 702 Talk Radio, 16 June 1993. back

Note 116: Mafison Morobe, unsigned statement, SAB K345 vol. 99, part 3, 3. See also Mafison Morobe, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, file 2/3, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 102, pp. 4898 and 4901. back

Note 117: David Lisiwe Kutumela, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, file 2/3, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, p. 4969. back

Note 118: Reatile Kingdom Lolwane, testimony, 10 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 104, p. 4988. back

Note 119: David Lisiwe Kutumela, testimony, 9 February 1977, SAB K345, vol. 148, file 2/3, part 19, Commission Testimony vol. 103, p. 4969. back

Note 120: Quoted in Cillié Report, 1:108, and photographed by police, SAB K345. back

Note 121: Photographs by Engelbrecht (captain, South African Police, Central Western Jabavu, 16 June 1976), and N. Steyn, reporter for Beeld (Phefeni), 16 June 1976, SAB K345, vol. 26. back

Note 122: Pressboard, 3 feet x 3 feet. Azikhwelwa means "don't ride"—i. e. , don't go to work. SAB K345, vol. 84, file 2/2/1/12/12. back

Note 123: Placards observed in Atteridgeville (near Pretoria), 17 June 1976 to 30 September 1976. Evidence, SAB K345, vol. 190. back

Note 124: Evidence, SAB K345, vol. 190, file 2/4, part 4. back

Note 125: "My Thoughts," unsigned, handwritten notes confiscated from Masabatha Loate at 7798 Orlando West by the police on 17 June 1977. SAB WLD 6857/77, WRAB v. Santam, vol. 436. back

Note 126: Biko, "Our Strategy for Liberation" (1977), in I Write What I Like, 148. back

Note 127: Kane-Berman, Black Revolt, White Reaction, 48. back

Note 128: Brooks and Brickhill, Whirlwind Before the Storm, 93. back

Note 129: Ibid. back

Note 130: Kane-Berman, Black Revolt, White Reaction, 48. back

Note 131: Brooks and Brickhill, Whirlwind Before the Storm, 2. back

Note 132: Biko, "The Quest for a True Humanity" (1973), I Write What I Like, 91. back

Note 133: Nina Sabela, handwritten notes for the SSRC, undated, evidence seized by South African Police, SAB WLD 6857/77, WRAB v. Santam, vol. 436. back

Note 134: RELEASE ALL / STUDENT DETAINED / AND ARRESTED / DURING THE / "RIOTS" [white chalk letters on what looks like a piece of chalkboard]. Collection of black-and-white photographs taken by police during the uprising in Soweto after June 16, 1976. , SAB K345, vol. 84, file 2/2/1/12/12. See also Nina Sabela, handwritten notes for the SSRC, undated, evidence seized by South African Police, SAB WLD 6857/77, WRAB v. Santam, vol. 436: "This recent proposal of imposing a rent increase upon Soweto residents without consultation is proof enough of the failure and futility of the Cillié Commission in exposing and showing the real underlying causes of the Soweto demonstrations, not riots." My emphasis. back