Chapter Two

"Boundless Possibilities"

In 1922, a magazine article urged readers to order a pattern for a "popular, picturesque dress for the girl of sixteen." The dress could be made in a variety of fabrics, with different shaped collars, and with or without sleeves.1 The article claimed this style had "boundless possibilities," a reference to the flexibility of the design but also a reflection of a particular understanding of home dressmaking at that time.

A sixteen-year-old might have sewn that particular dress for a range of reasons: she might not have had the cash to buy a more expensive ready-made dress, it might have assigned in her home economics class, she might have wanted to wear something unlike or similar to her friends' outfits, or she might have simply enjoyed sewing. Regardless of her specific motive, she was participating in a long tradition of women's home sewing that brought with it many practical and symbolic meanings. Although sewing could support traditional gender ideology, it did not always or automatically do so. Sewing is a skill upon which reasons and goals are imposed by the user. If some women used sewing to support conservative ideas about their domestic and social role, others wielded needle and thread to challenge such ideas. Moreover, one individual could pursue multiple agendas with one project. This chapter explores these challenges by women from a variety of ethnicities, regions, and socioeconomic positions.

For many women, sewing served as a creative outlet and a tool for self-definition. A teenager could make one dress as proof of an appropriately domestic education and another – using the same pattern – to shock her mother. Sewing could also provide a way for women to earn a living or at least make some supplemental money, a crucial skill in an economy that offered few options to women, especially those who were rural, poor, and not white. We have seen that sewing could be used to enforce class and ethnic hierarchies, but it was also a way to express ethnic and racial identity. Sewing also provided opportunities to enjoy other women's company, encouraged individual style and taste, and offered a source of pride. Home sewing thus moved beyond its functional role as housework to become a means of self-expression, independence, and pleasure. In many respects, it was a way to transform traditional roles and understandings of women's domestic labor.

^topMore than Pin Money

The most common motivation behind home dressmaking was economy. Sewing at home was usually cheaper than buying ready-made clothing, even though most families bought as well as sewed their clothing in some combination. By making garments at home, a woman fulfilled certain expectations about her role in the family as nurturer and producer. Sewing was part of housework and satisfied notions of virtuous thrift.

The flip side of household thrift was the leverage women gained over household financial dynamics by sewing at home. Essentially, sewing was a subtle yet effective way to challenge traditional gender strictures regarding wages and household expenditures. As a way to save money, home dressmaking played a major economic role in a household. It fit in with raising chickens and selling eggs, saving money by canning homegrown vegetables, or bargaining with the grocer. Women who did not earn wages or who earned less than husbands, fathers, and sons were still economic agents in a household. Sewing skills gave women the ability to reduce cash expenditures whether they earned money themselves or not. Even the federal government was aware that sewing could affect domestic power relations, concluding a survey by noting:

As long as the woman at home has no direct source of income and her chief duty is in caring for the home and its occupants, she will, no doubt, consider that making at least a part of the clothing for the family is a wise way of ‘stretching' the family income.2

For many women, however, the benefits of sewing went beyond these practical concerns. Women who were not professional dressmakers could still earn some money sewing for others who did not have the time, skills, or resources to make their own clothes. Many women who did not work for wages on a regular basis were able to supplement their income by sewing for others. For example, as a member of a middle-class southern family in the late nineteenth century, there were few socially acceptable ways for Margaret Drummond to earn a living, but Drummond, who never married, depended on the income she received for cleaning, sewing, and quilting for friends and family.3 Other women ran informal dressmaking businesses from their home: Beulah Steward made dresses for local customers during the 1910s until creditors seized her sewing machine and eliminated her income of up to $2 a day.4

The Woman's Institute published stories sent in by women suffering "financial reverses" who turned to sewing to earn extra money or support themselves entirely. Mrs. John Williams of Wilson, North Carolina, claimed to have supported her family by sewing for neighbors after her husband's business failed, and the widowed Agnes Gordon of Detroit maintained five children doing the same. If true, the testimonials are excellent examples of how women used sewing as an alternative or supplement to wage work. If invented as advertising, they show what the institute believed readers would find compelling. There was also a perky insistence that these skills were a route to independence – graduates never seemed to work for someone else or take in industrial work but instead sewed for neighbors or owned their own businesses. Such stories tacitly acknowledged that women could manage without a male breadwinner. Home sewing was still "work" but instead of unpaid drudgery, it was presented as a respectable and interesting way of earning a living. After all, the testimonials were in an article entitled "Women Served and Made Happier."5

This sort of informal business should be differentiated from piecework, for which women worked at home assembling garments for an industrial producer. As housework, home sewing was indeed part of the gender-specific domestic maintenance that Eileen Boris argues supported exploitative industrial homework.6 Like piecework, an informal dressmaking business would probably provide a woman with a low and inconsistent income, but it could at least protect her from unscrupulous managers who were known to find nonexistent mistakes and deny a seamstress her pay. It was also an option in rural areas where there was no piecework to be found. While imperfect, a cottage sewing industry was a way for women to earn some money outside of formal wage work and it allowed mothers to be at home with children.

^topPleasure in Sewing

The "boundless possibilities" associated with sewing go far beyond economics. Sewing could also challenge understandings of domestic labor by turning work into pleasure. Sewing was often a source of creativity, pride, and accomplishment. Because it was such a part of women's everyday lives, some may not have taken it seriously as a form of personal expression. Others simply saw it as a chore, but some were very aware of the pleasure they derived from sewing.

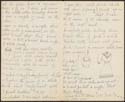

In her journals that also served as newsletters to friends, Lilla Bell Viles-Wyman often described the clothing she made for herself and her friend Lon. A young woman studying dance in New York in the 1890s who supported herself as a music teacher and performer, Viles-Wyman was aware of the skill and artistry that went into sewing:

In her journals that also served as newsletters to friends, Lilla Bell Viles-Wyman often described the clothing she made for herself and her friend Lon. A young woman studying dance in New York in the 1890s who supported herself as a music teacher and performer, Viles-Wyman was aware of the skill and artistry that went into sewing:

Oh! Such a warm day! Dressmaking without – without anything I need – no patterns, no tape measure. Cut my skirt partly by guess & partly by measurement taken with a string of my black dress - cut the waist by the "guess" pattern that I made my practicing waist by - Lon thought it so pretty, concluded, without anything to go by, I better "guess again" by it.7

Viles-Wyman's dress was apparently a great success. A few entries later she wrote, "Monday night I wore my new gown… They all liked it very much…"8 She received commissions as well. A subsequent entry reads "Lon is very much taken with my ‘guess' patterns and tried on my waist, & Thursday I'm going to her house to cut her a blue percale by my pattern."9

An acute observer of fashion, Viles-Wyman commented on styles she admired in shop windows and operated on the assumption that her friends were also capable of replicating the commercial designs. Shirtwaists, for example, required very specific detail.

She alerted her friend, "Lovely Lady! When you make your shirt waist to have it ‘real swell' it must have yoke back & front 8211; a breast pocket & cuffs that turn back. I price them at Atkins $2.75–$3.50, $4 and $4.50 for cotton ones."10 Years later, others did the same. Jane Dunn would go shopping with her mother and aunt. Her aunt would admire something in a store window and say, "I can make that!" Dunn's mother often had to sew for economic reasons, but she also took pride in her skills.11

An acute observer of fashion, Viles-Wyman commented on styles she admired in shop windows and operated on the assumption that her friends were also capable of replicating the commercial designs. Shirtwaists, for example, required very specific detail.

She alerted her friend, "Lovely Lady! When you make your shirt waist to have it ‘real swell' it must have yoke back & front 8211; a breast pocket & cuffs that turn back. I price them at Atkins $2.75–$3.50, $4 and $4.50 for cotton ones."10 Years later, others did the same. Jane Dunn would go shopping with her mother and aunt. Her aunt would admire something in a store window and say, "I can make that!" Dunn's mother often had to sew for economic reasons, but she also took pride in her skills.11

Jane Dunn | Read transcript

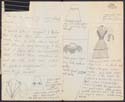

Lilla Bell Viles-Wyman took pride in her ability to make desirable dresses for herself and others, taking the time to make sketches of her ideas and pin samples of fabrics into her journals. Several decades later, Ethel Whiting,

a middle-class woman in California who sewed for her college-bound daughter during the 1920s expressed similar feelings:

Lilla Bell Viles-Wyman took pride in her ability to make desirable dresses for herself and others, taking the time to make sketches of her ideas and pin samples of fabrics into her journals. Several decades later, Ethel Whiting,

a middle-class woman in California who sewed for her college-bound daughter during the 1920s expressed similar feelings:

"Fortunately sewing is my bent (if I have one)! People need to express themselves and sewing expresses me… It was fun to whiz along on my new (second hand) sewing machine from eight-thirty in the morning until five o'clock each day – with only a cracker and a glass of sherry for lunch."12

Whiting could have presumably bought at least some clothing, but she found pleasure in the process of choosing fabric and making the garments. She wrote about the fun of finding "wonderful remnants of the best material" and "putting my ingenuity to work."

This sense of pleasure and pride in sewing started early. Harriet Lange Hayne made a dress for her eighth grade graduation from P.S. 25 in Brooklyn in June 1920. The white cotton dress was quite stylish for its time and was made with tiny stitches and sophisticated seams. Decades later, Hayne donated the dress to a museum with the following note:

The girls in my 8th Grade class were required to make their own graduation dresses. We had had a class in sewing and I remember learning the various stitches and how to turn a French seam. I recall buying the pattern and the material, cutting the fabric, and the many evenings spent sewing while I sat around the dining room table with my parents and brothers. I was fortunate to win the prize for the best made dress: a gold thimble.13

The dress was so important to Hayne that she recalled making it – and being rewarded for her work – when she was ninety-one.

Contests organized by magazines, state fairs, industry, and schools to promote sewing often placed a high value on creativity.

Many competitions rewarded neat work such as Hayne's dress, but others went further and asked contestants to submit original designs for garments. The winners of the 1922 Woman's Home Companion contest for the best "Wearable Dress" won praise and saw their ideas made into commercial patterns and sold by the magazine.

The first place winner was Miss Marion W. Bea of Brooklyn. Bea was commended for her design's "variety; its adaptability to changing styles; its economy; its simplicity of construction; and its becomingness." Contestants sent in "hundreds and hundreds of designs," many as sketches but also as miniature models and full-blown dresses. 14

Contests organized by magazines, state fairs, industry, and schools to promote sewing often placed a high value on creativity.

Many competitions rewarded neat work such as Hayne's dress, but others went further and asked contestants to submit original designs for garments. The winners of the 1922 Woman's Home Companion contest for the best "Wearable Dress" won praise and saw their ideas made into commercial patterns and sold by the magazine.

The first place winner was Miss Marion W. Bea of Brooklyn. Bea was commended for her design's "variety; its adaptability to changing styles; its economy; its simplicity of construction; and its becomingness." Contestants sent in "hundreds and hundreds of designs," many as sketches but also as miniature models and full-blown dresses. 14

A few years later, the New York Times sponsored a nationwide contest for schoolgirls in 1928 and 15,000 girls submitted dresses. The girls could pick from nine basic designs and were judged according to standards suggested by the United States Department of Agriculture.15 The U.S.D.A was concerned about dwindling interest in sewing by the late 1920s, but these contests served more than one purpose. In addition to promoting sales or domestic skills, sewing competitions encouraged and rewarded women and girls for their creativity and talent. The editors of the "Wearable Dress" contest noted, "It's a pity we couldn't show some of the other dresses, for they had, many of them, real originality" and they listed a number of "honorable mentions" in addition to the first- and second-place winners. True, it served the magazine to engage readers, but the fact that the editors valued creativity as well as straightforward sewing skills speaks volumes about sewing as a source of pleasure and pride.

It is easy to see how wealthy and middle-class women who did not need to sew for survival might see sewing as a hobby, but working-class women also sewed for pleasure. Rebecca Sharpless argues that for poor women, sewing was often one of the few ways they could bring some beauty into their lives. She writes, "Many women actually enjoyed sewing, to a point; it was an exercise in creativity, which they rarely had other opportunities to express."16 For example, Mexican women in Texas enjoyed crocheting decorative pieces for their homes. One woman recalled, "Even poor women could buy thread at three cents a ball, and she and her relatives decorated plain sheets when they could not afford other goods, adding crocheted borders to their sheets because they had no bedspreads."17 Recent immigrants also used their skills to make fabric valances and other decorations that could brighten a crowded tenement apartment.18

Some forms of needlework were more pleasurable than others. Marjorie Durand recalled her mother taking rare breaks from running a farm household to do "fancy work" such as crochet or tatting, noting that the household sewing "needed to be done" but fancywork was more relaxing.19 Myrtle Calvert Dodd recalled how her mother quilted so much that the house was not always as clean as expected; sometimes when Dodd and her siblings came home their mother would ask them to finish the housework "because she'd be sewing or quilting."20 Quilting could also have deep personal meaning. After her husband died, Jewel Jimana Woods made four quilts out of his suits and gave one to each child.21 These forms of sewing were clearly an escape from everyday chores. By producing colorful quilts, tatted lace, or embroidered pillowcases, women could dress up their modest homes with objects that had personal meaning.22

Sewing and related arts were also a way for women to form a sense of community. The Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement offered numerous clubs for adults and children, including separate Mother's Clubs for Italian and Irish members.23 At least part of the clubs' activities was to sew items that were sold in conjunction with the girls' sewing clubs. Florence Epstein's Italian neighbor, who made piecework buttonholes for a living, would help Epstein with her own buttonholes when she was a girl.24

Magazine writers encouraged community sewing. The Delineator counted 25,000 girls in its Jenny Wren Dressmaker's clubs by 1908.25 The Woman's Home Companion urged readers to "pool your sewing to save money and lighten work" and offered a series of free leaflets on "The How-To's of Community Sewing."26 Forming a "sewing cooperative" could save members money by buying materials in bulk and sharing patterns. It would also be fun: "Leaving out the delightful social possibilities," asked the author, "doesn't it seem efficient for each woman to concentrate on the part of the work that she best likes doing?"27

Overall, while the majority of women sewed in order to save money, many of them also enjoyed the process and its results. The authors of the Bureau of Home Economics survey admitted that they regretted not asking women whether they liked to sew. However, they noted, "This reason was volunteered by many women and indicates that not all are sewing entirely because of economic reasons."28 Those anonymous respondents went out of their way to remind the survey takers that they took pleasure in what many viewed as a purely practical task.

^top"Clothes that are mine"

By sewing their own clothing women could make choices and develop designs that suited their tastes, afford higher quality fabrics, and fit garments to individual bodies. This interest in individuality appears repeatedly in magazines, diaries, and interviews and was beautifully expressed by Rachel Middlebrook, a gleeful Women's Institute graduate, when she claimed sewing gave her "the ability to express my own personality in clothes that are mine and not to be duplicated."

Middlebrook's ebullience served the Women's Institute well. Institutions that depended on home dressmakers were eager to tout the pleasurable dimensions of sewing. Middlebrook raved about the confidence one could gain by learning to sew and claimed that after making a "One-Hour Dress" (which she admits took her a day), "I was ready for any attempt...At last I could declare, in awed happiness, ‘I can make anything!'"29 A fabric industry leader countered concerns that women were buying all of their clothes with two examples of women who enjoyed sewing. "Miss A." worked in a department store and said she sewed in part to have things that were "different." "Miss B.," a chemical engineer, told him, "I simply won't have anything just like some other person's and I will not pay the prices that one must pay to get fine materials in dresses of real individuality."30

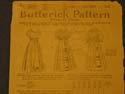

Margorie Durand | Read transcriptWhile self-serving, this emphasis on creativity began before industries became concerned about their clientele's fading interest. From the start, the pattern industry was aware of the possibilities for variety and personal expression inherent in home dressmaking. Many patterns were designed to offer variety. For example, a simple blouse pattern would often come with extra pieces so that the consumer could choose a particular collar or sleeve detail that suited her needs and tastes. Patterns were advertised with these options. A typical Butterick pattern for a "Ladies' Shirt-Waist or Shirt" was "to be made with straight or turn-up cuffs and with a standing or turn-down collar."31 The picture showed one version of the blouse, while a smaller image demonstrated another combination of collar and cuffs. In the 1890s, the fashion editor of the Ladies' Home Companion responded to a reader's letter by encouraging personal adaptations of commercial patterns:

You make the mistake of most home dressmakers in thinking that you just follow patterns exactly. Designs are given from issue to issue to suggest. If the pattern calls for ten yards around the bottom and you have material enough for but six, merely reduce each breadth proportionately and cut the skirt to fit your materials.32

Magazines and pattern companies promoted interpretations of pattern designs. An article in a 1915 Woman's Home Companion entitled "Four Ways of Wearing One Skirt" showed four decidedly different outfits obtained using the same skirt pattern by varying details, fabric, and trim. Not only did the author acknowledge that such cleverness was a way to save money, she encouraged the idea that sewing was aesthetically satisfying, telling the reader to "select the development that pleases you."33

Magazines and pattern companies promoted interpretations of pattern designs. An article in a 1915 Woman's Home Companion entitled "Four Ways of Wearing One Skirt" showed four decidedly different outfits obtained using the same skirt pattern by varying details, fabric, and trim. Not only did the author acknowledge that such cleverness was a way to save money, she encouraged the idea that sewing was aesthetically satisfying, telling the reader to "select the development that pleases you."33

The emphasis on the creative joy of sewing only increased during the 1910s and 1920s as manufacturers and retailers realized they were fighting an uphill battle with ready-made clothing. Industries with an interest in home sewing stressed the fact that by making her own clothing at home and shunning what they portrayed as generic ready-made garments, a woman could dress with more individuality. Several magazines that promoted sewing also sold patterns and were therefore eager to see readers choose to sew. One article gushed about the freedom accorded by the latest styles of the twenties:

You are permitted to do as you please. The styles we have with us this spring are an open solicitation. To go in for round necks and square necks, V and straight-across necks. And a hundred and one other variations in curves and angles, widths and breadths and dimensions generally.34

An internal Butterick document written in 1929 conceded, with some bitterness, that ready-to wear clothing had its appeal and associated it with another mass-produced product: "It has been made possible for the woman with a flapper figure to clothe herself quickly, conveniently, and inexpensively in a ‘Ford' outfit." However, the writer was convinced that off-the-rack clothing would never satisfy a truly discerning customer, insisting that "if she desires something individual, something that has not been taken off of a rack, and acquired at a price which is probably known to her social intimates, she uses piece goods and a pattern."35

Edna Maine Spooner's wedding dress, made in 1916 according to a Butterick pattern, offers an excellent example of how women adapted commercial designs. The pattern envelope explained that the style could be made with a "Slightly Raised Waistline: consisting of a Waist, In High or Lower Round Neck, with Elbow or Shorter Sleeves: and an Attached Tucked Straight Skirt, with or without the shirrings." Spooner chose the high-neck option, but gave her dress wrist-length sleeves, decorated the skirt with ribbons instead of tucks, and included gathered sleeves, a satin sash, and a detachable train – none of which were suggested by Butterick. She used the pattern for guidance but was confident enough to branch out on her own to create the dress she wanted. That she saved the pattern along with the dress and a family member donated the dress, pattern, and photograph to a university collection is an indication of the pleasure and pride she took in making the dress herself.36

Personal taste and a sense of adventure in styling were popular reasons for sewing at home, but other women had more practical reasons for creating particular styles. If their body was different than the commercial norm – if they were, for example, petite, Rubensesque, tall, pregnant, or had physical limitations – many women found that sewing was the easiest way to suit their shape. Butterick's 1911 guidebook offered a chapter on "The Best Method of Altering Patterns" with directions for adapting the designs for women with "long or short waisted figures," "extra large or small bust," "round-shouldered or over-erect figures," etc.37 Other advice warned that "commercial patterns are cut according to model measurements, but as very few women have model figures, the patterns require alteration to meet individual needs."38 Since many ready-to-wear clothes were made according to those same "model measurements" (how little has changed!), they required work and possible expense to alter. Perhaps the reality of their body shapes drove nearly 65 percent of women in the Home Economics Bureau survey to claim they made clothing because "homemade garments more nearly met individual needs."39

^topMaking Over

Another way sewing could be used to serve individual needs was to renovate older garments. "Making over" clothing had a variety of connotations, ranging from simply changing details to taking a garment apart and using the fabric to make an entirely new item. This was not always a pleasurable activity and was often more work than making a new garment, but making something over was also a test of creative and technical skills that allowed women to re-use fabrics to their advantage. Women might update the trim or sleeves on a dress, re-cut a worn-out adult's coat for a child or use material from an out-of-date dress to fashion a new skirt.

Remodeling hand-me-downs was a common way for families to stretch a clothing budget, but this practice was hardly limited to the poorest households. Nine out of ten letters to the long-running "What To Wear and How To Make It" column of the Ladies' Home Journal concerned such projects. 40 Dinah Sturgis, editor of the column during the 1880s and '90s, once instructed a "Mother" in "Springfield" to cut up her silk dress to make a new waist. "Mother" was most likely from a relatively affluent family, since few working women would have a dress of such desirable fabric.41 Blanche Ellis took fabric from an "old brown dress" and "made it into a petticoat." Another entry reads, "been making over my red dress."42 Years later, a young Mount Holyoke student received a note from her mother asking, "Can you use, or would you like to have my velvet coat? Otherwise, since I have the fur one I thought I might have the coat made into a peplum waist for the velvet skirt."43 Her mother could afford to pay someone to do the work, but she still wanted to re-use the valuable velvet.

Edith Kurtz | Read transcript Making over garments was even more of a challenge than sewing from new materials. Marjorie Durand recalled that "to re-make things is extremely difficult."44 One sewing guidebook agreed:

There is no doubt about the fact that it takes more brain power to produce a successful make-over than it does to make a lovely gown from sumptuous new material, for the pieces of material to be made over have certain set limits beyond which we may not go, while new material stretches out yard upon yard to lure the scissors.45

In making over a garment the home seamstress was limited in the amount, shape, condition, and type of fabric with which she had to work. One had to pick apart seams, press the pieces, and figure out how to combine odd shapes and different fabrics. An article describing the 1910 Paris fashions took into account that many readers would be renovating older dresses and focused on styles that combined different textures so readers could make them out of remnants:

Many of the new French frocks which I saw were indeed beautiful pictures, but they offered but little to the woman of average means, who wanted to study their good points with the idea of using them in renovating her own gowns…. The fetching little dress illustrated in picture 2 combines chiffon and serge in a most effective way. This dress also has many ideas which will be useful to the woman who is making over her last year's frock.46

A great deal of effort could be poured into a reworked garment, with disappointing results. Margaret Motter Miller received a letter from her mother describing a dress she'd worked on for her:

Well, I got your parcel post box off yesterday, & hope it reaches you safely with its darned contents. Now that's literal as well as figurative, for I put such lots of sewing on those things, & yet it doesn't show a bit or seem in the least worth it. The blue silk is still an utter mess, & look out where you put on the old pink not to stick your blessed arms through those straps I've got across the front, & so tear it all out again.47

Others had more success with remodeling projects. Lilla Viles-Wyman commented, "I have an idea for making over duck skirts that have shrunk in the laundering" and updated her dresses to suit the latest fashions by changing details such as sleeves. She wrote, "I staid [sic] at home & shifted a ruffle on my white lawn dress waist. Last year it was a ‘hip ruffle' this year it is ‘transferred' into a bertha ruffle."48 Edith Kurtz had an entire wardrobe of made-over garments when she went to college in the 1920s.

Others had more success with remodeling projects. Lilla Viles-Wyman commented, "I have an idea for making over duck skirts that have shrunk in the laundering" and updated her dresses to suit the latest fashions by changing details such as sleeves. She wrote, "I staid [sic] at home & shifted a ruffle on my white lawn dress waist. Last year it was a ‘hip ruffle' this year it is ‘transferred' into a bertha ruffle."48 Edith Kurtz had an entire wardrobe of made-over garments when she went to college in the 1920s. Kurtz recalled of her mother "she was quite skillful at making things over to make me feel that they were something new and different." 49Winifred Byrd recalled making herself a two-piece dress for her ninth-grade graduation. She knew that the other girls would be well dressed, but she could not afford anything new, so she used some turquoise taffeta from a donated dress and combined it with a black velvet top and remembered being very pleased with the result.50

Kurtz recalled of her mother "she was quite skillful at making things over to make me feel that they were something new and different." 49Winifred Byrd recalled making herself a two-piece dress for her ninth-grade graduation. She knew that the other girls would be well dressed, but she could not afford anything new, so she used some turquoise taffeta from a donated dress and combined it with a black velvet top and remembered being very pleased with the result.50

Challenging and Asserting Respectability

The freedom to make choices about how to make up a garment, renovate an old dress, or suit particular bodies went beyond creativity and practicality. This flexibility gave women a means of defining their own standards of modest or fashionable or appropriate dress. A description of an 1886 Butterick pattern noted that a woman could determine the dress's particular use by choosing the fabric and other details. It explained, "For evening and day wear the costume is equally handsome and appropriate, the materials and color selected for its development determining its suitability to any occasion."51

The understanding and implications of "suitable" clothing cannot be over-emphasized. When the Spelman dress code required that skirts not "be too short or too narrow, and necks to be high enough to avoid any appearance of immodesty," it was reiterating what the African American students already knew: the style of their garments was interpreted as a sign of their character.52 Photographs from the late nineteenth century show Spelman students wearing those decades' de rigueur corseted, high-necked, long-sleeved, and bustled dresses.53 The women pictured may not have made all of their clothes, but it is likely that they made at least some elements of their pictured outfits. By choosing factors such as collars, sleeves, skirt dimensions, and trim, home dressmakers took control of a small but important element of how they were perceived.

The understanding and implications of "suitable" clothing cannot be over-emphasized. When the Spelman dress code required that skirts not "be too short or too narrow, and necks to be high enough to avoid any appearance of immodesty," it was reiterating what the African American students already knew: the style of their garments was interpreted as a sign of their character.52 Photographs from the late nineteenth century show Spelman students wearing those decades' de rigueur corseted, high-necked, long-sleeved, and bustled dresses.53 The women pictured may not have made all of their clothes, but it is likely that they made at least some elements of their pictured outfits. By choosing factors such as collars, sleeves, skirt dimensions, and trim, home dressmakers took control of a small but important element of how they were perceived.

In the interest of sales and reputation, no commercial pattern company would suggest immodest styles, but there was a range of what people thought of as acceptable coverage at any time. In 1900, whether to make short or long sleeves or a high collar versus a lower one was a decision with real consequences. In 1908 some New York City schoolgirls were told they could no longer wear "waists with short sleeves."54 A few years later, Margaret Motter Miller's father, a strict man in general, wrote to tell her how much he disapproved of lower necklines:

Do you remember a girl by the name of Hoke, who was confirmed with your class, last Easter? She died on Thursday, I think on her way to school, of congestion of the lungs. I speak of it as a warning against the silly and dangerous fashion of having the neck and chest exposed as much in winter as in summer. 55

Dr. Miller couched his concern in terms of health, but judging by his other letters, he most likely thought lower necklines to be immodest as well. He was surely horrified only a few years later when post-World War I fashions allowed for shorter hemlines and magazine articles claimed sleeves were entirely optional. People took details such as collar height or skirt length seriously, so the ability to choose costume details mattered.

The choice of fabric was also an issue. Softer fabrics would drape differently, revealing more of a woman's shape and movement than a stiffer weave. The "peek-a-boo" shirtwaists outlawed by Horace Mann High School in 1908 were most likely shocking because of their net or lace inserts; hardly revealing by today's standards, they still attracted enough attention to be banned by school authorities and noted in the New York Times.56 By changing elements of a garment, women negotiated a degree of space within codes of dress and self-presentation.

^topMasking – or Highlighting – Ethnic and Class Distinctions

Florence Epstein Excerpt #1 | Read transcript Women adapted styles to fit their definition of modesty but also made decisions about their appearance that related to their social class. As demonstrated in the previous chapter, garment-industry operatives used their work skills to create attractive outfits, essentially masking their poverty. Photographs show that while they struggled to clothe themselves on low wages, many wage-earning women managed to dress well.

For some of these women, however, it was not enough to pass for someone who did not have to work hard for a living. Many wanted to stand out as fashionable dressers. A writer for the Yiddishes Tageblatt argued that not only were working women stylish, they were trendsetters:

The very latest style of hat, or cloak, or gown, is just as likely to be worn on Grand Street as on Fifth Avenue. The great middle class does not put on the newest styles until they have been thoroughly exploited by Madam Millionaire of Fifth Avenue and Miss Operator of Essex Street.57

The versions worn by factory operators were surely made of cheaper material and most likely were too flashy for many middle-class observers. Kathy Peiss points out that many working women chose especially ornate fashions, sometimes displaying "aristocratic pretensions," although

working women's identification with the rich seems to have been more playful and mediated than direct and calculated, as much as commentary on the rigors of working-class life as a plan for the future. Significantly, women did not imitate haute couture directly, but adapted and transformed such fashion in creating their own style.58

Nan Enstad writes of the same flamboyance that working women were challenging the dominant meaning of "ladyhood," creating their own distinctive style that implicitly denied that labor made them masculine, degraded, or alien."59 Style was a way to assert that you deserved notice. Sixteen- year-old Sadie Frowne, a garment worker, claimed that "a girl who does not dress well is stuck in a corner, even if she is pretty." 60 Plainly dressed Sara Smolinsky, the ambitious working-class protagonist of Bread Givers, is scolded by her sister who tells her, "You don't dress like a person."61 Glamour and fashion helped women claim identity and importance in a society that viewed wage earning women as unfeminine.

These "flashy" young women were criticized by some in the middle class who believed a sober appearance was more in keeping with upward mobility. Indeed, when Bread Givers' Sara achieves her goal of attending college, she notices the "plain beautifulness" of the other students' clothing in comparison to the "cheap fancy style" of the Lower East Side.62 What those observers missed, however, was that money and time spent on fashion was a response to a life of work and financial constraint. In an article explaining the shirtwaist strike of 1909, Clara Lemlich argued, "We're human, all of us girls, and we're young. We like new hats as well as any other young women. Why shouldn't we?"63 The same sewing skills that allowed these women to earn a living, dress appropriately for their jobs, dress like an "American," or hide their family's economic troubles also gave them a tool to express their own sense of beauty and glamour.

While some women sewed in order to assert differences, others did so to demonstrate that they fit in. As demonstrated in the Spelman College example, African American women often sewed in order to conform to – or surpass – standards that the more affluent believed to be beyond their economic and moral capabilities. This was an uphill battle. For example, an 1899 article in the New York Times described a study by W. E. B. Du Bois of the living conditions of African American families. The study claimed, among many other things, that rural African Americans dressed poorly relative to their urban counterparts. It also noted that only a few rural households were in possession of sewing machines, and those machines "were not yet paid for." Du Bois was interested in documenting problems with the goal of "racial uplift," but the mainstream white press took his observations of poverty and included the line "Much Depravity is Found" in the headline.64

In this environment, dressing well was a political act. Textile scholar Patricia Hunt writes, "Adoption of current fashions in their dress was one way in which some African American women both asserted their affluence and assimilated into mainstream American society."65 Kathleen Adams, a teacher who grew up in a middle-class household, recalled the fashionable Sunday morning scene on Atlanta's Auburn Avenue with the churchgoers dressed in quality fabrics and stylish designs.66 Many photographs of African Americans show them wearing the same styles as touted in the women's magazines aimed at a middle-class white audience. In one image, Leah Pitts of Jones County, Georgia wears a shirtwaist and long skirt trimmed with ribbon; most likely she made both pieces as she enjoyed a reputation as a seamstress despite her blindness.

In this environment, dressing well was a political act. Textile scholar Patricia Hunt writes, "Adoption of current fashions in their dress was one way in which some African American women both asserted their affluence and assimilated into mainstream American society."65 Kathleen Adams, a teacher who grew up in a middle-class household, recalled the fashionable Sunday morning scene on Atlanta's Auburn Avenue with the churchgoers dressed in quality fabrics and stylish designs.66 Many photographs of African Americans show them wearing the same styles as touted in the women's magazines aimed at a middle-class white audience. In one image, Leah Pitts of Jones County, Georgia wears a shirtwaist and long skirt trimmed with ribbon; most likely she made both pieces as she enjoyed a reputation as a seamstress despite her blindness.  Another photograph,

taken at about the same time, shows the members of the Cairo, Georgia Mothers' Club sitting on a porch. The women are all dressed in stylish dresses or shirtwaists and skirts; as community-oriented clubwomen, they would have been heavily invested in dressing well. Home sewing helped these women match or even surpass white standards of propriety.

Another photograph,

taken at about the same time, shows the members of the Cairo, Georgia Mothers' Club sitting on a porch. The women are all dressed in stylish dresses or shirtwaists and skirts; as community-oriented clubwomen, they would have been heavily invested in dressing well. Home sewing helped these women match or even surpass white standards of propriety.

However, not all African Americans conformed to white fashions. Many made cloths with which to cover their hair in a distinct ethnic style. As Hunt explains, many African American women, out of economic necessity or choice, "participated in aesthetic and artistic expression that had nothing to do with following the latest fashion. Their artistry is particularly evident in their headcloths."67 The kerchiefs were often made of bright and patterned fabric. A photograph of a woman from Thomas County, Georgia shows her wearing a paisley headcloth.68 These kerchiefs were practical. They served the utilitarian purpose of keeping hair neat and protecting skin from the hot sun, they were less expensive than formal hats, and they could be worn during agricultural and domestic labor. In addition to their practical uses, headcloths were decorative links to African and slave practices. Making and wearing headcloths was a way for women to use sewing skills to accommodate practical needs while dressing according to their own style.

However, not all African Americans conformed to white fashions. Many made cloths with which to cover their hair in a distinct ethnic style. As Hunt explains, many African American women, out of economic necessity or choice, "participated in aesthetic and artistic expression that had nothing to do with following the latest fashion. Their artistry is particularly evident in their headcloths."67 The kerchiefs were often made of bright and patterned fabric. A photograph of a woman from Thomas County, Georgia shows her wearing a paisley headcloth.68 These kerchiefs were practical. They served the utilitarian purpose of keeping hair neat and protecting skin from the hot sun, they were less expensive than formal hats, and they could be worn during agricultural and domestic labor. In addition to their practical uses, headcloths were decorative links to African and slave practices. Making and wearing headcloths was a way for women to use sewing skills to accommodate practical needs while dressing according to their own style.

Conclusion

During the late nineteenth century, most women sewed out of necessity and custom, but as other options competed with home sewing, the reasons why women sewed became more complex. Family dynamics, free time, sewing skills, cultural priorities, rural isolation, and community pressures all affected who chose to sew clothing at home. First and foremost was economics: sewing was almost always cheaper than buying clothing. Yet home dressmaking was also a source of personal pride, a symbol of motherly love and wifely duty, and a way to have greater control over physical appearances. Sewing was a sea of contradictions and understandings of women's work and roles. The same skills that aimed to create an ideal housekeeper, wife, and mother also promised sexual attraction and artistic satisfaction, masked class difference, and allowed for personal interpretations of modesty and style.

As a form of labor that adapted easily to changing traditions, sewing was unlike much wage work. Women had a great deal of control over the process. Home dressmakers enjoyed a choice of materials, designs, and methods. To a certain extent, they could control the amount of time they spent on a particular job and when they did the work. They struggled to match varying degrees of skill to demanding styles, tastes, and outside pressure. However, many home dressmakers were rewarded for their efforts with significant cash savings, pleasure in the process itself, approbation from family and neighbors who associated sewing with appropriate domestic priorities, and a product that allowed a degree of self-expression. As the authors of the Bureau of Home Economics study noted:

A fact which should not be overlooked is that many women admitted they sewed at home because they enjoyed it. One of the best avenues and often the only one which women have for expressing and developing their creative ability is in making their own clothing or that of their family. No doubt women of the future will continue to exercise this ability because they find it a joy and satisfaction.69

While understood as a staple of domestic labor, home sewing could also provide an outlet for personal tastes and pleasures. Moreover, it could serve as a tool for challenging some of the prejudices against women who were so often judged by their appearance. In this way, women could take a skill that for many represented limitation and hard work and make it a tool for expressing individuality and opening doors.

It took time and effort to sew well enough to use it as this kind of tool. Sewing was a lifetime skill that was often learned early and girls learned practical skills along with their accompanying cultural connotations. Girls were therefore taught not only how to sew, but why – and that "why" depended greatly upon who they were and the lives they would supposedly lead as adults. The following chapter will explore the multiple dimensions of sewing education and its cultural ramifications.

^top