|

| |||

|

The least-studied area of non-military Soviet aid rendered to Republican Spain has been the evacuation of Spanish children to the USSR. | 1 | ||

|

The few exceptions to this paucity of scholarship on the evacuated children include two recent Spanish studies that draw on eyewitness survivor accounts and unpublished documents in various Spanish archives. 2 While these multi-authored histories make excellent use of the large correspondence between the evacuated Spanish children in the USSR and their families in wartime Spain, neither study incorporates any of the Soviet archival materials declassified after 1991. The most interesting Spanish work on the topic has been done by memoirists and filmmakers: here, the two autobiographical accounts by José Fernándo Sánchez stand out, 3 as does Jaime Camino's recent documentary film. 4 Among Soviet secondary sources, a single work is indispensable: V. A Talashova's 1972 doctoral dissertation on the role of the Komsomol in the Soviet humanitarian aid project for Republican Spain, which addresses in particular the establishment of a network of children's homes for the Spanish evacuees. 5 | |||

|

These Spanish and Soviet sources, taken together with hitherto unavailable documents and newsreels in the Russian archives, now make possible a more complete survey of the upbringing of Spanish children in the USSR and a fuller assessment of this episode's significance for Soviet-Spanish relations during the war. More important, the wealth of primary sources related to this issue now permits scholars to examine the myriad ways the Soviet regime exploited the refugee children for its domestic and international propaganda needs, while also attempting—not always successfully—to indoctrinate the children with a socio-political value system that diverged sharply from that of their homeland. | |||

|

Several scholarly accounts have adequately sketched the circumstances in civil-war-era Spain that necessitated the emigration of Spanish children to foreign safe havens. 6 Nonetheless, it may be useful to summarize these developments before examining the settlement and upbringing of the Spanish children in the USSR.

| |||

|

The Nationalist attack on Madrid in October 1936 was the first in a series of major confrontations that resulted in the displacement of tens of thousands of Spaniards who found themselves in the shrinking Republican zone. By the first week of November, Madrid's prospects were sufficiently bleak for the authorities to recommend a partial evacuation. The government itself soon fled to Valencia and, though many residents remained to defend the city, thousands of families left the besieged region for safer areas to the northeast. | 5 | ||

|

Madrid's fierce resistance forced Franco to repeatedly redirect his military operations during the first year of the war.  In early 1937, Franco turned his campaign south, capturing Málaga in the first week of February. The subsequent fall of large areas of the southern front forced a new wave of emigration; as before, those fleeing looked to the northeast for safety. 7 A new shift in Franco's strategy followed in March 1937, when the rebel leader turned his attention to the northern coast, in particular to Cantabria, Asturias, and the Basque provinces. This campaign featured the participation of the German Condor Legion, whose aircraft were responsible for the 26 April raid on the Basque market town of Guernica. In early 1937, Franco turned his campaign south, capturing Málaga in the first week of February. The subsequent fall of large areas of the southern front forced a new wave of emigration; as before, those fleeing looked to the northeast for safety. 7 A new shift in Franco's strategy followed in March 1937, when the rebel leader turned his attention to the northern coast, in particular to Cantabria, Asturias, and the Basque provinces. This campaign featured the participation of the German Condor Legion, whose aircraft were responsible for the 26 April raid on the Basque market town of Guernica.

| |||

|

The main exodus of Spanish children to the USSR and other locations in Europe began in earnest in late spring and summer 1937. Months earlier, however, Soviet authorities were already planning for the eventual reception of an undetermined number of Spanish war orphans. From its earliest stages, Soviet humanitarian relief to the Republic had granted special dispensations for children. On five separate occasions between 9 September and 16 October 1936, the Central Committee approved decisions authorizing various kinds of aid to children in Republican Spain. 10 In addition, on 22 September 1936, the Comintern Secretariat submitted a letter to Stalin with the request that he allow Spanish children to be admitted to the USSR. 11 At the same time, from 15 September to early October, the Soviet press issued numerous calls for increased assistance to Spanish war orphans. Editorials in Pravda, Izvestiia, and Literaturnaia gazeta suggested that Spanish children residing in areas of combat be evacuated to the Soviet Union. 12 | |||

|

Stalin's response to the Comintern request of late September is not known. It is clear, however, that at approximately the same time, the Mezhdunarodnaia Organizatsiia Pomoshchi Bortsam Revoliutsii (International Organization for Assistance to Revolutionary Fighters; hereafter, MOPR) undertook the preparation of a special home for foreign children on the Yaroslav rail line near Moscow. 13 With the pomp and circumstance that would later be de rigueur at the openings of all future Soviet homes for Spanish children, the 24 November 1936 official inauguration of the new institution was a gala event for the Comintern leadership; the highest offices of the international Communist organization were represented, and both Dimitrov and Togliatti delivered speeches. 14 Whether the Comintern letter of the previous month paved the way for the opening of the children's home or its construction was the result of emigration to the USSR by many communist exiles from fascist Europe, it is evident that a new level of mobilization vis-à-vis the question of refugee children was taking place by fall 1936. | |||

|

At the time of Manuilskii's September 1936 letter to Stalin, the impending refugee crisis in Republican Spain was still some months off, and the northern front of the war was yet to be opened. Between late September and December 1936, however, there occurred a general shift in the Soviet attitude towards the Republic—a change best exemplified by the acceleration of the solidarity campaign and the sudden increase in Soviet military aid to the Republic. In late October, for example, within weeks of arriving in Moscow, Republican ambassador Marcelino Pascua reported to his government that he had received numerous Soviet offers to take in Spanish war orphans. 15 Also indicative of the regime's augmented interest in Spanish affairs is a letter to Stalin from Red Army chief Voroshilov. Dated 20 December 1936, the dispatch is the second documented entreaty to the Soviet leader to begin accepting Spanish children into the Soviet Union. | |||

| 10 | ||

|

Voroshilov's letter was quickly acted upon. Two weeks later, on 3 January 1937, the Politburo approved decree no. 45/67, which authorized the Red Army Intelligence Service (Razvedupravleniia RKKA) to establish the first in a series of special homes for Spanish children. 17 | |||

|

Parallel to the Politburo's actions regarding the Spanish refugees were similar proposals and decrees put forward by the Comintern. Let us recall that at ECCI sessions between late December 1936 and autumn 1938, the Comintern decreed that the national parties should undertake campaigns of support for the Spanish Republic. Throughout the war, Comintern-directed solidarity and relief aid placed particular attention on the problem of refugee children and other non-combatants. The ECCI decision issued on 3 October 1937 indicated the breadth of the intended relief operation: | |||

| |||

|

Between March 1937 and December 1938, five separate expeditions brought approximately three thousand Spanish children to the USSR.  The first voyage, probably carrying seventy-two Spanish children, departed Valencia on 21 March aboard the Cabo de Palo and arrived the following week, on 28 March, in the Black Sea port of Yalta. 19 The second group was much larger, and comprised approximately fifteen hundred youngsters. Aboard a French vessel, the Sontay, the Spaniards departed Santurce on 13 June and arrived in Leningrad on 24 June. 20 The third expedition left Gijón on 24 September and included some eleven hundred children. The first voyage, probably carrying seventy-two Spanish children, departed Valencia on 21 March aboard the Cabo de Palo and arrived the following week, on 28 March, in the Black Sea port of Yalta. 19 The second group was much larger, and comprised approximately fifteen hundred youngsters. Aboard a French vessel, the Sontay, the Spaniards departed Santurce on 13 June and arrived in Leningrad on 24 June. 20 The third expedition left Gijón on 24 September and included some eleven hundred children.  After a number of preliminary stops and changes of vessel, on 4 October the group arrived in Leningrad aboard two Soviet craft, the Kooperatsiia and the Feliks Dzerzhinskii. 21 In 1938, two smaller boatloads of Spanish children called at Leningrad: 74 aboard the Mariia Ulianova on 12 July, 22 and 117, again aboard the Feliks Dzerzhinskii, on 6 December. 23 On all voyages, the children were accompanied by a support staff, which included escorts, teachers, nurses and doctors, and representatives of the Spanish regional authorities. After a number of preliminary stops and changes of vessel, on 4 October the group arrived in Leningrad aboard two Soviet craft, the Kooperatsiia and the Feliks Dzerzhinskii. 21 In 1938, two smaller boatloads of Spanish children called at Leningrad: 74 aboard the Mariia Ulianova on 12 July, 22 and 117, again aboard the Feliks Dzerzhinskii, on 6 December. 23 On all voyages, the children were accompanied by a support staff, which included escorts, teachers, nurses and doctors, and representatives of the Spanish regional authorities. | |||

|

To be sure, these numbers may be subject to future revisions. A review of unpublished Spanish and Soviet records, contemporary press accounts, and works of scholarship reveals some disagreement regarding the logistics and total numbers of children involved in the evacuation. One Spanish observer with close knowledge of the evacuation operation asserted in 1939 that just two thousand Spanish children were living in the Soviet Union. 24 A February 1938 report by the Barcelona chapter of the Amigos de la Unión Soviética (AUS) claims, that in the first three voyages, 2677 Spanish children were taken to the USSR: 70 in the March sailing, 1538 in June, and 1069 in September. 25 Curiously, an AUS publication several months later increased the total number to 2,690. 26 Zafra refers to four separate trips, ferrying 2895 children: 72 in March, 1495 in June, 1100 in September and, finally, 300 in late October 1938. 27 Tolmachaev's dissertation refers to five distinct voyages, transporting a total of 2868 children: in 1937, 72 in March, 1505 in June, and 1100 in September; in 1938, 74 in July and 117 in December. Hugh Thomas, whose work has led the field for four decades, is well off the mark, citing a total of 5000. 28 Further complicating the issue is an official Soviet count, published in 1977, which claims a total of 2848 children. 29 Talashova, whose numbers are quoted in Ribalkin, Novikov, and other post-Soviet Russian accounts, asserts that approximately 4000 Spanish children were eventually brought to the USSR. Without any specific evidence, Talashova estimates that as many as 1000 children arrived in late 1938 or early 1939. The figure of 4000 is probably excessive, yet it has appeared elsewhere, including in at least one Francoist source published shortly after the war. 30 In any case, when this last undocumented group of 1000 children is subtracted, we are left with a number similar to that in Zafra, and that is supported by the archival and press accounts: I find the rounded number of 3000 satisfactory, if not final. 31 | 15 | ||

|

The logistics of transferring this large number of Spanish children some 4000 kilometers required the cooperation of Spanish, French, and Soviet officials. As stipulated by the Politburo decree of 3 January 1937, Red Army Intelligence supervised all aspects of the voyage. In a letter to Voroshilov dated 12 June 1937, General Jan Berzin described the Red Army's role in the second and largest of the five voyages: | |||

| |||

|

Upon arrival in the Soviet Union, the children were greeted by an enthusiastic (albeit carefully orchestrated) display of solidarity. According to the Soviet press, the June 1937 expedition was escorted into the port of Leningrad by a flotilla of submarines and other vessels.  As the ship approached the docks, the Spanish children on deck were cheered by scores of well-wishers, whose numbers included local and national figures. The welcoming committees were headed by Komsomol and Pioneer leaders who had been individually nominated by Party and Komsomol officials in Leningrad and Moscow. As the ship approached the docks, the Spanish children on deck were cheered by scores of well-wishers, whose numbers included local and national figures. The welcoming committees were headed by Komsomol and Pioneer leaders who had been individually nominated by Party and Komsomol officials in Leningrad and Moscow.

| |||

|

Their relief at the end of the voyage was also accompanied by the children's first awareness of the totalitarian nature of their adopted land.  Apart from the flags and brass bands, at least one child was struck by the vast sea of identical portraits held aloft by many of those who had come to greet them. This was Stalin. He was an omnipresent force throughout the USSR, yet at the moment of debarkation he was for the Spanish children no more than "the man with a mustache." 37 Apart from the flags and brass bands, at least one child was struck by the vast sea of identical portraits held aloft by many of those who had come to greet them. This was Stalin. He was an omnipresent force throughout the USSR, yet at the moment of debarkation he was for the Spanish children no more than "the man with a mustache." 37 | |||

|

Following this heady reception, the children were taken ashore for processing. Local authorities were charged with bathing the children and inspecting them for signs of disease; the sick ones—not a few were infected with tuberculosis—were separated from the main group and promptly sent to convalesce, usually in the warmer southern climate of Crimea.

| 20 | ||

| |||

|

With these formalities out of the way, the children were sent to temporary lodging while their specially prepared homes were completed.  In the case of the earliest arrivals, those in March and June 1937, the children were required to spend several months in Soviet rest homes or pioneer camps. These intermediate accommodations tended towards the luxurious. The March 1937 group was initially taken to Artek, one of Ukraine's oldest spa towns. Here they resided for several weeks, enjoying the amenities of the locale, before being sent on to permanent lodgings in Moscow. 39 Similarly, those arriving in October of the same year spent their first nights in Leningrad's finest residence, the nineteenth-century Astoria Hotel. The children ate in the hotel restaurant, serenaded by a local orchestra that had learned one—but only one—popular Mexican (Mexican!) tune, "La Cucaracha." In the case of the earliest arrivals, those in March and June 1937, the children were required to spend several months in Soviet rest homes or pioneer camps. These intermediate accommodations tended towards the luxurious. The March 1937 group was initially taken to Artek, one of Ukraine's oldest spa towns. Here they resided for several weeks, enjoying the amenities of the locale, before being sent on to permanent lodgings in Moscow. 39 Similarly, those arriving in October of the same year spent their first nights in Leningrad's finest residence, the nineteenth-century Astoria Hotel. The children ate in the hotel restaurant, serenaded by a local orchestra that had learned one—but only one—popular Mexican (Mexican!) tune, "La Cucaracha."  40 Compared to the standards of wartime Spain, the children also ate quite well, with many bulking up considerably, and a few gaining as much as eight kilos. 41 In letters home, many singled out the food as their favorite aspect of life in the USSR. Others were somewhat dubious, though not unappreciative, of the Russian diet. Wrote one youngster to his mother: "They gave us bread with cheese and butter and something that none of us liked but which they told us cost a lot of money. Later, they gave us potatoes and cod, which were very tasty...." 42 40 Compared to the standards of wartime Spain, the children also ate quite well, with many bulking up considerably, and a few gaining as much as eight kilos. 41 In letters home, many singled out the food as their favorite aspect of life in the USSR. Others were somewhat dubious, though not unappreciative, of the Russian diet. Wrote one youngster to his mother: "They gave us bread with cheese and butter and something that none of us liked but which they told us cost a lot of money. Later, they gave us potatoes and cod, which were very tasty...." 42

| |||

|

The Spanish children were eventually accommodated and brought up in a network of children's homes created specifically for the young war refugees. According to the decision of the Politburo in January 1937, the homes were initially managed by Red Army Intelligence, but in November of that year their direction was turned over to the People's Commissariat for Education (Narkompros) of the Republic of Russia (RSFSR). 43 The overseeing bodies, first Red Army Intelligence and then Narkompros, worked in collaboration with other Soviet ministries and organizations in caring for the children. These included the People's Commissariat of Health (Narkomzdrav), the People's Commissariat of Defense (Narkomoboron), the aforementioned MOPR, the Leningrad and Moscow Party committees, the All-Union Leninist Youth Organization (Komsomol), and the Communist Pioneers. | |||

|

As with the other political, cultural, and military dimensions of Soviet involvement in Spanish affairs during the civil war, the care of the Spanish children was a project whose every significant facet was directed by the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The Politburo had the first and last word on all aspects of the children's homes, from their geographic placement to their bureaucratic structure, the supervising personnel assigned to them, and the cultural-political content of their educational curriculum. 44 These policies were laid out in Politburo meetings and passed on to the responsible ministry. The archives of Narkompros preserve a number of these Central Committee decisions, the most important of which are the "Regulations concerning the children's homes for Spanish children" 45 and the later directive for the operation of homes for Spanish young adults, "Regulations concerning the homes for Spanish youth." 46 | |||

|

The first permanent home for the Spanish children, like all those that followed, was assigned a quintessentially Soviet name: Spanish Children's Home No. 1. 47 The home, located on Moscow's Bolshaia Pirogovskaia, was a renovated nineteenth-century palace; it would later become the embassy of Vietnam. According to documents in the GARF II archive, the seventy-two children from the March sailing moved into No. 1 on 15 August 1937. 48 Its official opening, however, attended by a select list of invitees and well covered in the press, came six weeks later, on September 30. 49 | 25 | ||

|

In the fall of 1937, the establishment of new children's homes proceeded rapidly. Indeed, on 1 October, the morning after the official inauguration of the first home, No. 2 was opened in the Moscow suburb of Mozhaisk; 50 at the outset, No. 2 hosted 276 children. 51 Five other children's homes were opened in the Moscow environs over the course of the next two years. 52 The largest of these was No. 5, located in a wooded setting near the Obninskaia station on the Moscow-Kiev rail line. 53 Initially, its rolls included 436 children of preschool and school age, though by early 1941, its numbers swelled to over 500. 54 | |||

|

Leningrad and the surrounding region was the site of four homes for Spanish children. Two of these were urban residences, placed in the center of the former capital; the other two were rural and secluded, near the village of Pushkin. The country homes were established specifically for the youngest children, all of preschool age. 55 In the city, the Spanish children were given prestigious addresses: Home No. 8 was located at Tverskaia Ulitsa, 11; Home No. 9 at Nevskii Prospekt, 169. In Leningrad, as in the other large Soviet cities hosting the Spanish refugees, the children's homes were not large enough to serve as both living quarters and educational facilities. For this reason, most Spanish children living in cities attended Soviet schools, where special classrooms were set aside for their use. By contrast, in rural settings the children's homes usually had ample space for classrooms and other pedagogical activities. | |||

|

In Ukraine, six homes for the Spanish children were established from 1937-39. 56 The largest was home No. 13 in Kiev, organized towards the end of 1937, and occupied by 200-220 children. 57 Two other homes were situated in Kharkov and Kherson. 58 Ukraine also hosted three special homes for sick or convalescing Spanish children. Located on the Crimean peninsula, these sanatoria had facilities to house several hundred children at a time. 59 Two were located in Odessa, a third in the village of Evpatoria. 60 It was to the balmier southern climate of Crimea that Spanish children afflicted with tuberculosis were sent to recuperate, or, on occasion, die. | |||

|

As the children grew older, the need arose to create a new institution: the above-mentioned homes for Spanish youth, or young adults. Two of these were eventually opened, one in Moscow and another in Leningrad. Each home housed 145-150 Spaniards, most in their late teens. 61 These individuals had completed seven grades of primary and secondary schooling and passed the required examinations. As residents of the young adult homes, many took day jobs in factories while continuing their studies in the evening. Opened first in 1940, the young adult homes had a short life span, as the coming of war in 1941 forced their evacuation and closure. | |||

|

Between August 1937 and the end of 1940, Narkompros oversaw the creation of twenty-two homes for Spanish children. As we have seen, two were specifically for young adults, while three others were designed for ill or convalescing children. 62 The geographical placement of these homes is a point worth examining. Let us recall that the late 1930s was an era during which hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens were being forcibly sent to the less hospitable regions of north-central Russia, and an equal or greater number of others languished in forced labor camps. By contrast, the locations given to the homes for Spanish children seem strikingly charitable. Approximately a third of the homes were placed in Moscow, Leningrad, or Kiev—by Soviet standards, vibrant cities with abundant cultural resources and diversions. Most of the others were located in forests, near rivers or lakes or, in the case of the three sanatoria, by the sea. Put another way, the Spaniards living in the USSR were settled in the very best areas available, far superior to those endured by most of the Soviet citizenry.

| 30 | ||

|

If their geographic placement offered certain advantages, what may be said of other aspects of the Spanish children's lives in the USSR—the curricula used in their education, the teachers engaged to instruct them, and their involvement in and awareness of the cultural-political milieu of Stalinist society?  Here as in other areas of their involvement with the Spanish Republic, the Soviet authorities pursued a multi-layered and often duplicitous policy. On the one hand, the government of the USSR pledged that the Spanish children's Soviet sojourn would be temporary, and repatriation would follow the Republic's victory. Superficially, at least, both Soviet and Republican authorities took pains to ensure that the children's expected return to Spain would not be complicated by excessive culture shock. To facilitate eventual repatriation, the schooling of the Spaniards in the USSR was said to replicate as closely as possible their education in Spain. Here as in other areas of their involvement with the Spanish Republic, the Soviet authorities pursued a multi-layered and often duplicitous policy. On the one hand, the government of the USSR pledged that the Spanish children's Soviet sojourn would be temporary, and repatriation would follow the Republic's victory. Superficially, at least, both Soviet and Republican authorities took pains to ensure that the children's expected return to Spain would not be complicated by excessive culture shock. To facilitate eventual repatriation, the schooling of the Spaniards in the USSR was said to replicate as closely as possible their education in Spain. | |||

|

Not a few observers in the Spanish Republic called considerable attention to this seemingly benevolent policy. A report submitted in February 1938 by the Barcelona Amigos de la Unión Soviética asserted that "the educational material ... is the same as that in all national schools of Spain." The report goes on to insist that: | |||

| |||

|

In certain respects, there was some truth in the official and oft-repeated claims that the Spaniards' education closely resembled that which they would have received back home. All academic subjects, save Russian language study, were taught in Spanish. Furthermore, a large proportion of the instructors working with the children were Spanish nationals, brought to the USSR specifically for this purpose. Constancia de la Mora, whose daughter Luli was evacuated to Moscow, described the girl's Soviet education as follows: | |||

| |||

|

A closer examination of the pedagogical approach to educating the Spanish children in the USSR reveals that the institutions set up for the refugees could scarcely be called "Spanish schools," unless of course one acknowledges that some degree of sovietization was occurring simultaneously within the Republic's own system of public education. 65 Apart from the language of instruction, the schooling of the children adhered closely to the Soviet system of education. Though some teachers had arrived with the children from Spain, the majority were Soviet nationals who had been trained in Castilian to work with the children. 66 Textbooks, with almost no exceptions, were standard Soviet texts hastily translated into Castilian. 67 | 35 | ||

|

The Spanish Republic's Ministry of Public Instruction and Health considered this state of affairs unacceptable, and in mid-February 1938 it sent five boxes of instructional materials to the Moscow embassy. 68 Archival documents indicate that the embassy received the shipment on 29 April 1938, and immediately turned the materials over to Narkompros, the commissariat charged with running the schools for Spanish children. 69 Curiously, the problem of the children's access to Spanish pedagogical materials was not resolved. Two months later, in June 1938, the Republic's chargé d'affaires in Moscow, Vicente Polo, informed his government that the children still lacked Spanish books. "They are without Spanish grammar books," he complained, "and have no geography or history of Spain." He added that the Soviet government had recently supplied the schools with Spanish language versions of Soviet-authored histories and geographies of the USSR. 70 It requires no extraordinary investigative powers to deduce what had probably transpired. Having received the Spanish instructional materials from the Republic's embassy, the commissariat appears to have shelved these and distributed its own textbooks instead. | |||

|

Polo, apparently the children's only genuine advocate in mid-1938, appealed next to ambassador Pascua, formerly assigned to Moscow, now the Republic's lead man in France. By the end of November of that year, Pascua had received a new shipment of textbooks from Valencia, and these were dispatched from Paris to Moscow in early December. 71 Whether this set of books reached the evacuated children, or was again swallowed up by the Soviet authorities, cannot be determined from available archival documents. At any rate, the intractable difficulties of getting Republican-authored instructional materials into the hands of the evacuated children is highly indicative of the nature of the Spanish children's education in the USSR. | |||

|

That the children were increasingly subjected to Soviet educational norms is revealed in a 1938 pamphlet by Tomás Navarro Tomás, the director of the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, who had recently returned from a visit to the USSR. While acknowledging the authorities' intention to educate the children as Spaniards, Navarro Tomas observed that, "as they familiarize themselves with the language of the country, our little compatriots are being incorporated into the local educational system." 72 | |||

|

The best view of the Kremlin's aims regarding the children's education in the USSR may be gathered from the above-mentioned May 1937 Politburo policy directive, "Regulations concerning the children's homes for Spanish children," as well as the later order governing the operation of homes for Spanish youth. The documents state clearly the Central Committee's intention to give the Spaniards a thorough Communist education, to instill in them respect and esteem for collective work, and, in short, to make them "energetic builders of socialist society." 73 According to the first directive, one of the main foci of the children's upbringing must be to imbibe them with a "socialist love for labor in everything they do." 74 The Politburo orders make no mention of preserving Spanish national values or customs. | |||

|

It is perhaps surprising that no moderate or liberal elements of the Republican government stepped forward to prevent Stalin's regime from sovietizing the evacuated children. Yet the under-funding of the Republic's Moscow embassy, detailed above, kept Loyalist authorities largely in the dark regarding the state of the children's education. Pascua himself was quite troubled by this, enough at least to send his government a request in October 1937 for the appointment of a cultural attaché responsible for the inspection and monitoring of the evacuees. The response from Barcelona, delayed for weeks, was a half-hearted promise to forward the matter to the Minister for Public Instruction. 75 The Ministry's only apparent follow-up was to distribute photographs of the president of the Spanish Republic, along with instructions to hang these in the children's Russian classrooms. 76 | 40 | ||

|

The issue of monitoring was not raised again in the subsequent correspondence between the Moscow embassy and the Valencia/Barcelona governments. In fact, it fell to the ambassador himself—or his assistant, Polo—to visit and inspect the schools. Given the embassy's chronic staff shortage and the wide geographic separation between the children's homes, proper monitoring was all but impossible. 77 In any case, the Republic's disinterest in the nature of the children's education gave the Kremlin carte blanche to press forward with its own agenda. | |||

|

As a result, the Politburo decision that the education of the children be highly ideological in nature encountered no resistance, and was quickly and vigorously acted upon. As we will see, in nearly all aspects of the children's lives, whether at school or in leisure time, their Communist indoctrination was unrelenting. In a report to Narkompros, the director of one children's home discussed the mission of his institution this way: | |||

| |||

|

Even without these unpublished primary sources, the experiences of the children themselves published elsewhere have made clear the ideological orientation of their Soviet upbringing. Indeed, the Zafra study stresses the essential Communist nature of the Spanish children's education, which extolled the virtues of work, the superiority of the collectivized farms or worker-controlled factories, the importance of sexual equality, the rejection of all religion, and, above all, the concept of solidarity among the builders of socialism. 79 | |||

|

To achieve the ideological goals, which were made explicit in the initial directives for the upbringing of the Spanish children, the Politburo and Narkompros enlisted the aid of the major Soviet youth organizations, the Komsomol and its junior auxiliary, the Communist Pioneers. According to unpublished official documents in GARF II, only the most loyal and trusted members of these organizations were recommended for assignment to the homes for Spanish children. 80 The principal Central Committee directive regarding the upbringing of the Spaniards, the "Regulations concerning the children's homes for Spanish children," stipulates that all Soviet employees of the homes must be drawn from the Komsomol organizations and approved by their regional committees. 81 Moreover, the Communist Party apparatus maintained tight control over the Komsomol leaders whom they chose to work with the Spanish children. In fact, the Politburo recommended that, in order to ensure that its operating directives were fulfilled, the performance of the Komsomol workers be reviewed once a month. 82 | 45 | ||

|

Despite the painstaking selection process and subsequent vigilant monitoring, it appears that the final assignments still left much to be desired. Many of those selected were loyal Communists, but they had never worked with children and were often seen as an impediment to the successful operation of the children's homes. In a letter to Narkompros, the director of one Moscow-area home complained that the Komsomol workers assigned to him "have insufficient experience working with children ... and as a result their performance in the children's home cannot be considered very good." 83 | |||

|

Their lack of pedagogical experience notwithstanding, and against the protests of an occasional functionary, the Komsomol workers assigned to the children's homes largely dictated the cultural-political orientation of the Spaniards' upbringing and carried out the Politburo's order for full Communist indoctrination. This was accomplished in several ways. In the first place, Komsomol and Pioneer representatives enlisted a majority of the young Spaniards as members of the organizations themselves. Of the 467 Spanish pupils residing at Children's Home No. 5, for example, a total of 407 children, or 87 percent, joined the junior party organizations: 362 in the Pioneers and 45 in the Komsomol. 84 Elsewhere the proportions were comparable, if not as consistently high. At Home No. 12, 106 out of 137 pupils enlisted 85; at Home no. 10, 72 out of 131. 86 By the end of 1938, out of a probable total sum of between 2700 and 3000 refugees then living in the USSR, 1739 Spanish children were on the rolls of Soviet Communist Party organizations. 87 | |||

|

Recruiting children for youth organization membership was only the first stage in a carefully planned Communist upbringing. Komsomol workers, together with Soviet pedagogues, oversaw a wide range of activities that together reinforced the pro-Soviet and pro-Communist direction of the Spaniards' education. Indeed, despite the presence at the children's homes of many Spanish teachers, the educational plan was to a great degree controlled by Komsomol leaders. In fact, all teaching plans were dictated entirely by the Komsomol executive committee, though always with the review and approval of the Politburo. 88 | |||

|

Excepting the less ideological subjects of arithmetic, orthography, and biology, much of the school curriculum adhered to Soviet models. All children, even toddlers, were required to study the Russian language. Great stress was also placed on the history of the Soviet Union, which invariably included major forays into the biographies of the leaders of the October Revolution, the Russian Civil War, the Five-Year Plans, and careful readings of the Stalinist Constitution. 89 According to Talashova, once each week the Spanish children were required to listen to broadcasts or recorded speeches of Soviet leaders, in addition to reading assignments on the socialist construction of the USSR and the worldwide labor movement in current newspapers and journals. 90 Finally, the Politburo and the Komsomol executive committee recommended that all pupils take a course in the history of the Komsomol itself, as way of encouraging their membership in the organization. 91 | |||

|

At the same time, treatments of Spanish history concentrated on Soviet-style conceptions of the Spanish labor movement, with special attention paid to the 1934 Asturias uprising; the 1936 unification of Spanish socialist and communist youth organizations; hagiographic studies of José Diaz, Dolores Ibárruri, and other key figures in Spanish communism; and mythic representations of the young martyrs of the civil war, the most significant of whom was Lina Odena. 92 The children also celebrated as a holiday April 14, the anniversary of the 1931 declaration of the Second Republic. 93 | 50 | ||

|

In addition to classroom indoctrination, Komsomol workers accompanied the Spanish children on frequent extra-curricular excursions, all of which were designed to reinforce the ideological lessons taught at school. They took frequent field trips to factories, collective farms, and other sites of the socialist economy, and they queued up alongside Soviet youngsters at the Museum of the Revolution and the Lenin mausoleum. 94 The Spanish children also attended and actively participated in the myriad jubilees and anniversaries that dotted the Soviet calendar. They marched in parades celebrating Constitution Day, Election Day, International Youth Day, Constitution Day, International Women's Day, International Workers' Day (May Day), and the twentieth-anniversary celebrations of the Red Army, the Komsomol, and the October Revolution. 95 Moreover, the Spanish children did not merely show up to observe these festivities; they were often at or near center stage. Outfitted in blue worker-overalls, red neckerchiefs, and matching caps, the Spaniards attracted the attention of adoring Soviet crowds. Their presence, and the responses they elicited, were carefully recorded by the Soviet press. 96 On some occasions, such as the 1938 commemorations marking the twenty-first anniversary of the Revolution, state filmmakers were dispatched to create special newsreels documenting the children's appearances. 97 | |||

|

It is clear from the collection of unpublished letters sent by the children in the USSR to their families in Spain, written between 1937 and 1939, that the ideological content of their upbringing had a profound impact. Many of the letters—some from children as young as six or seven—are decorated with the hammer and sickle.  Not a few children ended their letters with exuberant, pro-Soviet exclamations: "ˇViva Rusia!" or, more often, ˇViva la URSS!", "ˇViva el Ejercito Rojo!", and, occasionally, ˇViva Stalin!" No child signed off with the discouraged "Adiós"; rather, they wrote, "ˇSalud!", or "ˇSalud, camaradas!" More than a few of the children seemed genuinely delighted by their new home; they breathlessly described their tours of Leningrad and Moscow, or their first viewing of Lenin's mummy at Red Square. 98 Not a few children ended their letters with exuberant, pro-Soviet exclamations: "ˇViva Rusia!" or, more often, ˇViva la URSS!", "ˇViva el Ejercito Rojo!", and, occasionally, ˇViva Stalin!" No child signed off with the discouraged "Adiós"; rather, they wrote, "ˇSalud!", or "ˇSalud, camaradas!" More than a few of the children seemed genuinely delighted by their new home; they breathlessly described their tours of Leningrad and Moscow, or their first viewing of Lenin's mummy at Red Square. 98 | |||

|

Though all of this may lead one to believe that the Kremlin's "Regulations" had been successfully implemented, a caveat at this juncture is necessary. As in other facets of Soviet-Spanish relations, the Politburo's policies did not always yield the intended results, and decrees did not guarantee success. Despite the regime's persistent attempts to indoctrinate the children, the ideological lessons were not enthusiastically swallowed by all. One child, José Fernández Sánchez, who arrived in Russia in October 1937, later recalled his first lesson in Soviet revisionist history. One day, his children's home was visited by a major figure in the Soviet armed forces, Marshal Egorov. The children already knew Egorov through his photograph in their history book. The marshal had come to inspect the conditions at the orphanage. He was mostly satisfied, apart from the blankets on the beds, which in his opinion were too thin for youngsters accustomed to balmy Southern Europe. Several days later, the children received warmer blankets, a gift from Egorov. It was not long after this that the marshal was denounced as an enemy of the people, and Fernández Sánchez, together with the rest of his class, was required to perform what had become a common ritual: clipping Egorov's photo from the textbook. The forced removal of his benefactor's portrait repulsed the young Fernández Sánchez, and contributed to his gradual disillusionment with his adopted home. 91 | |||

|

A certain amount of resistance notwithstanding, in their curriculum and daily activities the Spaniards were given a model Soviet upbringing. At the same time, the children's foreign provenance, their celebrity status, and the inordinate attention they received from numerous Soviet agencies all contributed to the atypical and even extraordinary nature of their lives. The most conspicuous evidence of this was in the very large number of caregivers they were assigned. While no comparable figures are available for homes of Soviet children, by any standard the authorities doted on the Spaniards with what can only be called excessive care and surveillance. In September 1937, for example, Spanish Children's Home No. 1 had on its rolls 84 children and a staff of 74 100; in January 1938, Home No. 2 had 276 children and a staff of 168 101; in early 1939, Home No. 5 had 457 children and a staff of 243. 102 In no instance apparent in the archival record did the staff-children ratio drop below 1:2; more often, it was closer to 2:3, or even 3:4. When the Spanish diplomat Vicente Polo visited a Moscow-area children's home in May 1938, he found the youngsters "surrounded with every sort of attention." 103 The Loyalist press frequently highlighted the intensive attention given the children; an article appearing in Spain in August 1937 declared that "... we are struck again by the sincere care and affection in which they are surrounded, and the order and discipline that has been established in the homes." 104 | |||

|

In general, the Spanish children received more intensive adult care and a greater variety and quantity of amenities than the average Soviet child, to say nothing of those poor Spanish youngsters trapped in the shrinking Republican zone. During a visit with several of the evacuees, Louis Fischer wrote that "they seemed happy and fatter than most Spanish children" he had seen in recent months. 105 To further illustrate the point, José Fernández Sánchez noted that he and his classmates never found themselves without spare change while living in Russia. Either given to them by a teacher or older Soviet friends, the children always had enough kopecks to visit the corner candy stand for a caramel or other sweet. 106

| 55 | ||

|

At this juncture, it may be appropriate to observe the role of the evacuated Spanish children in Soviet propaganda. The refugees evacuated from war-torn regions of Spain to the safety of Soviet cities and towns were fortunate to be out of danger, but the Soviet regime had much to gain as well. The reception of Spanish children in the Soviet Union presented Moscow with an easily managed and endlessly exploitable propaganda subject. Quite apart from the clear humanitarian mission served in caring for the Spanish war refugees, the Soviet government took thorough advantage of the public relations possibilities presented by the arrival of the Spanish youngsters. As with many other aspects of the Soviets' humanitarian involvement with Republican Spain, the Kremlin fully appreciated the domestic and international propaganda potential of its aid to the children. | |||

|

On the domestic front, the arrival, reception, and subsequent upbringing of the Spanish children was the source of innumerable Soviet press and radio reports. 107 The general tone of domestic reporting on the Spanish war refugees was unwaveringly positive; no aspect of the children's stay in Soviet Russia was without the requisite song of praise and giddy superlatives. Thus the Spanish children were housed in the "best children's homes," their teachers were "the finest," and the food and clothing provided to them was the "best available." The value of this variety of propaganda, supported by frequent public appearances by the children as well as published photographs, cannot be overstated. Indeed, the cheery news of the young Iberians happily studying and playing within Soviet borders was not only a foil to the general gloom that enveloped Soviet society during the height of the Stalinist terror, but it also did much to counter an older though hardly forgotten problem which had plagued the Soviet republics from the early 1920s until the first part of the 1930s: the wave of besprizorniki, or "homeless children," a consequence of the general chaos and dislocation of revolution, civil war, hunger, and forced resettlement. The besprizorniki had for several years been an omnipresent and dangerous menace in every Soviet city until their eventual disappearance through mass arrests and deportations. 108 | |||

|

Internationally, too, the Soviets made the most of the Spanish children under their charge. In general, foreign reception of the Kremlin's official version of the evacuees' upbringing was strikingly uncritical, even naďve. Throughout the early 1930s various foreign visitors to the USSR had written extensively on the deceptive and manipulative nature of the Soviet state tourist agency, Intourist, which went to great lengths to provide visitors with a flattering—and always totally untypical—view of Stalin's Russia. Intourist ensured that visitors were housed in the most sumptuous accommodations, provided with only luxurious and comfortable transportation, and enjoyed limitless culinary delicacies in well-appointed dining rooms. Recently published travelogues had contrasted the standard Intourist itinerary with the harsh reality of living conditions for most Russians. It is therefore curious that in the hyperbolic reports of the Spanish children's reception in the USSR one finds not a hint of proper contextualization, nor any reference to the rich literature that had documented the dual standards. Indeed, in 1937, the same year as the largest refugee evacuations, André Gide had written derisively of his privileged treatment, which was indistinguishable from that of the Spanish children: | |||

| |||

|

Instead, the Republican press and its readership tended to accept at face value the testimonies of recent visitors to the children's homes. Even more important facilitators in this public relations campaign were the children themselves, whose letters home were nearly always replete with praise for their foreign benefactors. These letters—which the Soviet authorities expedited to assure delivery—can be assumed to have won the USSR a fair amount of support among Spaniards living in the Republican zone. The lives and activities of the Spanish children in the USSR were frequently treated topics in journals or pamphlets published by Moscow or one of its front organizations in Western Europe.  110 Through VOKS, Moscow also distributed photographs of the Spanish children at rest or play in their Soviet homes, or on field trips to well-known Russian landmarks. 111 These photographs played a central role in commemorations within Republican Spain of the twentieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution. 112 The Republican chapters of the Amigos de la Unión Soviética also used photographs of the children in their own propaganda. 113 110 Through VOKS, Moscow also distributed photographs of the Spanish children at rest or play in their Soviet homes, or on field trips to well-known Russian landmarks. 111 These photographs played a central role in commemorations within Republican Spain of the twentieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution. 112 The Republican chapters of the Amigos de la Unión Soviética also used photographs of the children in their own propaganda. 113 | 60 | ||

|

Moscow's most overt—and possibly most successful—attempt to exploit the Spaniards' experiences in the Soviet Union was the production and distribution of newsreels and short feature films on the children's homes and the general activities and lifestyle of the refugees. These films were widely distributed in both the Soviet Union and the Republican zone of Spain, and are mentioned frequently in the press and archival records. 114 It is interesting to note the differences between two of these films, Ispanskie deti v SSSR ("Niños Españoles en la URSS"), which was prepared for the domestic Soviet market, and Nuevos Amigos (1937), which was screened only in the Republic. | |||

The longer and more polished of the two is the twelve-minute Ispanskie deti v SSSR. Though presented as a documentary newsreel, in places the high production values, caption script, and soundtrack combine to give Ispanskie deti v SSSR the look and feel of a post-sound socialist musical. Though the film includes material shot in Spain by Soviet cameramen Roman Karmen and Boris Makaseev, it has less in common with their ambitious series K sobitiiam v Ispanii ("Sobre los acontecimientos de España") than with Soviet celebrations of life on the collective farm, such as Alexandrov's Volga-Volga (1938), Gerasimov's Komsomolsk (1938), or Pyriev's infectious pre-war classic, Traktoristy ("Tractor-Drivers") (1939). The longer and more polished of the two is the twelve-minute Ispanskie deti v SSSR. Though presented as a documentary newsreel, in places the high production values, caption script, and soundtrack combine to give Ispanskie deti v SSSR the look and feel of a post-sound socialist musical. Though the film includes material shot in Spain by Soviet cameramen Roman Karmen and Boris Makaseev, it has less in common with their ambitious series K sobitiiam v Ispanii ("Sobre los acontecimientos de España") than with Soviet celebrations of life on the collective farm, such as Alexandrov's Volga-Volga (1938), Gerasimov's Komsomolsk (1938), or Pyriev's infectious pre-war classic, Traktoristy ("Tractor-Drivers") (1939). | |||

|

In the film's opening sequence, a Republican militia banner is displayed with the hammer and sickle transposed across the top.  This image, overtly symbolizing the unity of the Republic and the USSR, gives way to footage of Franco's assault on Madrid. Brief scenes of urban destruction and widespread panic fade to close-ups of a dead child and a grieving mother. A caption now informs the viewer that, "thousands of children were evacuated from Spain to the USSR." The scene shifts to the Spanish north coast, where distraught parents are seen hustling their children towards a waiting ship. This image, overtly symbolizing the unity of the Republic and the USSR, gives way to footage of Franco's assault on Madrid. Brief scenes of urban destruction and widespread panic fade to close-ups of a dead child and a grieving mother. A caption now informs the viewer that, "thousands of children were evacuated from Spain to the USSR." The scene shifts to the Spanish north coast, where distraught parents are seen hustling their children towards a waiting ship. | |||

The apocalyptic images of a darkened and terrorized Spanish Republic soon give way to daybreak in sunny and tranquil Moscow. As the soundtrack segues to an upbeat march, a splashy and eye-catching circular wipe takes us to the station, where a euphoric local crowd is on hand to greet the Spanish refugees. The apocalyptic images of a darkened and terrorized Spanish Republic soon give way to daybreak in sunny and tranquil Moscow. As the soundtrack segues to an upbeat march, a splashy and eye-catching circular wipe takes us to the station, where a euphoric local crowd is on hand to greet the Spanish refugees.

| |||

In the next shot, the children have already been installed in their new residence at the Black Sea resort of Artek. The montage that follows continues to draw implicit comparisons between their Soviet sanctuary and war-torn Spain. In the next shot, the children have already been installed in their new residence at the Black Sea resort of Artek. The montage that follows continues to draw implicit comparisons between their Soviet sanctuary and war-torn Spain.  We are treated first to images of a calm sea and clear skies before alighting on the manicured grounds of the stately, tasteful edifice where the children now live. An onscreen caption informs the viewer that the Soviet state is devoting "great attention and care" to the Spanish children.

We are treated first to images of a calm sea and clear skies before alighting on the manicured grounds of the stately, tasteful edifice where the children now live. An onscreen caption informs the viewer that the Soviet state is devoting "great attention and care" to the Spanish children.

| 65 | ||

|

A trumpet call sounds, and the children are seen marching outside to begin a vigorous routine of daily exercise.  Again, the symbolism in the montage is striking: the children parading in laundered, bleached-white athletic uniforms; their orderly calisthenics performed on a boardwalk abutting the glass-like sea; the sky, per usual, cloudless. This segment over, the viewer soon finds the youngsters in the classroom, where they are receiving instruction in both Spanish and Russian. Again, the symbolism in the montage is striking: the children parading in laundered, bleached-white athletic uniforms; their orderly calisthenics performed on a boardwalk abutting the glass-like sea; the sky, per usual, cloudless. This segment over, the viewer soon finds the youngsters in the classroom, where they are receiving instruction in both Spanish and Russian.

| |||

|

Next the viewer is treated to an extended, expertly choreographed study of the children's recess hour.

| |||

|

Significantly, this short film on Spanish children in the USSR was produced for exhibition in the Soviet Union only. The extant copies contain only Russian captions; no Castilian version appears to have been produced. What is striking, if not necessarily surprising, in Ispanskie deti v SSSR is the prominent role of Stalin himself, and the implicit connection between the Soviet dictator and the rescue and nurturing of the Spanish war refugees. | |||

|

Nuevos Amigos, meanwhile, is more narrowly focused on the experience of the Spanish war refugees  at the Artek resort and their budding friendships with Soviet Pioneers of the same age. While the general treatment, mis-en-scène, soundtrack, and location shots in Nuevos Amigos are nearly identical to Ispanskie deti v SSSR, the former picture is intent on demonstrating to a Republican audience the essential Spanishness of the children's upbringing in the USSR. at the Artek resort and their budding friendships with Soviet Pioneers of the same age. While the general treatment, mis-en-scène, soundtrack, and location shots in Nuevos Amigos are nearly identical to Ispanskie deti v SSSR, the former picture is intent on demonstrating to a Republican audience the essential Spanishness of the children's upbringing in the USSR.  To this end, most references to Stalin, whether captions or graphic material, have been removed; his only visible presence is a brief shot of a poster filmed from a considerable distance. 115 On the other hand, a portrait of Dolores Ibárruri can clearly be seen hanging over the main door of the central mansion. To this end, most references to Stalin, whether captions or graphic material, have been removed; his only visible presence is a brief shot of a poster filmed from a considerable distance. 115 On the other hand, a portrait of Dolores Ibárruri can clearly be seen hanging over the main door of the central mansion.  In similar fashion, some pains are taken to show the viewer that the children's studies are being conducted in their native language. Several close-ups allow us to read the Castilian script on the covers of the school's textbooks. The viewer is even taken into the kitchen to meet the children's Asturian chef. In sum, the overall impression is that the children's Spanish heritage is being carefully preserved and reinforced. In similar fashion, some pains are taken to show the viewer that the children's studies are being conducted in their native language. Several close-ups allow us to read the Castilian script on the covers of the school's textbooks. The viewer is even taken into the kitchen to meet the children's Asturian chef. In sum, the overall impression is that the children's Spanish heritage is being carefully preserved and reinforced. | |||

|

Though destined for separate markets, both Ispanskie deti v SSSR and Nuevos Amigos sought to bolster domestic and international support for the Stalinist regime.

| 70 | ||

|

This conclusion, however undeniable given the celluloid evidence, should not allow for simplistic dismissals of the regime's use of the Spanish children. To be sure, while here and elsewhere the Soviet government's exploitation of the refugees is obvious, and would appear to have helped the Soviet regime to win back at least part of its tattered reputation as a champion of foreign workers and revolutionaries, two qualifying remarks are in order. First, the temptation to exploit the plight of those youngsters caught in the Spanish Civil War was too great for any of the involved governments to resist. Stalin's was neither the only nor the first regime to take advantage of the gift presented to them; in both the Nationalist and Republican zones, and among the international supporters of each, the suffering of children was highly politicized early on and throughout the war. 116 | |||

|

Second, the Soviet authorities must be credited with fulfilling a critical humanitarian mission. The propaganda coup aside, the Soviets were still left to deal with three thousand young foreigners, traumatized children who, as non-Russophones, required extraordinary care and resources. Most of the children were in a pitiful state upon arrival in the USSR. Many had no possessions save for the rags on their backs, and a majority were quite ill, many suffering from tuberculosis. Indeed, so many of the inhabitants of the second Spanish children's home were ill that, for its first six weeks of operation, the edifice was converted into an enormous infirmary. 117 Without a doubt, the project of nursing the sick and raising all the children was a demanding and costly one. Whether or not the Soviets themselves profited one way or the other, it would appear that the majority of Spanish children evacuated to the USSR fared extremely well. | |||

|

Furthermore, the education of the children, while not reproducing the conditions of Spanish schooling, and heavily propagandistic in its orientation, nonetheless served most pupils in a positive manner. Apart from heavy doses of ideology, the Soviets had much else to offer the children. The most valuable aspect of the Spaniards' education in the USSR was without a doubt the elective kruzhki, or "circles," which allowed each child to pursue a particular cultural or scientific activity as a serious hobby. In this manner, the Spanish children developed rewarding and potentially profitable skills in thirty-nine different areas, including photography, sewing, model airplanes, ballet, orchestra, jazz ensemble, drama, piano, and radio broadcast. 118 Some of these activities are depicted in Ispanskie deti v SSSR, and in all cases they appear serious, advanced, and well supplied and tutored. In addition, many of the Spaniards participated in after-school sports activities. Often they chose the Spanish favorite, soccer, though they were also able to try and become proficient in popular Russian winter sports, such as ice skating, skiing, sledding, and snow-shoeing. 119 Finally, the Spaniards spent their summer vacations in wilderness youth camps, usually interacting with Soviet children. 120

| |||

|

From the foregoing, several general observations might now be made. First, the experience of the Spanish children residing in the USSR was extraordinary and in no way characteristic of the way Soviet children lived in the late 1930s. The Spaniards' upbringing diverged sharply from both the Republican and the Soviet models. Be it through the high proportion of teachers and staff assigned to them, the wide range of their extra-curricular activities, or the comparative luxury they experienced in a place and era known for austerity, the Spanish children lived privileged lives. Moreover, their obvious good fortune was exploited by Moscow to win the Soviet regime sorely needed respect and praise both at home and abroad. | |||

|

These generalizations, however, require qualification if one considers the lives of the Spanish children in the USSR as the Spanish Civil War came to an end. Although from 1937 to late 1938 those Spanish children evacuated to the Soviet Union enjoyed a standard of living that far exceeded that experienced by the children they left behind in Spain, as well as nearly all the children living in the Soviet Union, as the war in Spain drew to a close Soviet interest in the orphans waned. By the middle of 1938, the Spanish war was no longer a cause célèbre in Soviet society, and yet the problem of the evacuees had no logical resolution. There was neither Soviet nor Republican support for repatriating them to a soon-to-be Nationalist Spain, and no third country stepped forward to offer refuge. The children and teachers had nowhere to go; Franco's impending conquest had stranded them in the Soviet Union. | 75 | ||

|

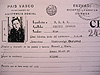

At least one Republican official assigned to the Moscow mission continued to lobby on behalf of the Spanish colony. In April 1938, Vicente Polo reported that many Spanish teachers had visited the embassy seeking repatriation. "In no case do they wish to remain here," Polo reported, "if we lose the war." 121 This point of view was not, however, universal. As the Nationalist victory appeared more inevitable, some continued to view the Soviet Union as a safe haven. In May 1938, the mother of two evacuated children instructed the Foreign Ministry to permit her son and daughter to remain in Russia, "so that they might be spared relocation to a potentially fascist country." 122 But this minority opinion aside, in preparation of eventual repatriation for those wishing to leave, Polo soon began issuing official identification cards and passports to the children and teachers resident in the USSR. 123 The chargé d'affaires assumed that the refugees' eventual return would require better personal documentation than that with which they had hastily left Spain. | |||

|

Polo's interest in the fate of the children and teachers received little support from the Loyalist government. Through the spring and early summer of 1938, he kept his superiors abreast of all developments regarding the evacuees. Polo visited several children's homes and assessed the students' welfare and their attitudes regarding their homeland. On one visit he was struck both by how much excitement his arrival generated—i.e., the arrival of a Spaniard—and the children's patriotic love for the Republic. 124 Yet Polo's expressed concern for the children (by mid-1938 he appears to have been the only Republican official seriously interested in their fate) was largely dismissed. Indeed, at one point Pascua instructed Polo to do nothing more than inform the Ministry of Public Instruction "every now and then" ("de vez en cuando") regarding the children's condition. The ambassador added coldly, "[The problem of the evacuees] has many facets, and it is advisable that you relieve yourself of that responsibility." 125 | |||

|

Later, in early 1939, Manuel Pedroso, the Republic's chargé d'affaires in Moscow until the end of the civil war, undertook to send back those children who were committed to returning to Spain. His attempts were entirely fruitless and ignored by both his own government and the Kremlin. When Pedroso met with Potemkin in the first week of February, he was disturbed to learn that the assistant commissar had nothing to say regarding the Spanish children. 126 In March, only weeks before the end of the war, he found not a single sympathetic ear in the Soviet government; indeed, he was not even granted a meeting. 127 In a letter to Pascua on 3 March, Pedroso discussed the futility of the children's predicament: | |||

| |||

|

With the embassy completely broke and virtually out of contact with the rapidly shrinking Republican zone, Pedroso had no plausible way to resolve the issue. | 80 | ||

|

The onset of World War II brought about the conclusive end not only to the Spanish children's position of prestige, but to any hope of quick repatriation. The vast strains placed on Soviet society at the onset of the German invasion rendered impossible the continuance of the special treatment of the young Spanish exiles. Like millions of other Soviets displaced by fighting on the Russian Front, the Spaniards were evacuated to Asiatic Russia. Once removed from their comfortable abodes near Moscow and Leningrad, the Spanish children were safe from the twin dangers of combat and occupation. Nonetheless, they quickly gave up any claims to privilege and celebrity. Thrown together with the Soviet multitudes scrambling to points east, the Spaniards were now refugees of a second war, but with none of the geo-political cachet of the Spanish struggle. Like millions of others, they now struggled to survive hunger, disease, and exposure. Their fate during World War II and after, and their difficulties in winning repatriation to Spain, is an area still awaiting further research, but it is beyond the scope of this study. 12 | |||

|

The portrait of Soviet humanitarian assistance emerging in this narrative is one of immense contradictions. Clearly, the USSR contributed significant humanitarian relief to the Spanish Republic, throughout the duration of Spain's civil war. Soviet aid was collected and delivered not only during the heady first months of the civil war, when the world's eyes were focused on Spain and when vigorous assistance would receive the greatest international exposure, but in 1938 and 1939, when much worldwide opinion had come to accept Franco's victory as a fait accompli. That the Soviet public and government refused to abandon the Republic after the high-water mark of international attention had passed is a measure of their undeniable entrenched commitment to the Loyalist cause. | |||

|

The successive humanitarian fund drives, which sought and succeeded in uniting much of the Soviet citizenry towards a common purpose, were a tremendous propaganda coup for the Stalinist regime. If the Soviet people could be moved to stage enormous displays of solidarity with a distant and beleaguered state, perhaps their own cataclysmic passage—through man-made famines, forced industrialization, the liquidation of entire classes, massive forced-labor projects, large-scale deportations and, most recently, the show trials of faithful party officials—might be tempered by a new appreciation of Soviet achievement and magnanimity. | |||

|

For Stalin, the Spanish Civil War was thus seen as an opportunity, not only on the international front, but at home as well. The relief campaigns for the Spanish Republic were transformed into another in a series of struggles against foreign and domestic foes stretching back to 1917. In the view of the Soviet leadership, the Spanish cause conveniently conjured up elements of previous unifying Soviet struggles. Like the Russian civil war, the avowed defense of the Republic focused on repelling foreign invaders and resisting foreign domination. Like the Five-Year Plans, the campaigns of solidarity successfully embraced the positive rhetoric of a cheerfully competitive fundraising drive. As in all earlier struggles, the new movement called for personal sacrifice from every man, woman, and—as noted above—child. | |||

|

The benefits of this campaign for the Soviet regime are easy to identify. First, the Soviet people came to believe that they were key actors in a popular and unified struggle, the advocacy of which reflected favorably on their entire society, citizens and rulers alike. More important still, even as the Soviet people responded enthusiastically to calls for displays of solidarity and voluntary donations, the Kremlin made certain that the impressive numbers from this nation-wide fund drive were published as widely as possible, so that the campaign would reap the benefits of positive press at home and abroad. Regardless of the outcome of the civil war, and whatever losses the Kremlin might incur in its military intervention in Spain, the carefully planned and executed solidarity campaign ensured that Stalinist regime could expect a victory of some variety, if only on the home front. | |||

| 85 | |||

|