| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| However, after it became clear that my broad questions about women's "way of life long ago" were failing to elicit enthusiastic responses, I tried a more direct approach one afternoon when Juliana hobbled over to join Rosalina and me as we sat outside Rosalina's hut near the end of our third interview. Inspired by her larger audience, Rosalina began to reminisce about the maternal grandfather who had been one of "Ngungunyana's heroes" and to describe the special military headdresses and ocher-stiffened hairstyles that elite Nguni men and women used to wear. Seeing my chance, I commented that I had read in books that women long ago had also marked their skin. At that, Rosalina interrupted me excitedly to ask (in Portuguese) if I was referring to tatuagens (tattoos). When I said I was, she began to recount how her mother and maternal grandmother had indeed "gone around cutting their bellies" to "make them beautiful." Rosalina denied having done this herself—"Hah!," she scoffed, "I'm of now. . . ." But when Juliana (who knew little Portuguese) realized what we were discussing, she spoke up suddenly in Shangaan—"Tinhlanga [tattoos]? Tattoos? You're talking about tattoos?"—and then, with a self-conscious laugh, she promptly stole the spotlight from the warrior's granddaughter: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the lively exchange that followed, as Juliana struggled mightily to express herself in words I could understand, Rosalina was able to reassert her history-telling authority both by assuming the role of translator and by augmenting Juliana's stories with a deliberately more detailed account of how women had tattooed one another "long ago." Clearly surprised at my interest, Rosalina seemed just as eager as Juliana to speak on this subject. However, it was not until our sixth interview, more than five months later, that Rosalina mentioned tattoos again. This time it was to tell me that she had in fact had tinhlanga done, albeit under circumstances rather different from those experienced by other women her age (see below). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Such untruthfulness—or, at least, wariness—on the question of tattooing was not peculiar to Rosalina. In our first interview with Valentina Chauke, three weeks after that revealing session with my neighbors, I asked whether she had done anything to "make herself beautiful" when she was a girl. Valentina's negative "Mm-mm!" was as firm as Rosalina's initial denial, and Valentina was not shaken even slightly when Aida pointed to the faint scars on the elderly woman's arms and demanded, "What are those?" "That wasn't me," Valentina retorted. "That was Ntete, the daughter of Nyanga. She brought these things back here from that prostitution of hers." "These things"—VALENTINA tattooed on her right forearm, CHAUKE on her left—were all she would admit to that day, despite Aida's persistent teasing of Valentina through the rest of the interview with the repetition of the question "You didn't cut tinhlanga?" 3 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It was Valentina's daughter Talita who betrayed her, when we went to interview Talita that same afternoon. Asked about "making herself beautiful" when she was young, Talita responded first, hesitantly, with "We were poor. I couldn't buy dresses." But when Aida prodded her by remarking, "No, she wants to know, maybe you cut tinhlanga, maybe you wrote something—," Talita shrieked with delight and laughed until tears rolled down her face. "Hee!! Hee!! Truly! I wrote on myself! I cut tattoos!" When we were saying our good-byes over two hours later, after what was certainly our most boisterous (and sexually explicit) interview to date, Talita commented that it was "not good to hide those things that were customs, long ago," a remark that prompted Aida to ask Talita about her mother's testimony that morning. Valentina, Talita assured us, had more tattoos than she had let on, and we should not be "afraid" to ask her about it again. 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Talita's determination that I should know about tinhlanga went considerably further than this, as Aida and I discovered over the next couple of days. During interviews with two of Talita's neighbors, Aldina Masangu and Lise Nsumbane, the subject of tattooing arose the moment the words "long ago" were out of my mouth. Not only that, but each woman promptly hoisted her skirt (a rare sight, since women are not traditionally supposed to bare their legs in public) to show us the decorative marks etched on her thighs. 5 My suspicion that someone was spreading the word in Facazisse was confirmed over the following weeks, as Aida, Ruti, and I suddenly began to receive visits from elderly women who said they too wanted to talk to the "little mulungu." One particularly assertive xikoxana, Katarina Matuka, demonstrated her qualifications in no uncertain terms one late July afternoon when she caught up with me on the footpath near her home. To my astonishment, before we had even exchanged greetings, Katarina yanked up her red turtleneck to display the array of scars on her stomach and chest. She chuckled mischievously as I stammered my compliments and (sure I had committed some terrible offense) thanked her awkwardly and hurried on my way. 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I later learned that Katarina was notorious for such exhibitions, but her behavior was not as extraordinary as I then believed. With each woman we subsequently interviewed about tattooing, within Facazisse and then elsewhere in the district, Katarina's performance seemed less and less strange and my own inhibitions plainly out of place. More times than I can count, my simply saying the word tinhlanga was enough to send a woman into gales of laughter, and, more often than not, my request that an interviewee use pencil and paper to draw her tattoos was met with a snorting headshake and the removal or rearrangement of clothing to expose her tattoos instead. I had to politely decline Lucia Ntumbo's offer to pose half undressed while I photographed her tattoos, an act I was sure would offend Antioka church folk (who would certainly hear about it) and that I doubted I could justify even to myself. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There was something about body-marking, in other words, that either raised or dissolved boundaries of translation and of mistrust in women's willingness to share memories of past experience with me. Partly, I think, women were having fun with us, enjoying their ability to shock the mulungu with candid accounts of how and with what effects—sexual effects, above all—tattooing had been done. More importantly, though, once elderly women felt comfortable narrating their knowledge of long ago through, and as, stories about tattooing, they behaved as though we had crossed a watershed of some kind. Less taboo a topic than labia elongation, 7 tinhlanga were nonetheless even more powerful symbols of a history women understood as theirs alone—a gendered construction of a past they remembered and controlled themselves. As this chapter explains, their attitude stems to some extent from the transformation of female body-marking into a site of racialized struggle during the colonial period, when European (and European-trained African) missionaries and schoolteachers raised the stakes of women's tattooing by redefining it as an act of resistance against the "civilizing" influences of colonial culture. Yet long before tinhlanga became a gendered battleground between white and black ways, between xilunguand xilandin,women were "writing" on their bodies—as they had written on their clay pots—for reasons of their own. Signs, on the one hand, of women's efforts to negotiate the frontiers of their social universe and, on the other hand, of the informal networks of affiliation through which they had mediated normative, androcentric structures of community and authority, tinhlanga told histories that women could not, or would not, always voice. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As in the song lyrics quoted at the head of this chapter, among the women I interviewed in Magude tattoos asserted the truth of remembered experience when the credibility of speech might have been in doubt, or where there were limits to what women were permitted to put into words. In a context where official notions of history, indigenous and foreign, claim authority over the past through disembodied ("objective") constructions of "what happened," truth-claims inscribed permanently on the body can be perceived as quite subversive. Where women's bodies in particular have served as a key terrain in masculine contests for political and cultural hegemony, the power of tattooed tales as feminine historical knowledge is especially dangerous, most of all when women's tinhlanga refuse to tell the stories expected of them—when under the pressures of intensifying economic hardship and social differentiation set in motion by imperialisms of various forms, tattoos have offered an idiom for women to claim ever wider grounds of community and identity for themselves. If this power felt tenuous in postwar Magude, with the much reduced incidence of tattooing since the onset of the Renamo war, few interviewees depicted its waning as more than a temporary setback. Indeed, the relish with which so many of them flaunted their faded tattoos suggests that the truths of their tinhlanga remain as real, and as necessary, as they were on that "long ago" day when the cuts were made.

| 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The earliest evidence of scarification from southeast Africa is recorded not in written documents but in clay, on the faces of the famous terracotta Lydenburg Heads, which were unearthed by archaeologists in the eastern Transvaal in 1962.  Dated to the early sixth century A.D. and tentatively associated with initiation ceremonies, the faces bear incised molded strips of clay running in a vertical line, from the upper mid-forehead to the tip of the nose, and in two horizontal lines from the outer corner of each eyebrow to each ear. 8 The first written reference to tattooing in southern Mozambique occurs in an account by William White, a British merchant who visited the busy international port of Delagoa Bay in 1798. Wedged between a long paragraph on hairdressing and a discussion of polygamy, we find the following brief comment on practices of body-marking among local men and women: Dated to the early sixth century A.D. and tentatively associated with initiation ceremonies, the faces bear incised molded strips of clay running in a vertical line, from the upper mid-forehead to the tip of the nose, and in two horizontal lines from the outer corner of each eyebrow to each ear. 8 The first written reference to tattooing in southern Mozambique occurs in an account by William White, a British merchant who visited the busy international port of Delagoa Bay in 1798. Wedged between a long paragraph on hairdressing and a discussion of polygamy, we find the following brief comment on practices of body-marking among local men and women: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the early nineteenth century, reports from European and African traders noted the appearance of travelers with scarred faces and chests, whom historians have identified as proto-"Tsonga," as far afield as the headwaters of the Limpopo River to the north and the area of the present-day Transkei to the south. 10 The correlation of particular decorative markings with the people who would later be called Tsonga hardened from the 1840s on, when João Albasini was joined at his military stronghold in the northern Transvaal by refugees from east of the Lebombo hills who bore, on their noses and cheeks, lines of large keloid scars—described variously as knobs, lumps, warts, and buttons—which earned them the epithet Knobneuzen (Knobnose) from Boer residents of the Zoutpansberg. 11 In the early nineteenth century, reports from European and African traders noted the appearance of travelers with scarred faces and chests, whom historians have identified as proto-"Tsonga," as far afield as the headwaters of the Limpopo River to the north and the area of the present-day Transkei to the south. 10 The correlation of particular decorative markings with the people who would later be called Tsonga hardened from the 1840s on, when João Albasini was joined at his military stronghold in the northern Transvaal by refugees from east of the Lebombo hills who bore, on their noses and cheeks, lines of large keloid scars—described variously as knobs, lumps, warts, and buttons—which earned them the epithet Knobneuzen (Knobnose) from Boer residents of the Zoutpansberg. 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Around the same time, European writings from southern Mozambique began increasingly to include descriptions of "native" practices of body alteration and adornment, from scarification to teeth-filing, lip-piercing, eyebrow-shaving, hairstyling, jewelry, and dress. Reading tattoos in particular as a "marker of the primitive," 12 imperial observers debated about the ways in which differences in dress and ornamentation among Africans—cloth versus skin, beads versus bone—reflected a "tribe's" position on the savagery-civilization continuum, and their writings implicitly ranked tribal groups according to imputed powers of cultural resilience. In these discussions, the "Tsonga" appear—principally by virtue of their scarification practices—to have infinitely plastic (hence, in imperial eyes, innately weak) cultural and political identities. According to Junod, the custom of decorating the face with keloid scars had "ancient" roots among the earliest inhabitants of the coastal lowlands south of the Save River. When, Junod reported, proto-Tsonga groups invaded the area in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, their subjects ridiculed the "flat noses" of their conquerors so relentlessly that the Tsonga were forced to adopt the practice themselves. 13 With the Nguni invasions of the early nineteenth century, facial scarification assumed heightened political significance when (again according to Junod) Zulu impis sent by Shaka in pursuit of the rebel leader Soshangane sought out Nguni targets between the Nkomati and Olifants Rivers by looking for men who had no "buttons on their face." While the mortal danger temporarily associated with smooth noses caused "many [Nguni soldiers] to submit to the operation," the trend apparently reversed itself the moment the threat had passed, and "knob" facial scars once again became, to the Nguni ruling class, a scorned sign of cultural inferiority among subject peoples. 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By the 1860s and 1870s, when St. Vincent Erskine and Frederick Elton were crisscrossing the lands between the Drakensberg Mountains and the coast, knobnose tattooing appeared to be on the way out, supplanted by the style of ear-piercing popular among the Nguni. 15 As Europeans saw it, this transformation in habits of body-marking signaled an irreversible cultural as well as political surrender, a wholesale acceptance of assimilation into the hegemonic social order of a conquering tribe. St. Vincent Erskine summed up the prevailing view when he wrote, after his first sighting of "Knob-nosed Caffres" northeast of Origstadt in 1868, that "These people, as a tribe, are extinct, having amalgamated with the tribes of Manjaje and Umzeila. . . . In a few years knob-noses will be as extinct as pig-tails." 16 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Amalgamation" with respect to tattooing, however, was a visibly gendered process, as European sources from Erskine on carefully noted. Not only did "Tsonga" women generally decorate their skins more elaborately than did their menfolk (the women, according to Junod, being "more desirous still of personal adornment" 17). They also continued marking their bodies long after men had adopted Nguni, and then European, fashions of dress and ornamentation. Whereas the men encountered near Origstadt, for instance, had small knobs down their forehead to the tip of their nose, women wore additional markings across their cheekbones and along their upper lip. 18 When Frederick Elton traveled overland from the Oliphants River to Lourenço Marques in 1870, crossing the Nkomati and chief Magudzu's territory en route, he observed that "Nearly all of the [Amatonga] women disfigure themselves by tattooing a double line of warts across the forehead, joined by a curved line on either cheek, and occasionally a double or even triple row of lumps and stars across the upper part of the bosom, or an elaborate pattern on the abdomen." Only "some few [Amatonga] men," meanwhile, were still "adopt[ing] the peculiar ornament of 'knob-nuizen.'" 19 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By the turn of the century, Junod could write that Knobneusen was no longer even an appropriate name for the Transvaal Tsonga because "pimple" tattooing had ceased to be practiced in that area, although the scarification of women's chests and "waists" was still widespread. 20 By the early twentieth century, when Junod and Earthy were publishing their ethnographic studies of the Tsonga and Lenge, 21 ear-piercing appeared to be the only form of body-marking extant among men, while women across southern Mozambique were still tattooing themselves with "a bewildering variety" of incised and keloid scars on their shoulders, stomach, and abdomen. 22 Convinced that what they regarded as a primitive and degrading tribal practice was bound to vanish as women were exposed to civilization and the "evolution of costume," missionary ethnographers still had trouble explaining why women's tattoos did not neatly conform to ascribed clan or (putative) ethnic identities and why even in the 1920s and 1930s new female tattoo styles seemed to be emerging. Junod declared that, even if the practice lingered, the once "deep" ritual meanings of women's body-markings had "more or less disappeared," reducing them to little more than "ornamental mutilations" probably connected to adolescence or marriage. 23 Earthy's more thorough quest to uncover a primal religious meaning for the tattoos of Lenge women led her to the similarly disappointing conclusion that, at most, they contained faint "vestiges of totemism" already weakened by the influence of plain-skinned European fashion. 24 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In their effort to document tribal custom before it disappeared, both Junod and Earthy left revealing clues to the complex significance of tinhlanga  for women during the early decades of Portuguese colonial rule. Earthy's detailed descriptions of body-marking in particular recall, and shed gendered light on, William White's observations from circa 1800, especially the tension in White's account between his recognition of the uniqueness of every individual's set of tattoo marks and his belief—rooted, perhaps, for women during the early decades of Portuguese colonial rule. Earthy's detailed descriptions of body-marking in particular recall, and shed gendered light on, William White's observations from circa 1800, especially the tension in White's account between his recognition of the uniqueness of every individual's set of tattoo marks and his belief—rooted, perhaps,  in the only categories he was able to imagine—that patterns in tattooing were best understood as "family" resemblances. Junod, for instance, contrasted the epigastric tinhlanga of two young women belonging to the Nkuna clan in Shiluvane (Transvaal) in 1900 with those of two young Tembe clanswomen from a rural village outside Lourenço Marques in 1926. Although the tinhlanga are not identical in either pair, they are sufficiently similar—and sufficiently different, as pairs, from one another—to convince Junod (like White, mapping indigenous social organization in the only way he knew) that women's tattoos varied "according to clans," discrepancies of time and place not even entering his discussion. 25 in the only categories he was able to imagine—that patterns in tattooing were best understood as "family" resemblances. Junod, for instance, contrasted the epigastric tinhlanga of two young women belonging to the Nkuna clan in Shiluvane (Transvaal) in 1900 with those of two young Tembe clanswomen from a rural village outside Lourenço Marques in 1926. Although the tinhlanga are not identical in either pair, they are sufficiently similar—and sufficiently different, as pairs, from one another—to convince Junod (like White, mapping indigenous social organization in the only way he knew) that women's tattoos varied "according to clans," discrepancies of time and place not even entering his discussion. 25 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Although Earthy similarly claimed to be able to "tell a Lenge or Tsopi woman at a glance" from her tattoos, 26 she was more attentive to the enormous  diversity of women's body-marking and to the many ways in which tinhlanga defied classification along strictly ethnic, clan, or family lines. Earthy in her account presents a list of a truly "bewildering" range of tattoo types, designs, and meanings prevalent among Chopi and Lenge women in the 1920s: keloid and incised tattoos of various sizes; images symbolizing seashells, birds, insects, reptiles, plants, arrowheads, body fluids (saliva, tears), lunar and astral bodies, mortar and pestle, a "sacred wand" used in women's harvest ceremonies, and more abstract designs representing such social concerns as marital status, mourning, and protection from witchcraft. diversity of women's body-marking and to the many ways in which tinhlanga defied classification along strictly ethnic, clan, or family lines. Earthy in her account presents a list of a truly "bewildering" range of tattoo types, designs, and meanings prevalent among Chopi and Lenge women in the 1920s: keloid and incised tattoos of various sizes; images symbolizing seashells, birds, insects, reptiles, plants, arrowheads, body fluids (saliva, tears), lunar and astral bodies, mortar and pestle, a "sacred wand" used in women's harvest ceremonies, and more abstract designs representing such social concerns as marital status, mourning, and protection from witchcraft. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moreover, the responses Earthy's informants gave when asked why they "disfigured" their bodies in this manner suggest an explanation quite different from what ethnographers may originally have had in mind. Most women, Earthy reported, told her they tattooed themselves to "do honour to their bodies, to make them beautiful"; to enhance marriage prospects; to demonstrate "physical courage and endurance"; and to avoid being ridiculed as a "fish" for having a smooth belly. One woman, though, answered more philosophically: | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It was this eloquent comment that led Earthy to characterize female body-marking as "the story of [women's] lives written on their own flesh." While not necessarily ruling out the possibility that tinhlanga were somehow related to ethnic or family associations, this reading of tattoos as site and sign of historical memory—another form of women's knowledge of the past—suggests that the relational meanings of women's tinhlanga are considerably more complex than foreign commentators have guessed and may tell us a good deal more about women's histories than simply the tribe or clan to which they belong.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All told, I interviewed approximately forty women about tattoos, their own and in some instances those of their mothers or grandmothers. While the youngest members of this group were born in the mid-1930s, the majority were born before 1925. When the eldest among them (those born circa 1905-15) recalled tinhlanga they had seen on older women while they were growing up, they could provide a glimpse of female body-marking practices across the region as far back as the 1870s. 28 These practices include the physical act of "cutting tattoos"—my translation of the Shangaan phrase kutlhavela tinhlanga, where the rather violent verb kutlhavela (from kutlhava, to stab or pierce) describes the cutting and/or piercing of the skin. 29 Very few of the interviewees had ever cut tattoos for someone else, since for the most part women had had their tattoos done by individuals older than they and the incidence of tattooing in Magude had declined dramatically since the beginning of the Renamo war. Women's testimony about the individuals who gave them their tinhlanga, on the other hand, was often strikingly detailed, and in this section I also draw on these recollections to consider not only why girls and women sought to embellish their own skin but also why they were usually able to find someone to do it for them. All told, I interviewed approximately forty women about tattoos, their own and in some instances those of their mothers or grandmothers. While the youngest members of this group were born in the mid-1930s, the majority were born before 1925. When the eldest among them (those born circa 1905-15) recalled tinhlanga they had seen on older women while they were growing up, they could provide a glimpse of female body-marking practices across the region as far back as the 1870s. 28 These practices include the physical act of "cutting tattoos"—my translation of the Shangaan phrase kutlhavela tinhlanga, where the rather violent verb kutlhavela (from kutlhava, to stab or pierce) describes the cutting and/or piercing of the skin. 29 Very few of the interviewees had ever cut tattoos for someone else, since for the most part women had had their tattoos done by individuals older than they and the incidence of tattooing in Magude had declined dramatically since the beginning of the Renamo war. Women's testimony about the individuals who gave them their tinhlanga, on the other hand, was often strikingly detailed, and in this section I also draw on these recollections to consider not only why girls and women sought to embellish their own skin but also why they were usually able to find someone to do it for them. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| To an even greater extent than in the previous chapter, my methodology for exploring the historical meanings of women's tattoos combines oral history with the insights of feminist archaeologists, particularly those who have tried to tease out the less easily accessible byways of women's pasts from the tracks of social and spatial relationships embedded in feminine material culture. 30 On the one hand, I asked women to talk about their experiences of tattooing—why they did it (or why they did not do it), what the process was like, what it meant for them personally, what the most important consequences of tattooing have been. On the other hand, I sketched and questioned women about the tattoos themselves. Most of the time women volunteered to show us their tinhlanga, but occasionally they preferred to draw them for us in the sand or (in a very few cases) with pencil and paper. I realize that there are drawbacks to this approach, that they or I might have got details of tattoo design slightly wrong because I was not always able to see the tinhlanga themselves. As I hope will become clear in the remainder of this chapter, however, exact renderings of the appearance of their tattoos was not what women most wanted or were able to remember in interviews. In this respect, the methodology I developed for tracking women's tattoos explores the interface of memory and material culture instead of trying to separate one mode of historical knowledge from the other. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Significantly, while only a small number of interviewees could recall the specific Shangaan names for particular tattoo designs, every woman could narrate when, where, and with whom she had each tattoo cut, who cut it for her, with what materials and so forth. This pattern tells us a great deal about the historical meaning of tinhlanga to the women who bear them. But the tattoos themselves are not unimportant, and the historical tale they tell is the subject of the final section of this chapter. Taken together, women's stories about tattooing—and the tattooed stories written on their skin—offer a feminine vision of the past, a vision that is as much about gendered constructions of community and change as are the other forms of historical memory examined in this study. Unlike naming practices, life stories, and pottery, however, what women have done with their bodies in this region has rarely been dismissed as unimportant, whether by their menfolk or by European colonial actors. The transformation of tinhlanga into a terrain of struggle during the twentieth century intensified the emotive power of tattoo memories in postwar Magude, making them an unusually intimate window on histories of female friendship, sexuality, and everyday race and gender politics in the countryside. | 25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interviewees quickly troubled dominant ethnographic stereotypes of female tattooing. Oral testimony, and the tattoos themselves, show no strict correlation between ethnic or clan identity and body marks, either during interviewees' own lifetime or in the time of their mothers and grandmothers. While a few women remarked that only "those Chopi women" tattooed their legs, several interviewees who identified themselves as Shangaan had tinhlanga on their thighs. No one, moreover, gave ascribed social identity as the reason for her tattoos, and no two women who called themselves by the same ethnic name or who belonged to the same clan bore identical sets of tinhlanga. It would be tempting to accept the theory (implied by White and Junod) that women's tattoos were an inscription of consanguineal kinship intended as evidence—perhaps for husbands and affines—that wives' affective loyalties lay permanently with their natal clan. 31 Women, however, explained the resemblances among their tinhlanga rather differently, and virtually never did they mention husbands (or men, or affines, at all) when identifying why they had particular tattoo designs. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Women's oral accounts similarly complicate assumptions that tattooing's central purpose was to transform nubile girls into sexually desirable wives. Even though many interviewees laughingly confided that tattoos "make your husband happy" because when a man "grabs" and strokes a woman's tattooed body his penis instantly "wakes up," they clearly linked heightened male sexual interest with women's own sexual satisfaction: tinhlanga not only induced a man to spend more time caressing his wife, they also helped to ensure that he "woke up" (when, for instance, his penis rested against her textured skin) for a second or third round of intercourse. 32 Perhaps more telling, many women had their first tattoos done long before puberty and went on accumulating them throughout adulthood, in some cases even after a failed marriage had convinced them they no longer "wanted men." 33 While the desire to be attractive to men was certainly important, and other women who added to their tinhlanga later in life did so after they were widowed or divorced, partly in order to win another husband, women never portrayed their motivation for cutting tattoos as solely (or even primarily) to fulfill male sexual expectations. Indeed, women's raucous stories about husbands' gratitude and comically slavish attention to tattooed wives represent male enjoyment almost as an ancillary effect of tinhlanga; and women who were not tattooed at all, such as Cufassane Munisse, challenged us to deny that a man "needs more than that little hole" to "wake up" and enjoy intercourse. 34 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The emphasis in oral narratives on the xihundla (secrecy) surrounding the act of cutting tattoos also adds an interesting wrinkle to scholarly explanations of body-marking, in southern Mozambique and elsewhere in Africa, as simply one element of an organized series of initiation rites that adolescent girls underwent at the behest of, or under the strict supervision of, their female elders. 35 According to interviewees, tinhlanga were always done nhoveni (in the bush) or khwatini (in the woods), so that no one—"especially men and children"—would "see all that blood." 36 Groups of anywhere from two to ten girls would "invite one another" and make clandestine arrangements to visit the mutlhaveli (tattoo artist) the following day. Having prepared what they needed to take with them the previous night (e.g., a piece of old cloth to staunch the bleeding), they would set off together at dawn without telling anyone where they were going or why. Even though it was seldom possible for girls to hide their wounds when they returned home, the point was to conduct oneself with circumspection and decorum in the presence of elder women, even mothers and grandmothers. Valentina Chauke scolded me just for asking whether she informed her grandmother N'waXavela the day she had her tinhlanga done: "Hoh! Do you show those elders? You didn't talk about these things, even with your grandmothers. They know we're doing these things, but they don't say anything, and we don't say anything. We had respect!" 37 Unlike labia elongation, which the majority of interviewees described as essential to becoming a woman of "value," no one remembered tinhlanga as something senior women compelled girls to do. Female elders may have advised daughters and granddaughters to get themselves tattooed, but, as Teasse Xivuri explained, "No one forced you. Our mothers said, 'You, if you don't want tinhlanga, you don't do it. If you want them, you'll do it too.'" 38 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This insistence on the discretionary character of tattooing in the context of intergenerational relations among women reverberated through accounts of how the tinhlanga economy functioned. While most interviewees had the majority of their tattoos cut by someone older than they, and a small number had been tattooed (as girls) by a xikoxana (old woman), more often than not the mutlhaveli was a slightly older girl or a woman of their mother's age (that is, someone separated from her clientele by no more than a full generation). And while roughly one-third of the tinhlanga in the group were cut by a relative, the remainder were done by friends, neighbors, or strangers known only to girls by their tattooing reputation (e.g., for causing less pain, or producing cuts with less risk of infection). All women stressed that they went to the mutlhaveli of their choice, and a mutlhaveli who was especially skillful often had "lines of girls" requesting her services. 39 Moreover, when there was no kinship involved, girls (or women) demonstrated their appreciation to the mutlhaveli by offering her a gift of some kind: a few hours of farm work, a pot of water, a little corn, a bead bracelet, or a safety pin to "wash her eyes" because she had had to look upon so much blood. 40 In rare instances, money might be offered instead, but interviewees declared unanimously that even cash offerings were never a hakelo (payment). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If both men and senior women play marginal roles in interviewees' recollections of why they wanted tinhlanga, intragenerational pressures loom large in oral accounts. Asked why they had themselves tattooed, women's most common first response was "to make myself beautiful" or "to beautify [kuxongisa] my body." Beauty, of course, is culturally and historically specific, constituted by standards held as normative or ideal by people with some sense of shared social location and identity. Women made explicit the relational content of tattooed beauty in Magude in the comment that usually followed close on the heels of this first response: "I saw what my fellow girls had, and me, I longed for it too." As we saw in chapter 3, by "fellow girls" (vanhwanyana kulorhi or tintombi kulorhi)—or, in explanations about adult tattooing, "fellow women"—women meant other females in their age group (ntangha), with divisions determined roughly by puberty, marriage, and number of children. 41 Female fellowship, however, was also contingent on shared geographic place. In women's recollections of their youth (circa 1910-40), the horizons of shared place were at the same time fairly limited and infinitely elastic, defined principally by the ganga (subdistrict) or tiko (in this context, chieftaincy) where they resided but also by the landscape they or their peers traversed through visiting and trade and had "seen with [their] eyes." As Aldina Masangu recalled, "It's because there's traveling. 42 Well, when you travel, you go and you arrive at a place, or maybe another person arrives there. And you see those people of that land, you'll know that, there they do such-and-such. We say, 'Heh! And me, I want these things! And me, I want them.'" 43 | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The key site of spatial connection was at the river's edge, where girls and women living or visiting in the same area went to draw water, wash clothing, and bathe every day. Indeed, along with the bush and the forest, combeni (at the river) was a crucial locational setting in tattoo narratives, the place where fellow girls and women compared and judged the "beauty" of one another's tinhlanga and where tattoo-based feminine friendships were courted, negotiated, and sealed. As Albertina Tiwana explained, the cumulative pressure of these daily performances was enough to convince most girls that, however much they may have dreaded tattooing, the imperatives of friendship and the desire to belong to a cohort of fellows ultimately left them little choice: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Desire to belong to communities of female xinghana (friendship)—communities whose boundaries were marked by shared standards of tattooed beauty—did not necessarily diminish when young women moved to their vukatini (marital home), usually some distance away from where they had grown up. Indeed, exogamy and virilocal residence norms made tattooing arguably even more important for a woman after marriage,  when peer pressure from fellow girls she had known probably since birth was replaced by the discomfort of newcomer status and the need to forge affective bonds beyond the precarious circle of her in-laws. Melina Xivuri, who was born circa 1910 in Xikwembu (Phadjane) and married into the remote border area of Muqakaze (northern Moamba district), reminisced about the power of tinhlanga to lay the groundwork of friendship between women with little in common besides gender and the accidental geography of marriage. Here too, the river was a crucial site for fostering such connections, but, as Melina suggests, so were the other gendered spaces where fellow women ordinarily encountered one another: when peer pressure from fellow girls she had known probably since birth was replaced by the discomfort of newcomer status and the need to forge affective bonds beyond the precarious circle of her in-laws. Melina Xivuri, who was born circa 1910 in Xikwembu (Phadjane) and married into the remote border area of Muqakaze (northern Moamba district), reminisced about the power of tinhlanga to lay the groundwork of friendship between women with little in common besides gender and the accidental geography of marriage. Here too, the river was a crucial site for fostering such connections, but, as Melina suggests, so were the other gendered spaces where fellow women ordinarily encountered one another: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melina stressed that the possession of identical tattoos—whether by coincidence or design—made one woman the munghanu (friend) of another but also something more. Such women would henceforth refer to one another as chomi, a specifically feminine term of endearment. | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Looking each other over," however, could also be a competitive or even hostile process, especially in circumstances where differences constructed around class, marital status, or ethnicity gave rise to tensions among girls or women. The flip side of longing to be as beautiful as one's fellows was that peer pressure, usually expressed as name-calling, could drive a girl or woman to the mutlhaveli even when friendship was not at stake. Most women described peer mockery whereby untattooed female bodies were compared to fish (echoing Earthy's informants from the 1920s), a taunt they explained in terms of either the white color of a fish's belly or the smoothness of unmarked skin, which made a woman's body slippery and harder for a man to grasp. That tattooing was perceived as an important constituent of gender identity is implied even more directly in some women's recollection that they were called men (sing. nuna) until they had acquired tinhlanga. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yet here again, oral accounts make it clear that painfully inscribed standards of feminine beauty were targeted more at a female than male audience. The central feature of every interviewee's tinhlanga story was a graphic description of the suffering she had to endure throughout the tattooing process. In voices that ranged from melodramatic whisper to comic shriek, women narrated in great detail (and with uncannily evocative sound effects) how their skin was "stabbed" and "chopped," how their "blood ran everywhere," how they thought their "marhumbu [bowels] were coming out," how some girls had to be forcibly held down by their friends so that their squirming (or efforts to escape) would not spoil the scars. Olinda Ntimba explained that, because she was the first in her group to be tattooed, she "could not cry, because they'll laugh at you, your friends. When you're the first among them, all of them will stand and look at you when you're being cut. They'll watch you! They laugh at you, when you cry!" 47 Girls who sat through the process stoically were considered "strong" or "steady" (kutiya) and "courageous" (kutimisa); women who did so repeatedly bore permanent proof that they had no fear. Essential to these stories is a curious inversion of what scholars of southern Africa have claimed about local beliefs regarding the dangerous power of spilled female blood. In communities where menstrual blood allegedly endangers the health of men and cattle, where menstruating women are considered so "taboo" that they are denied not only sexual access to men but also physical contact with anything that might touch and so "pollute" them, 48 Magude interviewees took almost defiant pride in their willingness to shed non-menstrual blood in what they gleefully described as alarming quantities. The prominence of bloody imagery in women's oral narratives suggests its centrality to the meaning of tinhlanga, and invites a closer look at the gendered symbolism of blood (ngati) in this context. 49 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| According to Shangaan proverbs and stories, as well as ethnographic writings, non-menstrual blood possesses a number of contradictory powers. A metaphor for both the deepest obligations of kinship and the effort required to fulfill one's goals in life ("There is no tattoo without blood," that is, no achievement without struggle), blood is a positive force, a substance that guarantees personal well-being just as it heals illness, misfortune, or spirit possession when spilled through animal sacrifice or consumed as part of a ritual cure. Yet blood is also the most treacherous of the body's fluids: the loss of blood saps one's physical and moral strength (someone who is corrupt or cowardly is said to have "weak blood"); blood that has fallen on the ground must immediately be covered with sand because "wizards" might use it to make deadly "charms" (called tingati, the plural for blood); and life-sustaining liquids such as milk or beer can be made life-threatening by being magically transformed into blood. 50 With these apparently contrary meanings in mind, women's panegyrics about voluntary blood loss take on complex importance. Being tattooed means giving up one's blood and allowing it to fall freely on the ground, which makes one vulnerable to supernatural, physical, and social threats of all kinds. However, blood shed to obtain tinhlanga brings valuable rewards: new bonds of kinship (a kind of "blood sisterhood"); proof of nerve and bravery; and, ironically, a kind of dually re-gendered prestige, for if tattooing contributes to the making of girls into women, it does so in part by mimicking the battlefield heroics of men. In other words, the experience of being tattooed was just as crucial to its social and historical meaning for women as the tinhlanga themselves. At the heart of the experience was a test, a trial by ordeal, taken and judged within a circle of female peers, to demonstrate that feminine identity (in body and character) was not a quality a girl was born with but one she had to achieve, actively and bravely, on her own. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Experienced and performed together, the cutting ordeal could also cement affective ties among female peers across lines of economic, social, or cultural difference. On the day she finally decided to tell me about her own tattoos, Rosalina Malungana, the Swiss Mission-educated woman who, as we saw in chapter 3, reminisced so romantically about her common-law marriage to a Portuguese truck driver, acknowledged one source of conflict in their relationship that stemmed from Rosalina's desire to befriend her new non-Christian and nonliterate neighbors in Chibuto: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rosalina's representation of her motives for having herself tattooed—as, in her eyes, a married woman settling into life at her vukatini—is anything but straightforward. We cannot know with certainty, for example, to what extent her decision to be cut was voluntary and to what extent it was forced on her by friendly persuasion. We cannot know whether her motive was to win acceptance from her new female neighbors or to give her Portuguese husband a pleasant sexual surprise when he returned home. Probably her motives were mixed and her decision was neither purely voluntary nor forced. In that sense Rosalina's account is typical, as it emphasizes the multiple pressures and longings women articulated when remembering their decision to be tattooed. One thing that is clear from the above passage, though, is that Rosalina's tinhlanga narrative starts very deliberately from her riverside encounter with Mafasse and Muziosse, and it is their ambiguous commentary on her "belly"—its strange "white"-ness is what makes it beautiful for tattooing—that, in her memory, prompts her to accept Muziosse's offer. Rosalina was one of only two interviewees who identified whiteness—having the "belly of a mulungu"—as the taunt that spurred her to be cut, and in Rosalina's case her status as the nsati (wife) of a Portuguese man probably lent the women's teasing an additional racial cast. Rosalina herself gave no indication that tensions related to her interracial "marriage" played a role in the incident, highlighting as the principal factor in her decision her desire to be beautiful—in the eyes of her new female friends as much as in those of Agosto. Rosalina's representation of her motives for having herself tattooed—as, in her eyes, a married woman settling into life at her vukatini—is anything but straightforward. We cannot know with certainty, for example, to what extent her decision to be cut was voluntary and to what extent it was forced on her by friendly persuasion. We cannot know whether her motive was to win acceptance from her new female neighbors or to give her Portuguese husband a pleasant sexual surprise when he returned home. Probably her motives were mixed and her decision was neither purely voluntary nor forced. In that sense Rosalina's account is typical, as it emphasizes the multiple pressures and longings women articulated when remembering their decision to be tattooed. One thing that is clear from the above passage, though, is that Rosalina's tinhlanga narrative starts very deliberately from her riverside encounter with Mafasse and Muziosse, and it is their ambiguous commentary on her "belly"—its strange "white"-ness is what makes it beautiful for tattooing—that, in her memory, prompts her to accept Muziosse's offer. Rosalina was one of only two interviewees who identified whiteness—having the "belly of a mulungu"—as the taunt that spurred her to be cut, and in Rosalina's case her status as the nsati (wife) of a Portuguese man probably lent the women's teasing an additional racial cast. Rosalina herself gave no indication that tensions related to her interracial "marriage" played a role in the incident, highlighting as the principal factor in her decision her desire to be beautiful—in the eyes of her new female friends as much as in those of Agosto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yet while women's narratives accentuate the intragenerational community fostered by tattooing, intergenerational tattoo linkages were not absent from or irrelevant to their accounts. Most interviewees stated firmly that their tinhlanga were somehow different from those of their mothers and grandmothers, but specific notions of tattooed beauty could sometimes transcend generational lines, in part because older vatlhaveli exercised some influence over tinhlanga fashions. Here too the critical variable in tattooing decisions seems consistently to have been common geographic place.Indeed, listening to women in postwar Magude recount tinhlanga stories, it was easy to get the impression that local feminine constructions of beauty have been infinitely impermeable and cavalierly unconcerned with differences of age, class, status, ethnicity, etc.—indeed, knowing no other bounds beyond gender and place. Rosalina, for instance, said that both her mother, Anina Tivane (Nguni, by clan), and one of her father's half-sisters, Tshamatiko Malungana, bore at least one of the same tattoos, the xinkwahlana— a design popular among women in that area in the 1920s and 1930s—that Muziosse cut for Rosalina in Chibuto. 56 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perhaps more surprising is the elision of ethnic differences in women's selection of tinhlanga designs. Lucia Ntumbo, also Nguni, had most of her tinhlanga done by the elder sister of her maternal grandmother, an Ndau woman named Qimidzi Mandlaze,  in whose household in Chaimite (southern Gaza province) Lucia spent most of her adolescence in the late 1920s and who cut tattoos for "lines of girls" from their predominantly Shangaan village. Qimidzi, according to Lucia, had a limited repertoire and always cut the same set of designs, some of which she bore on her own body but which were for the most part tinhlanga currently in fashion in Chaimite, and which Qimidzi had learned from other local vatlhaveli and had seen on women's bodies "at the river." According to Lucia, her own daughter also had tattoos, but "they're not the same, because she was born in Xitezeni [Phadjane] and she cut tinhlanga there." 57 in whose household in Chaimite (southern Gaza province) Lucia spent most of her adolescence in the late 1920s and who cut tattoos for "lines of girls" from their predominantly Shangaan village. Qimidzi, according to Lucia, had a limited repertoire and always cut the same set of designs, some of which she bore on her own body but which were for the most part tinhlanga currently in fashion in Chaimite, and which Qimidzi had learned from other local vatlhaveli and had seen on women's bodies "at the river." According to Lucia, her own daughter also had tattoos, but "they're not the same, because she was born in Xitezeni [Phadjane] and she cut tinhlanga there." 57 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

That tattooing was an expression of consciously created ties of female spatial identity is reflected in the geographic distribution of particular kinds of tinhlanga, such as the makandu, a pattern consisting of rows of triangles made from small, round, tightly clustered keloid scars. The four women in the group of interviewees who had this design all received it in western Magude, when they were either residing or visiting the area, and I did not find any women with makandu in the eastern part of the district. Rosalina portrayed tinhlanga fashion in even more broadly geographical terms when we began discussing keloid tattooing of women's lower abdomen and thighs: That tattooing was an expression of consciously created ties of female spatial identity is reflected in the geographic distribution of particular kinds of tinhlanga, such as the makandu, a pattern consisting of rows of triangles made from small, round, tightly clustered keloid scars. The four women in the group of interviewees who had this design all received it in western Magude, when they were either residing or visiting the area, and I did not find any women with makandu in the eastern part of the district. Rosalina portrayed tinhlanga fashion in even more broadly geographical terms when we began discussing keloid tattooing of women's lower abdomen and thighs: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What, though, do the tattoos themselves mean? Women usually rebuffed my efforts to press them about the nhlamuselo (meaning) of their tinhlanga, insisting as Maria Xivuri did: "I don't know, I don't know. I hear that my friends—seeing friends, fellow girls, they cut [tattoos]. Well, you go, you're cut too. What they mean, these [tattoos], I don't know, I don't know anything." 59 Even when women knew the specific names of their tattoos, they often could not tell me why different designs were labeled in particular ways. As Talita Ubisse explained, "Only that xikoxana who cut them knows these things." 60 On their own, women's oral accounts might highlight female agency in choosing, copying, and disseminating tattoo fashion, yet the collective story they tell is a rather conservative and cautious one, set in secret feminine locations and affective relationships and claiming modestly little in the way of broader historical importance. Indeed, as narrations of experience they sketch a social landscape of deceptively limited interest to historians—a tale of networks of female friendship but beyond that perhaps nothing more than another illustration of the harrowing lengths to which women have gone to make themselves pretty. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recent scholarship from elsewhere in Africa sheds light on the range of discursive practices through which African bodies were remade, schooled, disciplined, commoditized, and dressed in the context of colonial power relations. Inspired by such social theorists as Gramsci, Foucault, Bourdieu, Merleau-Ponty, and more recently Judith Butler, much of this work has focused on the role of clothing in the (re)construction of colonial "social bodies"—the ways in which the corporeal bodies of African men and women have served as vehicles for the performance, appropriation, or resistance of colonial subjectivities through the clothes they wear. 61 As "signifier[s] of the social," dressed African bodies have been viewed as intrinsically political texts, embedded in yet also constitutive of hierarchies of racialized and gendered imperial power. 62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A conspicuous absence in this literature, with its emphasis on the contingent and "unstable surface" quality of the colonized body politic, is discussion of the cultural construction of African bodies unclothed—above all, the more permanent, indelible signs of social personhood that may be worn on the skin. 63 Scholarly and popular writings on body-marking in other contexts advance the metaphors of canvas, envelope, surface, or screen to convey the relationship between skin as medium and skin as message, yet these metaphors are all premised, as Frances Mascia-Lees and Patricia Sharpe have pointed out, on a patently Western vision of the body as unitary and distinct, a preconstituted "ground onto which patterns of signification can be inscribed." 64 In this work, the irreversibility of tattoos is seen to lend them special meaning as historical records of identity and events, mnemonic symbols registering everything from group membership and personal achievement to social misconduct and stigmatized status. Scholars' belief in the unique capacity of tattoos to communicate social personhood among dominated or marginal groups has inspired the study of tattoos in settings as diverse as the criminal underworld of nineteenth-century Germany, the marriage preparations of Moroccan women, and aboriginal communities in postcolonial North America. 65 Here, oddly enough, the political position of their bearers seems to dissuade commentators from scrutinizing body-markings as text. The possibility that permanent alterations of the body's surface might represent more profoundly challenging claims about the constitution of self and society than do practices involving temporary forms of body alteration remains largely unexplored, especially in African historical scholarship. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In this section, I examine changes in female tattooing practice in the Magude area over time and argue that, while women may explain the meanings of tinhlanga solely in terms of beauty and friendship, the immutable marks with which they have embellished their skin tell a rather more complicated story. Definite historical patterns emerged when I compared the temporal and spatial distribution of tinhlanga styles among interviewees. On the one hand, certain kinds of tinhlanga showed a definite trajectory of decline. Keloid facial scars seem to have disappeared by the 1920s; a few of the oldest women recalled their mother or grandmothers wearing such scars, but no one in the group had them or remembers seeing them on any of her peers. Keloid scarification of women's shoulders and backs, mainly in the makandu design mentioned above, became increasingly less common after the 1930s, as did the most extreme form of cicatrization on the lower abdomen and pubic area, which in some cases produced scars over half an inch in diameter. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

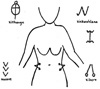

| Keloid tattoos—whose cutting women narrated in especially dramatic and gory detail—were made by lifting the skin with a ndzovo (fishhook), xikaya thorn, fingers, or safety pin and then slicing it (sometimes two or three times, to create a flap) with a razor blade or piece of broken glass. Ground charcoal or ash was mixed with nhlampfurha (castor oil) or tsumane (red ocher) and then rubbed into the wounds to darken the scars. 66 A variation of the dorsal tattoo was recorded by one of the ARPAC survey teams in 1981, on a 48-year-old woman who had her tinhlanga cut in the mid-1940s. Xikhoma nkata (clutch/hold your darling), the name this woman gave to her then unusual tattoo (because it was for "your husband to caress" during sexual intercourse), makes one meaning of this design quite explicit. 67 Hypogastric keloid tattoos, known as vusankusi, typically took the form of horizontal rows of decreasing numbers of round scars extending down from the navel, sometimes as far as the vagina itself. This type of tattoo was much more common among interviewees than was the makandu and was described by some Magude women as the most important tinhlanga of all. As Talita Ubisse explained (between hoots and gasps of tearful laughter), "Oh, your husband, he grabs and grabs, he feels happiness!" 68 No one among the women I interviewed had received vusankusi after the mid-1950s. | 50 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The type of tattoo that shows the greatest constancy over time during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries is the incised scarification of women's epigastric area or khwirhi (belly)—i.e., the front of a woman's torso between her breasts and her navel. All interviewees bore some version of the nxurhana (a geometric design consisting mostly of parallelograms and triangles) and/or the xilova (sets of parallel vertical and oblique lines). Both types were produced by drawing the pattern on the skin (with charcoal, a matchhead, or a pin) and then making small cuts (again, with broken glass or a razor blade) along the lines.  These tattoos range from simple patterns, based on as few as four or five lines, to elaborate networks of geometric figures extending across the entire belly and wrapping around the torso on both sides. Because of the widespread occurrence of the nxurhana in eastern Gaza province in the 1920s, and because Chopi and Lenge women told her that it represented either the ntete grasshopper, the forelegs of a khongoloti (millipede), or a species of lizard, E. Dora Earthy concluded that this tattoo more than any other carried ancient "vestiges of totemism." 69 None of the women I interviewed, however, indicated that the nxurhana had any meaning beyond its exceptionally intricate beauty. These tattoos range from simple patterns, based on as few as four or five lines, to elaborate networks of geometric figures extending across the entire belly and wrapping around the torso on both sides. Because of the widespread occurrence of the nxurhana in eastern Gaza province in the 1920s, and because Chopi and Lenge women told her that it represented either the ntete grasshopper, the forelegs of a khongoloti (millipede), or a species of lizard, E. Dora Earthy concluded that this tattoo more than any other carried ancient "vestiges of totemism." 69 None of the women I interviewed, however, indicated that the nxurhana had any meaning beyond its exceptionally intricate beauty. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In addition to their nxurhana/xilova tattoos, many interviewees also had one or more smaller designs incised on their belly or sides, and these tinhlanga were much more diverse.  About one-quarter of the group, including women of various ages, social backgrounds, and places of origin, had a tattoo they called xinkwahlana—a type of lizard, like the pattern Muziosse did for Rosalina—which had been cut for them between 1920 and 1950. Lídia Chavango, a woman in her eighties who grew up and married in the remote border area of northern Mapulanguene, recalled that some girls had "flowers" (singular, xiluva) or mpon'wana, a species of shrub, tattooed onto their sides. 70 Two slightly younger women from Facazisse had a chevron pattern Earthy believed was an arrowhead or snake, and one of these also had a scar she identified as a ximusana (small wooden pestle). Several women between the ages of sixty and eighty-five who had grown up near one of southern Mozambique's colonial towns, on the other hand, bore a symbol they called xikero (scissors) on one or both sides, while Katarina Matuka, who was born circa 1910 and spent her childhood near the coastal heartland of the Gaza state, had on her side a tattoo representing the xitlhangu (oval shield) carried by Nguni warriors. About one-quarter of the group, including women of various ages, social backgrounds, and places of origin, had a tattoo they called xinkwahlana—a type of lizard, like the pattern Muziosse did for Rosalina—which had been cut for them between 1920 and 1950. Lídia Chavango, a woman in her eighties who grew up and married in the remote border area of northern Mapulanguene, recalled that some girls had "flowers" (singular, xiluva) or mpon'wana, a species of shrub, tattooed onto their sides. 70 Two slightly younger women from Facazisse had a chevron pattern Earthy believed was an arrowhead or snake, and one of these also had a scar she identified as a ximusana (small wooden pestle). Several women between the ages of sixty and eighty-five who had grown up near one of southern Mozambique's colonial towns, on the other hand, bore a symbol they called xikero (scissors) on one or both sides, while Katarina Matuka, who was born circa 1910 and spent her childhood near the coastal heartland of the Gaza state, had on her side a tattoo representing the xitlhangu (oval shield) carried by Nguni warriors. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Between the 1920s and the 1940s, the exact date depending on the area, a dramatic shift occurred in tattooing practice: the introduction of a new method of producing scars using bunches of needles instead of sharp-edged cutting tools. While interviewees described this process with the verb kutlhavela, and recalled that nsiti (soot, ashes—i.e., ground charcoal) still served as coloring agents, needle-tattooing differs in several critical ways from keloid or incised scarification. Less painful, less bloody, and less likely to lead to infection, needle-tattooing also produces much less tactile—and more narrowly visual—transformations of the skin, and seems to have had no overtly sexual implication; at least, no interviewee mentioned male sexual interest when talking about these tinhlanga. This revolution in tattoo technology also led to important changes not only in tinhlanga aesthetics but in the social relations of female body-marking.  Women remember that, by the mid-1920s near Magude town, and by the mid-1930s further out in the countryside, younger and younger girls—even "children" (singular, mutsongwana)—were using needles and ash to give one another a new style of facial tattoo called swibayana, which consisted of clusters of round scars on the cheeks, forehead, and chin. Women who grew up in the environs of the Antioka mission station, including Valentina Chauke and Aldina Masangu, recall a fleeting yet popular tattooing fad among young girls throughout Facazisse and Makuvulane in the 1920s: Women remember that, by the mid-1920s near Magude town, and by the mid-1930s further out in the countryside, younger and younger girls—even "children" (singular, mutsongwana)—were using needles and ash to give one another a new style of facial tattoo called swibayana, which consisted of clusters of round scars on the cheeks, forehead, and chin. Women who grew up in the environs of the Antioka mission station, including Valentina Chauke and Aldina Masangu, recall a fleeting yet popular tattooing fad among young girls throughout Facazisse and Makuvulane in the 1920s:  having one's European first name written on the right forearm and one's clan name (or perhaps the name of "the boy you loved") written on the left. 71 In the hands of older girls and women, needles were employed to create patterns that were more complex and intended to represent objects from the agrarian landscape. Amélia Marikele and Katarina Matuka, for instance, each had needle-cut depictions of the traditional xikomu (iron hoe) tattooed onto their cheekbones by a woman friend circa 1940. having one's European first name written on the right forearm and one's clan name (or perhaps the name of "the boy you loved") written on the left. 71 In the hands of older girls and women, needles were employed to create patterns that were more complex and intended to represent objects from the agrarian landscape. Amélia Marikele and Katarina Matuka, for instance, each had needle-cut depictions of the traditional xikomu (iron hoe) tattooed onto their cheekbones by a woman friend circa 1940. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By the 1940s, needle-tattooing had encouraged a much more radical departure in women's body-marking, especially in the villages ringing Magude town. Older girls and women began to acquire needle-cut tinhlanga on their chest, arms, and thighs. These designs were not only substantially more ornate than previous ones. They also consisted entirely of images representing objects of European origin, incorporated new xilungu materials (ink and shoe polish, for example) as coloring agents, and in almost every case were tattooed onto women by men. Migrant workers returned home from South Africa or Swaziland with notebooks full of tinhlanga styles popular among women in their place of employment. By the 1940s, needle-tattooing had encouraged a much more radical departure in women's body-marking, especially in the villages ringing Magude town. Older girls and women began to acquire needle-cut tinhlanga on their chest, arms, and thighs. These designs were not only substantially more ornate than previous ones. They also consisted entirely of images representing objects of European origin, incorporated new xilungu materials (ink and shoe polish, for example) as coloring agents, and in almost every case were tattooed onto women by men. Migrant workers returned home from South Africa or Swaziland with notebooks full of tinhlanga styles popular among women in their place of employment.  These men offered their services to female kin and neighbors whose memories of this event stress the excitement of choosing, on the basis of what they understood "the girls had over there," from a wealth of new tattoo possibilities. 72 The most common male-cut tattoos among interviewees incorporated images of flowerpots, beveled diamonds and stars, and a crosslike design representing the trademark of the Blue Cross brand of condensed milk. Occasionally, the mutlhaveli would also include signs of his own xilungu identity: the name he used for work and tax purposes, and sometimes the year the tattoo was made. When I asked Albertina Tiwana whether a woman might encounter problems if she allowed a man who was not her husband to handle her body this way, her response was a phlegmatic "Mm-mm. We hear that those girls in Swaziland, they weren't afraid to bathe [in the river] with boys, so we weren't afraid [to show our legs to men] either." 73 These men offered their services to female kin and neighbors whose memories of this event stress the excitement of choosing, on the basis of what they understood "the girls had over there," from a wealth of new tattoo possibilities. 72 The most common male-cut tattoos among interviewees incorporated images of flowerpots, beveled diamonds and stars, and a crosslike design representing the trademark of the Blue Cross brand of condensed milk. Occasionally, the mutlhaveli would also include signs of his own xilungu identity: the name he used for work and tax purposes, and sometimes the year the tattoo was made. When I asked Albertina Tiwana whether a woman might encounter problems if she allowed a man who was not her husband to handle her body this way, her response was a phlegmatic "Mm-mm. We hear that those girls in Swaziland, they weren't afraid to bathe [in the river] with boys, so we weren't afraid [to show our legs to men] either." 73 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| To interpret these transformations in tattooing practice, we need to look at the social context in which tinhlanga styles waxed and waned and also at the changing social complexion of the tattooed population. At the same time as girls and women were inventing new methods and types of body-marking, they were also confronting new, sometimes violent pressures to cease decorating their bodies altogether. Lise Nsumbane, for example, was born circa 1910 less than three miles from the Swiss Mission station at Antioka and grew up in the household of her paternal aunt across the Nkomati River in Makuvulane. At the Swiss-run Makuvulane mission school, she remembers, | 55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juliana Kwinika, born in 1914 outside Caniçado (Guijá) but orphaned as a child and raised by the Catholic São Jerónimo mission in Magude town, offered a similar explanation when I asked her why, unlike her friends, she went only once to the elderly woman who cut her tattoos: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Like Lise Nsumbane, Valentina Chauke spent her childhood in Makuvulane but grew up in the lap of the mission community, in the homestead of her uncle Jakovo Chauke, a muvangeli (evangelist) for the Swiss, and next to the nhlarhu tree where worship services and classes were held. Valentina informed us that tattooing was not only "the work of heathens" but also a xidyoho (sin) and that it would "finish [i.e., use up] your blood." 76 Church girls caught with tinhlanga, she and other women recalled, risked being reprimanded, publicly shamed, and sometimes beaten by male or female European mission personnel or by male African evangelists, layworkers, and teachers. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Faced with the threat of corporal punishment and humiliation before vakriste (Christians), some girls decided that tattooing their body was not worth the risk, particularly when their marriage sights were set on a boy in the church. Tercina and Talita Ntimane, sisters from a coastal village in ka Ntimane (Manhiça) who married prominent church men in Facazisse and Makuvulane (respectively) in the early 1950s, seemed surprised when I asked them whether they had ever cut tinhlanga. Daughters of Swiss Mission converts whose homestead included the "heathen" wife of the girls' uncle, they never doubted that tattooing was forbidden, and they were afraid even to ask their uncle's wife about her abundant tinhlanga. 77 | 60 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christian censure, though, was not the only reason some girls and women began to turn away from body-marking in the mid to late colonial period. Sara Juma, a mestiça spirit medium born in 1942 to an Indo-African father and his local wife in Magude town, identified her "race" as Muslim, and had the following to say when I asked her about her way of life while she was growing up: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As we see in this passage, for Sara tinhlanga represented an affront not to her God but to her race, and body-marking functioned for her as the principal metonymic difference separating her from the embellished bodies of her "black" mother and sisters. Sara attributes her view of tinhlanga to her mother, who grew up on the grounds of the São Jerónimo mission station around the same time that Juliana Kwinika was attending school there. Sara's mother's desire to instill non-Shangaan values in her mixed-race daughter—and to define Sara as xilungu,a status she was not entitled to in colonial law—was certainly reinforced by Sara's own participation in the Catholic primary school in the late 1940s. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indeed, according to women's oral accounts, by the 1940s the place of female tattooing in mission Christianity's definitions of sin and heathenism had fully converged with Portuguese colonial discourses vaunting the benefits of assimilation while articulating the boundaries between colonizer and colonized, "civilized" and "native," in increasingly racialized terms. 79 In the aftermath of the 1928 Indigenato labor code—a bundle of laws designed to maximize state control over African labor by formalizing the distinction between (white) "citizens" and (nonwhite) "subjects"—assimilado status was regarded by most Africans, according to historian Jeanne Penvenne, as "the best of a bad deal." 80 Available only to Africans who were literate in Portuguese, had traded "tribal" for European culture, and were engaged in the colonial economy as artisans, traders, or skilled workers, assimilation promised all the rights enjoyed by Portuguese citizens, including exemption from forced labor. While these opportunities were meaningless for the vast majority of Africans (by 1961, less than 1 percent was legally assimilated 81), it appears that the shadow of this legislation had fallen on Magude by mid-century, so that "white" was a condition to aspire to and "black" one to be discarded or despised. Thus for many interviewees who had had contact with mission schools in their youth, tinhlanga embodied all that "civilized" women were supposed to abandon. Whether for God or the myth of attainable whiteness, black female skins were to remain smooth and unmarked. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This ideology helps to explain what seemed to me the odd reaction of Olinda Ntimba when she, Pastor Mbanza's wife, and I sat down together for our first interview. 82 Before I had even switched on the tape recorder, Olinda (who was born circa 1920 in Chobela,  just east of Facazisse) began to apologize that because she had been "formed in the xilandin way" she was an "animal" who didn't "know anything"; and that, because her parents were "heathens," she did not "find xilungu"—by which, as later became clear, she meant specifically the church, and generically "civilization"—until she married a Christian man in Makuvulane. Although Olinda at first spoke matter-of-factly about her traditional childhood, she became visibly nervous when I asked her about tinhlanga, and only after repeated reassurances from the pastor's wife that it was permissible to share such information did Olinda begin to relax and talk calmly about her tattoos. At the end of the interview, Olinda admitted that she had been afraid to tell me about "those things of long ago," because "the church always says [they] should be forgotten, we should leave them, their time is passed." 83 just east of Facazisse) began to apologize that because she had been "formed in the xilandin way" she was an "animal" who didn't "know anything"; and that, because her parents were "heathens," she did not "find xilungu"—by which, as later became clear, she meant specifically the church, and generically "civilization"—until she married a Christian man in Makuvulane. Although Olinda at first spoke matter-of-factly about her traditional childhood, she became visibly nervous when I asked her about tinhlanga, and only after repeated reassurances from the pastor's wife that it was permissible to share such information did Olinda begin to relax and talk calmly about her tattoos. At the end of the interview, Olinda admitted that she had been afraid to tell me about "those things of long ago," because "the church always says [they] should be forgotten, we should leave them, their time is passed." 83 | 65 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yet even for women such as Olinda, the threat of a beating and the racial stigmatization of tattooing were rarely enough to dissuade them from having tinhlanga done. Despite mounting disincentives from not only church elders and schoolteachers but also the Banyan traders who vigorously promoted xilungu fashions from their shops, both in town and across the countryside, the majority of girls and women continued to beautify themselves with tattoos. Ironically, the very clothing that "civilization" required African schoolgirls and church girls to wear made it possible for them to conceal the tinhlanga that European dress was supposed to be replacing. As Lise Nsumbane reasoned, "They cut [tattoos], everyone. Even here, inside the church, all the girls cut [tattoos]. Because, even if they forbade these things, no one is going to undress your belly [to look for tattoos]." 84 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||