|

| |||

|

Out of context, these lists present odd compilations of meaning, and they raise a number of questions. What, for instance, are weavers doing in a list of castes and religions? Are the "Curnams, Banians, and Weavers" not "inhabitants" of Mungalageery? How do "Bramins" fit alongside "Gumastahs," and what is intended by the "etc." there? With the help of context, the sense of these collections may evince itself. Yet lists, of course, are more than this, more than their meanings in particular contexts. Lists tell us about the makers of lists. Lists comprise categories, categories that are understood, used, and further developed by the creators of lists. This is how I intend to use lists in this work; with their inherent categorizing features, lists will help us understand category production by Indians. Two important modes of understanding lists will emerge in this study. One requires that we observe how types of lists change over time. Such an attack on lists will help us see how dominant groups have had to reshape their attempts at categorization. These lists change because, as was the case with the Indian Census, the center cannot control categories as easily as it would like. In fact, there is a tendency to begin an investigation of historical lists with the belief that they were a tool of the center, that they assisted in the organization, normalization, and categorization of whatever is to be controlled and kept in check (the census being perhaps the most notable of this type of list). As such, lists tend to be used by historians to explain the exercise of power from above. Yet this first approach does not tell us about the people purportedly being categorized. | 1 | ||

|

Fortunately, everyone makes lists. Thus the second, and more insightful, tack we will use to look at lists will be to examine lists produced by those who are not in familiar positions of power. When we are given a chance to explore lists and categories made by those not at the center, not in the traditional seats of authority, then we begin to see something of the exercise of power from the margins, from below. When we are given the privilege to see social meaning produced by those in less lofty positions in society, how those people shaped their world, their environment, their social structure, then we have been given a chance to gain important insight into the larger workings of a given culture and society. Even more, if we find that the meaning generated from those marginally produced lists has later made its way to, and become adopted by the center, then we can begin to write history in a way that not only documents those who lived at the margins, but rather how everyone in a given society contributed to its makeup. This book avails itself of the privilege of such lists. | |||

|

Tracing category production historiographically for India presents a difficult task. Histories of India continue to assess group (list) formation there in terms of a limited and inadequate set of primary scenarios: nation, religion (communalism), caste, and class. This is so despite the fact that the most pressing issues of Indian society and politics in the modern era have dealt with the resolution of problems relating to the realization of goals of countless other articulations of identity–from the village to the region to the state to language to gender to access to technological development and so on and so on. | |||

|

Historians have been remiss in addressing this wider range of projects. By failing to do so, histories remain captives of the inherent sets of meanings and ideologies that accompany the basic and insufficient categories that are used to designate the ways in which people and society constituted themselves in India. Instead of venturing beyond these narrow parameters, some scholars ask if it is even possible to write history in a way that exposes itself to its own investment in the culture that created it. They wonder if it will always be, as Dipesh Chakrabarty has postulated, that this "is impossible within the knowledge protocols of academic history, for the globality of academia is not independent of the globality that the European modern has created." 5 | |||

|

Yet adopting this stance has an even more problematic implication–the possibility of not being able to speak on Indian history at all, let alone speak about the history of identity formation. 6 | 5 | ||

|

Yet one way to detach the links between the convenient categories and labels that scholars tend to use as a product of any given set of cultural entailments and our ability to problematize an issue in the first place is to reverse the order of the theoretical guidelines for using categories. A means by which to begin to overcome this problem is to see terms, categories (of identity), as they were understood by the people who made up the constituent parts of those groupings, whether those terms came from local language, tribal, játi category assertion, or other bases–a major goal of this work. Identity as a concept has been and continues to be framed in the same narrowly conceived terms because existing academic labels have become comfortable for scholars, and not necessarily because they are the labels that historical subjects themselves produced. Unraveling this twisted application of categories will require an approach that begins not only with a reflexivity on the parts of scholars, but also by taking into account the ways in which Indians today and historically articulated their own concerns about identity: how they made lists. | |||

|

This work is about articulations of culture. It assumes that articulations of culture are powerful, that they both arise out of historically and politically contingent understandings of that culture, and that they endure as long as those contingent understandings retain or can be instilled with meaning. In particular, this work documents how various descriptions of particular groups and peoples, by those groups and peoples themselves, changed over the course of the nineteenth century in Telugu-speaking India into very specific formulations of identity. One phenomenon in particular is addressed here. It relates to the ways in which people who spoke Telugu dealt with the coming of certain technologies for expression. Indians used these devices to assert historically contingent categories, only a few of which I document here, categories that transcended "traditional" groupings, categories that were products of the needs and imaginations of local groups, categories that emerged at the periphery and were not imposed from above. The convenient labels of caste, class, nationalism, and so forth may have come to be understood by Indians. These, however, did not negate local identities that were in place precisely due to the immediacy of the power of the moments of their creation. Local identities rest on understandings of the historical solidarities that spawned them. The re-referencing of solidarities over the course of time (here, the nineteenth century) hardened and secured the meanings of the categories they forged. | |||

|

I will examine the mechanics of this politics of culture, transformations from articulations of self into internalized identity, among four types of nineteenth-century actors: village boundary disputants, members of the Velama játi, weavers, and petitioners in general. During the first part of the period under inspection, members of all of these groups participated in or experienced some act of solidarity in the process of representing themselves. Years of re-expressing these historically determined solidarities to ever-expanding audiences produced discourses about the essences of those groups. This language of solidarity, in turn, permitted those localized identities to take hold–to become political articulations of the self. Although we will see only documentation found from southeastern India, it is clear that it was the experience of the creation of these very local epistemologies of group identity that later made it possible for individuals to understand and take part in larger India-wide discourses such as those surrounding nationalism, Hinduism, and even tradition. | |||

|

Underlying this nineteenth-century process was a growth in the importance of relationships between Indians and technological and colonial apparatuses. That is, the printing press and British bureaucracies proved to be productive tools for Telugu speakers. In fact, evidence will show that the process was quite different from historian Ranajit Guha's notion that the British learned to adjust to upheaval from below. He suggests, "The formative layers of the developing state were ruptured again and again by these seismic upheavals until it was to learn to adjust to its unfamiliar site by trial and error and consolidate itself by the increasing sophistication of legislative, administrative and cultural controls." 7 | |||

|

Indians were more than merely capable of upheaval in their desire to solve the tensions of dominance and subalternity. Instead, they used available mechanisms to solidify historical alliances and found ways to empower themselves both in relation to the British and to dominant Indian groups. The fact that these mechanisms were newly available to most Indians in the nineteenth century makes that period a particularly fruitful time for groups to be able to formulate what I suggest were new discourses on the self. These were epistemologies that took on contemporary political imperatives, and became the identities that individual members of groups internalized and articulated by the end of the century. | 10 | ||

|

I hope to demonstrate an important trend not marked in recent works that address orientalism and the historiography of India. As opportunities for expression grew and print media outlets increased, societies (and this was most likely the case in Europe as well) developed discourses on themselves, and, in effect, essentialized themselves. The process in this case is similar to the imagined communities that Benedict Anderson posits. 8 But his focus in that work on nationalism ignores the role of smaller community development. Until a body of people developed different ways to articulate who they were at the local level to those outside, through the use of new means for expression, until they worked out a discourse on the self, they did not easily link themselves to larger discursive (imagined) units, even with the appearance of such apparatuses as Anderson's print capitalism. | |||

|

The point to be seen here is that it was not that these identities were unimportant before the coming of colonialism; it was that they did not exist in their contemporary, particular articulable ways. The nineteenth century brought with it the forums for expression necessary to allow a cultivation at all levels of these expressions of identities, the cultivation of the ability to categorize the self contextually for others in the space of these media, and thereby to participate in the politics of the self across huge boundaries. By noting this, we leave ourselves open to register the voices that are and were cognizant of the misapplication of the terms that were the conditions of coloniality in the first place. The job of the historian seeking to go beyond the well defined limits of existing Indian historiography is not to uncover "lost" or "unheard of" histories, but to make clearer for other historians and readers of histories what lies beyond and between the ways Indians have been portrayed to this point. By this I intend Bakhtin's insight into identity: "Man is never coincident with himself. The equation of identity A = A is inapplicable to him. In Dostoevsky's artistic thought, the genuine life of the personality is played out in the point of non-intersection of man with himself, at the point of his departure beyond the limits of all that he is in terms of material being which can be spied out, defined and predetermined without his will, 'at second hand' [zaochno]. The genuine life of the personality can be penetrated only dialogically, and then only when it mutually and voluntarily opens itself." 9 | |||

|

The search for the expression of identity of necessity requires problematizing subjectivity. It requires that we look at the record in a way that does not reinscribe the easily available categories that "others" were in a position to give to groups and individuals–groups and individuals who otherwise might not have been as they were portrayed. | |||

|

When it comes time to critique the contemporary historiography of India, a common lament of scholars is that this or that work would have been so much better if it had only included Indian-language sources or if it had only documented what Indians themselves had to say, apart from the colonial record as collected in the archives. Nita Kumar puts forward that question squarely. "Why, I insist on keeping on asking, given my own predilections in history-writing, is there such a dearth of histories of modern India with the people, especially ordinary people as subject?" 10 To their credit, some scholars have responded to these critiques with histories that include, to varying degrees, Indian voices. Those responses have been, generally speaking, along two lines of thought. The first has been the incorporation into the historiography of Indian elites who had access to technologies of power historically and therefore were in a position to make their ideas available to their posterity and to historians. The second has taken a different road, its goal being to view Indians who were specifically marginalized by colonialism and the elites of the first approach. Included in this second approach have been Guha's insurrectionary peasants, for instance. Importantly, though, these two major directions of thought, despite their apparent dissimilar destinations, intersect at a critical juncture. Both of them make the "Colonial Encounter" (or even the myth of the importance of that encounter) the primary object of their historiographical problematic. Thus the groups of historians who look to Indians as a means to question prevailing attitudes toward colonialism actually include the strikingly different so-called Cambridge school and the people who participate in the Subaltern Studies project. That these are both essentially collections of writers who take as their ideological starting points the problems associated with the colonial encounter may, in fact, be the only thing that links them. | |||

|

Kumar's call for histories to take into account the stories of "ordinary people," however, remains for the most part unanswered. Furthermore, the solution, if there is one, continues to be extremely elusive, especially because the objects of Kumar's critiques (those who exclude ordinary people) are the very historians who are themselves also calling for such a move among scholars. Gyanendra Pandey, himself a participant in the Subaltern Studies project but nevertheless one of the scholars to evoke Kumar's call, for instance, in putting forth his criticism of the Cambridge school has doubts about the possibility of contemporary histories ever going beyond the elite to account for historical change in India. "Most historians betray a deep-rooted faith in the primacy of the elite in determining the character of all political articulation and the course of all political change." 11 Partha Chatterjee also recognizes the special status of what has become perhaps the most privileged of subalterns for Subaltern Studies, the Bengali middle class, who happened to be both in positions of subordination and dominance at the same time. 12 This quandary, which includes the continuing trend to locate the "subaltern" from within groups of elites, becomes more problematic when we consider that even historians who strive to incorporate non-elite Indians in their accounts of events and of change in India, still insist on writing that history in terms of accenting what was done to counter colonialism. They thereby hope to write against the hegemony of the colonial encounter, and the various hegemonizing discourses that arose from that experience, namely, nationalism. But though they may write about peasants, for instance, these writers too participate in a nexus of coloniality by creating a history that is little more than one of alterity–the historiography of resistance. 13 Moreover, this historiography has the potential to generate its own set of problems. Ultimately a significant difficulty in the history of resistance is the staleness of categories that it envisions. That history requires a "true" peasant or a "true" subaltern who may then counter what he or she sees as a powerful center. 14 These histories look at the conflicts ("elementary aspects of revolt") instead of looking at those persons who are in conflict and their subjectivity. | 15 | ||

|

Amid this cacophony of voices attempting to find a place in the academy for histories of those people and ideas ignored by the official record, there has been amazingly little success. Many scholars have felt the work done incorporating elite Indians into the historiography to be sufficient. This has been, as Pandey, for one, points out, one fulfilled goal of the Cambridge school. Underlying this general atmosphere, and what is becoming a growing source of tension among historians, is the question of whether Indians, especially ordinary Indians, really matter in the first place. A number of scholars have followed Guha's lead and have tried to show that the non-elite Indian (here, the peasant) can foment revolt and can have an ideology based on the consciousness of insurgency. This politicizes peasant revolt, to be sure, but it relies on the appearance of the peasant in the record at the moment of his opposition to the colonizer. "Insurgency affirmed its political character precisely by its negative and inversive procedure." 15 Acknowledging such an appearance does nothing to ease the problem of whether the peasant matters in the first place, or in the long term, beyond the moment of the insurrection. Guha's approach unreservedly makes economic structures the bases for the relationships we see and the bases for the events that occur, even if they take on political characteristics in the process of being carried out. None of it takes into account, however, the ongoing changes in the makeup of society at all times and at all levels. This approach may have allowed us to eventuate Indians, offer them subjectivity at those moments when their voices make it to the records, but it does not allow us to attempt to give the historical subject some kind of wide-ranging subjectivity over time. | |||

|

The more recent exchange between Rosalind O'Hanlon and David Washbrook on one hand and Gyan Prakash on the other dances around this very problem, and is a debate that seems to permeate current critiques of Indian historiography. O'Hanlon and Washbrook insist on reasserting Marxist ideas of categories that seem long out of date in describing groups in India. They claim in defense of their position that the postmodernist and Prakash's "post-Orientalist" approaches deny a chance for the "true underclasses of the world" to represent themselves "as classes." Instead those underclasses only receive a particular type of attention that is generated by the middle-class attitudes of the scholars who have made popular this historiography. 16 This lashing-out was in response to Prakash, who had suggested that "post-Orientalist scholarship" would begin with ideas relating to "'politics of difference'–racial, class, gender, ethnic, national, and so forth," which "posits that we can proliferate histories, cultures, and identities arrested by previous essentializations" but does not seek with those ideas "the erection of new foundations in history, culture and knowledge." 17 According to O'Hanlon and Washbrook, Prakash's is an approach that avoids the application of meaningful categories. But Prakash had made this proposal to further a more complex objective for the case of India. He would "unlock history from its 'closures'" through "engaging the relations of domination." This way sees historical writing as itself being the political practice that makes texts "contesting acts." 18 Prakash at least identifies a politics in the writing of history and argues that we must account for this in our narratives of historical events. | |||

|

Given this state of affairs (elites as the only makers of events, peasants as subjects only during insurrections, or the debate as to whether the critical aspects of events lie in the past or with the writing of the history), and here I posit parallels with French historiography of the French Revolution, we are faced with the challenge of bringing a type of Tocquevillian insight to our interpretation of events as a balance to the growing prominence of the dialectic between Marxist and post-modern accounts of history. 19 What is needed is recognition of the wider plane of the historical event. Somewhere at the conjunction of explaining change over time and the ways in which we give historical subjects subjectivity lies an answer of sorts to these issues. To begin with, we must ask a rather fundamental question. How is it that we explain historical changes at all levels in society that occurred in those periods of time between and beyond revolutions, revolts, and insurrections? It is by taking this very question into account, a question that marginalizes the "traditional" idea of an historical event, that we begin to see how non-elites, everyday people, participated in and instigated changes in society, not over the span of an insurrection, but over the course of generations. Because these people did not produce the records that are for the most part available, we must devise other means of observing their places in the formulation of changes, and that means looking around and beyond events as they have been portrayed to this point. 20 Though I will return to these formidable arguments of Indian historiography toward the end of this introduction, at this point I turn to one example of a different kind of approach to sources that may help explain how to reevaluate the meanings of events. By observing discursive means of knowledge production, and the particular cases of category creation and affirmation, I hope to offer some preliminary answers as to how to incorporate "common" people into the wider history of India in general, and the history of nineteenth century India in particular. | |||

|

This work begins by presupposing that categories are tricky things. It may be useful, then, to observe that historians recognize that category management, for instance, was not exclusively under the control of those most dominant groups, and yet how difficult such elusive control is to document. In perhaps some of the most strongly illustrated examples of this contest for control over cultural categories, it has been postulated by historians such as Lata Mani and Partha Chatterjee that the nineteenth century was a time when the British and then Indian elites each, in turn, used women as the modes for contesting dominance in politics and society. 21 For the British, women were the markers of Indian depravity, and thus laws against satí, promoting the possibility of a widow's remarriage, and prohibiting child marriage became central to their calls for social reform in India. For male Indian elites, so the argument continues, women became markers of culture and ultimately the tools to use in its preservation. This prompted calls for new kinds of domesticity for women that reinforced a neo-classical idyll. Chatterjee, for instance, writes of how family life would have to work in order to serve the cause of the nation in its push against the colonizers. Toward this end, he writes, "the crucial requirement was to retain the inner spirituality of indigenous social life. The home was the principal site for expressing the spiritual quality of the national culture, and women must take the main responsibility for protecting and nurturing this quality. No matter what the changes in the external conditions of life for women, they must not lose their essentially spiritual (that is, feminine) virtues; they must not, in other words, become essentially Westernized. 22 | |||

|

But noting that both the British (dominant) and Indian males (slightly less dominant?) battled to make women (far less dominant?) markers of culture in the deployments of certain discourses of control does not speak to the exertions by women themselves, and by the far greater sections of Indian society in general who worked for the actualization of their own power, both in defiance of colonial controls and as means of continuing to play a part on their own terms in the ever-changing spheres of politics in the nineteenth century. This is to say that with the identification of such processes engaged in by the most dominant sectors of society, we still have no clue as to the set of circumstances by which nondominant groups participated in the production of new discourses. As Uma Chakravarti asks, "Whatever happened to the Vedic Dasi?" 23 | 20 | ||

|

My contention has been that this realm of argument and questioning (examining battles between the British and Indian males) is indeed fruitful. But I also contend that historians must now attempt to answer the questions they have only recently begun to raise, questions that arise at the margins of the existing debates. There are ways to show the productive ends achieved by nondominant groups, even with the imperfect predominance of sources left to us by elites. This study seeks to perform such a task. By way of brief example, I offer here a case from the body of traditionally taught Telugu literature. The Sumati Satakam represents, for the purposes of seeing the impact of category creation and protection of meanings surrounding categories, a paradigmatic attempt at the reinscription of structure from above. It is a collection of short verse epigrams produced by Bráhmans with an intention of voicing ideals about society in Telugu-speaking South India. It is one of the first texts that students learned at home and from pundits. 24 Its sentiments, however, did not fully translate into contemporary India and state-controlled educational norms. So today it is selectively doled out to students in Andhra. Its full text nevertheless reveals an important trend that briefly parallels the thesis of this work. | |||

|

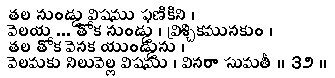

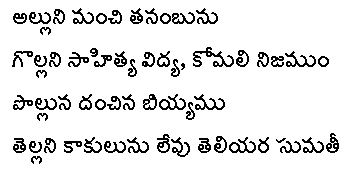

Long before a postcolonial, centralized Indian bureaucratic state arrogated to itself controls over the allowable uses of specific labels referring to groups in society, the Sumati Satakam and those who recited it changed the ways they depicted various sectors of that society. A number of the verses of the Satakam are not used today because they stereotype and denigrate a variety of Telugu játi communities. 25 But the changes in a few particular verses, prior to the relatively recent center-imposed censoring, indicate the power of category and identity formation, and the ways in which epistemologies of játi in society were subject to changes introduced from below. The following verse, itself a list, is one example.

| |||

|

This is the verse as it has been printed in the late twentieth century, amid what has become a standard ordering of the verses, and fairly consistent versions of each. But examination of a number of palm-leaf versions reveals that earlier versions of this particular verse used | |||

|

Of course, one counterpoint to this interpretation has been that  ("Golla") is still in the verse. Bráhmans and those who continue to recite this verse explain that "Golla" no longer refers to the group that may have at one time lived as shepherds, but instead means someone who is a dullard–"golla" with a lowercase "g." In fact, the use of that word in this verse is now being contested in contemporary society, to the extent that the verse cannot be freely cited. The removal of "Kómati" early on (in the version cited here, and certainly by the beginning of the twentieth century) shows that meanings applied to terms referring to groups were becoming closed. This reflected the fact that labeling for communities had become a source of empowerment for those groups who sought to be referred to in particular ways, including those instances of the use of játi names. That there were political and power valences to the terms meant that those terms would no longer be open for use as disparaging labels in general. This is exactly the reason for the importance of categories that I will try to show throughout this work. It is also the reason that categories, and group identity in particular, are so important in our being able to see the flow of power from all sectors in society, while it is not usually evident in overt forms such as the records and other printed texts. ("Golla") is still in the verse. Bráhmans and those who continue to recite this verse explain that "Golla" no longer refers to the group that may have at one time lived as shepherds, but instead means someone who is a dullard–"golla" with a lowercase "g." In fact, the use of that word in this verse is now being contested in contemporary society, to the extent that the verse cannot be freely cited. The removal of "Kómati" early on (in the version cited here, and certainly by the beginning of the twentieth century) shows that meanings applied to terms referring to groups were becoming closed. This reflected the fact that labeling for communities had become a source of empowerment for those groups who sought to be referred to in particular ways, including those instances of the use of játi names. That there were political and power valences to the terms meant that those terms would no longer be open for use as disparaging labels in general. This is exactly the reason for the importance of categories that I will try to show throughout this work. It is also the reason that categories, and group identity in particular, are so important in our being able to see the flow of power from all sectors in society, while it is not usually evident in overt forms such as the records and other printed texts. | |||

|

In one more note about this verse, here it is significant that "woman" can be substituted for a játi group name. This is consistent with Chatterjee and Mani (women became markers for control by men over the cultural domain), but mostly it reveals the general intent and structure of this verse genre. The Sumati Satakam is a means of reinscribing control over society in general. As a text of this sort it is one item in the larger set of discursive media available to Bráhmans. It is a normative text. And it performs its normativizing function through its existence as a satakam (a "traditional" literary form), and by locating–reifying the categories relating to–those whom Bráhman males, and other dominant groups who might recite such a work, would choose to contain. 29 The changes in the text, including that of "woman" for Kómati or "bad man" for Velama, very likely represent the assertion of the power of the articulation of categories–játis–that made certain terms no longer available for use in such a set of signifying verses. Alternatively, Gollas as a group had not yet reached the point of being able to assert játi in the same way. So the printed twentieth-century versions of the Sumati Satakam represent intermediate steps in this particular reflection of changing epistemologies.

| 25 | ||

|

The Sumati Satakam, then, provides one example of a contested epistemology. And in the same way that it reminds us of the debates surrounding the subjectivity and power of marginalized historical subjects and the associated need to problematize the notion of historical events in general, it is the type of example that forces us to recognize our need to engage in the existing heated debates centering on the discourses of identity in the nineteenth century. Thus, before arriving at a discussion of those discourses, we must first consider this debate. The frame of writing histories of India is today so inextricably connected with ideas of coloniality/noncoloniality, Orientalism (Western hegemonic discourses), theories of the "Other," and the like, that to refrain from locating one's work within that nexus is to participate in what can now only be termed a naive attempt at objectivity. This type of "objective" historiography had its day and its representatives. And it is interesting that its proponents now voice a type of anger over discussions that imply that the very weakness of that historiography was its own belief in the possibility of objectivity. 30 Histories of India now tend to find themselves inevitably locating their sources, their own authorship, and their ideologies in relation to the politics of the discourses of postmodernity. This stems from the idea that if historians choose to be careful about these relationships, then they must take seriously their engagement with the sources. Engaging these politics begins even before the act of authoring a work. It begins at the point of identification of the relationship of the author with his or her subject. At that point–the connection between author and subject–a new set of meanings comes to be produced. And that process includes Guha's now somewhat widely accepted idea of dominance versus hegemony. He points out, on the very nature of the historiography, that "the knowledge systems that make up any dominant culture are all contained within the dominant consciousness and have therefore the latter's deficiencies built into their optics." 31 The politics of this connection, as I pointed out earlier, are such that even if they happen to be unarticulated, even if we can identify the nature of the optics without being actively political ourselves (in some sort of nonreflexive way), the valences of the relationship emerge, despite our intentions, through the interpretation of the subject, and even through the very selection of that subject. The subject itself may even emerge in a new form as a fresh product of the selection process. But in every case what results is a set of newly conceived of ideas regarding material relating to a body of people and our understandings of those people, people who existed before and apart from their incorporation into a work of history. | |||

|

An essential task, therefore, for all histories today is to take account of that need for reflexivity and the relationships to the politics of "creating" others (being aware of one's own optics). This by now is a well-worn process of scholarly introspection, and one that is perhaps nowhere more thoroughly engaged than in anthropological field studies. I mention anthropology here for an important reason. The concern for the politics of engagement in anthropology must concern historians also. It has been convenient for historians to believe that "dead" sources produce factual material that can to some degree be unproblematically incorporated into historical writing. As recently as 1992 O'Hanlon and Washbrook wrote, "the past, including its historical subjects, comes to the historian through fragmentary and fractured empirical sources, which possess no inherent themes and express no unequivocal voices. In and of themselves, these sources and voices are just noise: 'Other' histories uncovered do not speak for themselves any more than the 'facts' of history do. To state the obvious, the historian must undertake the prior, and in part subjective, tasks that only the historians can do: to turn the noise into coherent voices through which the past may give the present intelligible answers." 32 | |||

|

This approach does not ring true with large numbers of contemporary scholars. It prompted, for instance, Gyan Prakash's note that "this staging of interpretation as the first encounter between the all-powerful interpreter and the lifeless evidence is blind to the history of its own enactment." 33 Anthropology's living sources can be even more problematic. But the aspect of the larger interpretation blind faced by anthropologists that need necessarily concern historians is the degree to which all parties involved in the production of a text are altered, and themselves alter meanings, as a result of the interactions that take place during that production. Michael Fischer takes this set of producers of meanings as far as the readers of texts, and makes an observation about autobiography that might apply to any number of genres: "The characteristic of contemporary writing of encouraging participation of the reader in the production of meaning–often drawing on parodic imitation of rationalistic convention, or using fragments or incompleteness to force the reader to make the connections–is not merely descriptive of how ethnicity is experienced, but more importantly is an ethical device attempting to activate in the reader a desire for communitas with others, while preserving rather than effacing differences." 34 | |||

|

This suggestion has a number of implications, in addition to what it says about the production of texts in general. One important upshot for anthropology is that the subjects of field studies, in the process of taking part in the writing of the work, do make a difference in the makeup of the anthropologist's society through the interplay in which readers engage. Those subjects of the text also make the experience of encounter a part of their contributions to the ongoing changes in their own societies and cultures. But this also indicates that historical subjects, as a result of their being selected by historians, participate in changes to our contemporary society. And for the sum of these particular reasons it is clear that the reflexivity on the part of the writer is absolutely critical, because the text produces new meanings, as does its reading later. But the anthropological case also suggests that historians must be aware of the historical process whereby encounters such as those in field studies have been ongoing throughout time. Thus changes in meaning have been taking place in this particular fashion (the encounter) throughout history. 35 And these changes are not always reflected in the record due to the one-sided nature of the production of such texts. The acceptance of such reasoning, furthermore, justifies investigations of even the most "insignificant" historical subject who of necessity participated in and initiated changes in his or her own society. | |||

|

The way to observe changes in epistemologies of culture historically, therefore, because the record and its readers themselves are biased (by definition, perhaps), is through the history of the changes of meanings for categories themselves, the history of the production of categories. That is, the categories that are used in the records are not placed there without reference to some articulation by the signified. They cannot be produced solely by those with access to the production of the records. By tracing changes in categories we can observe the production "from below" of new epistemologies about society and culture. An unlikely, but poignant, voice offers insight into this process. Norbert Elias uses one of the most profound historical moments of Western society to identify a change in the self-perceptions that people at all strata of society must have gone through, the case of the abandonment of the geocentric world-picture: "It is obvious that this changed conception of the figurations of the stars would not have been possible had not the prevailing image of man been seriously shaken on its own account, had not people become capable of perceiving themselves in a different light than before." 36 | 30 | ||

|

What the nineteenth-century record may give us ultimately (through its ability to reflect perceptions) is two things: a recording of the changes in the ways people categorized themselves, and the history of how those people were categorized by others in turn. These changing sets of categories, this process of identity formation, as seen in the records, through careful scrutiny, can be one critical way of observing knowledge production within a society whose written history is dominated by the colonial voice. There is an additional feature to investigation of this nature. Because changes in categories can reveal the extent of changes in relationships between groups, we also have a chance to observe the changes in the relationship between colonizers and colonized. | |||

|

Until recently the question might have arisen as to why categories present a legitimate focus of historical investigation in the first instance. Why do they give us any particular insight into the ways changes occurred historically? This question is a corollary to why ordinary people are relevant historically. Categories are, in fact, important not only because they provide the opportunity for us to see how changes occurred in society historically, but also because by the nineteenth century they became the main bases for self-empowerment for those without access to juridical power and all of its capillary institutions. Categories are the tools of subjugated knowledges. Beginning in the nineteenth century people came to see categories as sources of strength against an increasingly bureaucratic colonial state (in Europe, a centralized bureaucratic state) bent on attempting itself to exercise the power of creating meanings for and using labels in special ways. The census, anthropological work, and bureaucratic categorizations were among these projects. But categories, it turns out, were not controllable in the ways that governments and their bureaucracies had hoped. Categories and labels proved to be the devices Indians found available to implement ideas about themselves when interacting with British officials, and when placing those ideas into the record. Thus, though I will expand on categories, it is significant that the history of identity formation in India is a way to see how changes in society overall were instigated by all its facets, and not just those who were positioned at the top. For example, it was not that the census made identity important. It was that Indians saw in the census the opportunity to express identity (perhaps in a new way) as they had been wont to do in other times with other bureaucratic institutions. They saw the empowerment attached to participating in such. As Michel Foucault noted, there is a type of pleasure that accompanies being asked to talk about the self, having attention focused on the self in an interrogative situation. 37 | |||

|

Categories serve as the means by which individuals at the margin are able to access forms of juridical power. To the extent that the modern state functions through its bureaucratic agencies, individuals are forced to articulate categories to that system in order both to be recognized and to be able to gain benefits from it. There exists an obvious upshot connected with this phenomenon. Being able to articulate categories to a bureaucracy can also be a means to exercise power against it. Categories are the basis for the state's ability to organize its citizens in ways that it can control them. If the state can tap into an existing label that citizens agree to, it can then work within the bounds of that category's definition to exercise various powers over the people signified by that category. The ability of a people to oppose this kind of control, or even to shape the control themselves toward some productive end also lies along the same lines that leads the state to be able to succeed as it has done. When groups are able to insist on a particular label, or assert a particular meaning for an existing category, either in an open space, or in a contested venue, then they are able to take on the state on its own terms. Categories, then, are the means by which groups can work within the parameters of an existing state organized framework, but are also the sites for the exercise of subjugated knowledge that seeks to realign the confines of an existing order. Thus groups that have been able to stave off encroaching state interdictions have been able to do so mainly by virtue of a command over the categories that they use for themselves and that they force the state to use in reference to them. State attempts at enclosing categories work to solidify its exertion of juridical power, but eventually fail to encase groups fully. | |||

|

Historically, the process of working out categories, and therefore the process of setting up the relationships that various groups have with the juridical structures of the state, has been complex. Scholars have tried to trace it in various ways in Europe. But little has been attempted in India. The reason for this, it seems to me, has been the supposed power acceded to the nexus of controls of the colonial state by historians in their depictions of the relationships between Indians and that state. On the one hand the colonial experience has been viewed as a premodern phenomenon, so not open to such critiques. That premodern designation placed Indians within the context of the world of mercantile trade, and thereby denied them positions as legitimate sources for an investigation into the exchange, the give and take of dialogue, between rulers and subjects, or Western traders and Indian producers. All the historiography on weavers, for instance, bears this out. As I plan to show later, weavers have been made simple objects of economic forces in the existing historiographical looks at trading relationships of the pre-nineteenth century (mercantile) world. On the other hand, later colonialism in South Asia has been viewed as a completely stultifying experience, one that led to the totality of western hegemonic rule over a huge area, a rule that encapsulated juridical forms of power, as well as a complete range of discursive means of control through the power/knowledge relationships of Orientalism. Gauri Viswanathan, taking this idea to heart, has gone as far as to claim that "the English literary text, functioning as a surrogate Englishman in his highest and most perfect state, becomes a mask for economic exploitation ... successfully camouflaging the material activities of the colonizer." 38 This acceptance of the supposed totality of colonialism has discouraged historians from looking at the intense negotiations that went on under what was actually a very porous set of administrative structures. 39 | |||

|

The extent to which the East India Company and, later, the British government were actually partners with Indians in the process of working out systems of rule has scarcely been examined. Even less frequently considered has been the idea that the very structures of rule were predicated on the ways in which categories were worked out over long periods of time both for Indians themselves and in the course of understanding the nature of their relationships with government. That categories and meanings were never not important is a naive-sounding but nevertheless critical reminder of how systems of society have always functioned. It is important to remember that the nineteenth century was a time during which categories became important in new and special ways. The nineteenth century saw a serious attempt made to overlay a thorough bureaucratic system onto Indian society, and because the very basis for the success of such bureaucracies has been their ability to exercise control over the meanings that categories convey, the struggle to arrive at agreed-on meanings for those categories in nineteenth-century India took on new implications. The increased availability of travel, the introduction of printing at a broad level, new media for expression within the bureaucracy, and the very basic process of deciding how to rule the populace (through laws ranging from land tenure to social reform to the workings of the census) all contributed to the needs people felt to insist on particular meanings and understandings for categories that had come into use historically, years and even ages earlier. Identity, then, is the gloss I give to the ways people came to categorize themselves. As the set of categories that applies to the self, identity has that critical reflexive aspect. But in the age that saw the rise of a new politics of culture that brought with it a wider incorporation of peoples into systems of juridical power, identity took on an importance for individuals and groups that was not there before. | 35 | ||

|

The new identities that we witness emerging in the early nineteenth century were historically contingent as well as articulable. Before the nation emerged as a distinct discourse, those groups who would later be Partha Chatterjee's "fragments" were already participating and producing discourses on themselves, framing their own identities. | |||

|

In chapter 2 I examine documents dealing with the settlement of village boundary disputes. In these there exists the possibility of many people with distinctly different social entailments to come together for the purposes of articulating a village identity. The disputes here took place in the very early years of the nineteenth century. What this produced was a series of groups of people from all backgrounds who early on become savvy in the politics of the self, and imaginative in being able to create new categories on their own, or attach new meanings to given categories through the medium of a bureaucratic forum, in this case how they worked with local officials, and the petitions they submitted to engage in that dialogue with officials. | |||

|

Chapter 3 looks at what became the most important medium with which Telugu speakers chose to articulate concerns to government officials. The petition was not only a bureaucratic institution to formalize expressions of dissent, but also a popular way to talk about one self and one's concerns and to bring those concerns to the attention of government officials. In two main ways the petition shows the indicative changes in articulations of the self. First, over time, petitioners became more familiar with the petition as genre, and expressed concerns more freely within it. This proved to make the petition a space exactly suited to frame references to and definitions of the self and groups. Second, from the later eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries a trend developed whereby petitioners more carefully used category terms. As categories came to be more or less contested, the language of culture and identity changed accordingly, as is visible in petitions. It was the general presence of the petition and its two main historical features that provided for the forging of identity through the articulation and rearticulation of the self. | |||

|

In an examination of the telling and retelling of a story about the siege of Bobbili in 1757 (chapter 4), we can see that a group of people emerge, the Velamas, whose new "caste" identity is intrinsically tied to this relatively recent event. Caste as it is articulated by the tellers of the story in the twentieth century is drastically different from the játi grouping we see in the earlier tellings. It is this later identity–by now caste–that provides for Velamas an understanding of the politics of the articulation of the self and the politics of being as a means to assert and maintain a group label. This is a category that grows alongside nationalism, but one that can exist apart from it and not be subsumed within it. | |||

|

Finally, in chapter 5, a reevaluation of the label "weaver" in the nineteenth century indicates that those who wove, through the adoption of this category in a distinct manner from that of purely colonial export functionary, fashioned themselves into a self-acknowledged group. With that state of understanding in hand, they were able to hearken to their protests of the earlier part of the century when establishing their identities as weavers, to the exclusion of so called "traditional weaver caste" categories. This chapter in particular has a likeness to Guha's work in its requirement that we read against the grain of the sources (official records that assume a substantive and opaque "weaver" label early on), but it questions the very nature of the label "weaver" in a way that "peasant" is not problematized for Guha. | 40 | ||

|

In all these cases there existed moments of historical solidarities to which groups might refer to strengthen the calls they made for their identity categories. Over the course of time all of the groups that could do this historical referencing were also able to articulate the bounds of their identities as discursive means for self-empowerment. These categories lay beyond the reach of all-India discourses that were developing at the same time in the nineteenth century. But what the historical process of being able to assert these local identities ultimately provided was a structural means for these groups to tap into larger discourses such as nationalism while at the same time being able to retain and distinguish their own identities and the discursive tools they had developed to articulate those identities. It is then by looking at the process of category production through the experience and retelling of historical solidarities that I am able to posit a model for the individual (not simply as a subaltern) to speak and be heard. By looking at the points of access (through discursive fields) to structures of juridical power, I feel I have been able to, in special ways, avoid a starting point that locks me into the use of categories arrived at through a belief in the hegemony and dominance of Western modes of power deployment–class, caste, nation and their corresponding peasants and subalterns. | |||

|

Notes: Note 1: :The singer of the Bobbili Katha lists some of the groups of people in the army of a raja. Sri M. Somasekhara Sarma, ed., Bobbili Yuddhakatha (Madras, 1956), 10—11.Back. Note 2: From a list of groups making up the constabulary in Madras, as noted in Report on the Administration of the Madras Presidency, 1869—70 (Madras, 1870), appendix II, lxiv.Back. Note 3: A list of petitioners from Mangalagiri who participated in the settlement of a village boundary dispute. Masulipatam District Records, vol. 3074B, fol. 450 (17 January 1799).Back. Note 4: From a list of employees in a zamindar's household. Masulipatam District Records, vol. 3074B, fols. 591—592.Back. Note 5: Dipesh Chakrabarty, "Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History: Who Speaks for 'Indian' Pasts?" Representations 37 (Winter 1992): 23.Back. Note 6: Of course, this predicament does not end with historians. Anthropologist James Clifford has noted that such "questions are sometimes thought to be paralyzing, abstract, dangerously solipsistic–in short, a barrier to the task of writing 'grounded' or 'unified' cultural and historical studies." Clifford, "Introduction: Partial Truths," in James Clifford and George Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley, 1986), 25. But just as Clifford offers an answer for anthropologists by recognizing that for all texts "what counts as 'realist' is now a matter of both theoretical debate and practical experience," there may be a way to speak about India and Indians without necessarily speaking "for" them.Back. Note 7: Ranajit Guha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (Delhi, 1983), 2.Back. Note 8: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London, 1991).Back. Note 9: Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics (Ann Arbor, 1973), 48.Back. Note 10: Nita Kumar, review of The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India by Gyanendra Pandey, Collective Action and Community by Sandria Freitag, and Mirrors of Violence, ed. Veena Das, Indian Economic and Social History Review 29, no. 2 (1992): 229—230.Back. Note 11: Gyanendra Pandey, The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India (Delhi, 1992), 20.Back. Note 12: Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments (Princeton, 1993), 36.Back. Note 13: Here consider the wider set of writings represented by James Scott and his The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (New Haven, 1976) and Ranajit Guha, Elementary Aspects, whose main focus is on aspects of peasant opposition to juridical power and hegemonic discourses, instead of focusing, for instance, on aspects of peasant productions of knowledge.Back. Note 14: Of course, one further danger here is that Guha's fixed categories come perilously close to Louis Dumont's vision of caste. In the first case class categories are subsumed within the economic and social realm, whereas in Dumont's case caste is firmly entrenched within religion. Both sets of categories become unassailable by theory. See Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implications (Chicago, 1980).Back. Note 15: Guha, Elementary Aspects, 9.Back. Note 16: The full text of the quotation is as follows: "What it means is that the true underclasses of the world are only permitted to present themselves as victims of the particularistic kinds of gender, racial, and preponderantly middle-class American scholars and critics, who would speak with or in their own voices. What such underclasses are denied is the ability to present themselves as classes: as victims of the universalistic, systematic and material deprivations of capitalism which clearly separate them off from their subaltern expositors. In sum, the deeply unfortunate result of these radical postmodernist approaches in the minorities debate is thus to reinforce and to give new credence to the well-known hostility of American political culture to any kind of materialist or class analysis." Rosalind O'Hanlon and David Washbrook, "After Orientalism–Culture, Criticism, and Politics in the Third World," Comparative Studies in Society and History 34, no. 1 (Jan. 1992): 166.Back. Note 17: Gyan Prakash, "Writing Post-Orientalist Histories of the Third World: Perspectives from Indian Historiography," Comparative Studies in Society and History 32, no. 2 (Apr. 1990): 406.Back. Note 18: Prakash, "Writing Post-Orientalist Histories," 407.Back. Note 19: Keith Michael Baker writes of the historiography of the French Revolution that "the reorientation that has occurred can be characterized as a shift from Marx to Tocqueville, from a basically social approach to the subject to a basically political one." According to François Furet, what Tocqueville offers "is that situation which allows us to restore to events the extraordinary share of historical initiative that is their very hallmark and at the same time to reinsert the Revolution into the historical continuity out of which it so passionately wished to break." Keith Michael Baker, Inventing the French Revolution (Cambridge, 1990); François Furet, "A Commentary," French Historical Studies 16, no. 4 (Fall 1990): 801. Back. Note 20: In her work on colonialism in Java, and in particular where she looks to memories as alternatives to the colonial archive, Ann Laura Stoler generates an important discussion centering on issues similar to those we see in Indian historiography. See, for instance, her Race and the Education of Desire: Foucault's History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (Duke University Press, 1995). More to the point here, in an article entitled, "Castings for the Colonial: Memory Work in 'New Order' Java," Comparative Studies in Society and History 42, no. 1 (Jan. 2000): 4—48, she and Karen Strassler specifically target Gyan Prakash's "Writing Post-Orientalist Histories," Dipesh Chakrabarty's "Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History," and other recent writings on colonial encounters: A commitment to writing counter-histories of the nation has privileged some memories over others. Because it is often restoration of the collective and archived memory of the making of the postcolonial nation which has been at stake, the critical historian's task is to help remember what the colonial state–and often the nationalist bourgeoisie–once chose to forget. The assumption is that subaltern narratives contain trenchant political critiques of the colonial order and its postcolonial effects. But this commitment may generate analytic frames less useful for understanding memories unadorned with adversaries and heroes, compelling plots or violent struggles. Such focus on event-centered memory may, in fact, block precisely those enduring sentiments and sensibilities that cast a much longer shadow over people's lives and what they choose to remember and tell about them. It might be argued that this is all beside the point: everyone knows that memories are not "stored" truths but constructions of and for the present. Whether applied to the personal or the social, in this "identity" model memory is that through which people interpret their lives and redesign the conditions of possibility that account for what they once were, what they have since become and what they still hope to be. Treating memory as a self-fashioning act of the person or the nation places more emphasis on what remembering does for the present than on what can be known about the past. With their focus on memories of the "everyday," Stoler and Strassler widen the scope for colonial "counter-histories." While what I take from this widened scope may not be the use of contemporary memory, it is its suggestion for the opportunity to retain the use of investigation into certain "event-centered memory" in my sources that stems from events more of the "everyday" variety than of the "insurgency-driven" type that Guha privileges. In this vein I will not call on any given event to serve as the privileged core for the makeup of any one particular identity. In either case, event-based or not, memory will be critical in pointing us to certain characteristics of identity in a way that Stoler and Strassler rightly hearken to Boyarin's argument that "identity and memory are virtually the same concept." (As quoted in Stoler and Strassler, p. 42, n. 27, from Jonathan Boyarin, ed. Remapping Memory: The Politics of TimeSpace [Minneapolis, 1994], 23.)Back. Note 21: See Lata Mani, "Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India," in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid, eds., Recasting Women (New Brunswick, 1990), 88—126; Partha Chatterjee, "The Nationalist Resolution of the Women's Question," in Sangari and Vaid, eds., Recasting Women, 233—253; Chatterjee, "Colonialism, Nationalism, and Colonized Women: The Contest in India," American Ethnologist 16, no. 4 (Nov. 1989): 622—633.Back. Note 22: Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments, 126.Back. Note 23: Chakravarti ends her article by noting, "Vast sections of women did not exist for the nineteenth century nationalists." Uma Chakravarti, "Whatever Happened to the Vedic Dasi? Orientalism, Nationalism, and a Script for the Past," in Sangari and Vaid, eds., Recasting Women, 79.Back. Note 24: One legacy of this tradition of learning is that palm-leaf versions of the Sumati Satakam are some of the most widely available Telugu documents from the nineteenth century extant in manuscript libraries in Madras and Andhra Pradesh today. See collections of palm-leaf manuscripts in the State Government Oriental Manuscript Libraries of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, as well as the manuscript collections at the Adyar Library, Madras, and the library at Venkateswara University, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. Back. Note 25: The use of játi here and throughout is specifically in opposition to "caste" and is done to refocus attention toward játi's Telugu-area role as birth-based groups with Telugu-language names. The nuances in the meaning of játi will be developed throughout this work. Back. Note 26: Sumati Satakam (Madras, 1895), verse 9. The translation is mine.Back. Note 27: For the older versions see, among others, MS Sumati Satakam, ed. Charles Philip Brown (Government Oriental Manuscript Library, Madras, No.D3090, 1832), verse 29, and MS Sumati Satakam, on palm-leaf (Andhra Pradesh Oriental Manuscript Library, Hyderabad, ACC #5641; T13-26), verse 91.Back. Note 28: Today the following verse is printed with khalunaku (bad man) in the place here where "Velama" sits:

From Sumati Satakam, Andhra Pradesh State Oriental Manuscript Library, Hyderabad, Acc. No.: 3404, Call No.: T13-76, verse 32. For the printed version see, for instance, Sumati Satakam (Vijayawada, 2000), verse 54, p. 28.Back. Note 29: "Satakam" means literally "one hundred," but it has also come to mean a collection of one hundred verses. This has extended to the name for any collection of verses in the vicinity of one hundred in number, but is generally understood to be of a specifically arranged nature (in devotion of a god or themselves edifying, for instance). The satakam was a widespread genre of collected verse throughout Telugu-speaking areas in this period. See J. P. L. Gwynn, A Telugu—English Dictionary (Delhi, 1991), 510. V. Narayana Rao discusses the role of the satakam in Telugu literature in the introduction to his translation of the Kalahasti Satakam. See Hank Heifetz and Velceru Narayana Rao, trans., For the Lord of the Animals: The Kalahastisvara Satakamu of Dhurjati (Berkeley, 1987).Back. Note 30: This was visible to some extent in the strident views of O'Hanlon and Washbrook, but is even more evident elsewhere. For example, David Kopf responded to Edward Said's Orientalism with an article entitled "Hermeneutics versus History," Journal of Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (May 1980): 495—506. Kopf, of course, was implying that history as a field was not an appropriate venue for Said's hermeneutics or, for that matter, Said's politics. And ten years after that, Robert Frykenberg's review of Gauri Viswanathan's Masks of Conquest, in American Historical Review 97, no. 1 (Feb. 1992): 272—273, declared that an approach such as hers (that English language teaching in India may not have been as innocent as most might think) "may pass for scholarship or become high fashion in some academic circles. But the discipline and practice of history requires more."Back. Note 31: Ranajit Guha, "Dominance without Hegemony and Its Historiography," in Ranajit Guha, ed., Subaltern Studies VI (Delhi, 1992), 216.Back. Note 32: O'Hanlon and Washbrook, 149.Back. Note 33: Gyan Prakash, "Can the 'Subaltern' Ride? A Reply to O'Hanlon and Washbrook," Comparative Studies in Society and History 34, no. 1 (Jan. 1992): 173.Back. Note 34: Michael Fischer, "Ethnicity and the Post-Modern Arts of Memory," in Clifford and Marcus, 232—233. Fischer here could just as easily be talking about identity as he is about ethnicity.Back. Note 35: See especially Marshall Sahlins, Islands of History (Chicago, 1985) for his discussion surrounding the structure of historical encounters.Back. Note 36: Norbert Elias, The History of Manners: The Civilizing Process, vol. I (New York, 1978), 254.Back. Note 37: See the general argument presented by Michel Foucault in his The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction (New York, 1978), 34.Back. Note 38: Gauri Viswanathan, Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India (New York, 1989), 20.Back. Note 39: An exception to this has been Eugene Irschick, whose approach examines negotiations of this sort in Tamil-speaking areas of South India in his work Dialogue and History. See Eugene Irschick, Dialogue and History: Constructing South India, 1795—1895 (Berkeley, 1994).Back.

| |||

(Kómati, a játi name) instead of

(Kómati, a játi name) instead of  (kómali, "woman"), almost exclusively.

(kómali, "woman"), almost exclusively. ("bad man") for

("bad man") for  (Velama, another játi name), as

(Velama, another játi name), as  ("Learned Sudra") is replaced with

("Learned Sudra") is replaced with  ("ignorant miscreant"). The first phrase is found in

("ignorant miscreant"). The first phrase is found in