Chapter Three

"When Mother Lets Us Sew":

Girls, Sewing, and Femininity

The first line of a sewing textbook from the 1890s reads, "Girls: You have now become old enough to prepare for woman's duties; one of these is the art of sewing, which we will take up as simply as possible. By following the given instructions carefully, you will become able to dress your dolls, assist your mothers in mending, make garments, fancy articles, etc."1 A decade later, a girls' sewing club near Boston made dolls' clothes to raise funds for charity.2 The Colored American Magazine praised sewing classes for African American teens, and Jewish and Italian immigrant girls took sewing classes at a settlement house on the Lower East Side. There was a great deal of variety in both ideology and practice regarding girls' sewing education. Despite economic and social changes, however, girls from all backgrounds were encouraged to sew.

The specific reasons why girls were taught to sew and the settings in which that education took place depended on their social class, ethnicity or race, and geographical location. Girls, teenagers, and adult women of a variety of backgrounds often used sewing skills for different reasons. Most sewed chiefly in the home, but others worked in the garment industry as machine operators and piece workers, while others ran their own dressmaking establishments. But most girls would sew for themselves and their families at some point in their lives. Some educators, sensitive to or prejudiced by differences in race, class, and region, tailored their curricula to particular populations and their supposed futures. As a result, some girls received a very practical education in sewing, whereas others learned more decorative skills that may or may not have been applicable to their daily lives. Some were channeled into vocational training that prepared them for work in industry or domestic service while others learned to run a middle-class household. A close look at how girls were taught to sew can therefore act as a microscope for understanding the cultural meanings of home sewing.

In addition to looking closely at how class, region and race shaped girls' sewing, this chapter will address the relationship between girls' sewing and changing conceptions of gender during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. How, why, and what were girls taught to sew at a time when growing numbers of American women worked outside the home and clothing was increasingly available for sale? Moreover, what could girls actually sew and how did they feel about it? As sewing skills became less crucial to running a household, they gained in symbolic importance as a means of teaching cultural and gender ideology. Sewing embodied a set of values such as discipline, creativity, thrift, and domesticity considered critical for preparing girls for adulthood. How did girls respond? Did they emulate their mothers? Did they resent the emphasis placed on domestic work? Did they enjoy sewing as a creative or social outlet? Altogether, how did girls respond to the cultural as well as the pragmatic dimensions of sewing?

^topLearning at Home

The obvious starting point for sewing education was the home. Most adult women already knew how to sew and they often taught their daughters basic skills. Mary Ellen Coleman Knapp, born in 1904 in St. Louis, was taught to sew by her mother and made doll clothes out of scraps from her mother's sewing projects.3 Jane Dunn, who was born in 1913 and grew up in New Jersey, also learned to sew by making doll clothes at home. Mrs. Dunn recalled making simple dresses by folding over a piece of cloth, cutting a drawstring neck and armholes, and sewing one seam down the side.4 Marion Goodman helped her mother by sewing on buttons and snaps.5 It was much more unusual for a girl to learn to sew from her father. Florence Epstein's mother did not enjoy sewing, so her father, a Jewish immigrant from near Bialystock, taught her to use a treadle Singer machine in the early 1920s. Epstein shared memories of her father patiently pinning her skirt hems while she stood on the dining room table.6

Publishers understood that many girls were taught to sew at home and provided books and dolls for young girls. One appealing book for young girls, Easy Steps in Sewing, For Big and Little Girls, or Mary Frances Among the Thimble People, taught basic hand sewing techniques through a story about a lonely little girl who spent summers with her grandmother. 7 Much to her delight, Mary Frances finds that the tools in her grandmother's sewing basket are alive and teach her to sew for her doll. The book ingeniously contains miniature tissue-paper patterns for each project. In addition to teaching skills and inculcating a desire to sew, the "thimble people" taught lessons about proper attitude: Mary Frances is taught to work diligently, have patience, obey her grandmother, clean up after herself, and express maternal feelings for her doll as she dresses it.

Toy manufacturers also jumped on the sewing bandwagon. Bradley's Tru-Life Paper Dolls encouraged girls to design and make tiny dresses. The box contained three girl dolls, patterns, colored "fashion plates," cardboard "buttons," and paper "cloth" in several designs, including gingham check. The instructions claimed:

[The dolls] provide a new and interesting means of industrial occupation embodied in the most pleasing pastime known to childhood. They teach the child how to make dresses in just the same manner as its own little dresses are made, and assist her to cultivate subconsciously a really educational discrimination in the selection of material, color schemes and styles.…Any child will find delight in producing, as the results of its own efforts, pretty dresses for her paper dolls – dresses made in the style she prefers, cut out to fit perfectly, and which look just like the product of a real dressmaker. The patterns are all miniature reproductions of modern styles, each being a facsimile in every detail of a present-day fashionable design.8

Paper dolls were hardly a new concept – children had been cutting out figures and outfits since paper became cheap enough to be "wasted." Now, however, this toy was considered educational, as a writer for the Delineator noted: "How many mothers, I wonder, realize the possibilities of the paper doll as a factor in home training. Very few, I imagine, and yet scarcely any other plaything can be made to interest through all the years of childhood and early youth." Like the Bradley doll set promoted a decade later, the author believed that paper dolls were a valuable means of teaching children real skills: "Children carried on [sic] in this kind of play cannot help but grow to be competent, artistic housekeepers."9

^topSchools, Race, and Class

Despite such endeavors, some girls did not learn to sew at home. Their mothers may have worked outside the home full time, may not have known how to sew themselves, or may have disliked sewing. Although Helen Schwimmer could sew by hand, her mother feared Helen would break the sewing machine and did not teach her to use it until she was fourteen.10 Other children, such as Alice Owen Caufield and her sister, did not have a mother to teach them. For the Caufields and many other girls, public schools were a main site of sewing education.

Patricia Gordon and Marian Goodman | Read transcriptIn 1891, the Boston primary schools organized an exhibit which included aprons made in classes; the pamphlet describing the exhibit explained that schools taught sewing because, like reading and writing, it was "general preparation for the duties of life."11 Sewing had been taught in the Boston school system since at least 1820. In 1835, the city's school board had resolved that young girls would learn sewing skills at least one hour each school day. In 1854, the board asserted that "no girl could be considered properly educated who could not sew." By the end of the nineteenth century, Boston schools were requiring girls to learn sewing for two hours a week in the fourth, fifth and sixth grades and in some situations, into high school.

The New York City public schools followed a similar pattern. In 1896, an exhibit compared the work of schoolchildren from New York, Philadelphia, Rochester, New Haven, and Baltimore with samples of work from European and Japanese schools. Charles Bulkley Hubble, president of the New York City board of education, declared at the exhibit's opening, "We have reached the point where we deem manual training, inclusive of sewing, as a most important factor in the school curriculum. The needle in the hands of a woman is like the plough in the hands of a man."12 Hubble attributed what he saw as "the present movement in favor of teaching sewing in American public schools" to the group that organized the show, the New York Association of Sewing Schools; that such an organization even existed is evidence of the general attitude regarding children's sewing.13

The African American community also considered sewing education to be useful and necessary. African American women faced few job options, limited resources, and severe prejudice; sewing could offer them work skills and access to domestic respectability.

Historian Stephanie Shaw argues that middle-class African American families often urged their daughters to learn to sew as an acceptable backup to other plans. According to Shaw, "Domestic ability, especially hatmaking, baking, and sewing, prepared these women to earn an income without leaving their homes if they were unable to obtain work in the professions."14 Employment as an independent dressmaker was far much preferable to domestic service. Besides, argues Shaw, even if African American girls did not work outside the home as adults, homemaking skills helped reinforce their efforts on behalf of "racial uplift."

The African American community also considered sewing education to be useful and necessary. African American women faced few job options, limited resources, and severe prejudice; sewing could offer them work skills and access to domestic respectability.

Historian Stephanie Shaw argues that middle-class African American families often urged their daughters to learn to sew as an acceptable backup to other plans. According to Shaw, "Domestic ability, especially hatmaking, baking, and sewing, prepared these women to earn an income without leaving their homes if they were unable to obtain work in the professions."14 Employment as an independent dressmaker was far much preferable to domestic service. Besides, argues Shaw, even if African American girls did not work outside the home as adults, homemaking skills helped reinforce their efforts on behalf of "racial uplift."

In a 1905 article in The Colored American Magazine, Margaret Murray Washington praised practical training and sewing in particular. She discussed African American students in "the secondary and higher schools of the race" – many of whom were enrolled in industrial training courses – and claimed that female graduates were in a position to uplift the race:

If one should take the time to go into the homes of these women, whether single or married he would find a broadening of the family circle, tasty furnishings, order, cleanliness, softer and nicer manners of the younger children, a stricter idea of social duties and obligations in the home.15

In addition to helping women care for their families or to earn money sewing for paying customers, sewing skills were directly translatable into teaching careers, one of the more desirable of the narrow occupational options available to African American women at the time. Washington described one graduate who helped her family by teaching school and working as a dressmaker in the summers. She concluded by arguing that "teachers of the arts of dressmaking, millinery and weaving are in demand, and the time will come when our public schools will need women who can both think and act. These two things were never intended to be separated."16

Vocational training in sewing was offered to working-class girls of all racial and ethnic backgrounds. The thinking was that girls needed to learn to sew in an industrial or domestic service setting as well as in their own households. A journalist for the New York Times offered a third reason for teaching working-class girls to sew – a solid background in sewing would keep them from taking men's jobs:

The accusation that women are invading masculine domain in seeking to earn a living cannot be lightly considered, for it is a patent fact that some of woman's own peculiar provinces are superficially treated, and in some instances quite neglected… Dressmaking should be just as much the part of a liberal education for a girl as manual training is for a boy… if a girl can't mend her dress neatly, she is not fit to take upon herself the care of her own children later in life. In these days of ephemeral fortunes, what young women is sure, though she marry a millionaire, that her circumstances will always allow her to pay for the sewing of a family?17

According to this writer, an education in sewing ensured that working-class girls would be fit to run a household and so would no longer threaten the job prospects of more deserving men.

Sewing instruction could thus reveal ingrained ideas about class and race. Different groups of girls were taught to sew in varying ways was because authorities – school boards, textbook publishers, contest organizers, etc. – felt that African American or working-class Jewish or Native American or rural girls needed to sew for different reasons. Such beliefs were not inherently a sign of racism or prejudice; they often reflected economic and social realities that shaped girls' lives. Many working-class immigrant girls did in fact need to earn a living, and rural girls would likely run a farm household. Still, these assumptions became problematic when they limited girls' options and used past experience and present reality to determine their futures.

I have already argued that many African Americans believed sewing was an important skill for women. As problematic as vocational training may have been, many African Americans sought to provide sewing lessons for their children, but the limited education available to most African Americans was echoed in the access to, and scope of, sewing training. Some children learned in someone else's home – a photograph of a woman surrounded by ten children and adolescents on a porch is captioned "Mrs. Louisa Maben and Her Sewing School."18 This kind of arrangement may have been common, since a survey undertaken in 1923 found that

courses in home making in the public schools for colored children are limited in number. In a few large cities home-economics courses are offered in the high schools, but expense of equipment and maintenance have usually barred it from the elementary schools and have limited its development in high schools.19

One African American institution that encouraged sewing education was the Hampton Institute. Opened in 1868 in Virginia, the Hampton Institute offered vocational and academic training to African Americans and Native Americans. Hampton also ran the Hampton Summer Normal, the first summer school for teachers from African American schools in the South who, according to an article in the Colored American Magazine, came to the program "for inspiration and help in this work of uplifting the race."20 Like many articles in the same publication, the author praised vocational training. She wrote that the teachers recognized that most of their students would work as farmers, and, "always thinking how best to serve those for whom they labor, many rural teachers elected the course in sewing, so that they might introduce it in their schools."21 A posed photograph of a dressmaking class at the Hampton Institute was part of a photography exhibit on the "contemporary life of the American Negro" at the Paris Exposition of 1900.22 The same exhibit included dramatic "before" and "after" images of squalid living conditions changed into tidy homes by virtue of a Hampton education. These posed photographs are problematic in their allegiance to vocational training to the exclusion of other social changes, but they offer a good sample of skills thought to be "uplifting."

One African American institution that encouraged sewing education was the Hampton Institute. Opened in 1868 in Virginia, the Hampton Institute offered vocational and academic training to African Americans and Native Americans. Hampton also ran the Hampton Summer Normal, the first summer school for teachers from African American schools in the South who, according to an article in the Colored American Magazine, came to the program "for inspiration and help in this work of uplifting the race."20 Like many articles in the same publication, the author praised vocational training. She wrote that the teachers recognized that most of their students would work as farmers, and, "always thinking how best to serve those for whom they labor, many rural teachers elected the course in sewing, so that they might introduce it in their schools."21 A posed photograph of a dressmaking class at the Hampton Institute was part of a photography exhibit on the "contemporary life of the American Negro" at the Paris Exposition of 1900.22 The same exhibit included dramatic "before" and "after" images of squalid living conditions changed into tidy homes by virtue of a Hampton education. These posed photographs are problematic in their allegiance to vocational training to the exclusion of other social changes, but they offer a good sample of skills thought to be "uplifting."

At least some African American women who were taught sewing and other household tasks used these skills to earn a living and viewed their training as beneficial. Melnea Cass graduated from a Catholic boarding school for "underprivileged girls" (mostly Native American and African American) in 1914. In addition to a full academic course load, she and her classmates studied domestic science. Cass recalls:

We had time when we did domestic work, when we learned how to keep the house and all that, because mostly colored girls at that time were hired out as domestics. So they taught us that too. So you really could do that, too, if you wanted to wait-the-table, cook. We had cooking classes. And all sorts of things that made you learn how to do things in a house, if you were going out to work in a house. It was very good, because most of us did go out and work in the house; we who couldn't go on to college, you know.23

Cass recognized that she and her classmates would need to earn a living and that the job opportunities available to them were severely limited. Not all African American girls had as broad an education as Cass, however. The idea that sewing was a way to provide uplift for African Americans and therefore a necessary subject in schools could backfire if practical skills took priority over more academic training. Moreover, the decision of white administrators and educators to emphasize practical training over academics reveals their bias toward African American as workers who should work for whites or as people inherently unable to provide for themselves.

Elizabeth Holt, a white home economist, was convinced that African American families needed domestic skills in order to improve their alleged unsavory habits. Instead of acknowledging chronic discrimination and violence as factors affecting African American homes, she wrote that "the original racial instincts of the negroes, and the poverty in which they have lived from the time that the support of the wealthy slave-owners was withdrawn, have caused the home life of the present-day negro to be utterly lacking in system, cleanliness, and comfort."24 Holt, who wrote about the African American public schools in Georgia, claimed that sewing and other housekeeping classes were instrumental in improving living conditions, but she was also concerned about preparing African American children for the workforce, claiming that domestic training "may enable them to render efficient service in the lines of work that they must necessarily follow in this section of the country under present conditions." 25 To someone like Holt, training in sewing, cooking, and laundry would make African American girls better laundresses and domestic servants. This goal is made clear when she explains that graduates of the "industrial program" will receive certificates – and that "the names of those receiving the certificates are kept on record, and so far as possible their future records as house-servants will be inquired into."26 While Holt later concedes that "if on the other hand they do not go into service, we propose to qualify them for keeping better homes of their own," her emphasis is on using vocational training to create workers.

Holt was walking a fine line between condescension and pragmatism. Sewing skills were useful in African American homes, just as they were in white homes. Indeed, given the economic differences, home sewing might have been relatively more helpful to African American women. Besides, as Cass's experience demonstrates, because of the need for African American women to work, many girls found such training helpful in finding a job. The problem was that instead of complementing other schooling, sewing and other vocational training often took precedence over academic training. Holt claims that

this industrial education is not being forced upon the negro. In fact it was first introduced into the white schools, and there the negro leaders in the educational life of the community, seeing the great advantage that it would be to their people, asked that they also might have it. In order to forestall any denial of their request by the Board of Education for financial reasons, they voluntarily offered to reduce the ‘book-learning' of the schools in order to use some of the regular grade teachers in the new Industrial Department.27

At least some African American school administrators went along with the plan, agreeing – at least in the article – with the idea that sewing and related classes were beneficial for students. One principal is quoted as saying:

Since sewing and cooking have been introduced into our school the teachers of the school, together with the friends, both white and colored, have remarked that the pupils are neater and cleaner in their personal appearance and more orderly in their conduct. A number of their employers have testified that they are more helpful to them now than they were before the work was introduced. The children themselves are so interested that they are willing to work before and after the regular school hours.28

In 1912, girls in African American grammar schools in Georgia spent about five hours a week in cooking, four in sewing, and three in laundry. This is more time devoted to such training than other comparable school systems allowed in their schedules. According to the same article, many of these schools only went through the seventh grade. While sewing and housekeeping lessons were surely very handy in the home, opened doors for employment, and offered girls and women means for personal expression, was it worth slighting other subjects? Did African American girls learn sewing at the expense of other skills that could have provided more chances for social and economic mobility?

Native American girls were also offered sewing education, but with a very different agenda. Girls at government-run boarding schools were trained to sew, often with the presumption that they would return to reservations and that their training would help them run a "proper household" and care for others who had not been "Americanized." Government-run boarding schools for Indian children have come under intense criticism. The schools forced children to wear Western clothing and speak English and discouraged the practice of Native religions. Overall, they distanced students from their own cultures.29 While some children were sent to schools by their parents, one Puyallup woman told an interviewer, "Five generations of Puyallup children were rounded up and taken off to government schools."30 The schools used domestic training for girls – cooking, laundry, and cleaning as well as sewing – ostensibly to educate and train children for work and some schools did place students in domestic service jobs. However, these skills were also a way to imbue children with Western culture, and at least one scholar argues that domestic education for Indian girls was proof of an "underlying federal agenda" intended to indoctrinate "Indian girls in subservience and submission to authority."31

Native American girls were also offered sewing education, but with a very different agenda. Girls at government-run boarding schools were trained to sew, often with the presumption that they would return to reservations and that their training would help them run a "proper household" and care for others who had not been "Americanized." Government-run boarding schools for Indian children have come under intense criticism. The schools forced children to wear Western clothing and speak English and discouraged the practice of Native religions. Overall, they distanced students from their own cultures.29 While some children were sent to schools by their parents, one Puyallup woman told an interviewer, "Five generations of Puyallup children were rounded up and taken off to government schools."30 The schools used domestic training for girls – cooking, laundry, and cleaning as well as sewing – ostensibly to educate and train children for work and some schools did place students in domestic service jobs. However, these skills were also a way to imbue children with Western culture, and at least one scholar argues that domestic education for Indian girls was proof of an "underlying federal agenda" intended to indoctrinate "Indian girls in subservience and submission to authority."31

Like schools teaching white or African American girls, one reason the schools taught sewing to Native American girls was to improve home life. In the Native American context, this often took the form of encouraging the abandonment of traditional habits. Reformers intent on changing Native American communities argued that girls who were trained to keep a home in the Anglo-American style would "make their homes better, and more permanent, besides preventing much gadding about and gossip, by keeping young mothers at home and industrially employed." Jane Simonsen, in her study of attempts to "domesticate" Native American women, writes that "implicit in this condemnation of gossip and transience is the suggestion that isolating women in their homes would keep them from speaking out in tribal councils, preserving rituals and stories, and maintaining kinship ties."32

So, while the African American girls were taught to sew at least in part so they could work as domestic servants, Native American girls were specifically sent home as acculturating agents. This plan was clear in a booklet published by the Office of Indian Affairs in 1911. Entitled Some Things that Girls Should Know How to Do, and Hence Should Learn How to Do When in School, the booklet explained that

the pupil will not go out to work but will return home after finishing the day or reservation boarding school course. It would be well to give actual practice in the homes of some of the people with the assistance of the field matron. There are many old and helpless Indians on reservations who would not resent being assisted in this way. The girl would receive actual experience under difficulties which confront the average Indian and which distress the educated student upon his return from a different mode of life in the boarding school.33

It is not the content – the lesson plans and class projects are the same as in texts that assume a middle-class, white student 8211; but the context of sewing instruction for Native girls that is specific to this Americanization agenda. An Office of Indian Affairs lesson plan noted that the instructor should teach students how to use a modern stove by emphasizing its "advantage over [a] fire of sticks."34 The same booklet said that before teaching students how to make or choose home furnishings, she should investigate "home conditions" and "tactfully suggest improvements."35 In sewing classes, girls were taught to make Western clothing such as shirtwaists and aprons. The extensive sewing curricula outlined in the Office of Indian Affairs publications, therefore, can be read either as a well-intentioned educational program or as a means of coerced acculturation.

Segregated school systems facilitated the process of teaching sewing to African American and Native American girls with a distinct economic and social agenda. While it is harder to find evidence that working-class girls of European ethnicities were treated differently, sewing courses aimed at training future workers can provide some insight into whether, and how, working-class white girls were taught differently than their middle-class counterparts.

Some public schools implemented vocational programs in the late nineteenth century as a response to a perceived decline in family cohesion and virtue. One scholar of urban education notes that administrators questioned whether poor mothers, especially immigrants, "knew or were concerned about inculcating the principles of moral family building in their daughters."36 Middle-class school officials believed providing for a family was women's primary duty and administrators in industrial cities were clear in their belief that sewing lessons would help ameliorate social conditions. Young factory operatives in Fall River, Massachusetts, were among the first to have sewing classes in 1875 because they had no time to learn such skills at home. The New Bedford superintendent of schools argued that it was the lack of sewing skills that caused what he saw to be the "unthrift and ragged shiftlessness of many homes."37 Sewing lessons for working-class girls therefore went beyond basic skills to become a means of improving homes and characters.

Special courses for working-class girls were sometimes noted in the press. In 1896, a New York Times article claimed "How to Make Dresses Inadequately Taught in New York" and argued that such a condition kept "many women from learning a woman's work."38 The author asserted that this lack of gender-appropriate training meant that women were invading the male sphere of work:

Thousands of young women, on leaving school, rush to office, workshop, typewriting and factory work, who cannot sew a button properly, much less mend decently, and very much less make a garment, though they might have to dress in rags because they did not know how to do these things.39

The author hardly distinguishes between industrial and home sewing, at one point implying that at the very least, sewing in an industrial setting is more appropriate for women than for men. He (or possibly she) claimed to have "investigated the possibility of securing instruction for young women who wish to give up factory and shop work for the more homelike occupation of making clothes" and that this switch was justified because "the amount saved in the dressmaking bills of a family more than makes up for the amount earned by one of this class."40 He proposed a publicly-funded dressmaking school that would attract girls who were turned off by the prospect of the poorly paid drudgery of apprenticeship yet could not afford the classes offered at the Y.W.C.A. and elsewhere. His logic was flawed 8211; he assumed a school setting was preferable to an apprenticeship and he did not account for the family that already sewed its own clothing and still needed the daughter or wife's income. The implication, however, was that "the intermediate and very poor classes" required dressmaking education to earn an income and to provide clothing for themselves and their families and that with proper and inexpensive training, they would be able to do so without threatening the livelihoods of men.

Such a school was created about sixteen years later when the Manhattan Trade School for Girls was formed for "the girl pupils of the public schools, who are not able to stay in school after they are fourteen because they are obliged to earn their own living." The students were "taught not only how to make attractive garments for themselves, but a trade by which they can support themselves" through a year-long course in millinery, dressmaking, or machine operation.41 The timing of the course was planned so that after graduation in July, the girls would have some vacation time before the garment season began in the fall.

Such a school was created about sixteen years later when the Manhattan Trade School for Girls was formed for "the girl pupils of the public schools, who are not able to stay in school after they are fourteen because they are obliged to earn their own living." The students were "taught not only how to make attractive garments for themselves, but a trade by which they can support themselves" through a year-long course in millinery, dressmaking, or machine operation.41 The timing of the course was planned so that after graduation in July, the girls would have some vacation time before the garment season began in the fall.

Students at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls bought their own materials and made garments for themselves, which provided incentive as well as hands-on training. Girls in the machine operating class could make as many garments as possible in the time allowed, thereby training them for the speed (and speed-ups) of the factory setting. The dressmaking students, on the other hand, were taught to make fewer but finer quality items. The school was racially integrated and the article took pains to note that "a young colored girl was working yesterday on a deep rose-colored frock and one of the prettiest pieces of underwear in the better-class underwear department was made by another colored girl."42

Two years later, another school was planned, this time by the garment industry itself. Apparently, the lack of sufficiently trained operatives was threatening the future of the trade and so with the cooperation of the mayor, the Dress and Waist Manufacturers' Association intended to form an institution to train workers. Whether this plan worked is unclear, but the demand for such institutions sheds light on at least two things: first, sewing instruction in most New York City schools was not oriented toward a professional or industrial setting and second, specialized sewing instruction was in the interest of employers and at least some students.

Vocational training is a fascinating way to understand race and class politics as experienced by girls, but not all schools were oriented toward wage work. Most schools, in fact, provided a more general, home-oriented curriculum, in which home economics teachers emphasized girls' future domestic needs in their teaching. Moreover, girls who went on to work in the sewing industries would also need to use their skills at home. One textbook writer, who was also the director of sewing in the New York public school system, recognized the tension between training for homemaking and for wage earning. In the end, she felt that the general curriculum should prioritize domestic issues. In the introduction to a basic sewing textbook, she explained:

In the last few years trade and vocational schools have been established where the courses in domestic art received in the elementary schools may be supplemented by a training which will fit the girl to be a successful wage-earner, and consequently elevate her above the body of unskilled workers.

The most important factor, however, in our public-school work is the training for efficiency in the family and in home life. Lessons are taught in domestic economy which will enable the pupils in later life to solve the question of wise and judicious expenditure.43

Focusing on skills for home use hardly eliminated class concerns. Some teachers were very aware of the economic background of their students and at times worked to accommodate the girls' particular needs. In the late 1920s, a home economist published an article in the Journal of Home Economics describing the layette project she directed in her junior high class. She explained that the girls, from a poor community in Denver, often had partial or complete responsibility for younger children in their homes. She therefore sought to teach them a range of skills. The girls made a layette set and learned about feeding, bathing, and other elements of baby care. As part of the project, the girls raised money with bake sales, learned to comparison shop, and did research on childcare. In the end, Wilson claimed that

as a result of this project the girls' purpose in making the layette...some needy family helped them to learn many things concerning child care. They obtained an elementary knowledge of the clothing, care, feeding of babies and learned where information on child care may be obtained....they used skills they had acquired in clothing and food work and obtained in addition to knowledge of how to care for a baby. There was much more interest in making the garments and book because an atmosphere of helpfulness for others was created. Some of the ideals and attitudes the girls developed were: the spirit of helpfulness, unselfishness, industry, and cooperation. 44

In this classroom, the goal was to teach working-class girls to apply their sewing skills to their immediate and presumed future family duties.

Another teacher described a survey she undertook of her students in 1928. The subjects were "working girls" at the Milwaukee Vocational School, aged fourteen to eighteen, who lived at home and went to school part time. She helped them realize that on average, they spent a full half of their own earnings on clothing and she taught them how to make a budget. Eighty percent of the girls reported that they sewed at least part of their own wardrobes, so the assumption was that they already knew at least the basics.45 In the Milwaukee class, the focus was on making a budget, not on learning how to sew, but the message that sewing one's clothing was usually cheaper than buying was evident. Moreover, when the girls realized that clothing costs used up such a large portion of their earnings they were driven to ask such questions as "What would I do if I were living away from home?" and "How could I meet other expenses when my clothing bill alone exceeds my pay check?"46 The author noted with approval that "girls apparently avoid the habit of charging or buying on the installment plan," at least when they shopped with their mothers, as 87 percent said they did. The teacher was obviously aware that attention to the cost of homemade versus store bought clothing and wariness of credit are issues that most working-class girls would continue to face as they got older. In these two cases, the particular needs of working-class girls were addressed in their home economics classrooms without condescension.

While these educators were aware of the particular needs of their students, most home economics textbooks assumed a white, middle-class student who would marry, have children, and keep house. One article opened with the reminder that "90 per cent of our girls will be in their own homes within a few years" and asked "what shall we teach them that will aid them the most when these tasks fall upon their unaccustomed shoulders?"47 In their discussion of finances, text authors incorporated sewing into the larger context of a woman's role as nurturer, budget director, consumer, and producer. Some authors addressed the potential for earning a living through sewing, either independently or in an industrial setting, but they were more likely to focus on how home sewing squeezed more money from family budgets. One textbook told readers, "Girls must begin to learn how to spend wisely, for they will very soon have the responsibility of being spenders. If you make some of your clothing, you will help to reduce the cost."48

Sewing textbooks focused on a standard series of stitches, suggesting projects that became increasingly more sophisticated. Girls were taught to recognize different types of fabric, to assemble and care for sewing tools, to sew simple seams, mend and darn, and to make buttonholes and tricky details like gussets. Some books taught pattern making or how to use commercial patterns, and some assumed that girls would use sewing machines in school or at home.

In addition to their technical content, many of these texts reflected the same values that drove schools to teach sewing in the first place: the authors felt that girls ought to sew. The books are clear that sewing was a woman's duty and girls would need to know such skills when they ran a household. Sewing courses and textbooks also contained more subtle details that informed girls' understanding of their role as girls and women in American culture. Books emphasized the need to be neat, organized, and tidy. They often had girls make doll clothes as practice garments, reinforcing the idea that their central role was as mothers and nurturers. Girls made towels and curtains not only because they were simple projects but also because they were a way to learn how to establish a reputable household. Girls were assumed to have a natural desire to be fashionable or stylish and a need to appear "respectable."

The attitudes prevalent in the textbooks also changed with the times. Books from the 1890s and early 1900s tended to emphasize women's roles in the household. One book from 1908, which may have been intended for home or school use, sympathized that little girl mothers have almost as much trouble as grown-up mothers about their children's clothes" and promised to "show you how to have your dollies beautifully dressed without troubling big people or costing much money." 49 A text published in 1911 urged that students should be set to work making practical items as soon as possible, since "these girls are to become home-makers. They can not be overtrained in the subject in so short a time."50

By the 1910s, authors began to expound on Progressive-era ideas of bringing science and hygiene into the home. For example, a book published in 1916 entitled Clothing and Health: An Elementary Textbook of Home Making is revealing. The authors, well-established home economists, explain that clothing was related to health and well-being and therefore the domain of the woman of the house, telling readers, "Our clothes are important for they help to keep us well."51 Sewing was a way to be organized, clean, and resourceful, but it was also to be fun. Clothing and Health and other texts referred to the pleasure girls could find in making their dresses, the money they could save, and the help they would provide their families. There was little doubt that "sewing is an art which all girls should learn."52

^topSettlement Houses, Scouting, and Clubs

While schools are a logical place to study how, what and why girls were taught to sew, other institutions played a large role as well. For example, settlement houses frequently offered sewing classes and clubs for girls. In 1915, the Jacob Riis House in New York City offered seventeen sewing classes weekly, apparently for young women, in addition to the five weekly sewing clubs for adult women.53 By the 1920s, if not earlier, the sewing courses were taught by students at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, which offered teacher certification in home economics. The Jacob Riis House was located on the Lower East Side, a neighborhood famous for its Jewish and Italian residents, and the clubs at the settlement house reflected this population. The settlement house offered a range of services, from legal help and English classes to social clubs and dances. It may also have served as a vehicle for acculturation. An undated report, most likely from the 1920s, reflected this role in teaching cultural norms. The author wrote:

We offer our children clubs and classes. We offer them play and story hours, and game-rooms. We know that from all this they gain a little in the techniques of cooking or sewing, embroidery or knitting, a little in the training of manners and customs, a little in the building of mind and character, and a great deal of individual and group enjoyment.54

This and other settlements offered adult women's sewing clubs as well. By teaching children and their parents sewing skills along with "manners and customs," institutions such as the Jacob Riis House helped reinforce the idea that sewing was part of being an American woman.

Many girls learned to sew as members of clubs and associations. The Girl Scouts of the U.S.A., founded in 1912 by Juliette Low, offered a range of civic, domestic, and outdoor skills to girls. The Girl Scouts are a fascinating source of information on just how and what American girls were taught about women's roles in the early twentieth century. Overall, it seems that they were offered a wide range of images of femininity. Scouts were encouraged to develop career skills. An early handbook reads, "Really well-educated women can make a good income by taking up translating, dispensing to a doctor or in a hospital, as stockbrokers, house decorators, or agents, managers of laundries, accountants, architects."55 The same book, however, also indicates that girls are distinctly different than boys and should develop those traits that are innately womanly. Early on in the guide, under the heading "Be Feminine," Low wrote:

None of us like women who ape men… Girls will do no good by trying to imitate boys. You will only be a poor imitation. It is better to be a real girl such as no boy can possibly be. Everybody loves a girl who is sweet and tender and who can gently sooth those who are weary or in pain. Some girls like to do scouting, but scouting for girls is not the same kind of scouting as for boys. The chief difference is in the courses of instruction. For the boys it teaches MANLINESS, but for the girls it all tends to WOMANLINESS and enables girls the better to help in the great battle of life.56

The Girl Scout Law stipulated that scouts be pure and dutiful, follow orders, be courteous, cheerful, and thrifty, all of which could be construed as classic pillars of traditional femininity. One way in which girl scouts could learn to be womanly was through homemaking skills. The guidebook has a section on "Housewifery" which reads, "Every Girl Scout is as much a ‘hussif' as she is a girl. She is sure to have to ‘keep house' some day, and whatever house she finds herself in, it is certain that that place is the better for her being there."57 The section on needlework focused mainly on mending and included a photograph of girls sewing, one with a foot-powered sewing machine. The text described sewing as a way of making torn things "all right and serviceable" as well as making "useful presents" and "articles for their hospitals."58 A later edition of the ubiquitous Scout handbook, published in 1920, also praised domestic skills; the "Home Maker" section equated homemaking with patriotism. The author wrote, "Every Girl Scout knows that good homes make a country great and good; so every woman wants to understand home-making."59

The Girl Scouts published a magazine called American Girl that ran articles on a variety of subjects, such as camp skills and international scouting. One regular column covered sewing and clothing and included instructions on how to look "smart" as well as how to make garments. One article from 1928 described how an adult woman wanted to sew but did not know how, having never learned as a girl. She related how she felt when she saw a dress she admired and was informed that a girl made it. The author exclaims that she would love "to be the clever girl who can make it herself – a new party dress, for instance, when a party comes up unexpectedly that you just have to have a new dress for, or lots of simple summer dresses that you can make for very little and that do cost a lot when you have to buy them." She went on to depict a particular dress:

You can make for yourself if you have a tape measure and a pair of scissors and a little patience. It doesn't even require a paper pattern. And once having succeeded with this, you may be emboldened to try something more difficult. Who knows but that before the end of the summer, you'll be making all sorts of charming frocks for yourself, and perhaps for your little sister too!60

The article then described the cost of the required material and the steps for making the dress. As far as its sewing content was concerned, American Girl was very similar to adult women's magazines of the time.

The Girl Scouts are an excellent example of how sewing was a means of teaching values to girls. Scouts were encouraged to clothe themselves and were assured that by doing so they were being frugal, clever, fashionable, and nurturing, all traits that were valued by adults. Home sewing instruction was both a means and an end. On one level, the sewing was a useful and entertaining skill for many girls, but it was also a way to behave like their mothers and other role models.

In addition to these many public or voluntary efforts, there was money to be made teaching girls to sew. While the role of business in encouraging sewing is examined in more detail in a later chapter, two important examples of for-profit ventures demonstrate that companies eagerly sought the girls' market. The first is the Singer Sewing Machine Company, which embraced sewing education on several fronts. Singer supplied schools with machines and included photographs of Singer-equipped classrooms in its instructional manuals. One manual, published in 1914, noted:

The great aim in education is to equip the scholar for his or her future career. One of the surest means to this end, in a girl's education, is to teach her how to use a sewing machine… A girl who has been properly trained in the use of a Singer Machine is not only able to save herself and family much money and time, but is equipped to earn her living, should she be require [sic] to do so, in one of the great sewing industries.61

The same manual included photographs of girls and young women using Singers at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls and the Domestic Science Department of Woodward High School in Cincinnati. Singer offered free sewing classes at affiliated sewing shops, linked its classes to Girl Scout sewing badges, and marketed its products directly to girls. Singer advertisements suggested that by sewing their own clothing, girls would have more clothes than they might otherwise be able to afford but also emphasized that sewing was fun. One such ad offered the testimonial of a happy customer who gushed:

Already I have five of the prettiest dresses I ever had – more than I ever dreamed of having this season...And the materials for all of them have cost just about as much as the price of that one ready made dress I had chosen…. It has been the most fun – choosing the patterns and materials and then planning everything.62

Testimonials are advertising and may or may not come from real customers. What is reliable is how Singer wanted to be perceived.

As a constituency that did not have much expendable income, girls may not appear to be the best audience to target. Singer worked around that problem by appealing to parents' practicality. The above ad explained that the girl in question asked for a Singer as a gift when she could not afford the ready-made clothing she wanted. Moreover, the fact that girls had limited cash was a built-in incentive to sew. Add to that mix the concept that sewing was fun and creative and Singer had a constituency that might remain loyal to the brand in their adult life.

A second example of business involvement in girls' sewing is an extensive club network organized by Butterick. In the autumn of 1906, after the Delineator ran an article describing a sewing club organized by one child's grandmother, the magazine was deluged with requests for help setting up similar clubs. The result was the Jenny Wren Doll's Dressmaker Clubs, named after a girl who sewed doll clothing in Dickens' Our Mutual Friend. Girls were to organize in groups of 6 to 12 with help from an adult "directress" and were expected to establish a set of rules, charge modest dues to help pay for materials, and elect officers. When they sent in a list of members to the Delineator, the girls received an official club charter, membership pins, and free patterns for doll clothes. Girls responded eagerly: in approximately one year there were more than 30,000 members in clubs throughout the U.S., its territories, and foreign countries.63 The Delineator ran regular articles describing their work and offering project suggestions. "Junior" club members were instructed to focus on doll clothing, whereas "seniors" sewed for themselves. All members were encouraged to sew items to sell at a fair (organized by members and patient parents) and donate the proceeds to charity.

A second example of business involvement in girls' sewing is an extensive club network organized by Butterick. In the autumn of 1906, after the Delineator ran an article describing a sewing club organized by one child's grandmother, the magazine was deluged with requests for help setting up similar clubs. The result was the Jenny Wren Doll's Dressmaker Clubs, named after a girl who sewed doll clothing in Dickens' Our Mutual Friend. Girls were to organize in groups of 6 to 12 with help from an adult "directress" and were expected to establish a set of rules, charge modest dues to help pay for materials, and elect officers. When they sent in a list of members to the Delineator, the girls received an official club charter, membership pins, and free patterns for doll clothes. Girls responded eagerly: in approximately one year there were more than 30,000 members in clubs throughout the U.S., its territories, and foreign countries.63 The Delineator ran regular articles describing their work and offering project suggestions. "Junior" club members were instructed to focus on doll clothing, whereas "seniors" sewed for themselves. All members were encouraged to sew items to sell at a fair (organized by members and patient parents) and donate the proceeds to charity.

The Jenny Wren club network was ingenious brand development. Butterick would surely garner future customers as the Jenny Wren girls matured and graduated from doll clothes to dressing themselves and their own families. The articles describing the original Jenny Wren club casually mentioned Butterick products:

The money in the treasury would pay for the patterns they should need for the dolls' clothes, for patterns were most necessary. Even Jenny Wren, who was the very cleverest dolls' dressmaker that ever was, had to use patterns. Only there were no Butterick patterns in her day, so she had to shape them herself, and they cost her poor, crooked little back many aching hours. The club that had named itself after her was very much better off; for nowadays one could buy for very little money, the very smartest of patterns, made expressly for dolls.64

In addition to being a novel business model, the Jenny Wren network was means of social modeling. The clubs echoed the standard set-up followed by adult clubs. By electing officers, charging dues, keeping minutes, and sewing in the interest of charity,

they were emulating middle-class club women's procedures and goals.

In addition to being a novel business model, the Jenny Wren network was means of social modeling. The clubs echoed the standard set-up followed by adult clubs. By electing officers, charging dues, keeping minutes, and sewing in the interest of charity,

they were emulating middle-class club women's procedures and goals.  For example, the Allston club donated items they made such as sheets and diapers, as well as the cash proceeds of their fairs, to the Boston Floating Hospital. Butterick was nurturing not only its customer base but also the social structures that that base valued. By encouraging girls to sew, the company, the organizations that accepted the girls' charitable efforts,

and the families who supported the clubs transferred values to the next generation.

For example, the Allston club donated items they made such as sheets and diapers, as well as the cash proceeds of their fairs, to the Boston Floating Hospital. Butterick was nurturing not only its customer base but also the social structures that that base valued. By encouraging girls to sew, the company, the organizations that accepted the girls' charitable efforts,

and the families who supported the clubs transferred values to the next generation.

Know How to…

If the apparatus of sewing education can be considered to be a cultural artifact, full of meanings about a particular era's gender, class, and racial roles, then the courses, textbooks, dolls, and magazines created for girls reflect cultural expectations. We also need to analyze what girls were actually capable of sewing. Understanding what they thought about all of this sewing is yet another matter. It is possible to ascertain at least some "reader response" or "real life" aspects of girls sewing through sources such as workbooks, club minutes, and dresses. They can help us understand how girls felt about sewing and what they were capable of making. Interviews also help us gain insight into (adult memories of) girls' thoughts on sewing.

A textbook can tell us what and how well a girl was expected to learn to sew in school. For example, girls were consistently taught basic stitches and techniques such as buttonholes, gathering, and hemming. After teaching these elements of hand sewing and depending on budgets and the students' ages, some schools also taught girls to use sewing machines. Textbooks taught a progression of projects, often starting with aprons and moving to full-size dresses. The timing of this progression was variable. One book, published in 1893, outlined an ideal schedule that included six years of sewing, starting in kindergarten. In the first year, girls were expected to be able to make aprons and underwear; by the third, they might make a dress for themselves.65 Older girls could work faster, especially when using a machine. An article by a high school teacher written in 1919 acknowledged that "the amount of sewing that should be accomplished in the first year of high school is always an open question." For a class meeting five hours a week, she required thirteen garments including undergarments, a "kimono" dressing gown, and two blouses in the first semester.66

Some textbooks in archival collections have the one-time users' names inscribed inside, so it is possible to determine that real girls used them. Otherwise, it is hard to tell which books were used and impossible to judge whether they are realistic guides to what girls could make. Other sources, however, provide direct links to real people. A number of workbooks made by school-aged girls and a set of lesson plans drawn up by a high-school sewing teacher provide clues to what girls were actually taught and what they made.

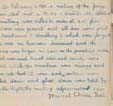

Stella Blayly and Gertie Blair put together workbooks of their sewing lessons. The books are not dated but are estimated by an archivist to be from between 1880 and 1900. There is nothing to indicate that the two girls were at the same school, but both follow a similar pattern that reflects the lesson plans in sewing textbooks. There is something magical about these workbooks.

They are a testament to the work and concentration of some little girl. To the modern observer, the level of workmanship is extraordinary. Each page has a particular lesson with some text plus a fabric sample attached with rusting pins. The girls' lessons included basic stitches, hemming, patching, making buttonholes, and gathering fabric into a cuff or waistband. Stella's work is better than Gertie's – her stitches are tiny and her gathering sample is stunning, with tight even stitching. Judging from her handwriting and endearing misspellings, Gertie may have been younger than Stella, which makes her accomplishments all the more impressive.67

Stella Blayly and Gertie Blair put together workbooks of their sewing lessons. The books are not dated but are estimated by an archivist to be from between 1880 and 1900. There is nothing to indicate that the two girls were at the same school, but both follow a similar pattern that reflects the lesson plans in sewing textbooks. There is something magical about these workbooks.

They are a testament to the work and concentration of some little girl. To the modern observer, the level of workmanship is extraordinary. Each page has a particular lesson with some text plus a fabric sample attached with rusting pins. The girls' lessons included basic stitches, hemming, patching, making buttonholes, and gathering fabric into a cuff or waistband. Stella's work is better than Gertie's – her stitches are tiny and her gathering sample is stunning, with tight even stitching. Judging from her handwriting and endearing misspellings, Gertie may have been younger than Stella, which makes her accomplishments all the more impressive.67

Older students made workbooks as well. Several were made by a woman named Lucy Pierce, who studied at the University of Rhode Island and planned to become a teacher. She put together a detailed set of notebooks, two dated 1914. One is entitled "Plain Sewing" and includes how to use a sewing machine, directions for making an apron, how to hem items, and pieces of fabric. Some of the notebooks include envelopes with fabric samples labeled "Teacher's Models."  Pierce later taught at the Technical High School in Providence. Her effectiveness as a teacher is evident in a notebook created by Maude Perrin Streeter, dated 1921 and entitled "Domestic Arts Dressmaking with Lucy Pierce." Streeter included lists of skills and samples of her sewing and embroidery stitches.68 These notebooks indicate what was taught in domestic arts and sewing classes, and what students were capable of doing.

Pierce later taught at the Technical High School in Providence. Her effectiveness as a teacher is evident in a notebook created by Maude Perrin Streeter, dated 1921 and entitled "Domestic Arts Dressmaking with Lucy Pierce." Streeter included lists of skills and samples of her sewing and embroidery stitches.68 These notebooks indicate what was taught in domestic arts and sewing classes, and what students were capable of doing.  Judging by the quality of work in Pierce's and Streeter's notebooks, they were capable of a great deal, from understanding textile manufacture and designing patterns to invisibly mending holes, and constructing sophisticated garments. Moreover, the level of organization evident in Pierce's teaching notebooks indicates how seriously she took her work.

Judging by the quality of work in Pierce's and Streeter's notebooks, they were capable of a great deal, from understanding textile manufacture and designing patterns to invisibly mending holes, and constructing sophisticated garments. Moreover, the level of organization evident in Pierce's teaching notebooks indicates how seriously she took her work.

Marian Goodman | Read transcriptThe range of difficulty and variety of projects in home economics classes is also evident in women's recollections of what they made. Edith Kurtz, who had sewing in eighth grade in Michigan around 1918, does not recall doing much more than mending.69 Meanwhile, Florence Epstein's Rochester, New York, sewing teacher required the girls to make middy blouses to wear for their eighth grade graduation in the mid-1920s.70 Many girls were required to make their own eighth-grade graduation dresses. Making one's own dress was a practical way to demonstrate skills learned in school. It was also a way to clothe girls in a relatively uniform way without demanding much expense on the part of their families.

Because children's clothing often wore out or was handed down many times, it rarely survived for historical analysis. The exception is clothing worn for special occasions such as these graduation dresses, several of which are in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. Marie W. Fletcher made her graduation dress in 1914 of white batiste trimmed with lace, tucks, and embroidery.70bis Fletcher was taught sewing in elementary school from the third grade through the eighth, and made this dress at P.S. 22 in Flushing, Queens, when she was twelve and thirteen years old. Another dress, made of white cotton voile with net around the neck and with short puff sleeves, was made by fourteen-year-old Anna Frankle for her graduation in 1918.71 Anna's sister Helen made her own dress for her graduation in 1926. Years later, Helen and Anna noted, "It was customary for each girl to spend a year making her graduation dress in the eighth grade."72 Whatever their feelings about these projects as girls, these women kept their dresses for years and eventually donated them to a museum.

Florence Epstein Excerpt #2 | Read transcriptMany girls made dresses and other garments outside of the classroom. Helen Schwimmer made a dress when she was fourteen using her mother's sewing machine. After she made her middy blouse in school, Florence Epstein made curtains for the kitchen. She also made something for her mother at least once and at one time, made scarves for her brother (and then for at least a dozen of his friends). Mostly, however, she made clothing for herself.73

Helen Schwimmer | Read transcriptAnother way of understanding what girls were capable of sewing is to look at sources from the clubs they formed or joined. Some girls may have belonged to informal clubs in their neighborhoods. Helen Schwimmer remembered a group she belonged to as a young girl in Toledo, Ohio, saying, "We used to have a little sewing club, even with the boys."74 She recalled sitting in a circle on the porch with other children from the neighborhood. They were able to buy small but desirable dolls (with china heads no less) for very little money and she would make clothing and hats for the dolls while the children sat and waited for her to finish.

Other clubs, such as the Jenny Wren clubs discussed earlier, were more formally organized. A group of girls in Allston, Massachusetts a suburb of Boston), organized their own Jenny Wren club in 1908. When the club formed the members ranged in age from eleven to fourteen, most being twelve and thirteen. The club kept charming and meticulous records. Entries for three meetings in 1908 include what the girls were making:

October 1, 1908

The President is to make a handkerchief case. Ruth, an apron, Pauline a pin case, Beatrice a sachet, Ida a sofa pillow and Constance dusters.

October 8, 1908

Ruth's apron is almost done.

October 22, 1908

Pauline has dressed a pretty doll and made a sachet. Emilie is making a handkerchief, Ruth another apron, while Muriel has finished her handkerchief case. Ida has made good headway on her sofa pillow...Everyone but Bea had sewing, but as she was provided with some by Dorothy we all had some and we sewed about an hour. Refreshments were served and the meeting adjourned at 6.00 being wound up with a game of Post Office.75

Following the suggestions from Butterick, the Allston Jenny Wrens held an annual fair at which they sold their products and donated the proceeds to a children's hospital in Boston. In addition to showing what they could make, their records indicate that these girls used sewing as the basis for sociability and charity, a pattern that echoed the activities of thousands of middle-class women.

The Girl Scouts provide another way to understand the expectations and realities regarding girls' proficiency in sewing. Early on in the organization's history, there were three levels of scouts, and to be a "First Class" scout, girls had to make a skirt or blouse by themselves. The scouts also offered sewing badges and as of 1920, there were two, "Needlewoman" and "Dressmaker". According to sales records, these were among the most popular. Between 1913 and 1938, the national suppliers sold 177,935 of the two categories combined. In comparison, the suppliers sold 156,256 "Cook" badges, 31,398 "Swimmer" badges, and 26,301 "Naturalist" badges over the same time period.76 Judging from this evidence, we can presume that tens of thousands of Girl Scouts were able to perform at least the basic skills required for the badges. Some may have learned to sew as part of their scout activities and others probably knew how to sew when they joined the organization. In fact, when Marion Goodman joined the Campfire Girls, a different organization than the Girl Scouts but with a similar structure, she chose to do other projects because she already knew how to sew.77 The badges may have been popular in part because many girls already knew how to sew when they joined the scouts, but the popularity of the badges shows that sewing skills were widespread.

Contests provide another peek into the expectations of adults regarding girls' sewing skills. The state meeting of the Nebraska Girls' Domestic Science Association ran a sewing contest for girls. The 1909 guidelines listed several categories, including:

- A sewing apron, entirely hand made, no machine work.

- A "Domestic Science" apron; machine made, may have some hand work.

- Work apron (with sleeves, and buttoned in the back) including hand and machine work on the garment.

- Washable sofa-pillow cover with top and back sewed together on three sides.

- Plain wash shirt waist.78

Prospective contestants were further reminded that "even stitches, strong sewing, and neat finish are of greater importance than expensive trimmings. When aprons and waists are finished there should be no raw nor unfinished seams, no basting threads, and no gathers which have not been stroked…"79 A less stringent "Style Show" was organized by the Girl Scouts of Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1926. Forty-one girls wore dresses they had made before representatives of the Waterbury Institute of Arts and Crafts, who judged them "not only on the sewing but on becomingness of the material, the color and the style."80 The seven winners – none of whom can be older than twelve or so – wear attractive, if simple, dresses, and one wears a hat she made as well. Such contests were popular and the State Fair in Nebraska continues to hold sewing contests today.81

^top"How I hate sewing!"

Girls sewed at home, in clubs, and at school. Their mothers and teachers had varying attitudes toward sewing and their experiences varied according to class and race, but if we are seeing to understand the range of cultural meanings of sewing, we also have to try to see what sewing meant to the girls themselves. Did girls like to sew? Why or why not? And what did it mean to them?

Surely, many enjoyed the process or at least its results. Florence Epstein told me that she sewed because it allowed her to have pretty things, and recalled specific outfits with pride, including a wool suit she made as a teenager. She said, "You could pick up a piece of material for almost nothing, very little money, and that meant that I could make myself a dress anytime I wanted a new dress. I didn't have to worry about having the money to go out and buy one. I could just make one."82

Even girls who liked to sew did not want to do so all the time. The Jenny Wren club in Allston, Massachusetts, was ostensibly formed with the goal of sewing, but it is clear that the girls often preferred to socialize. Minutes from early meetings indicate that the needlework was often abandoned rather quickly:

February 6, 1908

There was no business discussed and the sewing was began [sic] as soon as the preceding weeks [sic] report was read. Small cakes and candy were served while the members were sewing and when it was dark curtains were pulled down and ghost stories were told by candle-light.

What makes the above passage especially revealing is that whoever took the minutes wrote the words "at last" right before it was dark" and then, apparently embarrassed by her eagerness to get on with the fun, struck them out. Another record echoed this sentiment:

What makes the above passage especially revealing is that whoever took the minutes wrote the words "at last" right before it was dark" and then, apparently embarrassed by her eagerness to get on with the fun, struck them out. Another record echoed this sentiment:

February 20, 1908

All had there sewing [sic]. Refreshments were served. Miss Woodbury then left. As we did not seem to want to sew then a little business was talked and it was decided that we would have a fare [sic] to make more money. There was a long discussion over what we should have, but we finally decided. The meeting was adjourned at 6 o'clock. All had a very merry time.83

This ambivalence toward sewing persisted as the club members grew older. The minutes from a club meeting in 1913 document that the majority of members agreed they should sew instead of playing card games at meetings and they proceeded to play more cards once there was "no further business" to discuss.

This ambivalence toward sewing persisted as the club members grew older. The minutes from a club meeting in 1913 document that the majority of members agreed they should sew instead of playing card games at meetings and they proceeded to play more cards once there was "no further business" to discuss.

Sewing can be quite challenging, especially for young fingers or when teachers and parents set high standards of neatness and workmanship. Given the quality of work in girls' sample books, the frustration level most likely ran quite high. Helen Schwimmer, who sewed extensively and with much pleasure throughout her life, spoke vehemently of the frustration she felt as a child. Her mother had very strong opinions about how things should be made and Mrs. Schwimmer has "memories of ripping out all of the time… At that time it used to kill me as a child. And my mother would never tell me just to leave it go. It had to be done right."84

While these examples show that many girls preferred to play games or disliked spending hours working on one item, others flat-out disliked sewing. For them, the task ranged from a boring job that kept them from other things they enjoyed to an extraordinarily frustrating chore forced upon them by their mothers or teachers. In a diary entry for August 7, 1915, thirteen-year-old Marion Taylor wrote "I had to sew a lot this morning. Mother says if I don't finish that negligee, before we go to the beach I'll have to do it there! I don't take any interest in my clothes at all and it makes mother so mad."85 Marion's attitude toward sewing did not change; when she was seventeen, she wrote:

In sewing I was making a pair of drawers – they were in two pieces and I hadn't the slightest idea how they went together and when I went to join the pieces together, I found that the ruffles, instead of being around the legs, ran up the middle of the front and back! My teacher thinks that I'm an inspired idiot. I've spent four periods, ripping those ruffles out. I spend most of my time in sewing ripping things out. How I hate sewing. It nearly drives me wild.86

Shortly thereafter she noted:

Mother won't let me read. I have to sew. I simply hate to sew, and I don't accomplish anything. I am so lazy. I don't like to move around, I hate housework. I just like to read and write. It's awful. Oh dear. Why am I so awful. Why wasn't I a man. I suppose I would be a poor sort of man, too.87

Marion obviously associated sewing with other domestic labor and with "women's work," which she thought she might have avoided had she been a man. For her, sewing was stultifying. She would much rather read or write in her copious journals, which her mother apparently considered "the epitome of all that is foolish, impractical and idle."88 Marion's mother seems to have had conservative ideas about marriage and women's roles. She apparently told her daughter that when a woman marries, she must submerge her personality."89 She also struggled financially after her husband left her, and it is possible that she considered sewing not only something women ought to do but a necessary means of saving money.

Teenagers were not the only ones expressing doubts about the virtues of sewing. Some home economists were also skeptical about the need for sewing in women's lives. Greta Gray, a home economics teacher in Laramie, Wyoming, expressed concern that girls' options were limited by their education. She recognized that many young women would leave school early to work, and therefore supported vocational training, but she expressed concern that many students were getting too much training in home economics, and feared that girls' education would be skewed in favor of homemaking skills. She wrote that home economics

seems to make matrimony the sole aim of girls. If they take vocational home economics work they cannot in most cases take any other vocational work, their only way of earning a living will be by housekeeping, they will not always freely choose marriage, for marriage will be the only course open to them.90

Instead, she argued, girls who want homemaking training should receive it, but others should be given a wider variety of options. Gray, who we might assume to be more traditional in her outlook because of her rural setting, nonetheless argued that "woman has given, and has received, by stepping out from the home."91

Another teacher doubted the assumption that sewing was the best course of action for her students. By the 1920s, when more women worked outside the home and purchased clothing instead of making it, home economics teachers began to acknowledge that sewing was not always the best use of a woman's time. One educator outlined an assignment she had arranged for her students in which they compared the prices of ready-made clothing to garments they could make, designing a system for calculating the cost of home-made garments to include the woman's labor. The students came up with a "price of labor per hour" reached by dividing the cost of materials by the number of hours spent making the item, and concluded that it does indeed pay to sew at home, but only if there is no other work which pays more.92 Texts and educators therefore echoed changing attitudes about sewing, which in turn reflected changes in women's roles.

^topConclusion